Is Romance Dead? Erich Korngold and the Romantic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Symposium Programme

Singing a Song in a Foreign Land a celebration of music by émigré composers Symposium 21-23 February 2014 and The Eranda Foundation Supported by the Culture Programme of the European Union Royal College of Music, London | www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong Follow the project on the RCM website: www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong Singing a Song in a Foreign Land: Symposium Schedule FRIDAY 21 FEBRUARY 10.00am Welcome by Colin Lawson, RCM Director Introduction by Norbert Meyn, project curator & Volker Ahmels, coordinator of the EU funded ESTHER project 10.30-11.30am Session 1. Chair: Norbert Meyn (RCM) Singing a Song in a Foreign Land: The cultural impact on Britain of the “Hitler Émigrés” Daniel Snowman (Institute of Historical Research, University of London) 11.30am Tea & Coffee 12.00-1.30pm Session 2. Chair: Amanda Glauert (RCM) From somebody to nobody overnight – Berthold Goldschmidt’s battle for recognition Bernard Keeffe The Shock of Exile: Hans Keller – the re-making of a Viennese musician Alison Garnham (King’s College, London) Keeping Memories Alive: The story of Anita Lasker-Wallfisch and Peter Wallfisch Volker Ahmels (Festival Verfemte Musik Schwerin) talks to Anita Lasker-Wallfisch 1.30pm Lunch 2.30-4.00pm Session 3. Chair: Daniel Snowman Xenophobia and protectionism: attitudes to the arrival of Austro-German refugee musicians in the UK during the 1930s Erik Levi (Royal Holloway) Elena Gerhardt (1883-1961) – the extraordinary emigration of the Lieder-singer from Leipzig Jutta Raab Hansen “Productive as I never was before”: Robert Kahn in England Steffen Fahl 4.00pm Tea & Coffee 4.30-5.30pm Session 4. -

Die Tote Stadt

Portrait Georges Rodenbach von Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer (1895). Die tote • Die Hauptpersonen Stadt • Paul – Marie – Marietta • Aufführungsgeschichte, Fotos • Fakten • Rodenbachs Roman und Drama • Genesis – Illustrationen – Bedeutung – Textauszug • Korngolds Oper • Korngolds Selbstzeugnis – Genesis – Handlung • Psychologie • Musik • Nähe zu Mahler – Gesangspartien – musikalisches Material – Instrumentation • Videobeispiele © Dr. Sabine Sonntag Hannover, 17. Juni 2011 DIE HAUPTPERSONEN Paul Die verstorbene Marie Die Tänzerin Marietta Die Hauptdarstellerin Brügge Die Hauptdarstellerin Brügge Une Ville Abandonnée von Fernand Khnopff (1904) AUFFÜHRNGSGESCHICHTE FOTOS Aufführungen Die tote Stadt • 1967: Wien • 1975: New York City Aufführungen Die tote Stadt • 5. Februar 1983, Deutsche Oper Berlin Götz Friedrich, Anmoderation der Sendung von Die tote Stadt, ARD Aufführungen Die tote Stadt • 1985: Wien • 1988: Düsseldorf • 1991: New York City • 1990: Niederl. Radio • 1993: Amsterdam • 1995: Ulm • 1996: Catania Aufführungen Die tote Stadt • 1997: Spoleto, Wiesbaden • 1998: Washington • 1999: Bremerhaven, Köln • 2000: Karlsruhe • 2001: Straßburg • 2002: Bremen, Gera • 2003: Braunschweig, Zürich, Stockholm Aufführungen Die tote Stadt • 2004: Berlin, Salzburg • 2005: Osnabrück • 2006: Genf, Barcelona, New York City • 2007: Hagen • 2008: Bonn • 2009: Nürnberg, Venedig • 2010: Bern, Helsinki, Regensburg London 2009 Berlin, Deutsche Oper, 2004 Frankfurt 2011 Gelsenkirchen 2010 Madrid 2010 New York 1975 Nürnberg 2010 Palermo 1996 Regensburg 2011 San Francisco 2008 Helsinki 2010 Die Wiederentdeckung 1983 Berlin, Deutsche Oper 1983 FAKTEN • Text von Paul Schott alias Julius Korngold, Erich Wolfgang Korngolds Vater. • UA am 4. Dezember 1920 gleichzeitig im Stadttheater Hamburg (Dirigent: Egon Pollack) sowie im Stadttheater Köln (Dirigent: Otto Klemperer) • 1921 Wien, 1921 Met (Met-Debut von Maria Jeritza) • Das Libretto basiert auf dem symbolistischen Roman Das tote Brügge Bruges-la-morte, 1892; dt. -

Die Tote Stadt Op

Die tote Stadt op. 12 Oper in drei Bildern Frei nach Georges Rodenbachs Roman Bruges-la-morte von Paul Schott Musik von Erich Wolfgang Korngold pERSONEN Paul Tenor Marietta, Tänzerin Sopran Die Erschienung Mariens , pauls verstorbener Gattin } Frank, pauls Freund Bariton Brigitta, bei paul Alt Juliette, Tänzerin Sopran Lucienne, Tänzerin in Mezzosopran Gaston, Tänzer mariettas Mimikerrolle Victorin, der Regisseur Truppe Tenor Fritz, der pierrot } Bariton Graf Albert Tenor Beghinen, die Erscheinung der prozession, Tänzer und Tänzerinnen. Die handlung spielt in Brügge, Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts; die Vorgänge der Vision (II. und zum Teil III. Bild) sind mehrere Wochen später nach jenen des I. Bildes zu denken. La città morta op. 12 Opera in tre quadri Libero adattamento del romanzo Bruges-la-morte di Georges Rodenbach, di Paul Schott Traduzione italiana di Anna Maria Morazzoni (© 2009)* Musica di Erich Wolfgang Korngold pERSONAGGI Paul Tenore Marietta, ballerina Soprano L’apparizione di Marie , defunta moglie di paul } Frank, amico di paul Baritono Brigitta, governante di paul Contralto Juliette, ballerina Soprano Lucienne, ballerina della Mezzosoprano Gaston, ballerino compagnia Mimo Victorin, il regista di marietta Tenore Fritz, il pierrot } Baritono Il conte Albert Tenore Beghine, l’apparizione della processione, ballerini e ballerine. L’azione si svolge a Bruges, alla fine del secolo XIX; gli avvenimenti della visione (Quadro II e parte del III) vanno pensati diverse settimane dopo quelli del Quadro I. Prima rappresentazione assoluta: Amburgo, Stadttheater, 4 dicembre 1920 * per gentile concessione del Teatro La Fenice di Venezia. La traduzione tiene conto anche della versione di Laureto Rodoni ( www.scrivi.com ); alcune scelte lessicali sono desunte dalle varie versioni italiane del romanzo. -

Motion Picture Posters, 1924-1996 (Bulk 1952-1996)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt187034n6 No online items Finding Aid for the Collection of Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Processed Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Elizabeth Graney and Julie Graham. UCLA Library Special Collections Performing Arts Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Collection of 200 1 Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Descriptive Summary Title: Motion picture posters, Date (inclusive): 1924-1996 Date (bulk): (bulk 1952-1996) Collection number: 200 Extent: 58 map folders Abstract: Motion picture posters have been used to publicize movies almost since the beginning of the film industry. The collection consists of primarily American film posters for films produced by various studios including Columbia Pictures, 20th Century Fox, MGM, Paramount, Universal, United Artists, and Warner Brothers, among others. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections. -

Program Book

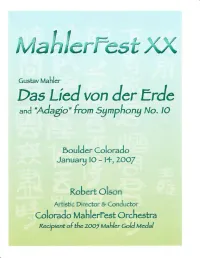

I e lson rti ic ire r & ndu r Schedule of Events CHAMBER CONCERTS Wednesday, January 1.O, 2007, 7100 PM Boulder Public Library Canyon Theater,9th & Canyon Friday, January L3, 7 3O PM Rocky Mountain Center for Musical Arts, 200 E. Baseline Rd., Lafayette Program: Songs on Chinese andJapanese Poems SYMPOSIUM Saturday, January L7, 2OO7 ATLAS Room 100, University of Colorado-Boulder 9:00 AM - 4:30 PM 9:00 AM: Robert Olson, MahlerFest Conductor & Artistic Director 10:00 AM: Evelyn Nikkels, Dutch Mahler Society 11:00 AMrJason Starr, Filmmaker, New York City Lunch 1:00 PM: Stephen E Heffiing, Case Western Reserve University, Keynote Speaker 2100 PM: Marilyn McCoy, Newburyport, MS 3:00 PMr Steven Bruns, University of Colorado-Boulder 4:00 PM: Chris Mohr, Denver, Colorado SYMPHONY CONCERTS Saturday, January L3' 2007 Sunday,Janaary L4,2O07 Macky Auditorium, CU Campus, Boulder Thomas Hampson, baritone Jon Garrison, tenor The Colorado MahlerFest Orchestra, Robert Olson, conductor See page 2 for details. Fundingfor MablerFest XXbas been Ttrouid'ed in ltartby grantsftom: The Boulder Arts Commission, an agency of the Boulder City Council The Scienrific and Culrural Facilities Discrict, Tier III, administered by the Boulder County Commissioners The Dietrich Foundation of Philadelphia The Boulder Library Foundation rh e va n u n dati o n "# I:I,:r# and many music lovers from the Boulder area and also from many states and countries [)AII-..]' CAMEI{\ il M ULIEN The ACADEMY Twent! Years and Still Going Strong It is almost impossible to fully comprehend -

Chronology 1916-1937 (Vienna Years)

Chronology 1916-1937 (Vienna Years) 8 Aug 1916 Der Freischütz; LL, Agathe; first regular (not guest) performance with Vienna Opera Wiedemann, Ottokar; Stehmann, Kuno; Kiurina, Aennchen; Moest, Caspar; Miller, Max; Gallos, Kilian; Reichmann (or Hugo Reichenberger??), cond., Vienna Opera 18 Aug 1916 Der Freischütz; LL, Agathe Wiedemann, Ottokar; Stehmann, Kuno; Kiurina, Aennchen; Moest, Caspar; Gallos, Kilian; Betetto, Hermit; Marian, Samiel; Reichwein, cond., Vienna Opera 25 Aug 1916 Die Meistersinger; LL, Eva Weidemann, Sachs; Moest, Pogner; Handtner, Beckmesser; Duhan, Kothner; Miller, Walther; Maikl, David; Kittel, Magdalena; Schalk, cond., Vienna Opera 28 Aug 1916 Der Evangelimann; LL, Martha Stehmann, Friedrich; Paalen, Magdalena; Hofbauer, Johannes; Erik Schmedes, Mathias; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 30 Aug 1916?? Tannhäuser: LL Elisabeth Schmedes, Tannhäuser; Hans Duhan, Wolfram; ??? cond. Vienna Opera 11 Sep 1916 Tales of Hoffmann; LL, Antonia/Giulietta Hessl, Olympia; Kittel, Niklaus; Hochheim, Hoffmann; Breuer, Cochenille et al; Fischer, Coppelius et al; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 16 Sep 1916 Carmen; LL, Micaëla Gutheil-Schoder, Carmen; Miller, Don José; Duhan, Escamillo; Tittel, cond., Vienna Opera 23 Sep 1916 Die Jüdin; LL, Recha Lindner, Sigismund; Maikl, Leopold; Elizza, Eudora; Zec, Cardinal Brogni; Miller, Eleazar; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 26 Sep 1916 Carmen; LL, Micaëla ???, Carmen; Piccaver, Don José; Fischer, Escamillo; Tittel, cond., Vienna Opera 4 Oct 1916 Strauss: Ariadne auf Naxos; Premiere -

Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Renaud Capuçon Violin Ravel

Program OnE HunDRED TwEnTi ETH SEASOn Chicago Symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music Director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor Emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, January 13, 2011, at 8:00 Friday, January 14, 2011, at 1:30 Saturday, January 15, 2011, at 8:00 Sunday, January 16, 2011, at 3:00 Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor renaud Capuçon Violin ravel Valses nobles et sentimentales Modéré Assez lent Modéré Assez animée Presque lent Assez vif Moins vif Epilogue (Lent) Korngold Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 35 Moderato nobile Romance: Andante Finale: Allegro assai vivace REnAuD CAPuçOn INtermISSIoN tchaikovsky Symphony no. 6 in B Minor, Op. 74 (Pathétique) Adagio—Allegro non troppo Allegro con grazia Allegro molto vivace Finale: Adagio lamentoso The appearance of Yannick Nézet-Séguin is endowed in part by the Nuveen Investments Emerging Artist Fund. Steinway is the official piano of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. 1 CommeNtS By PHiLLiP HuSCHER maurice ravel Born March 7, 1875, Ciboure, France. Died December 28, 1937, Paris, France. Valses nobles et sentimentales ranz Schubert was the first (He improvised waltzes throughout Fimportant composer to write the the wedding festivities of his dear word “waltz” on a score. By then— friend Leopold Kupelweiser, letting the early 1820s—waltzing had lived no one else near the piano; by a down its reputation as a scandalous fortuitous stroke of fate, one of the demonstration of excessive speed tunes remembered by the bride and and intimate physical contact on passed down through her family the dance floor. -

Wiederentdeckt. Der Komponist Berthold Goldschmidt

BERTHOLD GOLDSCHMIDT Geflohen - verstummt - wiederentdeckt. Der Komponist Berthold Goldschmidt GESPRÄCHSKONZERT DER REIHE MUSICA REANIMATA AM 22. NOVEMBER 2016 IN BERLIN BESTANDSVERZEICHNIS DER MEDIEN VON UND ÜBER BERTHOLD GOLDSCHMIDT IN DER ZENTRAL- UND LANDESBIBLIOTHEK BERLIN INHALTSANGABE KOMPOSITIONEN VON BERTHOLD GOLDSCHMIDT Noten Seite 3 Aufnahmen auf CD Seite 4 Aufnahmen in der Naxos Music Library Seite 6 SEKUNDÄRLITERATUR ÜBER BERTHOLD GOLDSCHMIDT Seite 7 LEGENDE Freihand Bestand im Lesesaal frei zugänglich Magazin Bestand für Leser nicht frei zugänglich, Bestellung möglich Außenmagazin Bestand außerhalb der Häuser, Bestellung möglich AGB Amerika-Gedenkbibliothek, Blücherplatz 1, 10961 Berlin – Kreuzberg Berlin-Studien im Haus BStB (Berliner Stadtbibliothek) BStB Berliner Stadtbibliothek, Breite Str. 30-36, 10178 Berlin – Mitte Naxos Music Library Streamingportal mit klassischer Musik –- sowohl an den Datenbank-PCs der ZLB als auch (mit Bibliotheksausweis) von zu Hause nutzbar 2 KOMPOSITIONEN VON BERTHOLD GOLDSCHMIDT NOTEN Mediterranean songs : for tenor and orchestra = Gesänge vom Mittelmeer / Berthold Goldschmidt. - London : Boosey & Hawkes, c 1996. - 83 Seiten. HPS 1294 Exemplare: Standort Außenmagazin AGB Signatur 008/000 009 519 (No 139 Golds 1) Passacaglia opus 4 for large orchestra / Berthold Goldschmidt. - London : Boosey & Hawkes, 1998. - 1 Studienpartitur (22 Seiten). - ISMN M-060-10791-7 Exemplare: Standort Magazin AGB Signatur 108/000 052 355 (No 147 Golds 1) String quartet no 2 : for string quartet [Noten] / Berthold Goldschmidt. - London : Boosey & Hawkes, [1991]. - 1 Partitur (42 Seiten) ; 31 cm. - Anmerkungen des Komponisten in Deutsch und Englisch Exemplare: Standort Freihand AGB Signatur No 190 Golds 2 String quartet no. 4 (1992) / Berthold Goldschmidt. - London [u.a.] : Boosey & Hawkes, 1994. - 20 Seiten Exemplare: Standort Magazin AGB Signatur No 190 Golds 1 [Sinfonien, Nr. -

Erich Wolfgang Korngold Tadt S Die Tote La Città Tadt

CopertaToPrint_std:v 14-01-2009 10:43 Pagina 1 1 La Fenice prima dell’Opera 2009 1 2009 Fondazione Stagione 2009 Teatro La Fenice di Venezia Lirica e Balletto Erich Wolfgang Korngold tadt S Die tote La città tadt ie tote ie tote S morta D orngold K olfgang W rich E FONDAZIONE TEATRO LA FENICE DI VENEZIA CopertaToPrint_std:v 14-01-2009 10:43 Pagina 2 foto © Michele Crosera Visite a Teatro Eventi Gestione Bookshop e merchandising Teatro La Fenice Gestione marchio Teatro La Fenice® Caffetteria Pubblicità Sponsorizzazioni Fund raising Per informazioni: Fest srl, Fenice Servizi Teatrali San Marco 4387, 30124 Venezia Tel: +39 041 786672 - Fax: +39 041 786677 [email protected] - www.festfenice.com FONDAZIONE AMICI DELLA FENICE STAGIONE 2009 Incontro con l’opera Teatro La Fenice - Sale Apollinee venerdì 16 gennaio 2009 ore 18.00 QUIRINO PRINCIPE Die tote Stadt Teatro La Fenice - Sale Apollinee venerdì 13 febbraio 2009 ore 18.00 LORENZO ARRUGA Roméo et Juliette Teatro La Fenice - Sale Apollinee venerdì 17 aprile 2009 ore 18.00 MASSIMO CONTIERO Maria Stuarda Teatro La Fenice - Sale Apollinee giovedì 14 maggio 2009 ore 18.00 LUCA MOSCA Madama Butterfly Teatro La Fenice - Sale Apollinee giovedì 18 giugno 2009 ore 18.00 GIORGIO PESTELLI Götterdämmerung Teatro La Fenice - Sale Apollinee mercoledì 2 settembre 2009 ore 18.00 GIANNI GARRERA Clavicembalo francese a due manuali copia dello La traviata strumento di Goermans-Taskin, costruito attorno alla metà del XVIII secolo (originale presso la Russell Teatro La Fenice - Sale Apollinee Collection di Edimburgo). lunedì 5 ottobre 2009 ore 18.00 Opera del M° cembalaro Luca Vismara di Seregno LORENZO BIANCONI (MI); ultimato nel gennaio 1998. -

Undiscovered Weill David Drew

Undiscovered Weill David Drew These two extracts from 'Kurt Weill: a Handbook' (published by Faber and Faber on September 28 at £25) have been specially adapted and in the second instance expanded by the author for serialization in OPERA, with the permission of the publishers. 1. Na Und? In March 1927 Weill completed the full score of a two-act opera provisionally entitled Na und? to a libretto by Felix Joachimson-Felix Jackson as he is known today. No libretto or scenario has survived. In a discussion with the present author in 1960, the librettist declared that he had only the haziest recollection of the plot. It concerned, he said, an Italian of humble birth who makes his fortune in America and then returns to his native village to find that his erstwhile fiancee is about to marry another. He abducts her to his mountain retreat, which is then besieged by the outraged villagers. Jackson was unable to recall the denouement or indeed any other details, except that he had based the libretto on a newspaper story. While that may seem to confirm the impression that Na und? was some sort of latterday verismo opera-a slice of Menotti before its time-surviving sections of the voice-and-piano draft (with barely legible text) give a very different impression. So too does the brief description provided by Weill himself, in a letter to his publishers (4 April 1927) enclosing a copy of the libretto: It is the first operatic attempt to throw light on the essence of our time from within, rather than by recourse to the obvious externals. -

COLORATURA and LYRIC COLORATURA SOPRANO

**MANY OF THESE SINGERS SPANNED MORE THAN ONE VOICE TYPE IN THEIR CAREERS!** COLORATURA and LYRIC COLORATURA SOPRANO: DRAMATIC SOPRANO: Joan Sutherland Maria Callas Birgit Nilsson Anna Moffo Kirstin Flagstad Lisette Oropesa Ghena Dimitrova Sumi Jo Hildegard Behrens Edita Gruberova Eva Marton Lucia Popp Lotte Lehmann Patrizia Ciofi Maria Nemeth Ruth Ann Swenson Rose Pauly Beverly Sills Helen Traubel Diana Damrau Jessye Norman LYRIC MEZZO: SOUBRETTE & LYRIC SOPRANO: Janet Baker Mirella Freni Cecilia Bartoli Renee Fleming Teresa Berganza Kiri te Kanawa Kathleen Ferrier Hei-Kyung Hong Elena Garanca Ileana Cotrubas Susan Graham Victoria de los Angeles Marilyn Horne Barbara Frittoli Risë Stevens Lisa della Casa Frederica Von Stade Teresa Stratas Tatiana Troyanos Elisabeth Schwarzkopf Carolyn Watkinson DRAMATIC MEZZO: SPINTO SOPRANO: Agnes Baltsa Anja Harteros Grace Bumbry Montserrat Caballe Christa Ludwig Maria Jeritza Giulietta Simionato Gabriela Tucci Shirley Verrett Renata Tebaldi Brigitte Fassbaender Violeta Urmana Rita Gorr Meta Seinemeyer Fiorenza Cossotto Leontyne Price Stephanie Blythe Zinka Milanov Ebe Stignani Rosa Ponselle Waltraud Meier Carol Neblett ** MANY SINGERS SPAN MORE THAN ONE CATEGORY IN THE COURSE OF A CAREER ** ROSSINI, MOZART TENOR: BARITONE: Fritz Wunderlich Piero Cappuccilli Luigi Alva Lawrence Tibbett Alfredo Kraus Ettore Bastianini Ferruccio Tagliavani Horst Günther Richard Croft Giuseppe Taddei Juan Diego Florez Tito Gobbi Lawrence Brownlee Simon Keenlyside Cesare Valletti Sesto Bruscantini Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau -

Opera Circle's Die Tote Stadt at the Ohio Theatre

Review: Opera Circle’s Die tote Stadt at the Ohio Theatre (June 14) by Daniel Hathaway Opera Circle staged an enticing production of Erich Korngold’s Die tote Stadt (“The Dead City”) on Saturday, June 14 at the Ohio Theatre in PlayHouseSquare. The opera is something of a rarity, probably because of the challenges of dealing with the eerie subtleties of its plot, its demand for a Heldentenor to sing the role of Paul, and its opulent 1920s orchestration. Die tote Stadt is a major undertaking for any small company, but Opera Circle admirably rose to the task. Though not flawless, the production succeeded in the most important operatic category: the music. A strong and dedicated cast of singers and generally fine playing from a 65- piece orchestra expertly led by Grigor Palikarov brought Korngold’s colorful and sometimes creepy music vividly to life. The opera, based on Georges Rodenbach’s 1892 novel, Bruges-la-Morte, and set in that Belgian canal town, explores the obsession of a widower (Paul) after the death of his wife (Marie). He sets up an altar in his house to enshrine her hair and other relics (the parallel to a vial of the blood of Christ preserved in the cathedral and processed through the streets once a year), but is unnerved when he meets Marietta, a dancer from Lille, and imagines her as a reincarnation of Marie. Marietta becomes the apex of a love triangle involving Paul and his friend Frank. The story hovers between reality and hallucination — complicated by an inexplicable second act encounter with a Pierrot troupe and a bizzare episode in which Paul believes he has strangled Marietta with Marie’s reliquated hair — finally resolving itself when Paul and Frank decide to turn their backs on this “City of Death.” The importance of the orchestra in Die tote Stadt was underlined in Opera Circle’s staging.