South Africa's Enduring Colonial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Low Countries. Jaargang 11

The Low Countries. Jaargang 11 bron The Low Countries. Jaargang 11. Stichting Ons Erfdeel, Rekkem 2003 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_low001200301_01/colofon.php © 2011 dbnl i.s.m. 10 Always the Same H2O Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands hovers above the water, with a little help from her subjects, during the floods in Gelderland, 1926. Photo courtesy of Spaarnestad Fotoarchief. Luigem (West Flanders), 28 September 1918. Photo by Antony / © SOFAM Belgium 2003. The Low Countries. Jaargang 11 11 Foreword ριστον μν δωρ - Water is best. (Pindar) Water. There's too much of it, or too little. It's too salty, or too sweet. It wells up from the ground, carves itself a way through the land, and then it's called a river or a stream. It descends from the heavens in a variety of forms - as dew or hail, to mention just the extremes. And then, of course, there is the all-encompassing water which we call the sea, and which reminds us of the beginning of all things. The English once labelled the Netherlands across the North Sea ‘this indigested vomit of the sea’. But the Dutch went to work on that vomit, systematically and stubbornly: ‘... their tireless hands manufactured this land, / drained it and trained it and planed it and planned’ (James Brockway). As God's subcontractors they gradually became experts in living apart together. Look carefully at the first photo. The water has struck again. We're talking 1926. Gelderland. The small, stocky woman visiting the stricken province is Queen Wilhelmina. Without turning a hair she allows herself to be carried over the waters. -

Universiteit Van Stellenbosch University Of

UNIVERSITEIT VAN STELLENBOSCH UNIVERSITY OF STELLENBOSCH NAVORSINGSVERSLAG RESEARCH REPORT 2003 Redakteur / Editor: PS Steyn Senior Direkteur: Navorsing / Senior Director: Research Universiteit van Stellenbosch / Stellenbosch University Matieland 7602 ISBN 0-7972-1083-0 i VOORWOORD Die Navorsingsverslag van 2003 bied 'n omvattende rekord van die navorsingsuitsette wat aan die Universiteit gelewer is. Benewens hierdie oorkoepelende verslag oor navorsing word jaar- liks ook ander perspektiewe op navorsing in fakulteitspublikasies aangebied. Statistieke om- trent navorsingsuitsette word in ander publikasies van die Universiteit se Afdeling Navorsings- ontwikkeling aangegee. Die Universiteit se navorsingspoging is, soos in die verlede, gesteun deur 'n verskeidenheid van persone en organisasies binne sowel as buite die Universiteit. Die US spreek sy besondere dank uit teenoor die statutêre navorsingsrade en kommissies, staatsdepartemente, sakeonder- nemings, stigtings en private indiwidue vir volgehoue ondersteuning in dié verband. Wat die befondsing van navorsing betref, word navorsers aan Suid-Afrikaanse universiteite – soos elders in die wêreld – toenemend afhanklik van nuwe bronne vir die finansiering van navorsing. Dit sluit beide nasionale en internasionale befondsingsgeleenthede in. Die Universi- teit van Stellenbosch heg daarom groot waarde aan streeksamewerking en aan betekenisvolle wetenskaplike ooreenkomste met ander universiteite in Suid-Afrika en in die buiteland, asook aan die bilaterale navorsings- en ontwikkelingsooreenkomste -

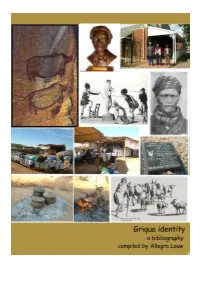

Griqua Identity – and Often As Equally Contested - Is the Matter of Terminology

INTRODUCTION Most scholars acknowledge that the origins of the Griqua people are rooted in the complex relationships between autochthonous KhoeSan, slaves, Africans and European settlers. Coupled with the intricacies that underpin the issue of Griqua identity – and often as equally contested - is the matter of terminology. Christopher Saunders and Nicholas Southey describe the Griquas as Pastoralists of Khoikhoi and mixed descent, initially known as Bastards or Basters, who left the Cape in the late 18th century under their first leader, Adam Kok 1 (c.1710- c.1795).1 They explain the name „bastards‟ as [The] term used in the 18th century for the offspring of mixed unions of whites with people of colour, most commonly Khoikhoi but also, less frequently, slaves.”2 Even in the context of post-apartheid South Africa, issues of identity and ethnicity continue to dominate the literature of the Griqua people. As the South African social anthropologist, Linda Waldman, writes: The Griqua comprise an extremely diverse category of South Africans. They are defined 3 neither by geographical boundaries nor by cultural practices. Waldman goes on to illustrate the complexities surrounding attempts to categorise the Griqua people by explaining how the Griqua have been described by some as a sub-category of the Coloured people,4 by others as either constituting a separate ethnic group,5 by others as not constituting a separate ethnic group6, and by still others as a nation.7 1 Christopher Saunders and Nicholas Southey, A dictionary of South African history. Cape Town: David Philip, 2001: 81-82. 2 Saunders and Southey, A dictionary of South African history: 22. -

The South African War As Humanitarian Crisis

International Review of the Red Cross (2015), 97 (900), 999–1028. The evolution of warfare doi:10.1017/S1816383116000394 The South African War as humanitarian crisis Elizabeth van Heyningen Dr Elizabeth van Heyningen is an Honorary Research Associate in the Department of Historical Studies at the University of Cape Town. Abstract Although the South African War was a colonial war, it aroused great interest abroad as a test of international morality. Both the Boer republics were signatories to the Geneva Convention of 1864, as was Britain, but the resources of these small countries were limited, for their populations were small and, before the discovery of gold in 1884, government revenues were trifling. It was some time before they could put even the most rudimentary organization in place. In Europe, public support from pro-Boers enabled National Red Cross Societies from such countries as the Netherlands, France, Germany, Russia and Belgium to send ambulances and medical aid to the Boers. The British military spurned such aid, but the tide of public opinion and the hospitals that the aid provided laid the foundations for similar voluntary aid in the First World War. Until the fall of Pretoria in June 1900, the war had taken the conventional course of pitched battles and sieges. Although the capitals of both the Boer republics had fallen to the British by June 1900, the Boer leaders decided to continue the conflict. The Boer military system, based on locally recruited, compulsory commando service, was ideally suited to guerrilla warfare, and it was another two years before the Boers finally surrendered. -

1 GJ Groenewald the Vicissitudes of the Griqua People in Nineteenth

‘FAMILY RELATIONS AND CIVIL RELATIONS:’ NICOLAAS WATERBOER’S JOURNAL OF HIS VISIT TO GRIQUALAND EAST, 1872 GJ Groenewald The vicissitudes of the Griqua people in nineteenth-century South Africa have been characterised variously as a ‘tragedy’ and an ‘injustice’.1 Although once a significant factor in the internal politics of the country, their history is little known in modern South Africa and rarely studied by historians. Because of their peregrinations, documents about them are scattered all over the country, often in the most unexpected places. In this article, a recent discovery of a hand-written journal by Nicolaas Waterboer, the last Griqua kaptyn (captain), is presented. Although historians have known that he visited Griqualand East shortly after its establishment, it is now possible to have a first-hand account by a sympathetic observer who intimately knew the people involved and their history. This is a rare opportunity to hear the voice of an African indigene describing the history of his own people and proffering his own motivations. The Rise of the Griqua Captaincies In the nineteenth century, the Griquas considered themselves the descendants of Adam Kok, later called ‘the First’ to distinguish him from his subsequent namesakes. Supposedly the son of a slave, he was farming as a free man in the Piketberg district by the 1750s.2 Kok assembled a following consisting of bastaard-hottentotten (the eighteenth-century nomenclature for the biracial offspring of Khoikhoi and Europeans) and the remains of the Chaguriqua, a Khoikhoi tribe whose ancestral land was in this area. The Dutch authorities at the Cape recognised Kok as a kaptyn (captain) and awarded him a staff of office. -

ESTORICA Szerelmey

--ESTORICA Szerelmey GordoQVsrhoof (6ol\raUSQ RESTORATION & RENOVATION London 735 8636 Johannesburg 614 6511 Cape Town 45 2302 Durban 211266 Pretoria 26 0555 Windhoek 2 5641 Redaksioneel Bewaring. Restourasie. Albei begrippe wat daagliks gehoor word. Begrippe wat 'n ou , (nuttelose?) gebou kan omskep in iets nuttigs, lewends en mooi. Maar nuttelose (!) begrippe as jy teen die ontwikkelaar (en soms die ower heid) te staan kom. Dan geld ander begrippe. Die soort met Van Riebeeck se kop op; die wat blink. En die tipe goed is gewoonlik skaars by al wat bewaarder is. Die probleem wat hier ter sprake is , is een wat gereeld ook deur die Stigting ondervind word. In dorpe en stede lui woonstel- of besigheidsregte op eiendomme dikwels die doodsklok vir menige statige gebou. 'n Mens kry soms die gevoel dat die stadsbeplanner sy strepe bloot op 'n kaart van die stad trek sonder om te beset dat 'n stad ook 'n le wende organisme is. Die kant kan bly, daardie kant moet weg. Soos Adam Small sou se : "Die dice het verkeerd geval vi ' ons. " Dit lyk asof die "dice" beslis verkeerd geval het vir die hoofstraat van Rustenburg , waar verkeersligte en vulstasies wedywer om aandag. Rustenburg se hoofstraat pas beslis nie meer by sy naam nie. Maar nou ja, vul stasies is darem handig vir die lang pad na Sun City. Maar dis nie net die Transvalers wat sondig nie. Om brandstof vir jou motor te kry, is ook in Worcester se hoofstraat nie moeilik nie. Die uithangborde wink so aanloklik dat 'n mens skoon van die prys van petrol vergeet. -

Bloemfontein Is a Pretty Little Place

Navorsinge VAN DIE NASIONALE MUSEUM BLOEMFONTEIN VOLUME 29, PART 3 DECEMBER 2013 The British soldiers' Bloemfontein: impressions and experiences during the time of the British occupation and Lord Roberts’ halt, 13 March – 3 May 1900 by Derek du Bruyn & André Wessels NAVORSINGE VAN DIE NASIONALE MUSEUM, BLOEMFONTEIN is an accredited journal which publishes original research results. Manuscripts on topics related to the approved research disciplines of the Museum, and/or those based on study collections of the Museum, and/or studies undertaken in the Free State, will be considered. Submission of a manuscript will be taken to imply that the material is original and that no similar paper is being or will be submitted for publication elsewhere. Authors will bear full responsibility for the factual content of their publications and opinions expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Museum. All contributions will be critically reviewed by at least two appropriate external referees. Contributions should be forwarded to: The Editor, Navorsinge, National Museum, P.O. Box 266, Bloemfontein, 9300, South Africa. Instructions to authors appear at the end of each volume or are available from the editor. --------------------------------------------------------------- NAVORSINGE VAN DIE NASIONALE MUSEUM, BLOEMFONTEIN is 'n geakkrediteerde joernaal wat oorspronklike navorsing publiseer. Manuskripte wat erkende studierigtings van die Museum omsluit en/of wat op die studieversamelings van die Museum gebaseer is en/of wat handel oor studies wat in die Vrystaat onderneem is, sal oorweeg word. Voorlegging van 'n manuskrip impliseer dat die materiaal oorspronklik is en geen soortgelyke manuskrip elders voorgelê is of voorgelê sal word nie. -

Principal's Corner

17-21 July 2017 PRINCIPAL’S CORNER The Free State Department of Sport, Arts, Culture and Recreation has welcomed Mandela Month which is dedicated in honor of our liberation stalwart and the first democratically elected President of South Africa Nelson Mandela. The Department encouraged the public to be strongly engaged in voluntary work and heroic deeds throughout our communi- ties on 18 July which is known as the Nelson Mandela International Day and commemorates the lifetime of service Nelson Mandela gave to South Africa and the world. This work should also continue during the whole month of July. Nelson Mandela stood for values such as non-racialism, non-sexism, and freedom for all. As a department, we continue to draw inspiration from the stories of ordinary Free Staters who display that indeed they are committed to realizing our vision for championing social transformation in society by using sport, arts, culture and recreation as their vehicle. This year’s Mandela Month is a reminder that South Africa is now a better place than what it was before 1994 and we owe it to leaders such as Former President Mandela and others to continue making South Africa and the Free State a better place to live in. Moving forward, we will continue to foster social cohesion and champion social transformation as a department. We will also continue to educate our youth about our country’s history, particularly, about those who fought for our freedom and democracy. Most importantly, we hold the responsibility to jealously guard the gains made by our democratic government since 1994 and create a better future for all our people. -

Evidence from the City of Bloemfontein, 1846-1946 Diaan Van Der Westhuizen

Colonial conceptions and space in the evolution of a city: evidence from the city of Bloemfontein, 1846-1946 Diaan van der Westhuizen Department of Architecture, University of the Free State, South Africa Email: [email protected] Mainstream understanding of how the urban form of South African cities developed over the past century and a half is often traced back to the colonial town plan. Writers argue that the gridiron and axial arrangement were the most important ordering devices. For example, in Bloemfontein—one of the smaller colonial capitals in South Africa— it has been suggested that the axial arrangement became an important device to anchor “the generalist structure of the gridiron within the landscape to create a specific sense of place”. Over the years, the intentional positioning of institutions contributed to a coherent legibility of the city structure in support of British, Dutch, and later apartheid government socio-political goals. During these eras, it was the colonial conceptions of space that influenced the morphological evolution of the city. This paper suggests that an alternative process guided the expansion of Bloemfontein. Drawing on the theory of natural movement, I suggest that Bloemfontein grew mainly as a result of its spatial configurational properties. Using longitudinal spatial mapping of the city from 1846 - 1946, empirical data from a Space Syntax analysis will be used to construct an argument for the primacy of space as a robust generator of development. The paper offers an alternative interpretation of the interaction between urban morphology and the process of place- making in a South African city. -

Jaargang 7, Nommer 2 – Augustus 2010

LitNet Akademies ’n Joernaal vir die Geesteswetenskappe Jaargang 7, nommer 2 – Augustus 2010 Hoofredakteur: Etienne van Heerden (PhD LLB), Hofmeyr Professor, Skool vir Tale en Letterkundes, Universiteit van Kaapstad Redakteur: Francis Galloway (DLitt) Redaksionele bestuurder: Naomi Bruwer (MA), Senior Inhoudsbestuurder by www.litnet.co.za Produksiebestuurder: Margaret Rossouw (MPhil) Taaladviseur: Nicky Grieshaber (MA) Tegniese span: Naomi Bruwer (MA), Senior Inhoudsbestuurder by www.litnet.co.za Margaret Rossouw (MPhil) Uitgewer: LitNet LitNet Akademies is ʼn geakkrediteerde akademiese aanlynjoernaal. Besoek: http://www.litnet.co.za/cgi-bin/giga.cgi?cat=201&limit=10&page- =0&sort=D&cause_id=1270&cmd=cause_dir_news E-pos: [email protected] Telefoonnommer: 021 886 5169 ISSN 1995-5928 Ondersteun deur: Inhoudsopgawe Tussen mans: ’n Perspektief op homososiale begeerte in Karel Schoeman se ’n Ander land Marius Crous - Skool vir Tale en Letterkunde, Nelson Mandela Metropolitaanse Universiteit 1 ’n Lang blik op Westerse moderniteit Johann Rossouw - Departement Politiek, Monash-universiteit, Melbourne, Australië 14 Die politiek van broederskap: Jacques Derrida, Jean-Luc Nancy en Jane Alexander se The Butcher Boys Jaco Barnard-Naudé - Departement Privaatreg, Universiteit van Kaapstad 23 Identifisering met die held en die emosionele betrokkenheid van kykers by rolprentdramas Francois Human - Departement Afrikaans, Universiteit van Pretoria 48 ’n Taalwet vir Suid-Afrika? Die rol van sosiolinguistiese beginsels by die ontleding van taalwetgewing -

Land, Sovereignty, and Indigeneity in South Africa

Notes Endnote Abbreviations CA Western Cape Archives and Records Services, Cape Town CRLR Commission on Restitution of Land Rights CWMA Council for World Mission Archive GM The Griqua Mission at Philippolis, 1822–1837 (Pretoria: Protea Book House, 2005), sources compiled by Karel Schoeman GR Griqua Records: The Philippolis Captaincy, 1825–1861 (Cape Town: Van Riebeeck Society, 1996), sources compiled by Karel Schoeman HCPP House of Commons Parliamentary Papers, Great Britain ODA Orania Dorpsraad Archives, Orania Introduction: Land, Sovereignty, and Indigeneity in South Africa 1. See, for instance, D. J. Jooste, Afrikaner Claims to Self-Determination: Reasons, Validity, and Feasibility (Pretoria: Technikon Pretoria/Freedom Front, 2002). My copy comes with a proud sticker on the cover testify- ing that it was ‘Gekoop in Orania’; the author and his wife formerly lived in the dorp. 2. ‘You can claim that something is yours until you are blue in the face’, relates property expert Carol Rose, ‘but unless others recognize your claims, it does you little good’. See Carol M. Rose, ‘Economic Claims and the Challenges of New Property’, in Katherine Verdery and Caroline Humphrey (eds), Property in Question: Value Transformation in the Global Economy (Oxford: Berg, 2004), p. 279. 3. See especially Carol M. Rose, Property and Persuasion: Essays on History, Theory and Rhetoric of Ownership (Boulder: Westview Press, 2004). 4. Robert C. Ellickson, ‘Property in Land’, Yale Law Journal 102 (1992–93), p. 1319. 5. See, for an introduction to some of these debates: Harold Demsetz, ‘Toward a Theory of Property Rights’, American Economic Review 57, 2 (1967), pp. 347–59; Richard A. -

Karel Schoeman En Die Leefwêreld Van Vroeë

G. van der Watt KAREL SCHOEMAN EN Dr. G. van der Watt, Navorsingsgenoot, Dept. Praktiese en DIE LEEFWÊRELD VAN Missionale Teologie, Universiteit van die VROEË SENDELINGE Vrystaat, Bloemfontein. E-pos:missio@ngkvs. IN SUID-AFRIKA – co.za ORCID: https://orcid. ’N OORSIG OOR org/0000-0002-5993- 636X SY SENDING- DOI: http://dx.doi. GESKIEDSKRYWING org/10.18820/23099089/ actat.Sup28.8 ISSN 1015-8758 (Print) ISSN 2309-9089 (Online) ABSTRACT Acta Theologica 2019 Karel Schoeman, the award-winning Afrikaans Suppl 28:121-145 author, not only wrote several seminal novels (for which he received the highest Afrikaans Date Published: literature prizes), but his contribution to research focusing on the 18th and early 19th century 6 December 2019 South African sociocultural history is also remarkable. He collected and put together an enormous volume of archival resources accessible to a large audience of interested readers and scholars alike. He especially concentrated on the history of missionaries and mission organisations; he wrote a long list of biographies, of which the most important ones were of women with some connection to the missionary endeavour. Schoeman’s unique approach to historiography is making a significant contribution that is relevant to missionary history and theology as such. He retrieved often neglected but important Published by the UFS voices from the past. Contrary to canonised, http://journals.ufs.ac.za/index.php/at confessional and denominational church history, © Creative Commons he opted to focus on missionaries (Black and With Attribution (CC-BY) White), slaves, women, and the historically marginalised. He wrote about their “lived faith” within the sociocultural contexts of their time.