Carrico Department of American Indian Studies, San Diego State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4 Tribal Nations of San Diego County This Chapter Presents an Overall Summary of the Tribal Nations of San Diego County and the Water Resources on Their Reservations

4 Tribal Nations of San Diego County This chapter presents an overall summary of the Tribal Nations of San Diego County and the water resources on their reservations. A brief description of each Tribe, along with a summary of available information on each Tribe’s water resources, is provided. The water management issues provided by the Tribe’s representatives at the San Diego IRWM outreach meetings are also presented. 4.1 Reservations San Diego County features the largest number of Tribes and Reservations of any county in the United States. There are 18 federally-recognized Tribal Nation Reservations and 17 Tribal Governments, because the Barona and Viejas Bands share joint-trust and administrative responsibility for the Capitan Grande Reservation. All of the Tribes within the San Diego IRWM Region are also recognized as California Native American Tribes. These Reservation lands, which are governed by Tribal Nations, total approximately 127,000 acres or 198 square miles. The locations of the Tribal Reservations are presented in Figure 4-1 and summarized in Table 4-1. Two additional Tribal Governments do not have federally recognized lands: 1) the San Luis Rey Band of Luiseño Indians (though the Band remains active in the San Diego region) and 2) the Mount Laguna Band of Luiseño Indians. Note that there may appear to be inconsistencies related to population sizes of tribes in Table 4-1. This is because not all Tribes may choose to participate in population surveys, or may identify with multiple heritages. 4.2 Cultural Groups Native Americans within the San Diego IRWM Region generally comprise four distinct cultural groups (Kumeyaay/Diegueno, Luiseño, Cahuilla, and Cupeño), which are from two distinct language families (Uto-Aztecan and Yuman-Cochimi). -

Understanding the Relationship Between Sedimentation, Vegetation and Topography in the Tijuana River Estuary, San Diego, CA

University of San Diego Digital USD Theses Theses and Dissertations Spring 5-25-2019 Understanding the relationship between sedimentation, vegetation and topography in the Tijuana River Estuary, San Diego, CA. Darbi Berry University of San Diego Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/theses Part of the Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, Geomorphology Commons, and the Sedimentology Commons Digital USD Citation Berry, Darbi, "Understanding the relationship between sedimentation, vegetation and topography in the Tijuana River Estuary, San Diego, CA." (2019). Theses. 37. https://digital.sandiego.edu/theses/37 This Thesis: Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF SAN DIEGO San Diego Understanding the relationship between sedimentation, vegetation and topography in the Tijuana River Estuary, San Diego, CA. A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Environmental and Ocean Sciences by Darbi R. Berry Thesis Committee Suzanne C. Walther, Ph.D., Chair Zhi-Yong Yin, Ph.D. Jeff Crooks, Ph.D. 2019 i Copyright 2019 Darbi R. Berry iii ACKNOWLEGDMENTS As with every important journey, this is one that was not completed without the support, encouragement and love from many other around me. First and foremost, I would like to thank my thesis chair, Dr. Suzanne Walther, for her dedication, insight and guidance throughout this process. Science does not always go as planned, and I am grateful for her leading an example for me to “roll with the punches” and still end up with a product and skillset I am proud of. -

Laguna and Laguna Meadow Grazing Allotments – Forest Environmental Assessment Service

United States Department of Agriculture Laguna and Laguna Meadow Grazing Allotments – Forest Environmental Assessment Service July 2010 Descanso Ranger District Cleveland National Forest San Diego County, California For Information Contact: Lance Criley 3348 Alpine Blvd. Alpine, CA 91901 (619) 445-6235 ext. 3457 The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Laguna and Laguna Meadow Grazing Allotments Environmental Assessment Descanso Ranger District, Cleveland National Forest, Page 1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Project Area Description The project area consists of the Laguna and Laguna Meadow grazing allotments on the Descanso Ranger District (Descanso RD) of the Cleveland National Forest (Cleveland NF). There are approximately 30,810 acres of National Forest System lands in the project area, which ranges in elevation from 3,200 to 6,200 feet. Legal locations of the allotments on the San Bernardino Base Meridian, San Diego County, are: Laguna Allotment: T15S, R5E, Sections 15 to 17, 20 to 29, 31 to 36; T15S, R6E, Section 31; T16S, R5E, Sections 1 to 24, and 26 to 35; T16S, R6E, Sections 6 to 8, 19; and T17S, R5E, Sections 1 to 5, 9 to 16, 21, and 22. -

Noteworthy Collection Mexico Anemone Tuberosa

NOTEWORTHY COLLECTION MEXICO ANEMONE TUBEROSA Rydb. (RANUNCULACEAE). — Baja California, Municipio of Ensenada, Ejido Nativos del Valle heading W to Santo Tomas, 31.42561°N, 116.34858°W (WGS 84), 434 m/1428 ft, 26 March 2010, Sula Vanderplank, Sean Lahmeyer, Ben Wilder and Karen Zimmerman 100326-29 (RSA), Less than 100 plants observed growing with Zigadenus sp. on N-facing side of a steep limestone outcrop. Most plants in full flower. Previous knowledge. The general habitat of this species is given by Dutton et al. (1997), in the Flora of North America, as from rocky slopes and stream sides 800-2500 m. It is known from desert regions of the southwestern USA (CA, NM, NV, TX, UT) and NW Mexico (Baja California, Sonora), and has been well documented within the Sonoran and Mojave deserts: Wiggins (1980) reports it from the western edge of the Colorado Desert and the eastern Mojave Desert; Wilken (1993) gives the range in California as eastern Desert Mountains; 900 – 1900 m; Munz (1974) reports elevations of 3000-5,000 ft (914-1520 m), in Joshua Tree Woodland and Pinyon-Juniper Woodland, western edge of the Colorado Desert, eastern Mojave Desert. The westernmost known collections for this taxon in California are from the southern Cuyamaca Mtns., near the southwestern end of Poser Mtn, March 19 1995, Jeri Hirshberg 253 (RSA) 60 km from the Pacific coast; and the Laguna Mountains, below Desert View, 06 April 1939, A. J. Stover 245 (SD), 80 km from the Pacific coast (CCH 2011). In Arizona, Kearney and Pebbles (1951) report elevations of 2,500-5000 ft (760-1520 m). -

Otay Mesa – Mesa De Otay Transportation Binational Corridor

Otay Mesa – Mesa de Otay Transportation Binational Corridor Early Action Plan Housing September 2006 Economic Development Environment TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Foundation of the Otay Mesa-Mesa de Otay Binational Corridor Strategic Plan..................................1 The Collaboration Process...........................................................................................................................1 The Strategic Planning Process and Early Actions .....................................................................................3 Organization of the Report ........................................................................................................................3 ISSUES FOR EVALUATION AND WORK PROGRAMS Introduction .................................................................................................................................................5 The Binational Study Area ..........................................................................................................................5 Issues Identified ...........................................................................................................................................5 Interactive Polling........................................................................................................................................7 Process.......................................................................................................................................................7 Results .......................................................................................................................................................8 -

Draft Vegetation Communities of San Diego County

DRAFT VEGETATION COMMUNITIES OF SAN DIEGO COUNTY Based on “Preliminary Descriptions of the Terrestrial Natural Communities of California” prepared by Robert F. Holland, Ph.D. for State of California, The Resources Agency, Department of Fish and Game (October 1986) Codes revised by Thomas Oberbauer (February 1996) Revised and expanded by Meghan Kelly (August 2006) Further revised and reorganized by Jeremy Buegge (March 2008) March 2008 Suggested citation: Oberbauer, Thomas, Meghan Kelly, and Jeremy Buegge. March 2008. Draft Vegetation Communities of San Diego County. Based on “Preliminary Descriptions of the Terrestrial Natural Communities of California”, Robert F. Holland, Ph.D., October 1986. March 2008 Draft Vegetation Communities of San Diego County Introduction San Diego’s vegetation communities owe their diversity to the wide range of soil and climatic conditions found in the County. The County encompasses desert, mountainous and coastal conditions over a wide range of elevation, precipitation and temperature changes. These conditions provide niches for endemic species and a wide range of vegetation communities. San Diego County is home to over 200 plant and animal species that are federally listed as rare, endangered, or threatened. The preservation of this diversity of species and habitats is important for the health of ecosystem functions, and their economic and intrinsic values. In order to effectively classify the wide variety of vegetation communities found here, the framework developed by Robert Holland in 1986 has been added to and customized for San Diego County. To supplement the original Holland Code, additions were made by Thomas Oberbauer in 1996 to account for unique habitats found in San Diego and to account for artificial habitat features (i.e., 10,000 series). -

INITIAL STUDY MITIGATED NEGATIVE DECLARATION April

FINAL INITIAL STUDY MITIGATED NEGATIVE DECLARATION TIJUANA ESTUARY SEDIMENT FATE AND TRANSPORT STUDY SCH Number: 2008011128 April 2008 State of California DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION Form A Notice of Completion & Environmental Document Transmittal Mail to: State Clearinghouse, P. O. Box 3044, Sacramento, CA 95812-3044 (916) 445-0613 SCH # 2008011128 For Hand Delivery/Street Address: 1400 Tenth Street, Sacramento, CA 95814 Tijuana Estuary Sediment Fate and Transport Study Project Title: Lead Agency: California Department of Parks and Recreation Contact Person: Christopher Peregrin Mailing Address: 301 Caspian Way Phone: (619) 575-3613 ext. 332 City: Imperial Beach Zip: 91932 County: San Diego Project Location: County: San Diego City/Nearest Community: Imperial Beach/San Diego Total Acres: 50-100 Cross Streets: Border Field State Beach between Monument Road and 2300' north of the horse trail road Zip Code: 91932 Assessor's Parcel No. Section: Twp. 19S Range: 2W Base: Within 2 Miles: State Hwy #: N/A Waterways: Pacific Ocean, Tijuana River Airports: N/A Railways: N/A Schools: N/A Document Type: CEQA: " NOP " Draft EIR NEPA: " NOI Other: " Joint Document " Early Cons " Supplement to EIR (Note prior SCH # below) " EA " Final Document " Neg Dec " Subsequent EIR (Note prior SCH # below) " Draft EIS " Other__________________ "✘ Mit Neg Dec " Other _________________________________ " FONSI Local Action Type: " General Plan Update " Specific Plan " Rezone " Annexation " General Plan Amendment " Master Plan " Prezone " Redevelopment " General Plan Element " Planned Unit Development " Use Permit "✘ Coastal Permit " Community Plan " Site Plan " Land Division (Subdivision, etc.) "✘ Other________________Scientific Study Development Type: " Residential: Units_______ Acres_______ " Water Facilities: Type___________________MGD_________ " Office: Sq.ft._______ Acres_______ Employees_______ " Transportation: Type__________________________________ " Commercial: Sq.ft. -

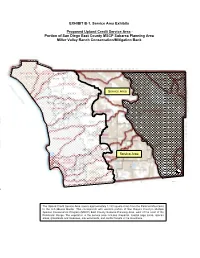

Service Area Maps

EXHIBIT B-1. Service Area Exhibits Proposed Upland Credit Service Area - Portion of San Diego East County MSCP Subarea Planning Area Miller Valley Ranch Conservation/Mitigation Bank CaD2 Service Area Service Area LcE2 The Upland Credit Service Area covers approximately 1,153 square miles from the Palomar Mountains to the U.S./Mexico Border. This corresponds with western portion of San Diego’s County’s Multiple Species Conservation Program (MSCP) EastAcG County Subarea Planning Area, west of the crest of the Peninsular Range. The vegetation in the service area includes chaparral, coastal sage scrub, riparian areas, grasslands and meadows, oak woodlands, and conifer forests in the mountains. Proposed Wetland Credit Service Areas - Miller Valley Ranch Conservation/Mitigation Bank Primary Service (Credit) Area: Upper Tijuana River Watershed Secondary Service (Credit) Area: Upper San Diego and Sweetwater Watershed The Wetland Service Areas extend from the northern limits of Ramona, then south through Alpine, Lakeside, Harbison Canyon, Jamul, and Dulzura to the Untied States/ Mexico Boarder. Wetland Credits are available for projects with impacted wetlands within the service area which are at or above the approximate 750-foot elevation level. The Primary Wetland Service Area, which consists of a portion of the upper watershed of the Tijuana River, covers approximately 500 square miles from the Laguna Mountains to the U.S./Mexico Border, where the Tijuana River enters Baja California Norte. Major tributaries in the Primary Service Area include Cottonwood Creek and Pine Creek. The vegetation in the service area ranges from chaparral to coastal sage scrub, with conifer forests in the mountains, riparian zones, and wetlands. -

Pine Valley 2019

2 | Page Pine Valley FSC CWPP 2019 3 | Page Pine Valley FSC CWPP 2019 Community Wildfire Protection Plans (CWPP) are blueprints for preparedness at the neighborhood level. They organize a community’s efforts to protect itself against wildfire, and empower citizens to move in a cohesive, common direction. Among the key goals of the Pine Valley Fire Safe Council CWPP, developed collaboratively by citizens, and federal, state, and local management agencies, are to: • Align with San Diego County Fire/CAL FIRE San Diego Unit’s cohesive pre-fire strategy, which includes educating homeowners and building understanding of wildland fire, ensuring defensible space clearing and structure hardening, safeguarding communities through fuels treatment, and protecting evacuation corridors • Identify and prioritize areas for hazardous fuel reduction treatment • Recommend the types and methods of treatment that will protect the community • Recommend measures to reduce the ignitability of structures throughout the area addressed by the plan. Note: The CWPP is not to be construed as indicative of project “activity” as defined under the “Community Guide to the California Environmental Quality Act, Chapter Three, Projects Subject to CEQA.” Any actual project activities undertaken that meet this definition of project activity and are undertaken by the CWPP participants or agencies listed shall meet with local, state, and federal environmental compliance requirements. 4 | Page Pine Valley FSC CWPP 2019 A. Overview Pine Valley is an alpine-like village that enjoys its proximity to mountains and forests. The area is appreciated as a recreational center for horseback riders, hikers, and bike riders. The Pine Valley Fire Safe Council (FSC) covers areas in and around Pine Valley, including Guatay, Corte Madera, and Buckman Springs. -

Master Special Use Permit Cleveland National Forest Orange and San Diego Counties, California Revised Plan of Development

SAN DIEGO GAS & ELECTRIC COMPANY MASTER SPECIAL USE PERMIT CLEVELAND NATIONAL FOREST ORANGE AND SAN DIEGO COUNTIES, CALIFORNIA REVISED PLAN OF DEVELOPMENT APRIL 2013 PREPARED BY: PREPARED FOR: Revised Plan of Development TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 – INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW OF PROPOSED ACTION ................................... 1 2 – PURPOSE AND NEED .......................................................................................................... 8 3 – ROUTE DESCRIPTION...................................................................................................... 11 3.0 69 kV Power Lines.......................................................................................................12 3.1 12 kV Distribution Lines .............................................................................................16 4 – PROJECT COMPONENTS ................................................................................................ 20 4.0 Facilities Included Under the MSUP ...........................................................................20 4.1 Wood-to-Steel Conversion ...........................................................................................20 4.2 Single- to Double-Circuit Conversion .........................................................................31 4.3 69 kV Power Line Undergrounding .............................................................................33 4.4 12 kV Distribution Line Undergrounding....................................................................34 4.5 Existing 12 -

Star Ranch | Offering Package

STAR RANCH | OFFERING PACKAGE All or Part of Up to ± 2,160 Acres of a Working Ranch with Potential Residential Subdivision for Up to 455 Lots Campo Area, San Diego County CalBRE #01225173 www.landadvisors.com STAR RANCH | CAMPO Table of Contents OFFERING SUMMARY Property Overview 4 Executive Summary 5 Location 6 Aerial Map 7 Vicinity Map 8 TTM #5459 9 Site Photos 10 Land Use Map 12 Soils Map 13 LOCAL OVERVIEW Local Overview 16 Regional Overview 17 Demographics 19 OFFERING GUIDELINES Offering Guidelines 21 CONFIDENTIALITY & DISCLAIMER Confidentiality & Disclaimer 23 Disclosure 24 Offering Package | 2 OFFERING SUMMARY | STAR RANCH STAR RANCH | CAMPO Property Overview PROPERTY HIGHLIGHTS Star Ranch (“Subject Property”) consists of ±2,160 gross acres of open space zoned as Semi-Rural Residential, in the Campo Area, San Diego County, California. The Subject Property is located within the community of Cameron Corners, Buckman Springs Roadand Highway 94, north of the United States and Mexico International Border. The immediate and long term potential for the Property is tremendous given: • Significant studies have been completed on the Star Ranch and a Draft EIR showing 455 residential lots could be ready for public review within 6 months. • Immediate access and visibility to Highway 94 as well as access to Interstate 8. • Access to job centers in San Diego County, Riverside County and Coachella Valley as well as the international border of Mexico and the United States. • Subject Property adjoins to the Cleveland National Forest. • Hour drive from Downtown San Diego. • Nearby Lake Morena Reservoir. STAR RANCH Offering Package | 4 STAR RANCH | CAMPO Executive Summary MUNICIPALITY OWNER OF RECORD Campo Area, San Diego County. -

Individual Biological Assessment Report

INDIVIDUAL BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT REPORT Site Name/Facility: Tijuana River Pilot Channel and Smuggler’s Gulch Channel 138a, 138b, 138c (Tijuana River Pilot Channel) and 138, 139 Master Program Map No.: (Smuggler’s Gulch Channel) Date: June 1, 2015 Biologist Name/Cell Phone No.: Vipul Joshi / 619.985.2149 Instructions: This form must be completed for each storm water facility identified in the Annual Maintenance Needs Assessment report and prior to commencing any maintenance activity on the facility. The Existing Conditions information shall be collected prior to preparing of the Individual Maintenance Plan (IMP) to assist in developing the IMP. The remaining sections shall be completed after the IMP has been prepared. Attach additional sheets as needed. EXISTING CONDITIONS The City of San Diego (City) has developed the Master Storm Water System Maintenance Program (MMP, Master Maintenance Program) (City of San Diego 2011a) to govern channel operation and maintenance activities in an efficient, economic, environmentally and aesthetically acceptable manner to provide flood control for the protection of life and property. This document provides a summary of the Individual Biological Assessment (IBA) components conducted within the Tijuana River Pilot (Pilot) Channel and the Smuggler’s Gulch (SG) Channel to comply with the MMP’s Programmatic Environmental Impact Report (PEIR) (City of San Diego 2011b). IBA procedures under the MMP provide the guidelines for an in-depth inspection of the proposed maintenance activity site including access routes, and temporary spoils storage and staging areas. A qualified biologist will determine whether or not sensitive biological resources could be affected by the proposed maintenance and potential ways to avoid impacts in accordance with the measures identified in the Mitigation, Monitoring and Reporting Program (MMRP) of the PEIR and the MMP protocols.