Morgan-Levy-2016-Cognition.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And I Heard 'Em Say: Listening to the Black Prophetic Cameron J

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pomona Senior Theses Pomona Student Scholarship 2015 And I Heard 'Em Say: Listening to the Black Prophetic Cameron J. Cook Pomona College Recommended Citation Cook, Cameron J., "And I Heard 'Em Say: Listening to the Black Prophetic" (2015). Pomona Senior Theses. Paper 138. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pomona_theses/138 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pomona Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pomona Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 And I Heard ‘Em Say: Listening to the Black Prophetic Cameron Cook Senior Thesis Class of 2015 Bachelor of Arts A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Bachelor of Arts degree in Religious Studies Pomona College Spring 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Chapter One: Introduction, Can You Hear It? Chapter Two: Nina Simone and the Prophetic Blues Chapter Three: Post-Racial Prophet: Kanye West and the Signs of Liberation Chapter Four: Conclusion, Are You Listening? Bibliography 3 Acknowledgments “In those days it was either live with music or die with noise, and we chose rather desperately to live.” Ralph Ellison, Shadow and Act There are too many people I’d like to thank and acknowledge in this section. I suppose I’ll jump right in. Thank you, Professor Darryl Smith, for being my Religious Studies guide and mentor during my time at Pomona. Your influence in my life is failed by words. Thank you, Professor John Seery, for never rebuking my theories, weird as they may be. -

THOUSAND MILE SONG Also by David Rothenberg

THOUSAND MILE SONG Also by David Rothenberg Is It Painful to Think? Hand’s End Sudden Music Blue Cliff Record Always the Mountains Why Birds Sing THOUSAND MILE SONG Whale Music In a Sea of Sound DAVID ROTHENBERG A Member of the Perseus Books Group New York Copyright © 2008 by David Rothenberg Published by Basic Books, A Member of the Perseus Books Group All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Basic Books, 387 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016–8810. Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 255–1514, or e-mail [email protected]. Designed by Linda Mark Set in 12 pt Granjon by The Perseus Books Group Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rothenberg, David, 1962- Thousand mile song: whale music in a sea of sound / David Rothenberg. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-465-07128-9 (alk. paper) 1. Whales—Behavior. 2. Whale sounds. I. Title. QL737.C4R63 2008 599.5’1594—dc22 2007048161 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS 1 WE DIDN’T KNOW, WE DIDN’T KNOW: Whale Song Hits the Charts 1 2GONNA GROW -

El Gato Negro Menu December 2018

PARA PICAR CHARCUTERIE Matrimonia: marinated and salted anchovies and piquillo pepper on tostada ..........6.5 Black truffle salchichón with cornichons ..........................................................................6 Padrón peppers with Halen Môn sea salt .........................................................................5 Ibérico chorizo with caperberries ..................................................................................5.5 Our own-recipe marinated olives with chilli, lemon, garlic and rosemary ..................4 Teruel lomo (sliced, cured pork loin) with celeriac rémoulade .....................................6 Roasted Valencia almonds..................................................................................................4 Jamón serrano with celeriac rémoulade 50g ....................................................................6 Catalan bread with olive oil, garlic and fresh tomato .....................................................4 Cecina (cured, smoked beef) with shaved Manchego and pickled walnuts ...............8 Catalan bread with olive oil, garlic, fresh tomato and jamón serrano .......................5.5 Acorn-fed jamón ibérico de bellota 50g ..........................................................................13 Sourdough bread with olive oil and Pedro Ximénez balsamic ...................................3.5 Picos Blue cheese with caramelized walnuts................................................................5.5 Bikini (toasted sandwich with jamón serrano, Manchego & -

New Order Ghost Gigs a Disruption 002

New Order Ghost Gigs A Disruption 002 ORIGINALLY RECORDED FRIDAY 6 DECEMBER 1985 1.15pm, Thursday 6 December 2018 The Hive, New Cavendish Street hursday 6 December marks the anniversary of SETLIST New Order playing at our New Cavendish Street site. It is in fact the 33rd anniversary, which seems appropriate given the musical relevance of 331/3 RPM. 1985 marked the midpoint of a curious and eclectic musical 1 decade. On one level the era of Phil Collins and Paul Young, of Band Aid ATMOSPHERE Tand Bryan Adams, of Stock Aitken & Waterman and Stars Stars on 45. However outside of this superficial view the period was an amazingly diverse one. The 2 beginning of the decade saw the end of the post punk and new wave period, the DREAMS NEVER END emergence of the much maligned new romantic scene and the critically acclaimed two tone movement. At the same time rap music began to enter the mainstream 3 and later came the House Sound of Chicago and stirrings from Detroit, the PROCESSION second summer of love and the high water mark of rave culture, with the end 4 of the decade seeing guitar music enter centre stage again through the rise of SUNRISE grunge. Seminal albums were released throughout that still stand the test of time. 5 For New Order 1985 was the year of Lowlife, LONESOME TONIGHT the Festival of the Tenth Summer. Formed in 1980 from the ashes of Joy Division after the 6 untimely death of Ian Curtis, New Order were WEIRDO a groundbreaking band. Signed to Factory Records, and very much the Factory band, the 7 group had by this point released three critically 586 acclaimed albums and a batch of unassailable 8 singles, including Ceremony (A Joy Division THE PERFECT KISS song, and the first New Order single neatly seguing past and future), Temptation (the 9 first dance infused glimpse of what was to FACE UP come) and the groundbreaking Blue Monday 10 (allegedly the best selling 12" single of the time, but which lost money due to the AGE OF CONSENT technical aesthetic requirements of its sleeve). -

Court-Ordered Law Breaking: U.S

Brooklyn Law Review Volume 81 | Issue 1 Article 5 2015 Court-Ordered Law Breaking: U.S. Courts Increasingly Order the Violation of Foreign Law Geoffrey Sant Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr Recommended Citation Geoffrey Sant, Court-Ordered Law Breaking: U.S. Courts Increasingly Order the Violation of Foreign Law, 81 Brook. L. Rev. (2015). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr/vol81/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Law Review by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. Court-Ordered Law Breaking U.S. COURTS INCREASINGLY ORDER THE VIOLATION OF FOREIGN LAW Geoffrey Sant† INTRODUCTION Perhaps the strangest legal phenomenon of the past decade is the extraordinary surge of U.S. courts ordering individuals and companies to violate foreign law.1 Indeed, until fairly recently, it was virtually unheard of for a U.S. court to order the violation of foreign laws.2 In 1987, a U.S. circuit court even stated, per curiam, that it was unsure “whether a court may ever order action in violation of foreign laws” and added “that it causes us considerable discomfort to think that a court of law should order a violation of law, particularly on the territory of the sovereign whose law is in question.”3 Over the past decade, however, the phenomenon of court-ordered law breakinG has increased at an exponential rate. Sixty percent of all instances of courts orderinG the violation of foreign laws have occurred in the last five years. -

Crazy Rich Asians

CRAZY RICH ASIANS Screenplay by Peter Chiarelli and Adele Lim based on the novel by Kevin Kwan This script is the confidential and proprietary property of Warner Bros. Pictures and no portion of it may be performed, distributed, reproduced, used, quoted or published without prior written permission. FINAL AS FILMED Release Date Biscuit Films Sdn Bhd - Malaysia August 15, 2018 Infinite Film Pte Ltd - Singapore © 2018 4000 Warner Boulevard WARNER BROS. ENT. Burbank, California 91522 All Rights Reserved OPENING TITLES MUSIC IN. SUPERIMPOSE: Let China sleep, for when she wakes, she will shake the world. - Napoleon Bonaparte FADE IN: EXT. CALTHORPE HOTEL - NIGHT (1995) (HEAVY RAIN AND THUNDER) SUPERIMPOSE: LONDON 1995 INT. CALTHORPE HOTEL - CLOSE ON A PORTRAIT - NIGHT of a modern ENGLISH LORD. The brass placard reads: “Lord Rupert Calthorpe-Cavendish-Gore.” REVEAL we’re in the lobby of an ostentatious hotel. It’s deserted except for TWO CLERKS at the front desk. It is the middle of the night and RAINING HEAVILY outside. ANGLE ON HOTEL ENTRANCE The revolving doors start to swing as TWO CHILDREN (NICK 8, ASTRID 8) and TWO CHINESE WOMEN, ELEANOR and FELICITY YOUNG (30s) enter. They’re DRIPPING WET, dragging their soaked luggage behind them. Nick SLIDES his feet around the polished floor, leaving a MUDDY CIRCLE in his wake. The clerks look horrified. Eleanor makes her way to the front desk, while complaining to Felicity about having to walk in the bad weather. ELEANOR (in Cantonese; subtitled) If you didn’t make us walk, we wouldn’t be soaked. Felicity grabs the children by the hand and follows Eleanor to the front desk. -

SEALED 4 S/ T

Case 3:21-mj-02060-JLB Document 1 Filed 05/21/21 PageID.68 Page 1 of 53 1 2 3 SEALED 4 s/ T. Ferris 5 6 7 ORDERED UNSEALED on 07/19/2021 s/ TrishaF 8 9 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 10 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 11 12 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Case No.: 21-MJ-2060 13 Plaintiff, COMPLAINT FOR VIOLATION OF: 14 v. Title 21 U.S.C.§ 841(a)(1) 15 Distribution of a Controlled Substance 16 Lindsay Renee HENNING, (Felony); Title 21 U.S.C. §§ 841(a)(1) 17 Garrett Carl TUGGLE, and 846 Conspiracy to Distribute LSD (Felony); Title 18, U.S.C., Sec. 1349 – 18 Defendants. Conspiracy; Title 18, U.S.C., Sec. 19 981(a)(1)(C), and Title 28, U.S.C., Sec 2461(c) – Criminal Forfeiture 20 21 22 23 The undersigned complainant being duly sworn states: 24 COUNT ONE 25 On or about June 15, 2020, within the Southern District of California, defendant, 26 Lindsay Renee HENNING, did knowingly and intentionally distribute approximately 7 27 grams (0.015 pounds) of a mixture and substance containing a detectable amount of 28 Case 3:21-mj-02060-JLB Document 1 Filed 05/21/21 PageID.69 Page 2 of 53 1 methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), a Schedule II Controlled Substance in 2 violation of Title 21, United States Code, Section 841(a)(1). 3 COUNT TWO 4 Beginning at a date unknown and continuing up to and including September 8, 2020, 5 within the Southern District of California, defendant, Lindsay Renee HENNING, did 6 knowingly and intentionally conspire together with JT and with other persons known and 7 unknown to distribute approximately 1 gram and more, of a mixture and substance 8 containing a detectable amount of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), a Schedule I 9 Controlled Substance; in violation of Title 21, United States Code, Sections 841(a)(1) and 10 846 and, Title 18, United States Code, Section 2. -

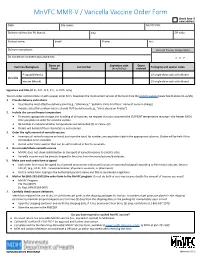

Mnvfc MMR-V / Varicella Vaccine Order Form Check Here If New Address Date: Site Name: Mnvfc PIN

MnVFC MMR-V / Varicella Vaccine Order Form Check here if new address Date: Site name: MnVFC PIN: Delivery address (no PO boxes): City: ZIP code: Contact name: Email: Phone: Fax: Delivery instructions: Current freezer temperature: Do not deliver on these days and times: C or F Vaccines/biologicals Doses on Lot number Expiration date Doses Packaging and special notes hand (mm/dd/yy) ordered Proquad (Merck) 10 single-dose vials with diluent Varicella Varivax (Merck) 10 single-dose vials with diluent Signature and title (M.D., D.O., N.P., P.A., or R.Ph. only) ________________________________________________________________________________ You can order vaccine online or with a paper order form. Download the most current version of the form from the MnVFC website (www.health.state.mn.us/vfc). 1. Provide delivery instructions ● Describe the most effective delivery point (e.g., "pharmacy," "pediatric clinic-2nd floor," name of nurse in charge). ● Indicate dates/times when vaccine should NOT be delivered (e.g., "clinic closed on Fridays"). 2. Include the current freezer temperature ● To ensure appropriate storage and handling of all vaccines, we request that you document the CURRENT temperature reading in the freezer EACH time you place an order for varicella vaccine. ● Remember to indicate whether temperatures are Fahrenheit (F) or Celsius (C). ● Orders will be held if this information is not included. 3. Order the right amount of varicella vaccine ● Inventory all varicella vaccine on hand, and note the total, lot number, and expiration date in the appropriate columns. Orders will be held if this information is not included. ● Do not order more vaccine than can be administered in four to six weeks. -

Roger-Scruton-Beauty

Beauty This page intentionally left blank Beauty ROGER SCRUTON 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Horsell’s Farm Enterprises Limited The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Italy and acid-free paper by Lego S.p.A ISBN 978–0–19–955952–7 13579108642 CONTENTS Picture Acknowledgements vii Preface ix 1. -

What Is the Liberal International Order?

Policy Essay | Liberal International Order Project | 2017 | No.17 What is the Liberal International Order? By Hans Kundnani In the last five years or so, U.S. and European foreign policy think tanks have become increasingly preoccupied with threats to the set of norms, rules, and institutions known as the liberal international order, especially from “revisionist” rising powers and above all authoritarian powers like China and Russia. But even more recently it has also become increasingly apparent that support for the liberal international order Although Western analysts and policymakers in Europe and the United States is declining as well. often to refer to the “liberal international order,” the This has become particularly clear since the British phrase is far from self-explanatory. In particular, it is vote to the leave the European Union last June and the not obvious in what sense the liberal international U.S. presidential election last November — not least order is “liberal.” The lack of precision about what is because the United Kingdom and the United States meant by the liberal international order is a problem are two of the countries historically most associated with liberalism and were generally thought to be most because it obscures the complexities of the concept committed to it. and inhibits self-criticism by Western policymakers, especially Atlanticists and “pro-Europeans” who seek However, although the phrase “liberal international to defend the liberal international order. order” is widely used, it is far from self-explanatory. The liberal international order has evolved Theorists of the liberal international order understand since its creation after World War II and has different it as an “open and rule-based international order” that is “enshrined in institutions such as the United elements — some of which are in tension with each Nations and norms such as multilateralism.”1 But this other. -

What Makes This Growth Unique Is That It Has Taken Place in a Cloud of Wonder and Kindness and Constant Kickstarts of the Soul

194 Nassau Street Suite 212 PACIFIC Princeton, NJ 08542 Phone: 609.258.3657 Email: [email protected] www.princeton.edu/~pia Newsletter of PrincetonBRIDGES in Asia Spring 2016 THE THAILAND ISSUE: Celebrating 40 years of Princeton in Asia Fellows in the Kingdom of Thailand VOICES FROM THE FIELD: Notes from our Fellows Personal growth has been the most special element of my time in Asia thus far. Deal- ing with the various challenges presented by opaque bureaucracy, occasional incom- petence (both my own and others’), endless layers of sweat, a bout of head lice, inde- scribable traffic, and the isolation inherent to living abroad has made me a more flex- ible and mature person. What makes this growth unique is that it has taken place in a cloud of wonder and kindness and constant kickstarts of the soul. I’m glad that the les- sons I’m learning right now are based not on an affirmation of the ideas I’ve held my entire life but rather a constant desta- bilization of these ideas: that my move- ment forward is contingent upon expand- ing my capacity for negative capability. Cheers to 40 years of PiA fellows in Thailand! Reflecting on her first year in Nan, 2nd year PiA Devin Choudhury fellow Brenna Cameron (Bandon Srisermkasikorn School ‘14-’16) wrote, “Nan makes me come Royal University of Phnom Penh alive and I can’t wait to return to the students who have become my children, coworkers who have Phnom Penh, Cambodia beome like family, and a country that now strangely feels like home.” all of us so different and all of us here be- The principal of my school gave a won- What makes this cause of different reasons, with different derful speech at our school’s graduation expectations, and having different daily re- ceremony. -

Jane Williams (Ysgafell) (1806-85) and Nineteenth-Century Welsh Identity

Gwyneth Tyson Roberts Department of English and Creative Writing Thesis title: Jane Williams (Ysgafell) (1806-85) and nineteenth-century Welsh identity SUMMARY This thesis examines the life and work of Jane Williams (Ysgafell) and her relation to nineteenth-century Welsh identity and Welsh culture. Williams's writing career spanned more than fifty years and she worked in a wide range of genres (poetry, history, biography, literary criticism, a critique of an official report on education in Wales, a memoir of childhood, and religious tracts). She lived in Wales for much of her life and drew on Welsh, and Welsh- language, sources for much of her published writing. Her body of work has hitherto received no detailed critical attention, however, and this thesis considers the ways in which her gender and the variety of genres in which she wrote (several of which were genres in which women rarely operated at that period) have contributed to the omission of her work from the field of Welsh Writing in English. The thesis argues that this critical neglect demonstrates the current limitations of this academic field. The thesis considers Williams's body of work by analysing the ways in which she positioned herself in relation to Wales, and therefore reconstructs her biography (current accounts of much of her life are inaccurate or misleading) in order to trace not only the general trajectory of this affective relation, but also to examine the variations and nuances of this relation in each of her published works. The study argues that the liminality of Jane Williams's position, in both her life and work, corresponds closely to many of the important features of the established canon of Welsh Writing in English.