Working Paper No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review of Research Impact Factor : 5.7631(Uif) Ugc Approved Journal No

Review Of ReseaRch impact factOR : 5.7631(Uif) UGc appROved JOURnal nO. 48514 issn: 2249-894X vOlUme - 8 | issUe - 3 | decembeR - 2018 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATION AGAINST WOMEN IN TAMILNADU – A SUBALTERN CRISIS Anil Kumar Meena CReNIEO , University of Madras. ABSTRACT Women are in subjugated position in various socio-political structures in Tamilnadu a state considered having radical society in culture and politics among Indian states. Inspite of the emancipations achieved through education and cultural renaissance happened in recent past, gender bias persists across the society among all stratified communities. The International commission for Women has categorized the violence’s against women into few types. Almost all the categories of violence’s are found prevalent in Tamilnadu. The increasing socialization of women through opportunities emerged in economic and political spheres during the last few decades starting from 1990’s have unfortunately recorded with concomitant impact on increasing violence’s against them. The conventional problems of women in society and family had been surpassed by problems for women in working place and public spheres at present. Similarly the state and society as perpetrators of crime against women have been recorded high than the domestic violence’s a recent trend in gender question. Hence the subaltern position of women has been reinvigorated at a new phase of socio-cultural condition. This paper try explains the depth of the crisis through providing statistical data related to the last decade of 20th century. The data are observed from government publications and news reports. In-depth interviews with victims also have been used as primary data collection method. -

1225-1228 E-ISSN:2581-6063 (Online), ISSN:0972-5210

Plant Archives Volume 20 No. 1, 2020 pp. 1225-1228 e-ISSN:2581-6063 (online), ISSN:0972-5210 A STUDY ON ADOPTION OF ECO-FRIENDLY TECHNOLOGIES AND ITS RELATIONSHIP WIITH THE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE RESPONDENTS Darling B. Suji and A.M. Sathish Kumar Department of Agricultural Extension, Faculty of Agriculture, Annamalai University, Annamalainagar-608002, (Tamilnadu), India. Abstract A Study was conducted in Salem district to find out the adoption of eco-friendly technologies and its relationship with the profile of the respondents and the constraints in the adoption of eco-friendly technologies. The study reveals that 47.50 per cent were found to possess medium level of adoption and 32.50 per cent were found to possess low level of adoption. The education reveals appositively significant relationship with adoption. The study also reveals that farming experience showed a positive and highly significant relationship with the adoption of the respondents on eco-friendly technologies. Lack of knowledge to identify the bio-agents was the foremost personal constraints expressed by majority of the farmers. Key words : Eco-friendly technologies, farming experience, bio-agents. Introduction are recommended by extension workers and practiced Eco-friendly practices are simple, low cost, pollution by farmers. Eco-friendly agricultural technologies are free techniques and operations that are socially and simple, low cost, pollution free, techniques and operations economically accepted. There is an urgent need to that are socially and economically accepted. Eco-friendly develop farming techniques which are sustainable from agricultural technologies have demonstrated their ability environmental, production and socio economic point of not only to produce safer commodities but also to produce view. -

List of Food Safety Officers

LIST OF FOOD SAFETY OFFICER State S.No Name of Food Safety Area of Operation Address Contact No. Email address Officer /District ANDAMAN & 1. Smti. Sangeeta Naseem South Andaman District Food Safety Office, 09434274484 [email protected] NICOBAR District Directorate of Health Service, G. m ISLANDS B. Pant Road, Port Blair-744101 2. Smti. K. Sahaya Baby South Andaman -do- 09474213356 [email protected] District 3. Shri. A. Khalid South Andaman -do- 09474238383 [email protected] District 4. Shri. R. V. Murugaraj South Andaman -do- 09434266560 [email protected] District m 5. Shri. Tahseen Ali South Andaman -do- 09474288888 [email protected] District 6. Shri. Abdul Shahid South Andaman -do- 09434288608 [email protected] District 7. Smti. Kusum Rai South Andaman -do- 09434271940 [email protected] District 8. Smti. S. Nisha South Andaman -do- 09434269494 [email protected] District 9. Shri. S. S. Santhosh South Andaman -do- 09474272373 [email protected] District 10. Smti. N. Rekha South Andaman -do- 09434267055 [email protected] District 11. Shri. NagoorMeeran North & Middle District Food Safety Unit, 09434260017 [email protected] Andaman District Lucknow, Mayabunder-744204 12. Shri. Abdul Aziz North & Middle -do- 09434299786 [email protected] Andaman District 13. Shri. K. Kumar North & Middle -do- 09434296087 kkumarbudha68@gmail. Andaman District com 14. Smti. Sareena Nadeem Nicobar District District Food Safety Unit, Office 09434288913 [email protected] of the Deputy Commissioner , m Car Nicobar ANDHRA 1. G.Prabhakara Rao, Division-I, O/o The Gazetted Food 7659045567 [email protected] PRDESH Food Safety Officer Srikakulam District Inspector, Kalinga Road, 2. K.Kurmanayakulu, Division-II, Srikakulam District, 7659045567 [email protected] LIST OF FOOD SAFETY OFFICER State S.No Name of Food Safety Area of Operation Address Contact No. -

Annual Inspection Proforma for Tnau Research Stations 2019

1 ANNUAL INSPECTION PROFORMA FOR TNAU RESEARCH STATIONS 2019 A. General 1. Name of the Research station : Tapioca and Castor Research Station 2. Location with Altitude, Latitude : Yethapur, Salem district – 636 119 and Longitude Latitude : 11 35’ N Longitude : 78 29’ S 3. Date of start of the station : 01-04-1998 ( Copy of Government / University order to be enclosed) 4. Name and Designation of the : Dr. S. R. Venkatachalam, Professor & Head Professor (PB&G) and Head 5. Total area of the station : 9.54 ha (Details with survey numbers to be enclosed in Annexure) 6. Mandate of the station : Undertaking basic, strategic and applied thrust areas of research in tapioca and castor To act as a lead centre for scientific information and coordinating farmer’s problem solving issues in tapioca and castor Introduction of new technologies for increasing the productivity of tapioca and castor Imparting training on tapioca and castor to the farmers and extension functionaries Providing farm advisory services for various crops in North Western Zone of Tamil Nadu 7. Current Research Agenda : Conservation and characterization of germplasm in Tapioca and Castor Breeding for high yield, quality and resistance to biotic stresses in Tapioca Breeding for high yield, crop duration, yield and resistance to biotic stresses in Castor Standardizing technology package for Castor hybrid YRCH 2 and castor variety YTP 1 for higher productivity Studying the performance of tapioca and castor in Vedharanyam Block. Studying the effect of transplanting method of crop establishment in castor Yield maximization through improved production systems in Castor 2 Soil fertility assessment and improvement in Tapioca Innovative approaches for nutrient management in Tapioca Biological control of insect pests in Castor Integrated pest management in Castor Plant–pest interaction and assessing host plant resistance to major crop pests in Castor Biological control and integrated management strategies for major diseases in Castor 8. -

04.01.2016 TNAU Sends Proposal to Govt. to Boost Pulses Production

04.01.2016 TNAU sends proposal to Govt. to boost pulses production Tamil Nadu Agricultural University has sent a proposal to the State Government to almost double pulses production in the coming season. According to sources, the objective is to take the black gram (urad dal) production from the current average yield of 400-500 kg a hectare to 1,000 kg a hectare. The move is in keeping with the United Nations declaring 2016 as the International Year of Pulses. The sources said that under the proposal, the university will first take up 10,000 of the 40,000 hectare in the four delta districts (Thanjavur, Tiruvarur, Cuddalore and Nagapattinam) in the rice fallow season to double production. The university had tasked the job of identifying the 10,000 hectares to joint directors of agriculture in the districts concerned. In the selected lands, the university will train farmers, hand over ADT 5 and VBN 6 variety seeds and also support farmers by ensuring that they plant using seed drill, which ensures that every sq.m. of the field contained 33 plants. During the 60-65 day growth period, the university would advise and assist the farmers on weed and nutrition management. This would be during the first cultivation season or ‘Thai Pattam’. In the next cultivation season, ‘Chithirai Pattam’, the university would use seeds harvested in the first season to expand the area, the sources said. At the end of both the cultivation seasons, the university would with help from the Agriculture Marketing Department help farmers get a good price. -

Salem District Disaster Management Plan 2018

1 SALEM DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN 2018 Tmt.Rohini.R.Bhajibhakare,I.A.S., Collector, Salem. 2 Sl. No. Content Page No. 1 Introduction 2-12 2 Profile of Salem District 13-36 3 Hazard, Vulnerability and Risk Assessment 37-40 4 Institutional Frame Work 41-102 5 Disaster Preparedness 103-112 6 Disaster Response, Relief and Rehabilitation 113-119 7 Disaster prevention and Mitigation 120-121 8 Revised Goals (2018-2030) 122-194 9 Desilting and Mission 100 success story 195-209 10 Do’s and Don’ts for Disasters 211-229 11 Inventories and machinaries 230-238 12 Important contact numbers 239-296 13 List of Tanks 297-320 14 Annexures 321-329 15 Abbrevations 330-334 Vulnerability Gaps Analysis and Mitigation on 16 release of surplus water from Mettur Dam, 335-353 Salem. 3 DISASTER MANAGEMENT INTRODUCTION The DM Act 2005 uses the following definition for disaster: “Disaster” means a catastrophe, mishap, calamity or grave occurrence in any area, arising from natural or manmade causes, or by accident or negligence which results in substantial loss of life or human suffering or damage to, and destruction of, property, or damage to, or degradation of, environment, and is of such a nature or magnitude as to be beyond the coping capacity of the community of the affected area.” The UNISDR defines disaster risk management as the systematic process of using administrative decisions, organization, operational skills and capacities to implement policies, strategies and coping capacities of the society and communities to lessen the impacts of natural hazards and related environmental and technological disasters. -

Sl.No Region No.Of Works Total Amount (Rs. in Lakhs) 1 Chennai

Kudimaramath Scheme Water Bodies Restoration with Participatory Approach General Abstract Total Amount Sl.No Region No.of works (Rs. In Lakhs) 1 Chennai 299 2500.00 2 Trichy 561 3500.00 3 Madurai 344 2500.00 4 Coimbatore 315 1500.00 Total 1519 10000.00 CHENNAI REGION Kudimaramath Scheme Districtwise Abstract Estimate Amount Sl.No. District No. of Works Rs. In lakhs 1 Thiruvallur 46 433.50 2 Kancheepuram 49 426.50 3 Dharmapuri 21 156.00 4 Krishnagiri 15 108.00 5 Vellore 34 300.00 6 Thiruvanamalai 23 173.00 7 Villupuram 101 808.00 8 Cuddalore 10 95.00 Total 299 2500.00 Kudimaramath Scheme- Water Bodies Restoration CHENNAI REGION , WRD THIRUVALLUR DISTRICT District Estimate Sl.No. wise Name of work Amount Basin Sub Basin Ayacut in Ha. Sl.No Rs. in lakh Restoration by Repairs to sluice and strengthening of tank bund in 1 1 Cherukkanur chitteri in Cherukkanur village in Tiruttani Taluk of 9.60 Chennai Nandhiyar 47.060 Thiruvallur District under Kudimaramathu Scheme. Restoration by Repairs to sluice and strengthening of tank bund in 2 2 Suriyanagaram tank in Suriyanagaram Village in Tiruttani Taluk 9.90 Chennai Nandhiyar 103.260 of Thiruvallur District under Kudimaramathu Scheme. Restoration by Repairs to sluice No.2 and strengthening of tank 3 3 bund in Agoor big tank in Agoor village in Tiruttani Taluk of 9.70 Chennai Nandhiyar 197.290 Thiruvallur District under Kudimaramathu Scheme. Restoration by Repairs to Damaged culvert across Agoor Chitteri 4 4 supply channel in Agoor village in Tiruttani Taluk of Thiruvallur 9.30 Chennai Nandhiyar 40.570 District under Kudimaramathu Scheme. -

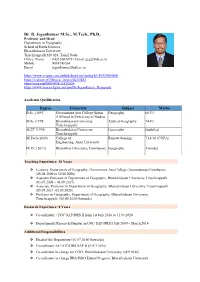

Dr. R. Jegankumar M.Sc., M.Tech., Ph.D

Dr. R. Jegankumar M.Sc., M.Tech., Ph.D., Professor and Head Department of Geography School of Earth Sciences Bharathidasan University Tiruchirappalli 620 024, Tamil Nadu Office: Phone : 04312407079 / Email: [email protected] Mobile 9894748564 Email : [email protected] https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=56539984800 https://vidwan.inflibnet.ac.in/profile/65883 https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2333-3898 https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jegankumar_Rajagopal Academic Qualification Degree University Subject Marks B.Sc.,(1993) Government Arts College Salem Geography 60.3% Affiliated to University of Madras M.Sc (1998) Bharathidasan University, Applied Geography 74.4% Tiruchirappalli SLET (1998) Bharathidasan University, Geography Qualified Tiruchirappalli M.Tech (2000) College of Remote Sensing 7.14/10 (CGPA) Engineering, Anna University Ph.D., (2017) Bharathiar University, Coimbatore Geography Awarded Teaching Experience: 18 Years Lecturer, Department of Geography, Government Arts College (Autonomous) Coimbatore (28.08.2000 to 30.06.2006) Assistant Professor in Department of Geography, Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli (03.07.2006 – 04.09.2017) Associate Professor in Department of Geography, Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli (05.09.2017 -05.09.2020) Professor in Geography, Department of Geography, Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli (06.09.2020 Onwards) Research Experience: 8 Years Co-ordinator - UGC SAP-DRS II from 1st July 2016 to 31.03.2020 Departmental Research Member in UGC SAP-DRS I July 2009 – March 2014 Additional Responsibilities Head of the Department (01.07.2016 Onwards) Co-ordinator for UGC-DRS SAP II (JULY2016) Co-ordinator in-charge for CGIT, Bharathidasan University (SEP 2016) Co-ordinator in-charge IIRS/ISRO Edusat Program, Bharathidasan University Areas of Research Geoinformatics: Mapping & Modelling of Spatial Elements, Health and Well Being, Agroclimatology, Geo-Archaeology Research Supervision / Guidance Program of Study Completed Ongoing Ph.D. -

District Statistical Handbook 2016 Salem Tamilnadu.Pdf

“We have the duty of formulating, of summarising and of communicating our conclusions, in intelligence form, in recognition of the right of ‘other’ free minds to utilize them in making ‘their own decisions’.” -R.A.Fisher (Father of Statistics) “It is easy to lie with statistics. It is hard to tell the truth without statistics”. -Andrejs Dunkels District Statistical Handbook 2015-16 Page 1 PREFACE The publication of “District Statistical Hand Book 2015-16 - Salem” presents the latest statistical data on various Socio-Economic aspects of Salem District. Statistical Tables presented in this book highlight the trends in the development and progress in various sectors of Salem District’s economy. I extend my sincere thanks to Dr. V.Irai Anbu, I.A.S, Principal Secretary/Commissioner, Department of Economics and Statistics, Chennai, Thiru. V.Sampath, I.A.S, District Collector, Salem and Thiru.K.Ravi Kumar, M.A., B.Ed., B.L., M.B.A., Regional Joint Director of Statistics, Salem for their valuable support and suggestions offered for enhancing the quality for this publication. The co-operation extended by various Heads of Departments of State and Central Governments, Public Sector Undertakings and Other organizations in bringing out this book is acknowledged with profound gratitude.It is hoped that this Hand Book will be a useful reference book to Administrators, Planners, Scholars, Statisticians, Economists and to all those who are interested in the Socio- Economic Planning of Salem District. I express my appreciation to all the Officers and Staff of this office for compiling the data relating to this Hand Book. -

“We Have the Duty of Formulating, of Summarising and of Communicating Our Conclusions, in Intelligence Form, in Recognition Of

“We have the duty of formulating, of summarising and of communicating our conclusions, in intelligence form, in recognition of the right of ‘other’ free minds to utilize them in making ‘their own decisions’.” -R.A.Fisher (Father of Statistics) “It is easy to lie with statistics. It is hard to tell the truth without statistics”. -Andrejs Dunkels PREFACE The publication of “District Statistical Hand Book 2018-19- Salem” presents the latest statistical data on various Socio-Economic aspects of Salem District. Statistical Tables presented in this book highlight the trends in the development and progress in various sectors of Salem District’s economy. I extend my sincere thanks toThiru.Atul Anand, I.A.S.Commissioner, Department of Economics and Statistics, Chennai, Thiru.S.A.Raman, I.A.S, District Collector, Salem and Thiru K.Balasubramaniyan., M.A., Regional Joint Director of Statistics, Salem for their valuable support and suggestions offered for enhancing the quality for this publication. The co-operation extended by various Heads of Departments of State and Central Governments, Public Sector Undertakings and Other organizations in bringing out this book is acknowledged with profound gratitude.It is hoped that this Hand Book will be a useful reference book to Administrators, Planners, Scholars, Statisticians, Economistsand to all those who are interested in the Socio- Economic Planning of Salem District. I express my appreciation to all the Officers and Staff of this office for compiling the data relating to this Hand Book. Suggestions for improving future compilations are most welcome. Place: Salem Date: 10.2019 Deputy Director of Statistics, Salem SALIENT FEATURES OF SALEM DISTRICT I. -

Kvk-Salem/Wp-Content/Uploads/Sites/79/2020/01/AR-KVK-Salem-2018-19-14.05.2019

ANNUAL REPORT (April 2018-March 2019) OF KVK, SALEM APR SUMMARY (Note: While preparing summary, please don’t add or delete any row or columns) 1. Training Programmes Clientele No. of Male Female Total Courses participants Farmers & farm women 46 2418 1219 3637 Rural youths 4 68 12 80 Extension functionaries 1 28 12 40 Sponsored Training 2 38 2 40 Vocational Training 2 30 10 40 Total 55 2582 1255 3837 2. Frontline demonstrations Enterprise No. of Farmers Area (ha) Units/Animals Oilseeds 20 8 Pulses 20 8 Cereals and millets 20 8 Vegetables 10 4 Other crops (Cotton & Guava) 20 8 Total 90 36 Livestock & Fisheries 10 10 Other enterprises Total 100 36 Grand Total 100 36 10 3. Technology Assessment & Refinement Category No. of Technology No. of No. of Assessed & Refined Trials Farmers Technology Assessed Crops 7 30 30 Livestock 1 10 10 Various enterprises 4 45 115 Total Technology Refined Crops Livestock Various enterprises Total Grand Total 12 85 155 4. Extension Programmes Category No. of Programmes Total Participants Extension activities 2264 9073 Other extension activities 263 342 Total 2527 9415 ICAR KVK Salem, Annual Report 2018-19 Page 1 5. Mobile Advisory Services Types of Type of messages Messages Crop Livestock Weather Marketing Awareness Other Total enterprise of of No of No of No of No of No No of No of No of No of No of No of No of No of No of No of farmers farmers farmers farmers farmers farmers farmers messages messages messages messages messages messages messages Text only 6 1567 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 6 1567 Voice only 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Voice & 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Text both Total 6 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 6 Messages Total 1567 1567 farmers Benefitted 6. -

![189] Chennai, Monday, May 11, 2020 Chithirai 28, Saarvari, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2051](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0898/189-chennai-monday-may-11-2020-chithirai-28-saarvari-thiruvalluvar-aandu-2051-5030898.webp)

189] Chennai, Monday, May 11, 2020 Chithirai 28, Saarvari, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2051

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2020 [Price: Rs. 6.40 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 189] CHENNAI, monday, may 11, 2020 Chithirai 28, Saarvari, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2051 Part II—Section 2 Notifications or Orders of interest to a Section of the public issued by Secretariat Departments. NOTIFicationS BY GOVERNMENT REVENUE AND DISASTER MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT DISASTER MANAGEMENT ACT, 2005 - COVID-19 - DEMARCation OF Containment ZONE to CONTROL CORONA VIRUS - LIST OF Containment ZONE AS ON 08-05-2020 - NOTIFICation - ISSUED. No. II(2)/REVDM/232(b)/2020. The following Government Order is Published: [G.O. Ms. No. 230, Revenue and Disaster Management (Dm-II),11th May 2020, CˆF¬ó 28, ꣘õK, F¼õœÀõ˜ ݇´---2051.] Read: 1. Go.Ms.No.217, Revenue and Disaster Management (DM-II) Department, dated 3-5-2020. 2. Go.Ms.No.221, Revenue and Disaster Management (DM-II) Department, dated 3-5-2020. 3. From the Health and Family Welfare Department, Proposal dated 10-5-2020. Order: The Notification List of Containment Zones as on 08-05-2020 under Disaster Management Act, 2005. [1] II-2 Ex. (189) 2 TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE EXtraordinary List of Containment Zones as on 08-05-2020. S.No District Containment Zones Pincode S.No District Containment Zones Pincode 1 Ariyalur Ulliyakudi 621701 40 Ariyalur Munithiraiyanpattinam 621704 2 Ariyalur Kolaiyanur 621704 41 Ariyalur Muniyangurichi 621651 3 Ariyalur Zone -10 Kavanur 621704 42 Ariyalur naduvalur 621904 4 Ariyalur Zone