478 Part Four: Airpower in the Land Battle the Telegram Referred To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloadable Content the Supermarine

AIRFRAME & MINIATURE No.12 The Supermarine Spitfire Part 1 (Merlin-powered) including the Seafire Downloadable Content v1.0 August 2018 II Airframe & Miniature No.12 Spitfire – Foreign Service Foreign Service Depot, where it was scrapped around 1968. One other Spitfire went to Argentina, that being PR Mk XI PL972, which was sold back to Vickers Argentina in March 1947, fitted with three F.24 cameras with The only official interest in the Spitfire from the 8in focal length lens, a 170Imp. Gal ventral tank Argentine Air Force (Fuerca Aerea Argentina) was and two wing tanks. In this form it was bought by an attempt to buy two-seat T Mk 9s in the 1950s, James and Jack Storey Aerial Photography Com- PR Mk XI, LV-NMZ with but in the end they went ahead and bought Fiat pany and taken by James Storey (an ex-RAF Flt Lt) a 170Imp. Gal. slipper G.55Bs instead. F Mk IXc BS116 was allocated to on the 15th April 1947. After being issued with tank installed, it also had the Fuerca Aerea Argentina, but this allocation was the CofA it was flown to Argentina via London, additional fuel in the cancelled and the airframe scrapped by the RAF Gibraltar, Dakar, Brazil, Rio de Janeiro, Montevi- wings and fuselage before it was ever sent. deo and finally Buenos Aires, arriving at Morón airport on the 7th May 1947 (the exhausts had burnt out en route and were replaced with those taken from JF275). Storey hoped to gain an aerial mapping contract from the Argentine Government but on arrival was told that his ‘contract’ was not recognised and that his services were not required. -

समाचार पत्रं से चवयत अंश Newspapers Clippings

Aug 2021 समाचार प配रं से चवयत अंश Newspapers Clippings A Daily service to keep DRDO Fraternity abreast with DRDO Technologies, Defence Technologies, Defence Policies, International Relations and Science & Technology खंड : 46 अंक : 157 10 अगस्त 2021 Vol.: 46 Issue : 157 10 August 2021 रक्षा विज्ञान पुस्तकालय Defence Science Library रक्षा िैज्ञावनक सूचना एिं प्रलेखन कᴂद्र Defence Scientific Information & Documentation Centre मेटकॉफरक्षा हाउस विज्ञान, विल्ली- 110पुस्तकालय 054 MetcalfeDefence House, Science Delhi -Library 110 054 रक्षा िैज्ञावनक सूचना एिं प्रलेखन कᴂद्र Defence Scientific Information & Documentation Centre मेटकॉफ हाउस, विल्ली - 110 054 Metcalfe House, Delhi- 110 054 CONTENTS S. No. TITLE Page No. DRDO News 1-14 DRDO Technology News 1-12 1. Pune: DIAT, SETS hold joint workshop on quantum security, FPGA 1 2. Apart from making missiles and rockets, now DRDO is also transferring 2 technology 3. Govt. must consider reintroduction of tax incentives for R&D in defence: Jayant 3 D. Patil, L&T 4. Indian Navy arrives for joint exercises 11 COVID 19: DRDO’s Contribution 12-14 5. 4 ऑ啍सीजन प्ल車ट ज쥍द हⴂगे शु셂:6 महीने बलद प्रतिददन मम्ेगी 26 ्लख ्ीटर ऑ啍सीजन, 15 12 ददनⴂ मᴂ एमसीएच हॉस्पिट् मᴂ िह्ल प्ल車ट होगल चल् ू 6. उ륍मीदⴂ के तनष्कर्ष 13 7. झल車सी मेडिक् कॉ्ेज और ब셁आसलगर सीएचसी को मम्ल आ啍सीजन प्ल車ट, विधलयक 14 और मेयर ने ककयल ्ोकलिषण Defence News 15-27 Defence Strategic: National/International 15-27 8. -

Life and Works of Saint Bernard, Abbot of Clairvaux

J&t. itfetnatto. LIFE AND WORKS OF SAINT BERNARD, ABBOT OF CLA1RVAUX. EDITED BY DOM. JOHN MABILLON, Presbyter and Monk of the Benedictine Congregation of S. Maur. Translated and Edited with Additional Notes, BY SAMUEL J. EALES, M.A., D.C.L., Sometime Principal of S. Boniface College, Warminster. SECOND EDITION. VOL. I. LONDON: BURNS & OATES LIMITED. NEW YORK, CINCINNATI & CHICAGO: BENZIGER BROTHERS. EMMANUBi A $ t fo je s : SOUTH COUNTIES PRESS LIMITED. .NOV 20 1350 CONTENTS. I. PREFACE TO ENGLISH EDITION II. GENERAL PREFACE... ... i III. BERNARDINE CHRONOLOGY ... 76 IV. LIST WITH DATES OF S. BERNARD S LETTERS... gi V. LETTERS No. I. TO No. CXLV ... ... 107 PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH EDITION. THERE are so many things to be said respecting the career and the writings of S. Bernard of Clairvaux, and so high are view of his the praises which must, on any just character, be considered his due, that an eloquence not less than his own would be needed to give adequate expression to them. and able labourer He was an untiring transcendently ; and that in many fields. In all his manifold activities are manifest an intellect vigorous and splendid, and a character which never magnetic attractiveness of personal failed to influence and win over others to his views. His entire disinterestedness, his remarkable industry, the soul- have been subduing eloquence which seems to equally effective in France and in Italy, over the sturdy burghers of and above of Liege and the turbulent population Milan, the all the wonderful piety and saintliness which formed these noblest and the most engaging of his gifts qualities, and the actions which came out of them, rendered him the ornament, as he was more than any other man, the have drawn him the leader, of his own time, and upon admiration of succeeding ages. -

Penttinen, Iver O

Penttinen, Iver O. This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on October 31, 2018. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard First revision by Patrizia Nava, CA. 2018-10-18. Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Penttinen, Iver O. Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical Sketch ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 5 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 6 Image -

Les Continuités Ecologiques Régionales En Hauts-De-France

G MONT-D'ORIGNY MONT-D'ORIGNY PUISIEUX-ET-CLANLIEUPUISIEUX-ET-CLANLIEU Les Continuités Ecologiques HARLY HOMBLIERES SAVY SAINT-QUENTIN THENELLES Régionales en Hauts-de-France MESNIL-SAINT-LAURENT REGNY SAINS-RICHAUMONT DALLON ORIGNY-SAINTE-BENOITE GAUCHY A1 A2 A3 LE HERIE-LA-VIEVILLE NEUVILLE-SAINT-AMAND LANDIFAY-ET-BERTAIGNEMONT B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 SAINS-RICHAUMONT G C1 C2 C3 C4 C5 C6 GRUGIES D1 D2 D3 D4 D5 D6 D7 FONTAINEG-LES-CLERCS SISSY ITANCOURT G E1 E2 E3 E4 E5 E6 E7 CASTRES G F1 F2 F3 F4 F5 F6 F7 PLEINE-SELVE PARPEVILLE G1 G2 G3 G4 G5 G6 CHATILLON-SUR-OISE HOUSSET CONTESCOURT MEZIERES-SUR-OISE G H1 H2 H3 H4 H5 H6 URVILLERS G G RIBEMONT MONCEAU-LE-NEUF-ET-FAUCOUZY I1 I2 I3 I4 G G GG BERTHENICOURT G SERAUCOURT-LE-GRAND G ESSIGNY-LE-GRAND CONTINUITES ECOLOGIQUES G VILLERS-LE-SEC SONS-ET-RONCHERES Réservoirs de biodiversité ALAINCOURT G SERY-LES-MEZIERES CERIZY CHEVRESIS-MONCEAU Réservoirs de Biodiversité de la trame bleue ARTEMPS (cours d'eau de la liste 2 + réservoirs biologiques des Sdage) BENAY Réservoirs de Biodiversité de la trame verte G MOY-DE-L'AISNE CHATILLON-LES-SONS CLASTRES G G Corridors principaux SURFONTAINE HINACOURT G Corridors boisés BRISSY-HAMEGICOURT G Attention: les corridors écologiques, GIBERCOURT au contraire des réservoirs, ne sont BOIS-LES-PARGNY Corridors humides MONTESCOURT-LIZEROLLES pas localisés précisément par le RENANSART schéma. Ils doivent être compris LY-FONTAINE PARGNY-LES-BOIS Corridors littoraux comme des "fonctionnalités LA FERTE-CHEVRESIS écologiques", c'est-à-dire des Corridors ouverts caractéristiques à réunir entre FLAVY-LE-MARTEL deux réservoirs pour répondre FLAVY-LE-MARTEL BRISSAY-CHOIGNY aux besoins des espèces (faune VENDEUIL DERCY Corridors multitrames et flore) et faciliter leurs échanges REMIGNY génétiques et leur dispersion. -

Arrêté Interdépartemental PCB Du 14 Septembre 2009

RtPu.LIqpE Fe.NÇA1sE PJRPFLCTURF .DE LA REGION PLL’ARDiE PREFEc Et P DE LA SOMA PREFECTURE DE L’AISNE. Iieiegere ‘n ]hterServieer de I’JiOiit: et c/Ls irv u aUetq1.tes ‘ r ARRETE INTERPREFECTORAL du PORTANT lNTERDCTlON DE COMMERCIALISER ET RECOMMANDATION DE NE PAS CONSOMMER CERTAINES ESPECES DE POISSONS PECHES DANS LE FLEUVE SOMME ET CERTAINS DE SES AFFLUENTS Le Préfet de la région Picardie Le Préfet de l’Aisne Préfet de la Somme Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur Officier dans l’Ordre national du Mérite 9ruûh Vu e rèplement 1061 t I 881V006 de la CommIssIon oui 9 decrnibnu oient nuance. de teneuus maximales. peur certains contaminants dans les denrées alimenta.Ixes Vu le Code générai des collectivités territoriales, notamment son article L22 15G Vu le Cude de la santé publique, notamment son article L031D2 Vu le Code de l’environnement notamment ses erticies. L436G. 3 à L436G 7; — e t’ e avec es administralons le errer n2Udu9ïi du 21 rsVni 2004. com.c,iété car le u:ecntt nAPPAI 70 eu 16 févner 2009 rehat!t aux tycuunlrs ces créfèts. mc;2:;arnsam,cn eta acuon des de Etst dans Vu l’arrêté interpréiéctc rai du 11 févri.er 200:3 Considérant les résultats d’analyses menée.s enu 2006, en 2007 et 2008 sur les poissons irdiquant lEur contamination par des polychiorobiphenyles; Considérant que cette c.on.•tam ination peut constituer un rlscue potentiel cur la santé humaine •‘fl de ccnsun rnct;cn recul9re c;;e cnutsscns 51cc:, contamines fli< ti or e p’l e tire r tepu - L , ff L D U LUI L’)’ u’ i au: Bi 100 - at des crête ro ra ‘ ces pretectures C e;n r de ARRETE NT Artic cca’ne’vea lsaflou deD HPr e’ 5Jtrj5 rL; rrirtLv,c.,n n o iorem’—’ barbeau caroe s.Iure) rj J ahrients conte’ c-nt le ir h ‘r n-cntts Ju Li etr CaL t Quentn c_ Rate via er 5m Cn e — let r s 0ylrologtquement relies dans Qn jcr’ dans Avre depuis R0 ‘e jumL e ver canfiuer C-’Ov r ‘s S n r dans r° TroIs Dorr cepr s Mrntdiuic. -

PROCES VERBAL DU CONSEIL COMMUNAUTAIRE Mercredi 20 Mai 2020

PROCES VERBAL DU CONSEIL COMMUNAUTAIRE Mercredi 20 mai 2020 L’an deux mille vingt, le mercredi vingt mai, à dix-huit heures, le Conseil Communautaire, légalement convoqué, s’est réuni au nombre prescrit par la Loi, en visioconférence. Ont assisté à la visioconférence : Aizecourt le Bas : Mme Florence CHOQUET - Allaines : M. Bernard BOURGUIGNON - Barleux : M. Éric FRANÇOIS – Brie : M. Marc SAINTOT - Bussu : M. Géry COMPERE - Cartigny : M. Patrick DEVAUX - Devise : Mme Florence BRUNEL - Doingt Flamicourt : M. Francis LELIEUR - Epehy : Mme Marie Claude FOURNET, M. Jean-Michel MARTIN- Equancourt : M. Christophe DECOMBLE - Estrées Mons : Mme Corinne GRU – Eterpigny : : M. Nicolas PROUSEL - Etricourt Manancourt : M. Jean- Pierre COQUETTE - Fins : Mme Chantal DAZIN - Ginchy : M. Dominique CAMUS – Gueudecourt : M. Daniel DELATTRE - Guyencourt-Saulcourt : M. Jean-Marie BLONDELLE- Hancourt : M. Philippe WAREE - Herbécourt : M. Jacques VANOYE - Hervilly Montigny : M. Richard JACQUET - Heudicourt : M. Serge DENGLEHEM - Lesboeufs : M. Etienne DUBRUQUE - Liéramont : Mme Véronique VUE - Longueval : M. Jany FOURNIER- Marquaix Hamelet : M. Bernard HAPPE – Maurepas Leforest : M. Bruno FOSSE - Mesnil Bruntel : M. Jean-Dominique PAYEN - Mesnil en Arrouaise : M. Alain BELLIER - Moislains : Mme Astrid DAUSSIN, M. Noël MAGNIER, M. Ludovic ODELOT - Péronne : Mme Thérèse DHEYGERS, Mme Christiane DOSSU, Mme Anne Marie HARLE, M. Olivier HENNEBOIS, , Mme Catherine HENRY, Mr Arnold LAIDAIN, M. Jean-Claude SELLIER, M. Philippe VARLET - Roisel : M. Michel THOMAS, M. Claude VASSEUR – Sailly Saillisel : Mme Bernadette LECLERE - Sorel le Grand : M. Jacques DECAUX - Templeux la Fosse : M. Benoit MASCRE - Tincourt Boucly : M Vincent MORGANT - Villers-Carbonnel : M. Jean-Marie DEFOSSEZ - Villers Faucon : Mme Séverine MORDACQ- Vraignes en Vermandois : Mme Maryse FAGOT. Etaient excusés : Biaches : M. -

Calendriers Par Journée

DISTRICT AISNE Calendriers par journée Seniors 2ème Division / Phase 1 Groupe D 31141 11 Début été : 15H Début hiver : 15H Brissy Ham. Us 1 à Brissy Hamegicourt Etreillers Fc 1 à Etreillers Frieres Fc 1 à Frieres Faillouel Holnon Fc 3 à Holnon Itancourt Neuville 3 à Itancourt Mennessis O. 1 à Mennessis Moy De L'Aisne Sas 3 à Moy De L Aisne Ribemont Us 2 à Ribemont St Quent Clastres 1 à Clastres St Simon Ca 1 à Seraucourt Le Grand Travecy Fc 1 à Travecy Vouel Us 2 à Tergnier Journée 01 04/09/2011 Journée 12 12/02/2012 Journée 09 04/12/2011 Journée 20 13/05/2012 Ribemont Us 2 - Travecy Fc 1 11H Moy De L'Aisne Sas 3 - Vouel Us 2 St Quent Clastres 1 - Mennessis O. 1 Etreillers Fc 1 - St Quent Clastres 1 Vouel Us 2 - Itancourt Neuville 3 Brissy Ham. Us 1 - Ribemont Us 2 Frieres Fc 1 - Brissy Ham. Us 1 Itancourt Neuville 3 - Mennessis O. 1 Holnon Fc 3 - Etreillers Fc 1 Holnon Fc 3 - Travecy Fc 1 St Simon Ca 1 - Moy De L'Aisne Sas 3 11H St Simon Ca 1 - Frieres Fc 1 Journée 02 11/09/2011 Journée 13 19/02/2012 Journée 10 18/12/2011 Journée 21 27/05/2012 Ribemont Us 2 - St Quent Clastres 1 Ribemont Us 2 - Itancourt Neuville 3 Etreillers Fc 1 - St Simon Ca 1 St Quent Clastres 1 - Brissy Ham. Us 1 Brissy Ham. Us 1 - Holnon Fc 3 Vouel Us 2 - Etreillers Fc 1 Itancourt Neuville 3 - Frieres Fc 1 Frieres Fc 1 - Moy De L'Aisne Sas 3 11H Mennessis O. -

Montage Fiches Rando

Leaflet Walks and hiking trails Haute-Somme and Poppy Country 2 La Courtemanche Stroll between the Time: 2 hours 40 Somme, the Canal du Nord, the marshes and Distance: 8 km the plains to enjoy Route: easy authentic landscapes where History is never Leaving from: Square in very far away. Voyennes Voyennes, 21 km south of Péronne, 7 km east of Nesle Abbeville Albert Péronne Amiens n i z Voyennes a B . Ham C Nesle Montdidier © 1 From the square in Voyennes, of trees. A stone pays tribute to straight on. As you approach turn left. Pass in front of the Sergeant Soudry, killed on 1st Voyennes, turn right. Cross the church. Go toward the cemetery. September 1918, during the final D89. Pass the football stadium. Carry on down the footpath. German assaults in the battle of 6 Join the road again. As you The church of Saint Étienne the Somme on the river Ingon. come out of Voyennes, turn was destroyed during the three Since 20th June 1944, the left. Take the footpath as far as wars of 1870, 1914 and 1945. It Republic P47 Thunderbolt of the Canal de la Somme. was rebuilt in the style of the first Benjamin Hodges has been resting 7 Walk back up to Voyennes by half of the 20th century. Village at the bottom of an old peat bog Rue du Quai and return to the life follows the rhythm of the in the village marshes. The 18th- town hall. marshes and ponds. century washhouse has been 2 Keep left at the fork, in front of completely restored. -

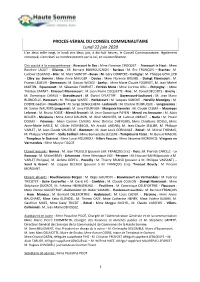

Procès Verbal Du 22 Juin 2020

PROCES-VERBAL DU CONSEIL COMMUNAUTAIRE Lundi 22 juin 2020 L’an deux mille vingt, le lundi vint deux juin, à dix-huit heures, le Conseil Communautaire, légalement convoqué, s’est réuni au nombre prescrit par la Loi, en visioconférence. Ont assisté à la visioconférence : Aizecourt le Bas : Mme Florence CHOQUET - Aizecourt le Haut : Mme Roseline LAOUT - Allaines : M. Bernard BOURGUIGNON - Barleux : M. Éric FRANÇOIS – Biaches : M. Ludovic LEGRAND - Brie : M. Marc SAINTOT - Bussu : M. Géry COMPERE - Cartigny : M. Philippe GENILLIER - Cléry sur Somme : Mme Anne MAUGER - Devise : Mme Florence BRUNEL - Doingt Flamicourt : M. Francis LELIEUR - Driencourt : M. Gaston WIDIEZ - Epehy : Mme Marie Claude FOURNET, M. Jean-Michel MARTIN- Equancourt : M. Sébastien FOURNET - Estrées Mons : Mme Corinne GRU – Eterpigny : : Mme Thérèse CAPART - Etricourt Manancourt : M. Jean-Pierre COQUETTE - Fins : M. Daniel DECODTS - Ginchy : M. Dominique CAMUS – Gueudecourt : M. Daniel DELATTRE - Guyencourt-Saulcourt : M. Jean-Marie BLONDELLE- Hancourt : M. Philippe WAREE - Herbécourt : M. Jacques VANOYE - Hervilly Montigny : M. DODRE Gaëtan - Heudicourt : M. Serge DENGLEHEM - Lesboeufs : M. Etienne DUBRUQUE - Longavesnes : M. Xavier WAUTERS Longueval : M. Jany FOURNIER- Marquaix Hamelet : M. Claude CELMA – Maurepas Leforest : M. Bruno FOSSÉ - Mesnil Bruntel : M. Jean-Dominique PAYEN - Mesnil en Arrouaise : M. Alain BELLIER - Moislains : Mme Astrid DAUSSIN, M. Noël MAGNIER, M. Ludovic ODELOT - Nurlu : M. Pascal DOUAY - Péronne : Mme Carmen CIVIERO, Mme Thérèse DHEYGERS, Mme Christiane DOSSU, Mme Anne-Marie HARLÉ, M. Olivier HENNEBOIS, Mr Arnold LAIDAIN, M. Jean-Claude SELLIER, M. Philippe VARLET , M. Jean Claude VAUCELLE - Rancourt : M. Jean Louis CORNAILLE - Roisel : M. Michel THOMAS, M. Philippe VASSANT – Sailly Saillisel : Mme Bernadette LECLERE - Templeux la Fosse : M. -

CC De La Haute Somme (Combles - Péronne - Roisel) (Siren : 200037059)

Groupement Mise à jour le 01/07/2021 CC de la Haute Somme (Combles - Péronne - Roisel) (Siren : 200037059) FICHE SIGNALETIQUE BANATIC Données générales Nature juridique Communauté de communes (CC) Commune siège Péronne Arrondissement Péronne Département Somme Interdépartemental non Date de création Date de création 28/12/2012 Date d'effet 31/12/2012 Organe délibérant Mode de répartition des sièges Répartition de droit commun Nom du président M. Eric FRANCOIS Coordonnées du siège Complément d'adresse du siège 23 Avenue de l'Europe Numéro et libellé dans la voie Distribution spéciale Code postal - Ville 80200 PERONNE Téléphone Fax Courriel [email protected] Site internet www.coeurhautesomme.fr Profil financier Mode de financement Fiscalité professionnelle unique Bonification de la DGF non Dotation de solidarité communautaire (DSC) non Taxe d'enlèvement des ordures ménagères (TEOM) oui Autre taxe non Redevance d'enlèvement des ordures ménagères (REOM) non Autre redevance non Population Population totale regroupée 27 799 1/5 Groupement Mise à jour le 01/07/2021 Densité moyenne 59,63 Périmètre Nombre total de communes membres : 60 Dept Commune (N° SIREN) Population 80 Aizecourt-le-Bas (218000123) 55 80 Aizecourt-le-Haut (218000131) 69 80 Allaines (218000156) 460 80 Barleux (218000529) 238 80 Bernes (218000842) 354 80 Biaches (218000974) 391 80 Bouchavesnes-Bergen (218001097) 291 80 Bouvincourt-en-Vermandois (218001212) 151 80 Brie (218001345) 332 80 Buire-Courcelles (218001436) 234 80 Bussu (218001477) 220 80 Cartigny (218001709) 753 80 Cléry-sur-Somme -

Guide to The

Guide to the St. Martin WWI Photographic Negative Collection 1914-1918 7.2 linear feet Accession Number: 66-98 Collection Number: FW66-98 Arranged by Jack McCracken, Ken Rice, and Cam McGill Described by Paul A. Oelkrug July 2004 Citation: The St. Martin WWI Photographic Negative Collection, FW66-98, Box number, Photograph number, History of Aviation Collection, Special Collections Department, McDermott Library, The University of Texas at Dallas. Special Collections Department McDermott Library, The University of Texas at Dallas Revised 8/20/04 Table of Contents Additional Sources ...................................................................................................... 3 Series Description ....................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ...................................................................................................... 4 Provenance Statement ................................................................................................. 4 Literary Rights Statement ........................................................................................... 4 Note to the Researcher ................................................................................................ 4 Container list ............................................................................................................... 5 2 Additional Sources Ed Ferko World War I Collection, George Williams WWI Aviation Archives, The History of Aviation Collection,