Chosen Peoples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategic Peacebuilding- the Role of Civilians and Civil Society in Preventing Mass Atrocities in South Sudan

SPECIAL REPORT Strategic Peacebuilding The Role of Civilians and Civil Society in Preventing Mass Atrocities in South Sudan The Cases of the SPLM Leadership Crisis (2013), the Military Standoff at General Malong’s House (2017), and the Wau Crisis (2016–17) NYATHON H. MAI JULY 2020 WEEKLY REVIEW June 7, 2020 The Boiling Frustrations in South Sudan Abraham A. Awolich outh Sudan’s 2018 peace agreement that ended the deadly 6-year civil war is in jeopardy, both because the parties to it are back to brinkmanship over a number S of mildly contentious issues in the agreement and because the implementation process has skipped over fundamental st eps in a rush to form a unity government. It seems that the parties, the mediators and guarantors of the agreement wereof the mind that a quick formation of the Revitalized Government of National Unity (RTGoNU) would start to build trust between the leaders and to procure a public buy-in. Unfortunately, a unity government that is devoid of capacity and political will is unable to address the fundamentals of peace, namely, security, basic services, and justice and accountability. The result is that the citizens at all levels of society are disappointed in RTGoNU, with many taking the law, order, security, and survival into their own hands due to the ubiquitous absence of government in their everyday lives. The country is now at more risk of becoming undone at its seams than any other time since the liberation war ended in 2005. The current st ate of affairs in the country has been long in the making. -

Long-Distance Peacebuilding: the Experiences of the South Sudanese and Sri Lankan Diasporas in Australia

LONG-DISTANCE PEACEBUILDING: THE EXPERIENCES OF THE SOUTH SUDANESE AND SRI LANKAN DIASPORAS IN AUSTRALIA Denise Cauchi NOVEMBER 2018 Acknowledgements This report was produced through a collaboration between Diaspora Action Australia and the University of Melbourne Social Equity Institute’s Community Fellows Program. To the peacebuilders who participated in this research: thank you for your time, patience, wisdom, commitment and generosity of spirit. It is hoped that this report will be of use to you and your communities. A deep debt of gratitude is owed to Nimity James for her tireless transcribing, along with Ganiji Amendi and Andrés Dávila Cauchi. It is hard to imagine how this report would have been written without the advice and guidance provided by Associate Professor Jennifer Balint from Criminology in the University of Melbourne’s School of Social and Political Sciences, who was both intellectually generous and patient throughout. Finally, the author would like to thank Richard Williams and the team at the Social Equity Institute and Denise Goldfinch at Diaspora Action Australia for their support during this project. Design and layout: Elena Lobazova Copyright © Diaspora Action Australia and University of Melbourne 2018. Contents Executive Summary 4 Section 1. Introduction 8 1.1 Research scope 9 1.2 Key findings 9 1.3 Methodology 9 1.4 Structure of this report 10 Section 2. Diaspora community contexts 11 2.1 South Sudanese diaspora 11 2.2 Sri Lankan diaspora 12 Section 3. Findings: Building peace through inter-ethnic harmony 14 3.1 Community harmony in Australia 14 3.2 Advocacy 18 3.3 Peacebuilding in countries of origin 20 3.4 Embodying and modelling change 25 Section 4. -

Sudan in Crisis

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Faculty Publications and Other Works by History: Faculty Publications and Other Works Department 7-2019 Sudan in Crisis Kim Searcy Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/history_facpubs Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Searcy, Kim. Sudan in Crisis. Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective, 12, 10: , 2019. Retrieved from Loyola eCommons, History: Faculty Publications and Other Works, This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications and Other Works by Department at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History: Faculty Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. © Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective, 2019. vol. 12, issue 10 - July 2019 Sudan in Crisis by Kim Searcy A celebration of South Sudan's independence in 2011. Editor's Note: Even as we go to press, the situation in Sudan continues to be fluid and dangerous. Mass demonstrations brought about the end of the 30-year regime of Sudan's brutal leader Omar al-Bashir. But what comes next for the Sudanese people is not at all certain. This month historian Kim Searcy explains how we got to this point by looking at the long legacy of colonialism in Sudan. Colonial rule, he argues, created rifts in Sudanese society that persist to this day and that continue to shape the political dynamics. -

Secretary-General's Report on South Sudan (September 2020)

United Nations S/2020/890 Security Council Distr.: General 8 September 2020 Original: English Situation in South Sudan Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 2514 (2020), by which the Council extended the mandate of the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) until 15 March 2021 and requested me to report to the Council on the implementation of the Mission’s mandate every 90 days. It covers political and security developments between 1 June and 31 August 2020, the humanitarian and human rights situation and progress made in the implementation of the Mission’s mandate. II. Political and economic developments 2. On 17 June, the President of South Sudan, Salva Kiir, and the First Vice- President, Riek Machar, reached a decision on responsibility-sharing ratios for gubernatorial and State positions, ending a three-month impasse on the allocations of States. Central Equatoria, Eastern Equatoria, Lakes, Northern Bahr el-Ghazal, Warrap and Unity were allocated to the incumbent Transitional Government of National Unity; Upper Nile, Western Bahr el-Ghazal and Western Equatoria were allocated to the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army in Opposition (SPLM/A-IO); and Jonglei was allocated to the South Sudan Opposition Alliance. The Other Political Parties coalition was not allocated a State, as envisioned in the Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan, in which the coalition had been guaranteed 8 per cent of the positions. 3. On 29 June, the President appointed governors of 8 of the 10 States and chief administrators of the administrative areas of Abyei, Ruweng and Pibor. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/24/2021 04:59:59AM Via Free Access “They Are Now Community Police” 411

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 410-434 brill.com/ijgr “They Are Now Community Police”: Negotiating the Boundaries and Nature of the Government in South Sudan through the Identity of Militarised Cattle-keepers Naomi Pendle PhD Candidate, London School of Economics, London, UK [email protected] Abstract Armed, cattle-herding men in Africa are often assumed to be at a relational and spatial distance from the ‘legitimate’ armed forces of the government. The vision constructed of the South Sudanese government in 2005 by the Comprehensive Peace Agreement removed legitimacy from non-government armed groups including localised, armed, defence forces that protected communities and cattle. Yet, militarised cattle-herding men of South Sudan have had various relationships with the governing Sudan Peoples’ Liberation Movement/Army over the last thirty years, blurring the government – non government boundary. With tens of thousands killed since December 2013 in South Sudan, questions are being asked about options for justice especially for governing elites. A contextual understanding of the armed forces and their relationship to gov- ernment over time is needed to understand the genesis and apparent legitimacy of this violence. Keywords South Sudan – policing – vigilantism – transitional justice – war crimes – security © NAOMI PENDLE, 2015 | doi 10.1163/15718115-02203006 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 (CC-BY-NC 4.0) License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/Downloaded from Brill.com09/24/2021 04:59:59AM via free access “they Are Now Community Police” 411 1 Introduction1 On 15 December 2013, violence erupted in Juba, South Sudan among Nuer sol- diers of the Presidential Guard. -

Wartime Trade and the Reshaping of Power in South Sudan Learning from the Market of Mayen Rual South Sudan Customary Authorities Project

SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES pROjECT WARTIME TRADE AND THE RESHAPING OF POWER IN SOUTH SUDAN LEARNING FROM THE MARKET OF MAYEN RUAL SOUTH SUDAN customary authorities pROjECT Wartime Trade and the Reshaping of Power in South Sudan Learning from the market of Mayen Rual NAOMI PENDLE AND CHirrilo MADUT ANEI Published in 2018 by the Rift Valley Institute PO Box 52771 GPO, 00100 Nairobi, Kenya 107 Belgravia Workshops, 159/163 Marlborough Road, London N19 4NF, United Kingdom THE RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE (RVI) The Rift Valley Institute (www.riftvalley.net) works in eastern and central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. THE AUTHORS Naomi Pendle is a Research Fellow in the Firoz Lalji Centre for Africa, London School of Economics. Chirrilo Madut Anei is a graduate of the University of Bahr el Ghazal and is an emerging South Sudanese researcher. SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES PROJECT RVI’s South Sudan Customary Authorities Project seeks to deepen the understand- ing of the changing role of chiefs and traditional authorities in South Sudan. The SSCA Project is supported by the Swiss Government. CREDITS RVI EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Mark Bradbury RVI ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF RESEARCH AND COMMUNICATIONS: Cedric Barnes RVI SOUTH SUDAN PROGRAMME MANAGER: Anna Rowett RVI SENIOR PUBLICATIONS AND PROGRAMME MANAGER: Magnus Taylor EDITOR: Kate McGuinness DESIGN: Lindsay Nash MAPS: Jillian Luff,MAPgrafix ISBN 978-1-907431-56-2 COVER: Chief Morris Ngor RIGHTS Copyright © Rift Valley Institute 2018 Cover image © Silvano Yokwe Alison Text and maps published under Creative Commons License Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Available for free download from www.riftvalley.net Printed copies are available from Amazon and other online retailers. -

Village Assessment Survey Rumbek Centre County

Village Assessment Survey COUNTY ATLAS 2013 Rumbek Centre County Lakes State Village Assessment Survey The Village Assessment Survey (VAS) has been used by IOM since 2007 and is a comprehensive data source for South Sudan that provides detailed information on access to basic services, infra- structure and other key indicators essential to informing the development of efficient reintegra- tion programmes. The most recent VAS represents IOM’s largest effort to date encompassing 30 priority counties comprising of 871 bomas, 197 payams, 468 health facilities, and 1,277 primary schools. There was a particular emphasis on assessing payams outside state capitals, where com- paratively fewer comprehensive assessments have been carried out. IOM conducted the assess- ment in priority counties where an estimated 72% of the returnee population (based on esti- mates as of 2012) has resettled. The county atlas provides spatial data at the boma level and should be used in conjunction with the VAS county profile. Four (4) Counties Assessed Planning Map and Dashboard..…………Page 1 WASH Section…………..………...Page 14 - 20 General Section…………...……...Page 2 - 5 Natural Source of Water……...……….…..Page 14 Main Ethnicities and Languages.………...Page 2 Water Point and Physical Accessibility….…Page 15 Infrastructure and Services……...............Page 3 Water Management & Conflict....….………Page 16 Land Ownership and Settlement Type ….Page 4 WASH Education...….……………….…….Page 17 Returnee Land Allocation Status..……...Page 5 Latrine Type and Use...………....………….Page 18 Livelihood -

09.04.20 South Sudan Program

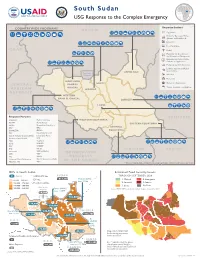

South Sudan USG Response to the Complex Emergency COUNTRYWIDE PROGRAMS Response Sectors: SUDAN Agriculture Economic Recovery, Market Systems, and Livelihoods Education Food Assistance CHAD Health Humanitarian Coordination and Information Management Humanitarian Policy, Studies, Analysis, or Application Multipurpose Cash Assistance Logistics Support and Relief Commodities Abyei Area- UPPER NILE Disputed* Nutrition Protection NORTHERN UNITY Shelter and Settlements CENTRAL BAHR EL GHAZAL Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene AFRICAN WARRAP REPUBLIC WESTERN BAHR EL GHAZAL JONGLEI LAKES Response Partners: ETHIOPIA AAH/USA Mentor Initiative WESTERN EQUATORIA ACTED Mercy Corps EASTERN EQUATORIA ALIMA Nonviolent Peaceforce ARC NRC CENTRAL CONCERN OCHA EQUATORIA CRS Relief International Danish Refugee Council (DRC) Samaritan's Purse Doctors of the World SCF FAO Tearfund ICRC UNHCR IFRC UNICEF IMC VSF/G UGANDA KENYA Internews WFP (UNHAS) IOM WFP DEMOCRATIC IRC WHO REPUBLIC Lutheran World Federation World Vision, Inc. (USA) MEDAIR, SWI WRI OF THE CONGO * Final sovereignty status of Abyei Area pending negotiations between South Sudan and Sudan. IDPs in South Sudan Estimated Food Security Levels # By State " UNMISS IDP Site SUDAN THROUGH SEPTEMBER 2020 # Malakal UNMISS 1: Minimal 4: Emergency 60,000 - 100,000 IDP Site ~813,300 base: 27,900 100,000 - 150,000 Host Communities # 2: Stressed 5: Famine 150,000 - 200,000 ## 3: Crisis No Data Abyei Area - 200,000 - 250,000 Bentiu UNMISS Disputed # Source: FEWS NET, South Sudan Outlook, August - September 2020 base: 111,800 ~9,300 ## ## # # ~233,800# # ## # ##"# # # #"# # ### # #~76,400 # # # ~226,000 # # # # # # # ### Wau UNMISS # ETHIOPIA ##~246,700 # base: 10,000 #"## # ~71,200 ~346,300 # # ~207,200 # ~187,200 # # Bor C.A.R. UNMISS # ~2,600 #"# base: # # 1,900 ## # ~70,900 ## # # # ~60,100 Map reflects FEWS NET # ##"# # # # food security projections # Refugees in Neighboring Countries #~220,800 # at the area level. -

The Greater Pibor Administrative Area

35 Real but Fragile: The Greater Pibor Administrative Area By Claudio Todisco Copyright Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva 2015 First published in March 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Maison de la Paix, Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Emile LeBrun Copy-edited by Alex Potter ([email protected]) Proofread by Donald Strachan ([email protected]) Cartography by Jillian Luff (www.mapgrafix.com) Typeset in Optima and Palatino by Rick Jones ([email protected]) Printed by nbmedia in Geneva, Switzerland ISBN 978-2-940548-09-5 2 Small Arms Survey HSBA Working Paper 35 Contents List of abbreviations and acronyms .................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Introduction and key findings .............................................................................................................................................. -

From Independence to Civil War Atrocity Prevention and US Policy Toward South Sudan

From Independence to Civil War Atrocity Prevention and US Policy toward South Sudan Jon Temin July 2018 CONTENTS Foreword ............................................................................................................................. i Executive Summary .......................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 4 Project Background .......................................................................................................... 7 The South Sudan Context ................................................................................................ 9 Post-Benghazi, Post-Rwanda ...................................................................................... 9 Long US History and Friendship .............................................................................. 10 Hostility Toward Sudan and Moral Equivalence ...................................................... 11 Divergent Perceptions of Influence and Leverage .................................................. 11 Pivotal Periods ................................................................................................................ 13 1. Spring/Summer 2013: Opportunity for Prevention? ........................................... 13 2. Late 2013/Early 2014: The Uganda Question ....................................................... 17 3. Early 2014: Arms Embargo—A -

Sudan, Imperialism, and the Mahdi's Holy

bria_29_3:Layout 1 3/14/2014 6:41 PM Page 6 bria_29_3:Layout 1 3/14/2014 6:41 PM Page 7 the rebels. Enraged mobs rioted in the Believing these victories proved city and killed about 50 Europeans. that Allah had blessed the jihad, huge SUDAN, IMPERIALISM, The French withdrew their fleet, but numbers of fighters from Arab tribes the British opened fire on Alexandria swarmed to the Mahdi. They joined AND THE MAHDI’SHOLYWAR and leveled many buildings. Later in his cause of liberating Sudan and DURING THE AGE OF IMPERIALISM, EUROPEAN POWERS SCRAMBLED TO DIVIDE UP the year, Britain sent 25,000 troops to bringing Islam to the entire world. AFRICA. IN SUDAN, HOWEVER, A MUSLIM RELIGIOUS FIGURE KNOWN AS THE MAHDI Egypt and easily defeated the rebel The worried Egyptian khedive and LED A SUCCESSFUL JIHAD (HOLY WAR) THAT FOR A TIME DROVE OUT THE BRITISH Egyptian army. Britain then returned British government decided to send AND EGYPTIANS. the government to the khedive, who Charles Gordon, the former governor- In the late 1800s, many European Ali established Sudan’s colonial now was little more than a British general of Sudan, to Khartoum. His nations tried to stake out pieces of capital at Khartoum, where the White puppet. Thus began the British occu- mission was to organize the evacua- Africa to colonize. In what is known and Blue Nile rivers join to form the pation of Egypt. tion of all Egyptian soldiers and gov- as the “scramble for Africa,” coun- main Nile River, which flows north to While these dramatic events were ernment personnel from Sudan. -

Battlefields

Nicole C. Vosseler – Beyond the Nile Battlefields Flight of the Khalifa after the Battle of Omdurman, 1898 Robert George Talbot Kelly, ca. 1900 Just like the Crimean War, one of the historical backgrounds in Beneath the Saffron Moon and briefly mentioned in Beyond the Nile, the Mahdist Revolt has hardly left any traces in the consciousness of the Western world - except in that of the British, since Great Britain was the only European power in- volved. If the name of the Mahdi is ever mentioned, it is mostly in relation to the sec- Mohammed Ahmad, the Mahdi ond campaign of 1896-1899 – and then only referring to one lieutenant who took part in this campaign und who later on became famous by his political activities, by premier minister and last but not least by his eccentric character: Winston S. Churchill. This second campaign though was an immediate consequence of the first campaign from 1881 to 1885, the historical backdrop of the novel. Not all regiments dispatched to Egypt and Sudan were involved in every battle, and therefore the depic- tion of the revolt in the novel is guided by the perspective of the Royal Sussex, the regiment of Jeremy, Stephen, Leonard, Royston, and Simon. © Nicole C. Vosseler 1 A regiment that, after the suppression of the ‘Urabi Revolt in Egypt and before its arrival at Khartoum, took part in three battles; one of them is only sketched briefly in the novel, while the other two are an extensive part of the storyline. Battle of El-Teb: February 29th, 1884 Strictly speaking, it should be called “the second Battle of El-Teb”, since this battle occurred as revenge, on the same site where on February 4th the year before, an array of 3,500 Egyptian soldiers under General Valentine Baker was almost completely erased by Osman Digna’s men.