Voices, Values and Visions a Study of the Educate Together Epistemic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Free Learner: a Survey of Experiments in Education. PUB DATE Mar 70 NOTE 34P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 044 048 EM 008 542 AUTHOR Woulf, Constance TITLE The Free Learner: A Survey of Experiments in Education. PUB DATE Mar 70 NOTE 34p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.25 HC-$1.80 DESCRIPTORS Educational Innovation, Educational Philosophy, *Experimental Schools, Nonauthoritarian Classes, *Permissive Environment, Relevance (Education) ABSTRACT As an alternative to the traditional public school, some educators recommend an environment rich in .academic, artistic, and athletic stimuli, from which the child can take what he wants when he wants it. This survey represents the observations of visitors to classrooms in the San Francisco Bay Area which are run on the free learner principle. Twenty private schools, two experimental programs in public schools, and two public schools which are working within the framework et compulsory education are described. As a preface to the descriptions of the actual schools, a fictitious "Hill School" is described which embodies much of the philosophy and practice of the free school ideal.A table of data is also presented which gives information about the student and teacher population and financial status of each of the schools described. This document previously announced as ED 041 480. (JY) U.S. DEPARTMENT Of HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE Of EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY THE FREE LEARNER a survey of experiments in education conducted by CONSTANCE WOULF MARCH 4970 The inspiration for this survey was a book and its author: George Leonard's Education and Ecsta and Leonard's course given at the University of California in Summer 1969. -

Early History of St Rita's

Early History of St Rita’s 1885 - 1960 Version 1 - 2013 PART III – founding charism and traditions: the Sisters of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary. NANO NAGLE Nano Nagle (christened Honora) was born in 1718 of a long- standing Catholic family at Ballygriffin near Mallow in North Cork. Her home lay in the beautiful valley of the Blackwater backed by the Nagle Mountains to the south. Her father was Garret Nagle, a wealthy landowner in the area; her mother, Ann Mathews, was from an equally prominent family in Co. Tipperary. Like others of the old Catholic gentry, the Nagles had managed to hold on to most of their land and wealth during the era of the Penal Laws in the eighteenth century. Edmund Burke, the famous parliamentaria n and orator, who was a relative of Nano Nagle on his mother's side, and had spent his early years in Ballygriffin, described those laws in one trenchant sentence: "Their declared object was to reduce the Catholics in Ireland to a miserable populace, without property, without estimation, without education" The Penal Laws made it unlawful to open a Catholic school at home, and at the same time, forbade them to travel overseas for their education. Nano had to go to a hedge school for her primary education. While the "hedge school" label suggests the classes always took place outdoors next to a hedgerow, classes were sometimes held in a house or barn. A hedgerow is a line of closely spaced shrubs and tree species, planted and trained to form a barrier or to separate a road from adjoining fields or one field from another. -

Ecclesiastical History of Newfoundland, by the Rt

EcclesiasticalhistoryofNewfoundland ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY OF NEW-1 FOUNDLAND. By the Very Reverend M. F. Howlev, D.D.. Prefect Apostolic of | St. George's, West Newfoundland. 8vo, pp. 4»6. Boston : Doyle & Whittle. It must be confessed that Americans, those I of us at least who lire to the southward of (he | Canadian line, know but little of the great tri angular island that lies off the Gulf of St. Law- I rence. To its own inhabitants, indeed, it is in some decree an unknown land, for its interior | can hardly be said as yet to have been thorough ly explored, and there are solitudes among I the lakes and rivers of its remote wilderness that have probably never yet been seen by the eye of civilized man. Its nigged and pictur esque coast is touched only at widely separated points by passcngrr steamers, and but one short railway line has as yet penetrated the forests or disturbed the silence of the rocky fastnesses with its noisy evidence of civilization. Vet these in hospitable shores were early visited by mission aries from the Mother Church, and the opening | of the sixteenth century saw the symbol of the Christian religion reared at several points along the coast. Dr. Howley has been engaged in collecting material for the present history during the greater part of his life, having at an early age developed a taste for accumulating notes bearing upon the history of Newfoundland. The actual work of preparation, however, has occupied rather moie than a year. The learned author has had only one predecessor in the field, the kt Rev. -

In Residency, We Trust

BAY AREA TEACHER TRAINING INSTITUTE | 2017–2018 | ANNUAL REPORT in residency, we trust n i OUR MISSION BATTI’s mission is to provide the comprehensive preparation of aspiring independent and public school teachers and leaders. BATTI graduates educators with the capacity and the determination to: • foster joyous, purposeful, and engaging learning for the full diversity of students • build ever more inclusive, innovative, and inspiring classrooms and schools • contribute to more just, equitable, and sustainable communities Key BATTI features include: • two-year combined MA and credential program designed for full-time working professionals • personalized experiential learning in outstanding public, charter, and independent schools • opportunities to pilot cutting-edge pedagogy and spark school change THE UNIVERSITY OF THE PACIFIC BENERD SCHOOL OF EDUCATION The mission of the Gladys L. Benerd School of Education is to prepare thoughtful, reflective, caring, and collaborative professionals for service to diverse populations. The School of Education directs its efforts toward researching the present and future needs of schools and the community, fostering intellectual and ethical growth, and developing compassion and collegiality through personalized learning experiences. Undergraduate, graduate, and professional preparation programs are developed in accordance with state and national accreditation standards and guidelines to ensure that students who complete these programs will represent the best professional practice in their positions of future leadership in schools and the community. Please visit our website, www.ba-tti.org, to see our introductory videos produced by Portal A Interactive and Youth Beat LITERACY INSTRUCTOR ANA ZAMOST LEADING HER FIRST-YEAR EAST BAY SECTION AT ST. PAUL’S EPISCOPAL SCHOOL real learning environments RESIDENCE, RESONANCE, AND RETENTION This has been another good year for BATTI. -

Education Ireland." for Volume See .D 235 105

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 248 188 SO 015 902 AUTHOR McKirnan, Jim, Ed. TITLE Irish Educational Studies, Vol. 3 No. 2. INSTITUTION Educational Studies Association of Ireland, Ddblin. PUB DATE 83 NOTE 3t3k Financial assistance provided by Industrial Credit. Corporation (Ireland), Allied Irish Banks, Bank ot Ireland, and "Education Ireland." For Volume see .D 235 105. For Volume 3 no. 1, see SO 015 901. PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) Viewpoints (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC15 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Bt3iness Education; Case Studies; Comparative Education; Computer Assisted Instructkon; Educational Finance; *Educational History; *Educational Practices; Educational Theories; Elementary Secondaiy Education; Foreign Countries; High School Graduate0; National Programs; Open Education; ParochialSchools; Peace; Private Schools; Reading Instruction; Science Education IDENTIFIERS *Ireland; *Northern Ireland ABSTRACT Research problems and issues of concern to educators in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland are discussed in 21 papers. Papers fall into the general categorie3 of educational history and current practices. Papers in the first category cover the following topics: a history'oflthe Education Inquiry of 1824-1826, the "hedge" or private primary schools which existed in Ireland prior to institution of the national school system in 1831, the relationship between the Chriptian Brothers schools and the national school system, the relationship between the Irish treasury and the national school system, a history of the Royal.Commission -

A Constructivist Exploration of the Teacher's Role

A CONSTRUCTIVIST EXPLORATION OF THE TEACHER’S ROLE: UNDERSTANDING THE POLICY PRACTICE NAVIGATION BETWEEN: PEDAGOGY, PROFESSIONALISM & VOCATIONALISM MICHAEL F. RYAN (BA, H.Dip, MSc.) Education Doctorate NUI Maynooth Faculty of Social Sciences Education Department Head of Department: Dr Aidan Mulkeen Department of Adult and Community Education Head of Department: Professor Anne Ryan Supervisor: Dr. Ted Fleming May 2010 Acknowledgements I wish to sincerely acknowledge the teaching staff in the Departments of Adult and Community Education & Department of Education at NUI Maynooth, for creating a thoroughly insightful and enjoyable community of learning throughout the three years of the Ed.D. Programme. A particular thanks to Dr. Rose Malone and Dr. Anne B. Ryan who coordinated the programme so successfully and provided scholarly nurturing and encouragement to the group throughout. To my fellow doctoral colleagues: Aideen, Dan, Deborah, Deirdre, Eilis, Gary, Larry, Marie, Mary & Pat – thank you for the wisdom shared, the questions asked and the goodwill throughout. I wish to particularly acknowledge my thesis supervisor, Dr. Ted Fleming – for his: challenging questions, his sharp insights, his ongoing recommendations, sense of humour, but particularly for his belief in the study as it unfolded. Special thanks to Ciaran Lynch and the staff at Tipperary Institute for their valuable support, particularly my colleagues in the Centre For Developing Human Potential (CDHP). To my research participants who engaged so enthusiastically and generously with the study, thank you all for the courage to describe and reflect on your professional lives with honesty. You provided the insights that gave the study its depth and practitioner resonance. I hope, the findings have done justice to your individual and collective experiences. -

Gold and Sunshine, Reminiscences of Early California. by James J. Ayers

Gold and sunshine, reminiscences of early California. By James J. Ayers COL. JAMES J. AYERS GOLD AND SUNSHINE REMINISCENCES OF EARLY CALIFORNIA COLONEL JAMES J. AYERS ILLUSTRATIONS FROM THE COLLECTION OF CHARLES B. TURRILL BOSTON RICHARD G. BADGER THE GORHAM PRESS COPYRIGHT, 1922, BY RICHARD G. BADGER All Rights Reserved ©Cl.A659533 Made in the United States of America The Gorham Press, Boston, U. S. A. Oh, happy days, when youth's wild ways Knew every phase of harmless folly! Oh, blissful nights, whose fierce delights Defied gaunt-featured Melancholy! Gone are they all beyond recall, And I--a shade, a mere reflection-- Am forced to feed my spirit's greed Upon the husks of retrospection! --EUGENE FIELD. v Gold and sunshine, reminiscences of early California. By James J. Ayers http://www.loc.gov/resource/calbk.006 PREFACE For some time past I have had in contemplation to write a book, taking as the subject my experiences in California. A continuous residence of forty-seven years would furnish interesting material for such a book in almost any life. But as mine was cast in channels which threw me in contact with nearly all of the conspicuous figures who have given character and celebrity to our State, and placed me in the whirl of the many events which have given historical interest to California, much of which I saw and a part of which I was, I felt that to present those men and events to the present generation in the way that they appeared to me at the time and in the order of their occurrence, would be a work from which the general reader would derive instruction, the old Californian reminiscent pleasures, and the “tenderfoot” of to-day realize how difficult and beset with obstructions was the pathway of the “tenderfoot” of the argonautic period. -

AVAILABLE from DOCUMENT RESUME Japanese Language

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 393 289 FL 022 541 TITLE Newsletter of the Japanese Language Teachers Network, 1994-1995. INSTITUTION Japanese Language Teachers Network, Urbana, IL. PUB DATE 95 NOTE 184p.; Four issues published per volume year. AVAILABLE FROM Japanese Language Teachers Network, University High School, 1212 W. Springfield Ave., Urbana, IL 61801 ($18 annual subscription). PUB TYPE Collected Works Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT Newsletter of the Japanese Language Teachers Network; v9-10 Dec 1993-Oct 1995 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Articulation (Education); Book Reviews; Class Activities; Classroom Techniques; Computer Software Reviews; Conferences; Cultural Awareness; Higher Education; High Schools; *Japanese; Language Attitudes; *Language Teachers; *Newsletters; Professional Associations; *Second Language Instruction; *Teacher Attitudes; Teaching Methods; Teaching Styles ABSTRACT These newsletter issues explore topics of interest to Japanese language teachers in the United States. Issues contain feature articles, book and computer software reviews, activities and worksheets for classroom use, letters to the editor, news of regional conferences and activities, announcements, new resources, and employment opportunities. Feature articles focus on such topics as: (1) the articulation of high school and university Japanese language programs;(2) individual teaching styles;(3) the expansion of Japanese language instruction in the United States, and the concomitant growth of professional organizations and activities to support such instruction; and (4) teaching effectiveness. (MDM) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** Newsletter of the Japanese Language Teachers Network Vol. 9 No. 1 December 1993 Vol. 9 No. 2 February 1994 Vol. 9 No. 3 May 1994 Vol. 9 No. 4 October 1994 Vol. -

In Old Toledo” Scrapbooks Scope and Contents

Mss. Coll. 147 “In Old Toledo” Scrapbooks Scope and Contents “In Old Toledo” consists of two scrapbooks of photographs clipped from Toledo newspapers, which were an anonymous donation to the library in 2002. Most of the clippings lack identification of newspaper and/or date. However, the scrapbooks contain many photographs of groups of people who are identified in the captions. A Name/Subject index is included to facilitate use of the collection. The extremely poor condition of the clippings and the paper of the scrapbooks led to the decision to photocopy the scrapbooks and to discard the originals. Local History & Genealogy Department Toledo-Lucas County Public Library, Toledo, Ohio Mss. Coll. 147 “In Old Toledo” Scrapbooks Index Name/Subject Vol. Page accidents -- Erie & Western streetcar (1913) 2 7 Adams & Huron Sts. 2 47 Adams & Seventeenth Sts. 1 8 Adams & St. Clair Sts. 2 89, 117 Adams & Superior Sts. (1890) 2 46 Adams Express Co. (1912-13) 1 20 Adams, Arthur 1 36 Adams, Emma 1 32 Adams, Esther 1 36 Adams, Robert 1 10 airships 2 108 Albright, Amelia 1 30 Albright, Jerry 2 119 Albright, Minnie 1 30 Aldrich, Harvey 1 30 Alexander, Walter 2 120 American Bridge Co. 2 93 Ames-Bonner Brush Co. (1899) 2 60 Anderson, Ed 1 21 Ardner, Walter 1 30 Arena A.C. baseball team 1 15 Arend, Mabel 1 37 Armory 1 40 Armory Park 1 19 Arnold, Fannie Johnson 1 31 Ash-Consaul Bridge 2 4, 106 Auburn Ave. & Monroe St. 1 37 Auburndale School (1904) 1 30 Auburndale Shoeing Shop 1 42 Austin, Edna Smith 1 29 Austin, Leio 1 32 Auth, Frank 1 20 automobiles 2 45 automobiles -- "rain drop" (1935) 2 24 automobiles -- Aero Willys scout car (1952) 1 23 automobiles -- Cadillac (1904) 1 5 automobiles -- Cadillac (1910) 2 25 automobiles -- Overland automobile (1904) 1 21 automobiles -- Overland station wagon (1919) 1 20 automobiles -- Rambler (model 19) 2 52 automobiles -- Willys (1908) 1 22 automobiles (1910) 2 23, 25, 50 Local History & Genealogy Department Toledo-Lucas County Public Library, Toledo, Ohio Mss. -

Brian Friel's Appropriation of the O'donnell Clan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2008 Celtic subtleties : Brian Friel's appropriation of the O'Donnell clan. Leslie Anne Singel 1984- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Singel, Leslie Anne 1984-, "Celtic subtleties : Brian Friel's appropriation of the O'Donnell clan." (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1331. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1331 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "CELTIC SUBTLETIES": BRIAN FRIEL'S APPROPRIATION OF THE O'DONNELL CLAN By Leslie Anne Singel B.A., University of Dayton, 2006 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of English University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2008 “CELTIC SUBLETIES”: BRIAN FRIEL’S APPROPRIATION OF THE O’DONNELL CLAN By Leslie Anne Singel B.A., University of Dayton, 2006 A Thesis Approved on April 9, 2008 by the following Thesis Committee: Thesis Director ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to the McGarry family and to Roger Casement 111 ABSTRACT "CELTIC SUBTLETIES": BRIAN FRIEL'S APPROPRIATION OF THE O'DONNELL CLAN Leslie Anne Singel April 11, 2008 This thesis is a literary examination of three plays from Irish playwright Brian Friel, Translations, Philadelphia, Here I Come! and Aristocrats, all of which feature a family ofthe O'Donnell name and all set in the fictional Donegal village of Ballybeg. -

2020 Assessment Institute Participant List Firstname Lastname Title

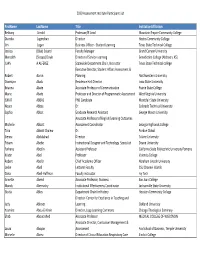

2020 Assessment Institute Participant List FirstName LastName Title InstitutionAffiliation Bethany Arnold Professor/IE Lead Mountain Empire Community College Diandra Jugmohan Director Hostos Community College Jim Logan Business Officer ‐ Student Learning Texas State Technical College Jessica (Blair) Soland Faculty Manager Grand Canyon University Meredith (Stoops) Doyle Director of Service‐Learning Benedictine College (Atchison, KS) JUAN A ALFEREZ Statewide Department Chair, Instructor Texas State Technical college Executive Director, Student Affairs Assessment & Robert Aaron Planning Northwestern University Osomiyor Abalu Residence Hall Director Iowa State University Brianna Abate Associate Professor of Communication Prairie State College Marie Abate Professor and Director of Programmatic Assessment West Virginia University ISMAT ABBAS PhD Candidate Montclair State University Noura Abbas Dr. Colorado Technical University Sophia Abbot Graduate Research Assistant George Mason University Associate Professor of English/Learning Outcomes Michelle Abbott Assessment Coordinator Georgia Highlands College Talia Abbott Chalew Dr. Purdue Global Sienna Abdulahad Director Tulane University Fitsum Abebe Instructional Designer and Technology Specialist Doane University Farhana Abedin Assistant Professor California State Polytechnic University Pomona Kristin Abel Professor Valencia College Robert Abel Jr Chief Academic Officer Abraham Lincoln University Leslie Abell Lecturer Faculty CSU Channel Islands Dana Abell‐Huffman Faculty instructor Ivy Tech Annette -

The Road to Democracy in Irish Primary School Education

Á. Ryan The Road to Democracy in Irish Primary School Education Doctorate of Education 2014 The Road to Democracy in Irish Primary School Education Áine Ryan Doctorate of Education (EdD) School of Education, University of Sheffield August 2014 Abstract This thesis explores the extent to which democratic values and ideals have informed Irish primary school education since independence in 1922. The examination reveals how undemocratic structures, principles and practices have been maintained in primary education by denying equality and freedom of conscience to those not of the majority Catholic faith. It describes how the unique predicament of religious hegemony has persisted because of legislative machinery which, by guaranteeing protection of religious ethos, allows discrimination in enrolment policies, employment practices of primary school teachers, indoctrination across the curriculum and religious control of all teacher training colleges. The social, cultural and political factors which have produced this anomaly of a democratic State having an undemocratic education system are examined, as well as why this situation persists. The possibility for evolution of the democratic discourse within education as well as the forces currently obstructing change is also considered. The arguments presented emerge from a critical policy analysis which draws on democratic theories. In particular, a historical account of Irish primary education is outlined which is informed by Dewey’s philosophy of education, theories referencing participatory democracy and those contemporary sociological concepts which emphasise the role of education in the process of social reproduction and transformation. Gramsci’s ideas on hegemony are applied to analyse the power structures controlling education and theories of selective knowledge, as propounded by Williams and Apple, are applied to the Irish context to highlight the political nature of the curriculum and how it is manipulated to exercise power.