Effect of Freezing on the Initial Colonization of the Carcass with Necrophagous Organisms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Do Longer Sequences Improve the Accuracy of Identification of Forensically Important Calliphoridae Species?

Do longer sequences improve the accuracy of identification of forensically important Calliphoridae species? Sara Bortolini1, Giorgia Giordani2, Fabiola Tuccia2, Lara Maistrello1 and Stefano Vanin2 1 Department of Life Sciences, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy 2 School of Applied Sciences, University of Huddersfield, Huddersfield, United Kingdom ABSTRACT Species identification is a crucial step in forensic entomology. In several cases the calculation of the larval age allows the estimation of the minimum Post-Mortem Interval (mPMI). A correct identification of the species is the first step for a correct mPMI estimation. To overcome the difficulties due to the morphological identification especially of the immature stages, a molecular approach can be applied. However, difficulties in separation of closely related species are still an unsolved problem. Sequences of 4 different genes (COI, ND5, EF-1α, PER) of 13 different fly species collected during forensic experiments (Calliphora vicina, Calliphora vomitoria, Lu- cilia sericata, Lucilia illustris, Lucilia caesar, Chrysomya albiceps, Phormia regina, Cyno- mya mortuorum, Sarcophaga sp., Hydrotaea sp., Fannia scalaris, Piophila sp., Megaselia scalaris) were evaluated for their capability to identify correctly the species. Three concatenated sequences were obtained combining the four genes in order to verify if longer sequences increase the probability of a correct identification. The obtained results showed that this rule does not work for the species L. caesar and L. illustris. Future works on other DNA regions are suggested to solve this taxonomic issue. Subjects Entomology, Taxonomy Submitted 19 March 2018 Keywords ND5, COI, PER, Diptera, EF-1α, Maximum-likelihood, Phylogeny Accepted 17 October 2018 Published 17 December 2018 Corresponding author INTRODUCTION Stefano Vanin, [email protected] Species identification is a crucial step in forensic entomology. -

Protophormia Terraenovae (Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830) (Diptera, Calliphoridae) a New Forensic Indicator to South-Western Europe

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repositorio Institucional de la Universidad de Alicante Ciencia Forense, 12/2015: 137–152 ISSN: 1575-6793 PROTOPHORMIA TERRAENOVAE (ROBINEAU-DESVOIDY, 1830) (DIPTERA, CALLIPHORIDAE) A NEW FORENSIC INDICATOR TO SOUTH-WESTERN EUROPE Anabel Martínez-Sánchez1 Concepción Magaña2 Martin Toniolo Paola Gobbi Santos Rojo Abstract: Protophormia terraenovae larvae are found frequently on corpses in central and northern Europe but are scarce in the Mediterranean area. We present the first case in the Iberian Peninsula where P. terraenovae was captured during autopsies in Madrid (Spain). In the corpse other nec- rophagous flies were found, Lucilia sericata, Chrysomya albiceps and Sarcopha- ga argyrostoma. To calculate the posmortem interval, the life cycle of P. ter- raenovae was studied at constant temperature, room laboratory and natural fluctuating conditions. The total developmental time was 16.61±0.09 days, 16.75±4.99 days in the two first cases. In natural conditions, developmental time varied between 31.22±0.07 days (average temperature: 15.6oC), 15.58±0.08 days (average temperature: 21.5oC) and 14.9±0.10 days (average temperature: 23.5oC). Forensic importance and the implications of other necrophagous Diptera presence is also discussed. Key words: Calliphoridae, forensic entomology, accumulated degrees days, fluctuating temperatures, competition, postmortem interval, Spain. Resumen: Las larvas de Protophormia terraenovae se encuentran con frecuen- cia asociadas a cadáveres en el centro y norte de Europa pero son raras en el área Mediterránea. Presentamos el primer caso en la Península Ibérica don- 1 Departamento de Ciencias Ambientales/Instituto Universitario CIBIO-Centro Iberoame- ricano de la Biodiversidad. -

An Annotated Bibliography of Archaeoentomology

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Distance Master of Science in Entomology Projects Entomology, Department of 4-2020 An Annotated Bibliography of Archaeoentomology Diana Gallagher Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/entodistmasters Part of the Entomology Commons This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Entomology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Distance Master of Science in Entomology Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Diana Gallagher Master’s Project for the M.S. in Entomology An Annotated Bibliography of Archaeoentomology April 2020 Introduction For my Master’s Degree Project, I have undertaken to compile an annotated bibliography of a selection of the current literature on archaeoentomology. While not exhaustive by any means, it is designed to cover the main topics of interest to entomologists and archaeologists working in this odd, dark corner at the intersection of these two disciplines. I have found many obscure works but some publications are not available without a trip to the Royal Society’s library in London or the expenditure of far more funds than I can justify. Still, the goal is to provide in one place, a list, as comprehensive as possible, of the scholarly literature available to a researcher in this area. The main categories are broad but cover the most important subareas of the discipline. Full books are far out-numbered by book chapters and journal articles, although Harry Kenward, well represented here, will be publishing a book in June of 2020 on archaeoentomology. -

Terry Whitworth 3707 96Th ST E, Tacoma, WA 98446

Terry Whitworth 3707 96th ST E, Tacoma, WA 98446 Washington State University E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Published in Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington Vol. 108 (3), 2006, pp 689–725 Websites blowflies.net and birdblowfly.com KEYS TO THE GENERA AND SPECIES OF BLOW FLIES (DIPTERA: CALLIPHORIDAE) OF AMERICA, NORTH OF MEXICO UPDATES AND EDITS AS OF SPRING 2017 Table of Contents Abstract .......................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 Materials and Methods ................................................................................................... 5 Separating families ....................................................................................................... 10 Key to subfamilies and genera of Calliphoridae ........................................................... 13 See Table 1 for page number for each species Table 1. Species in order they are discussed and comparison of names used in the current paper with names used by Hall (1948). Whitworth (2006) Hall (1948) Page Number Calliphorinae (18 species) .......................................................................................... 16 Bellardia bayeri Onesia townsendi ................................................... 18 Bellardia vulgaris Onesia bisetosa ..................................................... -

Arthropod Succession in Whitehorse, Yukon Territory and Compared Development of Protophormia Terraenovae (R.-D.) from Beringia and the Great Lakes Region

Arthropod Succession in Whitehorse, Yukon Territory and Compared Development of Protophormia terraenovae (R.-D.) from Beringia and the Great Lakes Region By Katherine Rae-Anne Bygarski A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Applied Bioscience In The Faculty of Science University of Ontario Institute of Technology July 2012 © Katherine Bygarski, 2012 Certificate of Approval ii Copyright Agreement iii Abstract Forensic medicocriminal entomology is used in the estimation of post-mortem intervals in death investigations, by means of arthropod succession patterns and the development rates of individual insect species. The purpose of this research was to determine arthropod succession patterns in Whitehorse, Yukon Territory, and compare the development rates of the dominant blowfly species (Protophormia terraenovae R.-D.) to another population collected in Oshawa, Ontario. Decomposition in Whitehorse occurred at a much slower rate than is expected for the summer season, and the singularly dominant blowfly species is not considered dominant or a primary colonizer in more southern regions. Development rates of P. terraenovae were determined for both fluctuating and two constant temperatures. Under natural fluctuating conditions, there was no significant difference in growth rate between studied biotypes. Results at repeated 10°C conditions varied, though neither biotype completed development indicating the published minimum development thresholds for this species are underestimated. Keywords: Forensic entomology, decomposition, Protophormia terraenovae, minimum development threshold. iv Acknowledgments This research would not have completed without the collaboration, assistance, guidance and support of so many people and organizations. First and foremost, I would like to thank Dr. Helene LeBlanc for her supervision, support and advice throughout this project. -

Calliphoridae (Diptera) from Southeastern Argentinean Patagonia: Species Composition and Abundance

TrabC n8 25/7/04 6:35 PM Page 85 ISSN 0373-5680 Rev. Soc. Entomol. Argent. 63 (1-2): 85-91, 2004 85 Calliphoridae (Diptera) from Southeastern Argentinean Patagonia: Species Composition and Abundance SCHNACK, Juan A.* and Juan C. MARILUIS ** * División Entomología, Museo de La Plata, Paseo del Bosque. 1900 La Plata, Argentina; e-mail: [email protected] *Servicio de Vectores, ANLIS, Instituto Nacional de Microbiología “Dr. Carlos Malbrán”, Avda. Vélez Sarsfield 563, 1281, Buenos Aires, Argentina; e-mail: [email protected] ■ ABSTRACT. Species composition and spatial and temporal numerical trends of blow flies (Diptera, Calliphoridae) species from three southeastern Patagonia localities: Río Grande (53° 48’ S, 67° 36’ W) (province of Tierra del Fuego), Río Gallegos (51° 34’ S, 69° 14’ W) and Puerto Santa Cruz (50° 04’ S, 68° 27’ W) (province de Santa Cruz) were studied during November, De- cember (1997), and January and February (1998). Results showed remarka- ble differences of overall fly abundance and species relative importance at every sampling site; nevertheless, they shared a poor species representation (S ≤ 6). The cosmopolitan Calliphora vicina Robineau-Desvoidy, the nearly worldwide Lucilia sericata (Meigen), and the native Compsomyiops fulvi- crura (Robineau-Desvoidy) prevailed over the remaining species. Records of Protophormia terraenovae (Robineau-Desvoidy), a species indigenous to the Northern Hemisphere are noteworthy. KEY WORDS. Calliphoridae. Patagonia. Species Composition. Spatial and Temporal Numerical Trends. ■ RESUMEN. Calliphoridae (Diptera) del Sudeste de la Patagonia Argentina: Composición Específica y Abundancia. Se estudian la composición y las va- riaciones numéricas espacio-temporales de especies de Calliphoridae (Dipte- ra) de tres localidades del sudeste patagónico: Río Grande (53° 48’ S, 67° 36’ W) (provincia de Tierra del Fuego), Río Gallegos (51° 34’ S, 69° 14’ W) y Puerto Santa Cruz (50° 04’ S, 68° 27’ W) (provincia de Santa Cruz), a par- tir de muestreos realizados en noviembre, diciembre (1997), enero y febre- ro (1998). -

Bird's Nest Screwworm

Beneficial Species Profile Photo credit: Copyright © 2013 Mardon Erbland, bugguide.net Common Name: Bird’s Nest Screwworm Fly / Holarctic Blow Fly Scientific Name: Protophormia terraenovae Order and Family: Diptera / Calliphoridae Size and Appearance: Length (mm) Appearance Egg 1mm Larva/Nymph Small and white, with about 12 1-12mm segments Adult Dark anterior thoracic spiracle, dark metallic blue in color. 8-12 mm Similar to Phormia regina, however P. terraenovae has longer dorsocentral bristles with acrostichal (set in highest row) bristles short or absent. Pupa (if applicable) 8-9mm Type of feeder (Chewing, sucking, etc.): Sponging in adults / Mouthhooks in larvae Host/s: Larvae develop primarily in carrion. Description of Benefits (predator, parasitoid, pollinator, etc.): This insect is used in Forensic and Medical fields. Maggot Debridement Therapy is the use of maggots to clean and disinfect necrotic flesh wounds. To be usable in this practice, the creature must only target the necrotic tissues. This species ‘fits the bill.’ P. terraenovae is known to produce antibiotics as they feed, helping to fight some infections. P. terraenovae is one of the only blow fly species usable in this way. Blow flies are also one of the first species to arrive on a cadaver. Due to early arrival, they can be the most informative for postmortem investigations. Scientists will collect, note, rear, and identify the species to determine life cycles and developmental rates. Once determined, they can calculate approximate death. This species is also known to cause myiasis in livestock, causing wound strike and death. References: Species Protophormia terraenovae. (n.d.). Retrieved September 04, 2020, from https://bugguide.net/node/view/862102 Byrd, J. -

Establishing Lower Developmental Thresholds for a Common Blowfly: for Use in Estimating Elapsed Time Since Death Using Entomologyical Methods

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Faculty Research, Scholarly, and Creative Activity 10-1-2011 Establishing Lower Developmental Thresholds for a Common BlowFly: For Use in Estimating Elapsed Time since Death Using Entomologyical Methods Gail S. Anderson Simon Fraser University Jodie-A. Warren Simon Fraser University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/faculty_rsca Part of the Entomology Commons, and the Forensic Science and Technology Commons Recommended Citation Gail S. Anderson and Jodie-A. Warren. "Establishing Lower Developmental Thresholds for a Common BlowFly: For Use in Estimating Elapsed Time since Death Using Entomologyical Methods" Defence R&D Canada – Centre for Security Science (2011). This Report is brought to you for free and open access by SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Research, Scholarly, and Creative Activity by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Establishing Lower Developmental Thresholds for a Common BlowFly For Use in Estimating Elapsed Time since Death Using Entomologyical Methods Gail S. Anderson Centre for Forensic Research School of Criminology Simon Fraser University Jodie-A. Warren Centre for Forensic Research School of Criminology Simon Fraser University Prepared By: Gail S. Anderson Simon Fraser University 888 University Drive Burnaby, B.C. Director, School of Criminology, Simon Fraser University Scientific Authority: John Evans, Project Manager, CPRC, 780-616-8308 The scientific or technical validity of this Contract Report is entirely the responsibility of the Contractor and the contents do not necessarily have the approval or endorsement of Defence R&D Canada. -

Blowfly Puparia in a Hermetic Container: Survival Under Decreasing Oxygen Conditions

Forensic Sci Med Pathol (2017) 13:328–335 DOI 10.1007/s12024-017-9892-3 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Blowfly puparia in a hermetic container: survival under decreasing oxygen conditions Anna Mądra-Bielewicz 1 & Katarzyna Frątczak-Łagiewska1,2 & Szymon Matuszewski1 Accepted: 26 May 2017 /Published online: 1 July 2017 # The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract Despite widely accepted standards for sampling Introduction and preservation of insect evidence, unrepresentative samples or improperly preserved evidence are encountered frequently The importance of insect evidence in criminal investigations in forensic investigations. Here, we report the results of labo- has increased substantially over recent decades [1]. However, ratory studies on the survival of Lucilia sericata and in practice it is extremely rare that a qualified forensic ento- Calliphora vomitoria (Diptera: Calliphoridae) intra-puparial mologist is present at the crime scene. Usually, insects are forms in hermetic containers, which were stimulated by a collected by crime scene technicians or medical examiners. recent case. It is demonstrated that the survival of blowfly Although there are widely accepted protocols for sampling intra-puparial forms inside airtight containers is dependent and preservation of insect evidence [1–5], unrepresentative on container volume, number of puparia inside, and their samples or improperly preserved evidence are encountered age. The survival in both species was found to increase with frequently in forensic investigations [1, 6]. an increase in the volume of air per 1 mg of puparium per day The blowfly puparium is an opaque, barrel-like structure; a of development in a hermetic container. Below 0.05 ml of air, prepupa, a pupa or a pharate adult (i.e. -

Test Key to British Blowflies (Calliphoridae) And

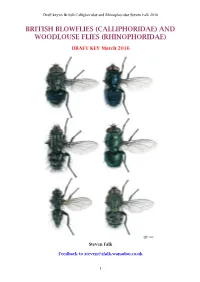

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016 BRITISH BLOWFLIES (CALLIPHORIDAE) AND WOODLOUSE FLIES (RHINOPHORIDAE) DRAFT KEY March 2016 Steven Falk Feedback to [email protected] 1 Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016 PREFACE This informal publication attempts to update the resources currently available for identifying the families Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae. Prior to this, British dipterists have struggled because unless you have a copy of the Fauna Ent. Scand. volume for blowflies (Rognes, 1991), you will have been largely reliant on Van Emden's 1954 RES Handbook, which does not include all the British species (notably the common Pollenia pediculata), has very outdated nomenclature, and very outdated classification - with several calliphorids and tachinids placed within the Rhinophoridae and Eurychaeta palpalis placed in the Sarcophagidae. As well as updating keys, I have also taken the opportunity to produce new species accounts which summarise what I know of each species and act as an invitation and challenge to others to update, correct or clarify what I have written. As a result of my recent experience of producing an attractive and fairly user-friendly new guide to British bees, I have tried to replicate that approach here, incorporating lots of photos and clear, conveniently positioned diagrams. Presentation of identification literature can have a big impact on the popularity of an insect group and the accuracy of the records that result. Calliphorids and rhinophorids are fascinating flies, sometimes of considerable economic and medicinal value and deserve to be well recorded. What is more, many gaps still remain in our knowledge. -

Key for Identification of European and Mediterranean Blowflies (Diptera, Calliphoridae) of Forensic Importance Adult Flies

Key for identification of European and Mediterranean blowflies (Diptera, Calliphoridae) of forensic importance Adult flies Krzysztof Szpila Nicolaus Copernicus University Institute of Ecology and Environmental Protection Department of Animal Ecology Key for identification of E&M blowflies, adults The list of European and Mediterranean blowflies of forensic importance Calliphora loewi Enderlein, 1903 Calliphora subalpina (Ringdahl, 1931) Calliphora vicina Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830 Calliphora vomitoria (Linnaeus, 1758) Cynomya mortuorum (Linnaeus, 1761) Chrysomya albiceps (Wiedemann, 1819) Chrysomya marginalis (Wiedemann, 1830) Chrysomya megacephala (Fabricius, 1794) Phormia regina (Meigen, 1826) Protophormia terraenovae (Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830) Lucilia ampullacea Villeneuve, 1922 Lucilia caesar (Linnaeus, 1758) Lucilia illustris (Meigen, 1826) Lucilia sericata (Meigen, 1826) Lucilia silvarum (Meigen, 1826) 2 Key for identification of E&M blowflies, adults Key 1. – stem-vein (Fig. 4) bare above . 2 – stem-vein haired above (Fig. 4) . 3 (Chrysomyinae) 2. – thorax non-metallic, dark (Figs 90-94); lower calypter with hairs above (Figs 7, 15) . 7 (Calliphorinae) – thorax bright green metallic (Figs 100-104); lower calypter bare above (Figs 8, 13, 14) . .11 (Luciliinae) 3. – genal dilation (Fig. 2) whitish or yellowish (Figs 10-11). 4 (Chrysomya spp.) – genal dilation (Fig. 2) dark (Fig. 12) . 6 4. – anterior wing margin darkened (Fig. 9), male genitalia on figs 52-55 . Chrysomya marginalis – anterior wing margin transparent (Fig. 1) . 5 5. – anterior thoracic spiracle yellow (Fig. 10), male genitalia on figs 48-51 . Chrysomya albiceps – anterior thoracic spiracle brown (Fig. 11), male genitalia on figs 56-59 . Chrysomya megacephala 6. – upper and lower calypters bright (Fig. 13), basicosta yellow (Fig. 21) . Phormia regina – upper and lower calypters dark brown (Fig. -

Study of Steroidogenesis in Pupae of the Forensically Important Blow Fly Protophormia Terraenovae (Robineau-Desvoidy) (Diptera

Forensic Science International 160 (2006) 27–34 www.elsevier.com/locate/forsciint Study of steroidogenesis in pupae of the forensically important blow fly Protophormia terraenovae (Robineau-Desvoidy) (Diptera: Calliphoridae) Emmanuel Gaudry a,*, Catherine Blais b,1, Annick Maria b, Chantal Dauphin-Villemant b a Institut de Recherche Criminelle de la Gendarmerie Nationale, 1 Boulevard The´ophile Sueur, F-93111 Rosny-Sous-Bois Cedex, France b Biogene`se des ste´roı¨des, FRE 2852, CNRS, Universite´ Pierre et Marie Curie, Case 29, 7 quai St. Bernard, F-75252 Paris Cedex 05, France Received 23 August 2004; accepted 20 June 2005 Available online 23 September 2005 Abstract Protophormia terraenovae is a forensically important fly whose development time is studied by forensic entomologists to establish the time elapsed since death (post-mortem interval, PMI). Quantity and nature of ecdysteroid hormones present in P. terraenovae pupae were analysed in order to determine if they could be correlated to the age of pupae found on corpses and thereby could give information on the PMI. Ecdysteroid levels were quantified during the pupal–adult development of synchronised animals using enzyme immunoassay (EIA), a sensitive method allowing acurate quantification in one pupa. Two types of pupae were compared: ‘‘fresh’’ pupae, kept frozen until analysis and ‘‘experimentally dried’’ pupae, which were left for several weeks at ambient temperature. A peak of ecdysteroids was detected between 36 and 96 h after pupariation in fresh animals. It was not observed in ‘‘experimentally dried’’ pupae. High-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) analyses combined with EIA showed that 20-hydroxyecdysone (20E) was the major free ecdysteroid at various pupal ages.