Classification As Culture: Types and Trajectories of Music Genres Author(S): Jennifer C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Concert Hall As a Medium of Musical Culture: the Technical Mediation of Listening in the 19Th Century

The Concert Hall as a Medium of Musical Culture: The Technical Mediation of Listening in the 19th Century by Darryl Mark Cressman M.A. (Communication), University of Windsor, 2004 B.A (Hons.), University of Windsor, 2002 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Communication Faculty of Communication, Art and Technology © Darryl Mark Cressman 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Darryl Mark Cressman Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) Title of Thesis: The Concert Hall as a Medium of Musical Culture: The Technical Mediation of Listening in the 19th Century Examining Committee: Chair: Martin Laba, Associate Professor Andrew Feenberg Senior Supervisor Professor Gary McCarron Supervisor Associate Professor Shane Gunster Supervisor Associate Professor Barry Truax Internal Examiner Professor School of Communication, Simon Fraser Universty Hans-Joachim Braun External Examiner Professor of Modern Social, Economic and Technical History Helmut-Schmidt University, Hamburg Date Defended: September 19, 2012 ii Partial Copyright License iii Abstract Taking the relationship -

Shoosh 800-900 Series Master Tracklist 800-977

SHOOSH CDs -- 800 and 900 Series www.opalnations.com CD # Track Title Artist Label / # Date 801 1 I need someone to stand by me Johnny Nash & Group ABC-Paramount 10212 1961 801 2 A thousand miles away Johnny Nash & Group ABC-Paramount 10212 1961 801 3 You don't own your love Nat Wright & Singers ABC-Paramount 10045 1959 801 4 Please come back Gary Warren & Group ABC-Paramount 9861 1957 801 5 Into each life some rain must fall Zilla & Jay ABC-Paramount 10558 1964 801 6 (I'm gonna) cry some time Hoagy Lands & Singers ABC-Paramount 10171 1961 801 7 Jealous love Bobby Lewis & Group ABC-Paramount 10592 1964 801 8 Nice guy Martha Jean Love & Group ABC-Paramount 10689 1965 801 9 Little by little Micki Marlo & Group ABC-Paramount 9762 1956 801 10 Why don't you fall in love Cozy Morley & Group ABC-Paramount 9811 1957 801 11 Forgive me, my love Sabby Lewis & the Vibra-Tones ABC-Paramount 9697 1956 801 12 Never love again Little Tommy & The Elgins ABC-Paramount 10358 1962 801 13 Confession of love Del-Vikings ABC-Paramount 10341 1962 801 14 My heart V-Eights ABC-Paramount 10629 1965 801 15 Uptown - Downtown Ronnie & The Hi-Lites ABC-Paramount 10685 1965 801 16 Bring back your heart Del-Vikings ABC-Paramount 10208 1961 801 17 Don't restrain me Joe Corvets ABC-Paramount 9891 1958 801 18 Traveler of love Ronnie Haig & Group ABC-Paramount 9912 1958 801 19 High school romance Ronnie & The Hi-Lites ABC-Paramount 10685 1965 801 20 I walk on Little Tommy & The Elgins ABC-Paramount 10358 1962 801 21 I found a girl Scott Stevens & The Cavaliers ABC-Paramount -

Settin' My Dial on the Radio

SETTIN ’ MY DIAL ON THE RADIO BOB DYLAN 2006 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES , NEW RELEASES , RECORDINGS & BOOKS . © 2010 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Settin’ My Dial On The Radio — Bob Dylan 2006 page 2 of 86 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................................................4 2 2006 AT A GLANCE ..............................................................................................................................................................4 3 THE 2006 CALENDAR ..........................................................................................................................................................4 4 NEW RELEASES AND RECORDINGS ..............................................................................................................................6 4.1 MODERN TIMES ................................................................................................................................................................6 4.2 BLUES ..............................................................................................................................................................................6 4.3 THEME TIME RADIO HOUR : BASEBALL ............................................................................................................................8 -

Why Am I Doing This?

LISTEN TO ME, BABY BOB DYLAN 2008 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES, NEW RELEASES, RECORDINGS & BOOKS. © 2011 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Listen To Me, Baby — Bob Dylan 2008 page 2 of 133 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2 2008 AT A GLANCE ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 3 THE 2008 CALENDAR ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 4 NEW RELEASES AND RECORDINGS ............................................................................................................................. 7 4.1 BOB DYLAN TRANSMISSIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 7 4.2 BOB DYLAN RE-TRANSMISSIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 7 4.3 BOB DYLAN LIVE TRANSMISSIONS ..................................................................................................................................... -

MU 116 Rock and Roll an Into Syllabus

Bellevue Community College Department of Music Rock and Roll an introduction MU 116 5 credits M-F room N 204 9:30 to 10:20 Mr. Mark H. Wilson office hours by appointment office E222 contact [email protected] or myspace.com/mhilliardwilson Required textbook Campbell, Michael. Brody, James. Rock and Roll an introduction, 2nd edition, Thomson Schirmer 2008 ISBN-13: 978-0-534-64295-2 Required Materials You will need a three ring binder to store printed web study guides and note paper for note taking in class. Course Objectives At the end of the quarter you should be able to: 1. Describe what created the conditions for the arrival of Rock and Roll 2. Aurally identify over a dozen of the various styles of music that made history over the last 50 years. 3. Describe the qualities that make the various styles of music distinct. 4. Identify the three basic elements that make up music Requirements of the Course 1. Reading assignments, 2. Bi-weekly quizzes (5) 3. One class presentation Week 1 March 31st to April 4th Mon. 31st Part 1 Chapter 1 It's only Rock and Roll pages 2 to 17 Tues. 1st Part 2 Chapter 2 Before Rock: Roots and antecedents, evolution and revolution pages 19 to 28 Wed. 2nd pages 28 to 38 Thurs. 3rd Chapter 3 A Revolutionary perspective pages 40 to 58 Fri. 4th pages 58 to 62 Week 2 April 7th to April 11th Mon. 7th Part 3 Becoming Rock: The Rock Era 1951 to 1964 Chapter 4 Rhythm and Blues pages 67 to 80 Tues.8th pages 81 to 98 Wed. -

Rap in the Context of African-American Cultural Memory Levern G

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Empowerment and Enslavement: Rap in the Context of African-American Cultural Memory Levern G. Rollins-Haynes Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES EMPOWERMENT AND ENSLAVEMENT: RAP IN THE CONTEXT OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN CULTURAL MEMORY By LEVERN G. ROLLINS-HAYNES A Dissertation submitted to the Interdisciplinary Program in the Humanities (IPH) in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Levern G. Rollins- Haynes defended on June 16, 2006 _____________________________________ Charles Brewer Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________________ Xiuwen Liu Outside Committee Member _____________________________________ Maricarmen Martinez Committee Member _____________________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member Approved: __________________________________________ David Johnson, Chair, Humanities Department __________________________________________ Joseph Travis, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii This dissertation is dedicated to my husband, Keith; my mother, Richardine; and my belated sister, Deloris. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Very special thanks and love to -

BC with Henri Chaix and His Orchestra

UPDATES TO VOLUME 2, BENNY CARTER: A LIFE IN AMERICAN MUSIC (2nd ed.) As a service to purchasers of the book, we will periodically update the material contained in Vol. 2. These updates follow the basic format used in the book’s Addendum section (pp. 809-822), and will include 1) any newly discovered sessions; 2) additional releases of previously listed sessions (by session number); 3) additional recordings of Carter’s arrangements and compositions (by title); 4) additional releases of previously listed recordings of Carter’s arrangements and compositions (by artist); 5) additional recorded tributes to Carter and entire albums of his music; and 6) additional awards received by Carter. We would welcome any new data in any of these areas. Readers may send information to Ed Berger ([email protected]). NOTE: These website additions do not include those listed in the book’s Addendum Section One (Instrumentalist): Additional Issues of Listed Sessions NOTE: All issues are CDs unless otherwise indicated. BC = Benny Carter Session #25 (Chocolate Dandies) Once Upon a Time: ASV 5450 (The Noble Art of Teddy Wilson) I Never Knew: Columbia River 220114 (Jazz on the Road) [2 CDs] Session #26 (BC) Blue Lou: Jazz After Hours 200006 (Best of Jazz Saxophone)[2 CDs]; ASV 5450 (The Noble Art of Teddy Wilson); Columbia River 120109 (Open Road Jazz); Columbia River 120063 (Best of Jazz Saxophone); Columbia River 220114 (Jazz on the Road) [2 CDs] Session #31 (Fletcher Henderson) Hotter Than ‘Ell: Properbox 37 (Ben Webster, Big Ben)[4 CDs] Session #33 (BC) -

ウィークエンド サンシャイン Playlist Archive Dj:ピーター・バラカン

ウィークエンド サンシャイン PLAYLIST ARCHIVE DJ:ピーター・バラカン 2017 年 12 月 2 日放送分 1. Getting Ready For Christmas Day / Paul Simon // So Beautiful Or So What 2. The Thoughts Of Mary Jane / Nick Drake // Time Of No Reply 3. Which Will / Lucinda Williams // This Sweet Old World 4. Six Blocks Away / Lucinda Williams // This Sweet Old World 5. I've Got To See You Again / Norah Jones // Recorded live at the Loreto Theater at the Sheen Center for Thought & Culture in New York City 6. Flipside / Norah Jones // Recorded live at the Loreto Theater at the Sheen Center for Thought & Culture in New York City 7. Yeh-Yeh! / Lambert, Hendricks & Bavan // Georgie Fame Heard Them Here First 8. Round Midnight / Miles Davis // 'Round About Midnight 9. My Back Pages / Keith Jarrett Trio // Somewhere Before 10. Sell Me A Diamond / David Crosby // Sky Trails 11. Amelia / David Crosby // Sky Trails 12. Shumba / Thomas Mapfumo // Shumba - Vital Hits Of Zimbabwe 13. Rachenitsa / Country For Syria 2017 年 12 月 9 日放送分 1. Hi Heel Sneakers (Saturday Club/1965) / Rolling Stones // On Air 2. Down The Road Apiece (Top Gear/1965) / Rolling Stones // On Air 3. The Last Time (Top Gear/1965) / Rolling Stones // On Air 4. Mona (Blues In Rhythm/1964) / Rolling Stones // On Air 5. Ain't That Loving You Baby (Rhythm And Blues - BBC World Service/1964) / Rolling Stones // On Air 6. Confessin’ The Blues (Joe Loss Pop Show/1964) / Rolling Stones // On Air 7. I Wanna Get Funky / Albert King // I Wanna Get Funky:The Best Of Albert King 8. -

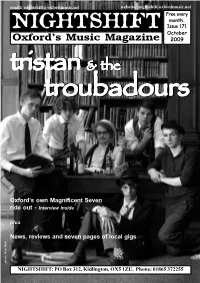

Issue 171.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 171 October Oxford’s Music Magazine 2009 tristantristantristantristan &&& thethethe troubadourstroubadourstroubadourstroubadourstroubadours Oxford’s own Magnificent Seven ride out - Interview inside plus News, reviews and seven pages of local gigs photo: Marc West photo: Marc NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net THIS MONTH’S OX4 FESTIVAL will feature a special Music Unconvention alongside its other attractions. The mini-convention, featuring a panel of local music people, will discuss, amongst other musical topics, the idea of keeping things local. OX4 takes place on Saturday 10th October at venues the length of Cowley Road, including the 02 Academy, the Bullingdon, East Oxford Community Centre, Baby Simple, Trees Lounge, Café Tarifa, Café Milano, the Brickworks and the Restore Garden Café. The all-day event has SWERVEDRIVER play their first Oxford gig in over a decade next been organised by Truck and local gig promoters You! Me! Dancing! Bands month. The one-time Oxford favourites, who relocated to London in the th already confirmed include hotly-tipped electro-pop outfit The Big Pink, early-90s, play at the O2 Academy on Thursday 26 November. The improvisational hardcore collective Action Beat and experimental hip hop band, who signed to Creation Records shortly after Ride in 1990, split in outfit Dälek, plus a host of local acts. Catweazle Club and the Oxford Folk 1999 but reformed in 2008, still fronted by Adam Franklin and Jimmy Festival will also be hosting acoustic music sessions. -

Queens Park Music Club

Alan Currall BBobob CareyCarey Grieve Grieve Brian Beadie Brian Beadie Clemens Wilhelm CDavidleme Hoylens Wilhelm DDavidavid MichaelHoyle Clarke DGavinavid MaitlandMichael Clarke GDouglasavin M aMorlanditland DEilidhoug lShortas Morland Queens Park Music Club EGayleilidh MiekleShort GHrafnhildurHalldayle Miekle órsdóttir Volume 1 : Kling Klang Jack Wrigley ó ó April 2014 HrafnhildurHalld rsd ttir JJanieack WNicollrigley Jon Burgerman Janie Nicoll Martin Herbert JMauriceon Burg Dohertyerman MMelissaartin H Canbazerbert MMichelleaurice Hannah Doherty MNeileli Clementsssa Canbaz MPennyichel Arcadele Hannah NRobeil ChurmClements PRoben nKennedyy Arcade RobRose Chu Ruanerm RoseStewart Ruane Home RobTom MasonKennedy Vernon and Burns Tom Mason Victoria Morton Stuart Home Vernon and Burns Victoria Morton Martin Herbert The Mic and Me I started publishing criticism in 1996, but I only When you are, as Walter Becker once learned how to write in a way that felt and still sang, on the balls of your ass, you need something feels like my writing in about 2002. There were to lift you and hip hop, for me, was it, even very a lot of contributing factors to this—having been mainstream rap: the vaulting self-confidence, unexpectedly bounced out of a dotcom job that had seesawing beat and herculean handclaps of previously meant I didn’t have to rely on freelancing Eminem’s armour-plated Til I Collapse, for example. for income, leaving London for a slower pace of A song like that says I am going to destroy life on the coast, and reading nonfiction writers everybody else. That’s the braggadocio that hip who taught me about voice and how to arrange hop has always thrived on, but it is laughable for a facts—but one of the main triggers, weirdly enough, critic to want to feel like that: that’s not, officially, was hip hop. -

The Golden Roach: Del Trap Al Rap Por Vía De Instagram

FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES, JURÍDICAS Y DE LA COMUNICACIÓN Grado Publicidad y Relaciones Públicas TRABAJO DE FIN DE GRADO The Golden Roach: del trap al rap por vía de Instagram Presentado por Diego Saludes Murciego Tutelado por Manuel Ángel Canga Sosa Segovia, 22 de junio de 2021 ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN…………………………………………………………………[p.4] MARCO TEÓRICO La industria cultural de masas y el movimiento urbano 1. La industria contracultural de masas ………………………………………....[p.6] 1.1. Cultura de masas y contracultura ...................................................... ...[p. 6] 1.2. La industria cultural y la homogeneización del arte ……….………….. [p. 9] 1.3. El dilema de la industria contracultural ..………………………...…….. [p. 11] 2. The realness: origen y superación del conflicto en EEUU……………….[p. 13] 2.1 El primer contacto del rap con el mainstream (1975-1980) ............... .[p. 13] 2.2 Creación de la industria musical del rap (1980 – 1995) .................... .[p. 16] 2.3 Desde la cultura underground hasta el surgimiento de los rapstars (1995 – Actualidad) ................................................................................................ .[p. 24] 3. El reflejo del movimiento en España ................................................... [p. 33] 3.1. El problema de la llegada del rap a España (1980 – 1995) ............. [p. 33] 3.2. La industria del rap en España (1995-2010) .................................... [p. 36] 3.3. La nueva generación y el cambio de paradigma (2010 – 2020).. ... [p. 40] PROYECTO PERSONAL CREATIVO LaChustaDeOro & Release -

We All Wanna Die, Too”: Emo Rap and Collective Despair in Adolescent America

“WE ALL WANNA DIE, TOO”: EMO RAP AND COLLECTIVE DESPAIR IN ADOLESCENT AMERICA A thesis submitted to the Kent State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for University Honors by Nina Palattella May 2020 Thesis written by Nina Palattella Approved by ________________________________________________________________, Advisor ______________________________________________, Chair, Department of English Accepted by ___________________________________________________, Dean, Honors College ii iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………………....v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS……………………………………………………….………vi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………….…1 II. “I WANT EVERYONE TO KNOW THAT I DON’T CARE”: CASE STUDY OF LIL PEEP……………………………………….….16 III. “BETTER OFF DYING”: DOES EMO RAP ASSUAGE OR AMPLIFY MENTAL HEALTH PROBLEMS?…………………………………… 26 IV. “XANS DON’T MAKE YOU”: EMO RAP’S GLORIFICATION OF, AND RECKONING WITH, DRUG ABUSE……………………………43 V. “WE ALL WANNA DIE, TOO”: HOW IS EMO RAP BRANDED, AND WHAT KIND OF LEGACY ARE ITS STARS LEAVING? ...………….60 VI. “WHEN I DIE YOU’LL LOVE ME”: WHAT DOES EMO RAP MEAN, AND WHAT DIRECTIONS MIGHT IT TAKE IN THE FUTURE? ….80 WORKS CITED …………………………………………………………………………89 iv LIST OF FIGURES Fig. 1. Lil Peep (Gustav Åhr) …………………………………………………17 Fig. 2. Still from “Awful Things” Music Video ………………………………21 Fig. 3. XXXTentacion (Jahseh Onfroy) ……………………………………….29 Fig. 4. Lil Xan (Diego Leanos) ……...………………………………………...36 Fig. 5. nothing,nowhere. (Joe Mulherin) ……………………………………...50 Fig. 6. Still from “Lean Wit Me” Music Video ……………………………….52 Fig. 7. Lil Uzi Vert (Symere Woods) ………………………………………….76 v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to offer my sincere thanks to everyone who made this thesis possible and who supported me as I completed it. I am especially grateful to Dr. Ryan Hediger for advising this project and encouraging me throughout the long process.