TOCC0392DIGIBKLT.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, Saturday, 20, May 1978, I.A O

Great Composers Concert IV I.A. O'Shauqhnessy Auditorium The College of St. Catherine, St. Paul Saturday, 20 May 1978 8 p.m. Lou Harrison, featured composer - The Dale Warland Singers, Dennis Russell Davies, piano now in their sixth season, Romuald Tecco, violin have become one of the fore- The Dale Warland Singers most choral groups in the Dale Warland, director central USA and are rapidly William McGlaughlin, Exxon/Arts Endowment attaining national and world- Conductor wide recognition. Comprising 38 singers from the St. Paul- Minneapolis area, they have esta blished an envia ble repu- tation for their musicality, versatility and diverse pro- gramming. The Dale Warland Suite for Violin, Piano and Small Orchestra Singers appear regularly Romuald Tecco, violin with the Saint Paul Chamber Dennis Russell Davies, piano Orchestra and the Minnesota Opera Company. They give concerts throughout the Mid- west and broadcast regularly Suite from Marriage at the Eiffel Tower over public radio. At the invi- tation of the Swedish govern- ment.JheSingers toured INTERMISSION Sweden and-Norway in July 1977. They haverecorded incidental music for two Ear- ~ radio drama productions Mass to Saint Anthony ~ " ational Public Radio and .. ave made two recordings of 20th-century choral music. The choir has given a perfor- mance in honor of Sweden's King Carl Gustav, as well as concerts with tenor Ernst Haefliger, the American Brass Quintet, the Minnesota Orchestra and for the Minne- sota Bicentennial Commission. Lou Harrison (b. Portland, Oregon, 14 May 1917) Lou Harr-ison was raised in Oregon and California. He spent a decade in New York studying with Henry Cowell, Arnold Schoenberg and Virgil Thomson. -

Gloucester Cathedral Lay Clerks

GLOUCESTER CATHEDRAL ORGAN SCHOLARSHIP The Dean & Chapter of Gloucester Cathedral annually seek to appoint an organ scholar for each academic year. He/She will play a key role in the Cathedral music department, working closely with Adrian Partington (Director of Music), Jonathan Hope (Assistant Director of Music), Nia Llewelyn Jones (Singing Development Leader) and Helen Sims (Music Department Manager). The organ scholarship is open to recent graduates or to gap-year applicants of exceptional ability. Duties The organ scholar plays for Evensong every Tuesday, and in addition plays the organ or directs the choirs as necessary when the DoM or the ADoM is away. He/She will also play for many of the special services which take place in the Cathedral, for which additional fees are paid (see remuneration details below). The organ scholar is fully involved with the training of choristers and probationers and the teaching of theory and general musicianship. They will also be expected to help with the general administration of the music department, attending a weekly meeting and assisting other members of the department in the music office. Gloucester Cathedral Choir Today’s choir is the successor to the boys and monks of the Benedictine Abbey of St Peter, who sang for daily worship nine centuries ago. The choir of today stems from that established by Henry VIII in 1539, consisting of 18 choristers (who receive generous scholarships to attend the neighbouring King’s School), 12 lay clerks and choral scholars. The choir plays a major part in the internationally renowned Three Choirs Festival, the world’s oldest Music Festival, which dates back to 1715. -

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL Recordings of the Year 2019

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL Recordings Of The Year 2019 This is the seventeenth year that MusicWeb International has asked its reviewing team to nominate their recordings of the year. Reviewers are not restricted to discs they had reviewed, but the choices must have been reviewed on MWI in the last 12 months (December 2018-November 2019). The 128 selections have come from 27 members of the team and 65 different labels, the choices reflecting as usual, the great diversity of music and sources; I say that every year, but still the spread of choices surprises and pleases me. Of the selections, one has received three nominations: An English Coronation on Signum Classics and ten have received two nominations: Gounod’s Faust on Bru Zane Matthias Goerne’s Schumann Lieder on Harmonia Mundi Prokofiev’s Romeo & Juliet choreographed by John Cranko on C Major Marx’s Herbstymphonie on CPO Weinberg symphonies on DG Shostakovich piano works on Hyperion Late Beethoven sonatas on Hyperion Korngold orchestral works on Chandos Coates orchestral works on Chandos Music connected to Leonardo da Vinci on Alpha Hyperion was this year’s leading label with nine nominations, just ahead of C Major with eight. MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL RECORDING OF THE YEAR In this twelve month period, we published more than 2300 reviews. There is no easy or entirely satisfactory way of choosing one above all others as our Recording of the Year, but this year one recording in particular put itself forward as the obvious candidate. An English Coronation 1902-1953 Simon Russell Beale, Rowan Pierce, Matthew Martin, Gabrieli Consort; Gabrieli Roar; Gabrieli Players; Chetham’s Symphonic Brass Ensemble/Paul McCreesh rec. -

Hifi /Stereo Review of April 1968

fulStereo Review APRIL 1968 60 CENTS NINE SOLUTIONS TO THE STEREO -INSTALLATION PROBLEM WHICH RECORDINGS FOR A DESERT -ISLAND DISCOGRAPHY? *AMERICAN COMPOSERS SERIES: WALLINGFORD RIEGGER * Hifi/StereoReview APRIL 1968 VOLUME 20 NUMBER 4 THE MUSIC GIACOMO MEYERBEER'S OPERA OF THE SEVEN STARS A report on Les Huguenots and Wagner inLondon HENRY PLEASANTS 48 THE BASIC REPERTOIRE Beethoven's Symphony No. 1, in C Major MARTIN BOOKSPA 53 WALLINGFORD RI EGGER A true original among the Great American Composers RICHARD FRANKO GOLDMAN 57 DESERT -ISLAND DISCOGRAPHY One man's real -life answers to a popular speculation 68 THE BAROQUE MADE PLAIN A new Vanguard release demonstrates Baroque ornamentation IGOR KIPNIS 106 THE EQUIPMENT NEW PRODUCTS A roundup of the latest high-fidelity equipment 22 HI-FI Q & A Answers to your technical questions LARRY KLEIN 28 AUDIO BASICS Specifications XX: Separation HANSH. FANTEL 34 TECHNICAL TALK ProductEvaluation;Hirsch -HoucklaboratoryreportsontheA ltec711stereo FM receiver, the Switchcraft 307TR studio mixer, and the Wollensah 5800 tape re- corder JULIAN D. HIRSCH 37 STEREO INGENUITY Clever and inexpensive component cabinets-a photo portfolio LARRY KLEIN 70 TAPE HORIZONS Tape and Home Movies DRUMMOND MCINNIS 127 THE REVIEWS BEST RECORDINGS OF THE MONTH 75 CLASSICAL 81 ENTERTAINMENT 109 STEREO TAPE 123 THE REGULARS EDITORIALLY SPEAKING WII.LIAM ANDERSON 4 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 6 GOING ON RECORD JAMESGOODFRIEND 44 ADVERTISERS' INDEX; PRODUCT INDEX 130 COVER: .1. B. S. CHARDIN: STILL LIFE WITH HURDY-GURDY: PHOTO BY PETER ADEI.IIERG. EURDPF.AN ART COLOR SLIDE COMPANY, NEW YORK Copyright 1968 by Ziff -Davis Publishing Company. All rights reserved. -

Kenneth Woods - Conductor

Kenneth Woods - Conductor - Contents “A symphonic conductor of stature” Gramophone Biography Resumé “A conductor with Discography true vision and purpose” Acclaim Peter Oundjian References Music Director, Toronto Symphony Contact “brimming with personality, affection Management, engagements and freshly imagined drama” ABMC Productions International Washington Post Matthew Peters-Managing Director (UK and Europe) [email protected] “Woods proves in this recording to be +44 7726 661 659 a front rank conductor” Sativa Saposnek- Director of North Audiophile Audition American Operations (USA, Canada, Mexico and South America) [email protected] + 1 978.701.4914 “In 20 years of being a music critic, I have never written a story like this Special Projects and Media Relations one about Pendleton's symphony Melanne Mueller pulling out all the stops to play MusicCo International, Ltd. [email protected] Mahler's First Symphony after a UK +44 (0) 20 8542 4866 devastating fire ... The OES under USA +1 917 907 2785 Kenneth Woods, looking like a 103 Churston Drive Morden, Surrey SM4 4JE younger, dark haired William Hurt, Skype melanne4 gives Mahler the ride of his life.” The Oregonian 1 Kenneth Woods, conductor www.kennethwoods.net Kenneth Woods, conductor Biography Hailed by the Washington Post as a “true star” of the podium, conductor, rock guitarist, author and cellist Kenneth Woods has worked with many orchestras of international distinction including the National Symphony Orchestra, Royal Philharmonic, English Chamber Orchestra, Cincinnati Symphony, BBC National Orchestra of Wales, Budapest Festival Orchestra and State of Mexico Symphony Orchestra. He has also appeared on the stages of some of the world’s leading music festivals such as Aspen and Lucerne. -

MAHLERFEST XXXIV the RETURN Decadence & Debauchery | Premieres Mahler’S Fifth Symphony | 1920S: ARTISTIC DIRECTOR

August 24–28, 2021 Boulder, CO Kenneth Woods Artistic Director SAVE THE DATE MAHLERFEST XXXV May 17–22, 2022 * Gustav Mahler Symphony No. 2 in C Minor Boulder Concert Chorale Stacey Rishoi Mezzo-soprano April Fredrick Soprano Richard Wagner Die Walküre (The Valkyrie), Act One Stacey Rishoi Mezzo-soprano Brennen Guillory Tenor Matthew Sharp Bass-baritone * All programming and artists subject to change KENNETH WOODS Mahler’s First | Mahler’s Musical Heirs Symphony | Mahler and Beethoven MAHLERFEST.ORG MAHLERFEST XXXIV THE RETURN Decadence & Debauchery | Premieres Mahler’s Fifth Symphony | 1920s: ARTISTIC DIRECTOR 1 MAHLERFEST XXXIV FESTIVAL WEEK TUESDAY, AUGUST 24, 7 PM | Chamber Concert | Dairy Arts Center, 2590 Walnut Street Page 6 WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 25, 4 PM | Jason Starr Films | Boedecker Theater, Dairy Arts Center Page 9 THURSDAY, AUGUST 26, 4 PM | Chamber Concert | The Academy, 970 Aurora Avenue Page 10 FRIDAY, AUGUST 27, 8 PM | Chamber Orchestra Concert | Boulder Bandshell, 1212 Canyon Boulevard Page 13 SATURDAY, AUGUST 28, 9:30 AM–3:30 PM | Symposium | License No. 1 (under the Hotel Boulderado) Page 16 SATURDAY, AUGUST 28, 7 PM | Orchestral Concert Festival Finale | Macky Auditorium, CU Boulder Page 17 Pre-concert Lecture by Kenneth Woods at 6 PM ALL WEEK | Open Rehearsals, Dinners, and Other Events See full schedule online PRESIDENT’S GREETING elcome to MahlerFest XXXIV – What a year it’s been! We are back and looking to the future with great excitement and hope. I would like to thank our dedicated and gifted MahlerFest orchestra and festival musicians, our generous supporters, and our wonderful audience. I also want to acknowledge the immense contributions of Executive Director Ethan Hecht and Maestro Kenneth Woods that not only make this festival Wpossible but also facilitate its evolution. -

Contents Price Code an Introduction to Chandos

CONTENTS AN INTRODUCTION TO CHANDOS RECORDS An Introduction to Chandos Records ... ...2 Harpsichord ... ......................................................... .269 A-Z CD listing by composer ... .5 Guitar ... ..........................................................................271 Chandos Records was founded in 1979 and quickly established itself as one of the world’s leading independent classical labels. The company records all over Collections: Woodwind ... ............................................................ .273 the world and markets its recordings from offices and studios in Colchester, Military ... ...208 Violin ... ...........................................................................277 England. It is distributed worldwide to over forty countries as well as online from Brass ... ..212 Christmas... ........................................................ ..279 its own website and other online suppliers. Concert Band... ..229 Light Music... ..................................................... ...281 Opera in English ... ...231 Various Popular Light... ......................................... ..283 The company has championed rare and neglected repertoire, filling in many Orchestral ... .239 Compilations ... ...................................................... ...287 gaps in the record catalogues. Initially focussing on British composers (Alwyn, Bax, Bliss, Dyson, Moeran, Rubbra et al.), it subsequently embraced a much Chamber ... ...245 Conductor Index ... ............................................... .296 -

Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan a Dissertation Submitted

Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: David Alexander Rahbee, Chair JoAnn Taricani Timothy Salzman Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Music ©Copyright 2016 Tigran Arakelyan University of Washington Abstract Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. David Alexander Rahbee School of Music The goal of this dissertation is to make available all relevant information about orchestral music by Armenian composers—including composers of Armenian descent—as well as the history pertaining to these composers and their works. This dissertation will serve as a unifying element in bringing the Armenians in the diaspora and in the homeland together through the power of music. The information collected for each piece includes instrumentation, duration, publisher information, and other details. This research will be beneficial for music students, conductors, orchestra managers, festival organizers, cultural event planning and those studying the influences of Armenian folk music in orchestral writing. It is especially intended to be useful in searching for music by Armenian composers for thematic and cultural programing, as it should aid in the acquisition of parts from publishers. In the early part of the 20th century, Armenian people were oppressed by the Ottoman government and a mass genocide against Armenians occurred. Many Armenians fled -

A Collection of Stan Ruttenberg's Reviews of Mahler Recordings From

A collection of Stan Ruttenberg’s Reviews of Mahler Recordings from the Archives Of the Colorado MahlerFest (Symphonies 3 through 7 and Kindertotenlieder) Colorado MahlerFest XIII Recordings of the Mahler Third Symphony Of the fifty recordings listed in Peter Fülöp’s monumental discography (up to 1955, and many more have been added since then), I review here fifteen at my disposal, leaving out two by Boulez and one by Scherchen as not as worthy as the others. All of these fifteen are recommendable, all with fine points, all with some or more weaknesses. I cannot rank them in any numerical order, but I can say that there are four which I would rather hear more than the others — my desert island choices. I am glad to have the others for their own particular merits. Getting ready for MFest XIII we discovered that the matter of score versions and parts is complex. I use the Dover score, no date but attributed to Universal Edition; my guess this is an early version. The Kalmus edition is copied from who knows which published version. Then there is the “Critical Edition,” prepared by the Mahler Gesellschaft, Vienna. I can find two major discrepancies between the Dover/Universal and the Critical (I) the lack of horns at RN25-5, doubling the string riff and (ii) only two harp glissandi at the middle of RN28, whereas the Critical has three. Our first horn found another. Both the Dover and Critical have the horn doublings, written ff at RN 67, but only a few conductors observe them. -

SPECIAL ORGAN RECITALS 2016 350Th Anniversary Celebration Series

SPECIAL ORGAN RECITALS 2016 350th Anniversary Celebration Series Wednesdays at 7:30pm The Organ of Gloucester Cathedral Thomas Harris 1666; Henry Willis 1847; Harrison & Harrison 1920 Hill, Norman & Beard 1971; Nicholson & Co. 1999, 2010 CHOIR SWELL PEDAL Stopped Diapason 8 Céleste 8 Flute 16 Principal 4 Salicional 8 Principal 16 Chimney Flute 4 Chimney Flute 8 Sub Bass 16 Fifteenth 2 Principal 4 Quint 102/3 Nazard 11/3 Open Flute 4 Octave 8 Sesquialtera II Nazard 22/3 Stopped Flute 8 Mixture III Gemshorn 2 Tierce 62/5 Cremona 8 Tierce 13/5 Septième 44/7 Trompette Harmonique 8 Mixture IV Choral Bass 4 Great Reeds on Choir Cimbel III Open Flute 2 Tremulant Fagotto 16 Mixture IV Trumpet 8 Bombarde 32 GREAT (* speaking west) Hautboy 8 Bombarde 16 Gedecktpommer 16 Vox Humana 8 Trumpet 8 Open Diapason 8 Sub-Octave coupler Shawm 4 Open Diapason* 8 Tremulant Bourdon 8 COUPLERS Spitz Flute* 8 WEST POSITIVE (Manual IV) Swell to Great** Octave 4 Gedecktpommer 8 Choir to Great* Prestant* 4 Spitz Flute 4 West Positive to Great* Stopped Flute 4 Nazard 22/3 Swell to Choir Flageolet 2 Doublette 2 West Positive to Choir Quartane* II Tierce 13/5 Great to Pedal** Mixture IV-VI Septième 11/7 Swell to Pedal* Cornet IV Cimbel III Choir to Pedal* Posaune* 16 Trompette Harmonique ` 8 Manual IV to Pedal* Trumpet* 8 Tremulant Combination Couplers: Clarion* 4 West Great Flues on IV Great and Pedal combined West Great Flues Sub-Octave Great Reeds on IV Generals on Swell toe pistons COMPASS ACCESSORIES Manuals C-A = 58 notes Reversible thumb pistons to stops Six thumb pistons to Choir Pedals CC-G = 32 notes marked* Eight toe pistons to Pedal Reversible thumb and toe pistons to Eight toe pistons to Swell Two mechanical swell pedals to East stops marked** Eight General thumb pistons and West Swell shutters Four stepper pistons (2+ and 2-) General Cancel Four thumb pistons to W. -

Program Book

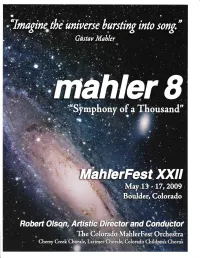

MahlerFest XXII Schedule of Events TERESE STEWART MEMORIAL CHAMBER CONCERT Wednesday, May 13, 2009, 7 :00 PM Boulder Public Llbrary Canyon Theater, 9th & Canyon Friday,May 15,7:30 PM Rocky Mountain Center for Musical Arts, 200 E. Baseline Rd., Lafayette Programr Musical Sertings of Passages from Goeth es Faust, by Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, Liszt, Mussorgsky, and Lili Boulanger Karherine Montgomery, mezzo soprano; Joel Burcham, tenor; Patrick Mason, baritone; Christopher Zemliauskas, piano SYMPOSIUM Saturday, May 76,9100 AM - 3:30 PM Chamber Hall, Room C-799,Imig Music Building (CU-Boulder) l Marilyn McCoy, Boston, Massachusetts "Coaxing ,,'. the Universe to Resound and Ring: .:::::,::::::::. A Look at Some Climactic Moments from Mahler's Eighth Symphonf" , ,,,,,::r,,,i Robert Olson, Artistic Director, Colorado MahlerFest 'A Conductor's Perspective on Mahlers Eighth Symphony" : Jane K. Brown, University of Washington (Seattle) "Ever Onward: Goethes Fdusr around 1900" Stephen E. Hefing, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio :::' ,,'Accendelumensensibus,lAGreatBearerofJoy,AGifttotheNation,, SYMPHONY CONCERIS Saturday, May L6 & Sunday, May 77 ,2009 Macky Auditorium, CU Campus, Boulder The Colorado MahlerFest Orchestra, Robert Olson, conductor See page 2 for details. Fundingfor MahlerFest XXII has been prouided in part b1 grants f'on The Sciendfic and Cultural Facilities District, Tier III, administered by the Bouller Counry Commissioners; Avenir Foundation; Dietrich Foundation of Philadelphia; Boulder Public Library Foundation; -

The Music of Alan Hovhaness

THE MUSIC OF ALAN HOVHANESS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts by Niccolo Davis Athens May, 2016 ii © 2016 Niccolo Davis Athens iii ABSTRACT The Music of Alan Hovhaness Niccolo Davis Athens, DMA Cornell University 2016 This dissertation is an attempt to redress the dearth of serious scholarship on the music of the American composer Alan Hovhaness (1911-2000). As Hovhaness’s catalogue is one of the largest of any 20 th -century composer, this dissertation sets out to provide as complete a picture as possible of his output without discussing all six-hundred-plus works. This involves giving a comprehensive account of the important elements of Hovhaness’s musical language, placing his work in the context of 20 th -century American concert music at large, and exploring the major issues surrounding his music and its reception, notably his engagement with various non- Western musical traditions and his resistance to the prevailing modernist trends of his time. An integrated biographical element runs throughout, intended to provide a foundation for the discussion of Hovhaness’s music. The first chapter of this dissertation is concerned with an examination of Hovhaness’s surviving juvenilia, after which it is divided according to the following style periods: early, Armenian, middle, “Eastern,” and late. An additional chapter dealing with Hovhaness’s experiences at Tanglewood in 1942 and what they reveal about his artistic values appears between the chapters on the music of the early and Armenian periods.