Hifi /Stereo Review of April 1968

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wallingford Riegger

WALLINGFORD RIEGGER: Romanza — Music for Orchestra Alfredo Antonini conducting the Orchestra of the “Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia-Roma” Dance Rhythms Alfredo Antonini conducting the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra THIS RELEASE is but further evidence of the growing and gratifying tendency of recent years to recognize Wallingford Riegger as one of the leading and most influential figures in twentieth century American composition, in fact as the dean of American composers. Herbert Elwell, music critic of the Cleveland Plain Dealer, said it in April, 1956: “I am coming more and more to the conclusion that it is Riegger who has been the real leader and pathfinder in contemporary American music . not only a master of his craft but in some ways a prophet and a seer.” In the same month, in Musical America, Robert Sabin wrote: “I firmly believe that his work will outlast that of many an American composer who has enjoyed far greater momentary fame.” Riegger was born in Albany, Georgia, on April 29, 1885. Both his parents were amateur musicians and were determined to encourage their children in musical study. When the family moved to New York in 1900, the young Wallingford was enrolled at the Institute of Musical Art where he studied the cello and composition. Graduating from there in 1907 Riegger then went to Germany to study at the Hochschule für Musik in Berlin with Max Bruch. In 1915-1916 he conducted opera in Würzburg and Königsberg and the following season he led the Blüthner Orchestra in Berlin. Since his return to the United States in 1917, he has been active in many phases of our musical life. -

The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, Saturday, 20, May 1978, I.A O

Great Composers Concert IV I.A. O'Shauqhnessy Auditorium The College of St. Catherine, St. Paul Saturday, 20 May 1978 8 p.m. Lou Harrison, featured composer - The Dale Warland Singers, Dennis Russell Davies, piano now in their sixth season, Romuald Tecco, violin have become one of the fore- The Dale Warland Singers most choral groups in the Dale Warland, director central USA and are rapidly William McGlaughlin, Exxon/Arts Endowment attaining national and world- Conductor wide recognition. Comprising 38 singers from the St. Paul- Minneapolis area, they have esta blished an envia ble repu- tation for their musicality, versatility and diverse pro- gramming. The Dale Warland Suite for Violin, Piano and Small Orchestra Singers appear regularly Romuald Tecco, violin with the Saint Paul Chamber Dennis Russell Davies, piano Orchestra and the Minnesota Opera Company. They give concerts throughout the Mid- west and broadcast regularly Suite from Marriage at the Eiffel Tower over public radio. At the invi- tation of the Swedish govern- ment.JheSingers toured INTERMISSION Sweden and-Norway in July 1977. They haverecorded incidental music for two Ear- ~ radio drama productions Mass to Saint Anthony ~ " ational Public Radio and .. ave made two recordings of 20th-century choral music. The choir has given a perfor- mance in honor of Sweden's King Carl Gustav, as well as concerts with tenor Ernst Haefliger, the American Brass Quintet, the Minnesota Orchestra and for the Minne- sota Bicentennial Commission. Lou Harrison (b. Portland, Oregon, 14 May 1917) Lou Harr-ison was raised in Oregon and California. He spent a decade in New York studying with Henry Cowell, Arnold Schoenberg and Virgil Thomson. -

Collective Difference: the Pan-American Association of Composers and Pan- American Ideology in Music, 1925-1945 Stephanie N

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Collective Difference: The Pan-American Association of Composers and Pan- American Ideology in Music, 1925-1945 Stephanie N. Stallings Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC COLLECTIVE DIFFERENCE: THE PAN-AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF COMPOSERS AND PAN-AMERICAN IDEOLOGY IN MUSIC, 1925-1945 By STEPHANIE N. STALLINGS A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2009 Copyright © 2009 Stephanie N. Stallings All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Stephanie N. Stallings defended on April 20, 2009. ______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Dissertation ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee Member ______________________________ Charles Brewer Committee Member ______________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my warmest thanks to my dissertation advisor, Denise Von Glahn. Without her excellent guidance, steadfast moral support, thoughtfulness, and creativity, this dissertation never would have come to fruition. I am also grateful to the rest of my dissertation committee, Charles Brewer, Evan Jones, and Douglass Seaton, for their wisdom. Similarly, each member of the Musicology faculty at Florida State University has provided me with a different model for scholarly excellence in “capital M Musicology.” The FSU Society for Musicology has been a wonderful support system throughout my tenure at Florida State. -

Schenker's First “Americanization”: George Wedge, the Institute of Musical Art, And

Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic Volume 4 Issue 1 Article 7 January 2011 Schenker’s First “Americanization”: George Wedge, the Institute of Musical Art, and the “Appreciation Racket” David Carson Berry [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Berry, David Carson (2011) "Schenker’s First “Americanization”: George Wedge, the Institute of Musical Art, and the “Appreciation Racket”," Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic: Vol. 4 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut/vol4/iss1/7 This A Music-Theoretical Matrix: Essays in Honor of Allen Forte (Part III), edited by David Carson Berry is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut. SCHENKER’S FIRST “AMERICANIZATION”: GEORGE WEDGE, THE INSTITUTE OF MUSICAL ART, AND THE “APPRECIATION RACKET” DAVID CARSON BERRY quarter of a century ago, William Rothstein first employed a now common phrase when A he spoke of the “Americanization of Schenker”—that is, the accommodation that had to be made to bring Schenker’s ideas into the American academy, a process that involved ex- punging (or at least reconstituting) “those elements of Schenker’s thought [that clashed] most spectacularly with the American mind.”1 Rothstein focused mainly on émigrés displaced by the Second World War (e.g., Oswald Jonas, Ernst Oster, and Felix Salzer), and on Americans a generation younger (e.g., Milton Babbitt and Allen Forte). -

A List of Symphonies the First Seven: 1

A List of Symphonies The First Seven: 1. Anton Webern, Symphonie, Op. 21 2. Artur Schnabel, Symphony No. 2 3. Fartein Valen, Symphony No. 4 4. Humphrey Searle, Symphony No. 5 5. Roger Sessions, Symphony No. 8 6. Arnold Schoenberg, Kammersymphonie Nr. 2 op. 38b 7. Arnold Schoenberg, Kammersymphonie Nr. 1 op. 9b The Others: Stefan Wolpe, Symphony No. 1 Matthijs Vermeulen, Symphony No. 6 (“Les Minutes heureuses”) Allan Pettersson, Symphony No. 4, Symphony No. 5, Symphony No. 6, Symphony No. 8, Symphony No. 13 Wallingford Riegger, Symphony No. 4, Symphony No. 3 Fartein Valen, Symphony No. 1, Symphony No. 2 Alain Bancquart, Symphonie n° 1, Symphonie n° 5 (“Partage de midi” de Paul Claudel) Hanns Eisler, Kammer-Sinfonie Günter Kochan, Sinfonie Nr.3 (In Memoriam Hanns Eisler), Sinfonie Nr.4 Ross Lee Finney, Symphony No. 3, Symphony No. 2 Darius Milhaud, Symphony No. 8 (“Rhodanienne”, Op. 362: Avec mystère et violence) Gian Francesco Malipiero, Symphony No. 9 ("dell'ahimé"), Symphony No. 10 ("Atropo"), & Symphony No. 11 ("Della Cornamuse") Roberto Gerhard, Symphony No. 1, No. 2 ("Metamorphoses") & No. 4 (“New York”) E.J. Moeran, Symphony in g minor Roger Sessions, Symphony No. 4, Symphony No. 5, Symphony No. 9 Edison Denisov, Symphony No. 1, Symphony No. 2; Chamber Symphony No. 1 (1982) Artur Schnabel, Symphony No. 1 Sir Edward Elgar, Symphony No. 2, Symphony No. 1 Frank Corcoran, Symphony No. 3, Symphony No. 2 Ernst Krenek, Symphony No. 5 Erwin Schulhoff, Symphony No. 1 Gerd Domhardt, Sinfonie Nr.2 Alvin Etler, Symphony No. 1 Meyer Kupferman, Symphony No. 4 Humphrey Searle, Symphony No. -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries. -

Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan a Dissertation Submitted

Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: David Alexander Rahbee, Chair JoAnn Taricani Timothy Salzman Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Music ©Copyright 2016 Tigran Arakelyan University of Washington Abstract Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. David Alexander Rahbee School of Music The goal of this dissertation is to make available all relevant information about orchestral music by Armenian composers—including composers of Armenian descent—as well as the history pertaining to these composers and their works. This dissertation will serve as a unifying element in bringing the Armenians in the diaspora and in the homeland together through the power of music. The information collected for each piece includes instrumentation, duration, publisher information, and other details. This research will be beneficial for music students, conductors, orchestra managers, festival organizers, cultural event planning and those studying the influences of Armenian folk music in orchestral writing. It is especially intended to be useful in searching for music by Armenian composers for thematic and cultural programing, as it should aid in the acquisition of parts from publishers. In the early part of the 20th century, Armenian people were oppressed by the Ottoman government and a mass genocide against Armenians occurred. Many Armenians fled -

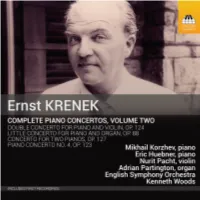

TOCC0392DIGIBKLT.Pdf

ERNST KRENEK: COMPLETE PIANO CONCERTOS, VOLUME TWO – 1. THE MUSIC-HISTORIAN’S PERSPECTIVE by Peter Tregear Ernst Krenek’s reputation as a ‘one-man history of twentieth century music’ is nothing if not well deserved. Over nearly eight decades of creative life he was not only to witness but also to contribute to most of the formative art-music movements of the age. It may come as a surprise, then, to find that the concertos on this second album are quite similar in style – until one realises that all four works were composed in the ten or so years following his arrival in America, when he was coming to terms with the likelihood of an indefinite period of exile from Europe. Te prospect did not rest easy with him, not least because, as he later observed, ‘in America, I am a composer-in-residence since I am not American-born, while in Europe, I am a composer-in-absence’.1 Here he would also no longer be able to support himself through composing alone. Instead, like so many of Europe’s cultural and scientific elite who also had had to flee Nazi Germany in fear of their lives, a career in university teaching beckoned. Now in relative isolation from compositional developments in Europe and elsewhere, and faced with the necessity of forging what was essentially a new career as he approached middle age, a degree of consolidation and stock-taking in his compositional outlook was perhaps inevitable. In February 1939 Krenek commenced a two-year contract as a professor in music at Vassar College, a liberal-arts College in up-state New York, which then was followed by an offer of a Chair in Music at Hamline University in Saint Paul, Minnesota. -

The Music of Alan Hovhaness

THE MUSIC OF ALAN HOVHANESS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts by Niccolo Davis Athens May, 2016 ii © 2016 Niccolo Davis Athens iii ABSTRACT The Music of Alan Hovhaness Niccolo Davis Athens, DMA Cornell University 2016 This dissertation is an attempt to redress the dearth of serious scholarship on the music of the American composer Alan Hovhaness (1911-2000). As Hovhaness’s catalogue is one of the largest of any 20 th -century composer, this dissertation sets out to provide as complete a picture as possible of his output without discussing all six-hundred-plus works. This involves giving a comprehensive account of the important elements of Hovhaness’s musical language, placing his work in the context of 20 th -century American concert music at large, and exploring the major issues surrounding his music and its reception, notably his engagement with various non- Western musical traditions and his resistance to the prevailing modernist trends of his time. An integrated biographical element runs throughout, intended to provide a foundation for the discussion of Hovhaness’s music. The first chapter of this dissertation is concerned with an examination of Hovhaness’s surviving juvenilia, after which it is divided according to the following style periods: early, Armenian, middle, “Eastern,” and late. An additional chapter dealing with Hovhaness’s experiences at Tanglewood in 1942 and what they reveal about his artistic values appears between the chapters on the music of the early and Armenian periods. -

Instead Draws Upon a Much More Generic Sort of Free-Jazz Tenor Saxophone Musical Vocabulary

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. GEORGE AVAKIAN NEA JAZZ MASTER (2010) Interviewee: George Avakian (March 15, 1919 – November 22, 2017) Interviewer: Ann Sneed with recording engineer Julie Burstein Date: September 28, 1993 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Description: Transcript, 112 pp. Sneed: I’m Ann Sneed. We are in Riverdale. We’re interviewing George Avakian. There’s so many things to say about you, I’m just going to say George Avakian and ask you first, why jazz? Avakian: I think it happened because I was born abroad, and among the things that came into my consciousness as I was growing up was American popular music, and then it drifted in the direction of jazz through popular dance bands, such as the Casa Loma Orchestra, which I heard about through the guys who were hanging around the home of our neighbor at Greenwood Lake, which is where we went in the summers. We had a house on the lake. Our next-door neighbors had two daughters, one of whom was my age and very pretty, Dorothy Caulfield, who incidentally is responsible for Holden Caulfield’s last name, because J. D. Salinger got to know her and was very fond of her, named Holden after her family name. These boys came from the Teaneck area of New Jersey. So it was a short drive to Greenwood Lake on a straight line between New York and New Jersey. They had a dance band, the usual nine pieces: three brass, three saxophones, three rhythm. -

The Harold E. Johnson Jean Sibelius Collection at Butler University

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Special Collections Bibliographies University Special Collections 1993 The aH rold E. Johnson Jean Sibelius Collection at Butler University: A Complete Catalogue (1993) Gisela S. Terrell Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.butler.edu/scbib Part of the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Terrell, Gisela S., "The aH rold E. Johnson Jean Sibelius Collection at Butler University: A Complete Catalogue (1993)" (1993). Special Collections Bibliographies. Book 1. http://digitalcommons.butler.edu/scbib/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Special Collections at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Collections Bibliographies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ^ IT fui;^ JE^ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Lyrasis IViembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/haroldejohnsonjeOOgise The Harold E. Johnson Jean Sibelius Collection at Butler University A Complete Catalogue Gisela Schliiter Terrell 1993 Rare Books & Special Collections Irwin Library Butler University Indianapolis, Indiana oo Printed on acid-free paper Produced by Butler University Publications ©1993 Butler University 500 copies printed $15.00 cover charge Rare Books & Special Collections Irwin Library, Butler University 4600 Sunset Avenue Indianapolis, Indiana 46208 317/283-9265 Dedicated to Harold E. Johnson (1915-1985) and Friends of Music Everywhere Harold Edgar Johnson on syntynyt Kew Gardensissa, New Yorkissa vuonna 1915. Hart on opiskellut Comell-yliopistossa (B.A. 1938, M.A. 1939) javaitellyt tohtoriksi Pariisin ylopistossa vuonna 1952. Han on toiminut musiikkikirjaston- hoitajana seka New Yorkin kaupungin kirhastossa etta Kongressin kirjastossa, Oberlin Collegessa seka viimeksi Butler-yliopistossa, jossa han toimii musiikkiopin apulaisprofessorina. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1963-1964

TANGLEWOOD VAyf PT-TOM JL JL VX X II v/1 i Erich Leinsdorf Music Director i^pi FOURTH WEEK July 24, 25, 26, 1964 DLKLonlKL r LM 1 VAL Erich Leinsdorf and the Boston Symphony: • Mahler's Symphony No. 5 • u Excerpts from Wozzeck" MAHLER/ SYMPHONY No. 5 BERG/WOZZECK(Excerptt)/Phyllis Curtin, Soprano BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ERICH LEINSDORF Erich Leinsdorf and the Boston Symphony interpret the complexi- ties of Mahler's score with a rare depth of understanding. In this impressive new Dynagroove album, the emotions, tensions and tonal spectrum of the work come through with brilliant clarity. Soprano Phyllis Curtin is featured as Marie in highlights from Berg's stark, tragic opera, "Wozzeck" Handsomely packaged 2-record set in- cluding text piece by Neville Cardus. T% f^ k \f\r*4-f\r 1^. Available July 17th at the Tanglexvood Music Store 1Wjl\ V IdOl AS| ©The most trusted name in sound ^*L Boston Symphony Orchestra ERICH LEINSDORF, Music Director RICHARD BURGIN, Associate Conductor Berkshire Festival, Season 1964 TWENTY-SEVENTH SEASON MUSIC SHED AT TANGLEWOOD, LENOX, MASSACHUSETTS FOURTH WEEK Concert Bulletin, ivith historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk Copyright, 1964 by Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. The Trustees of The BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. President Vice-President Treasurer Henry B. Cabot Talcott M. Banks Richard C. Paine Abram "Berkowitz C D. Jackson Sidney R. Rabb Theodore P. Ferris E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Charles H. Stockton Francis W. Hatch Henry A. Laughlin John L. Thorndike Haroed D. Hodgkinson John T. Noonan Raymond S. Wilkins Mrs. James H.