Schenker's First “Americanization”: George Wedge, the Institute of Musical Art, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

For Children 1

1 500BOOKS FOR CHILDREN 1 NORA E. BEUST Specialist in School Libraries /114.4 14. or, . 11 4 -es . - ,0 I . A PW oh Bulletin 1939, No. 11 It t<1 maim STATICS DEPARTMENT OPTILEINTERIOR,HaroldL. Ickes,Seeman MIMIOFIDUCATION, J. W. Studebaker,Ceuradosiesar ailed States GarmasheetPrintingMks Wesklegtsa 44t re Oa tif fla 011111010111,stOfDmINIIN, WasiOntra,D. A hieslasea* . ,': i ....- ,..- i: : ... 4.1 :. - '' , .t t^ bayV . - - .4,)' 4: I r * $'` :f . o W...1*- 4"4'-' ' .''... r . 4l 4.47. .5 14.11$f 4'.'t :..!`'.: t I ' . r :" ' gi ' ,k, i 4't, 'I: - 4 , ' '... ..!1' 'et i; s :- i . 7.% t . t .. nzs 1 - 7,...., k trd, '; "'" ". , e" e 7 4 , J t, RAY, Ars "274LV,INi .th Wei LW" lb 1 s . CONTENTS Page FOREWORD_ 01, 411. v bi PRIPIACZ _ SECTIONI (Grades 1-3)__ 6 SECTIONII (Grades 4-6) ,. .......... - - - ........___ 20 , SECTIONIII (Grades 7-8) 38 NEWBRRTMEI3AL BOOKS _ 53 CALDICOTI' AWARDS__IMP MO OW as I ND 55 ILLUSTRATORS 59 PuBusaxas. 66 k hoax_ 110 am, airo 69 vt, In I 1 *0' e. 7t. ' A. " -.Or' ' ,s a __,* '--. .4- a .I, ,,,e vala. a,ra ., . * * i f, Or . N, :' * 10 ara.." .1,-*-vot. 1 v.irjrr; ,- ''4" 1,4-*vf.1.4 5 at: IC .._." 1. 1 ''''', , -4` -. % ... t p - _., J:, tit .3,..7" t. '-,,,....,....;lf,- riit, t,..12 ..PFle-... re .0* - .).... 1- . - ' .i. 41; , '9.14 a Onegift thefairiesgave me.(Three Theycommonlybestowedof yore.) Thelove ofbooks,the goldenkey Thatopenstheenchanteddoor. IOW ANDREW LANG. FromBallade oftheBookworm. Iv- - - 4. -'k,' 7 t45.11.. et* 0. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms international A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North! Z eeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9130640 The influence of Leonard B. Smith on the heritage of the band in the United States Polce, Vincent John, Ph.D. -

Booklet of Festival

The St. Petersburg N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov State Conservatory (Russia) 23–30 ‘10 ‘2009 The Kazan Nazib Zhiganov State Conservatory (Russia) The Yerevan Komitas State Conservatory (Armenia) The Juilliard School of Music (New York, USA) F e s t i v a l Western Michigan University (Kalamazoo, USA) IX The Peabody Conservatory of The Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, USA) University of Southern California (Los Angeles, USA) The Tianjin Conservatory of Music (People’s Republic of China) Royal College of Music (London, Great Britain) International Music Academy (Milan, Italy) The Queen Sofia College of Music (Madrid, Spain) The Royal Danish Academy of Music (Copenhagen, Denmark) Carl Nielsen Academy of Music (Odense, Denmark) Rotterdam Conservatory (The Netherlands) The Luxembourg Conservatory of Music (Grand Duchy of Luxembourg) Academy of Music and Theatre (Hamburg, Germany) The State University of Music and Performing Arts (Stuttgart, Germany) The University of Music (Wu_rzburg, Germany) Franz Liszt Academy of Music (Budapest, Hungary) Stanislaw Moniuszko Academy of Music (Gdansk, Poland) The Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance (Israel) International Conservatory Week S t.Petersburg Официальные инструменты IХ фестиваля «Международная неделя консерватории»: концертный орган фирмы EULE концертные рояли фирмы Steinway & Sons Попечительский совет фестиваля Генеральное Генеральное Генеральное консульство Генеральное консульство Генеральное консульство Генеральное консульство США консульство Королевства Федеративной Венгерской Республики Республики -

Symphony Shopping

Table of Contents | Week 1 7 bso news 15 on display in symphony hall 16 bso music director andris nelsons 18 the boston symphony orchestra 21 a message from andris nelsons 22 this week’s program Notes on the Program 24 The Program in Brief… 25 Dmitri Shostakovich 33 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky 41 Sergei Rachmaninoff 49 To Read and Hear More… Guest Artist 55 Evgeny Kissin 58 sponsors and donors 78 future programs 82 symphony hall exit plan 83 symphony hall information the friday preview talk on october 2 is given by bso director of program publications marc mandel. program copyright ©2015 Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. program book design by Hecht Design, Arlington, MA cover photo of Andris Nelsons by Chris Lee cover design by BSO Marketing BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Symphony Hall, 301 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, MA 02115-4511 (617)266-1492 bso.org andris nelsons, ray and maria stata music director bernard haitink, lacroix family fund conductor emeritus seiji ozawa, music director laureate 135th season, 2015–2016 trustees of the boston symphony orchestra, inc. William F. Achtmeyer, Chair • Paul Buttenwieser, President • George D. Behrakis, Vice-Chair • Cynthia Curme, Vice-Chair • Carmine A. Martignetti, Vice-Chair • Theresa M. Stone, Treasurer David Altshuler • Ronald G. Casty • Susan Bredhoff Cohen • Richard F. Connolly, Jr. • Alan J. Dworsky • Philip J. Edmundson, ex-officio • William R. Elfers • Thomas E. Faust, Jr. • Michael Gordon • Brent L. Henry • Susan Hockfield • Barbara W. Hostetter • Stephen B. Kay • Edmund Kelly • Martin Levine, ex-officio • Joyce Linde • John M. Loder • Nancy K. Lubin • Joshua A. Lutzker • Robert J. Mayer, M.D. -

Doctoral Dissertation Template

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE ALLISON NELSON: PIANIST, TEACHER AND EDITOR A DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By LYNN WORCESTER Norman, Oklahoma 2015 ALLISON NELSON: PIANIST, TEACHER AND EDITOR A DOCUMENT APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC BY ______________________________ Dr. Jane Magrath, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Stephen Beus, Co-Chair ______________________________ Dr. Barbara Fast ______________________________ Dr. Edward Gates ______________________________ Dr. Eugene Enrico ______________________________ Dr. Joseph Havlicek © Copyright by LYNN WORCESTER 2015 All Rights Reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work would not have been possible without the guidance and support of the faculty members who served on my committee, Dr. Jane Magrath, Dr. Barbara Fast, Dr. Edward Gates, Dr. Eugene Enrico, Dr. Stephen Beus and Dr. Joseph Havlicek. To Dr. Jane Magrath: Thank you for your patience and continued support through every turn and for showing me how to be the finest professional I can be. Your guidance has allowed me to come in to my own as a pianist, teacher and writer. Special gratitude is reserved for Dr. Allison Nelson who shared her time, memories, and efforts over the course of this past year. Her wisdom, energy, and passion for music will stay with me for the rest of my life. Thank you to all of Dr. Nelson’s colleagues and former students who shared their time and participated in this study. A special thanks is owed to my family—my father, Mark Worcester, my mother, Eiki Worcester and my sister, Leya Worcester—whose love and dedication will always be cherished. -

Hifi /Stereo Review of April 1968

fulStereo Review APRIL 1968 60 CENTS NINE SOLUTIONS TO THE STEREO -INSTALLATION PROBLEM WHICH RECORDINGS FOR A DESERT -ISLAND DISCOGRAPHY? *AMERICAN COMPOSERS SERIES: WALLINGFORD RIEGGER * Hifi/StereoReview APRIL 1968 VOLUME 20 NUMBER 4 THE MUSIC GIACOMO MEYERBEER'S OPERA OF THE SEVEN STARS A report on Les Huguenots and Wagner inLondon HENRY PLEASANTS 48 THE BASIC REPERTOIRE Beethoven's Symphony No. 1, in C Major MARTIN BOOKSPA 53 WALLINGFORD RI EGGER A true original among the Great American Composers RICHARD FRANKO GOLDMAN 57 DESERT -ISLAND DISCOGRAPHY One man's real -life answers to a popular speculation 68 THE BAROQUE MADE PLAIN A new Vanguard release demonstrates Baroque ornamentation IGOR KIPNIS 106 THE EQUIPMENT NEW PRODUCTS A roundup of the latest high-fidelity equipment 22 HI-FI Q & A Answers to your technical questions LARRY KLEIN 28 AUDIO BASICS Specifications XX: Separation HANSH. FANTEL 34 TECHNICAL TALK ProductEvaluation;Hirsch -HoucklaboratoryreportsontheA ltec711stereo FM receiver, the Switchcraft 307TR studio mixer, and the Wollensah 5800 tape re- corder JULIAN D. HIRSCH 37 STEREO INGENUITY Clever and inexpensive component cabinets-a photo portfolio LARRY KLEIN 70 TAPE HORIZONS Tape and Home Movies DRUMMOND MCINNIS 127 THE REVIEWS BEST RECORDINGS OF THE MONTH 75 CLASSICAL 81 ENTERTAINMENT 109 STEREO TAPE 123 THE REGULARS EDITORIALLY SPEAKING WII.LIAM ANDERSON 4 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 6 GOING ON RECORD JAMESGOODFRIEND 44 ADVERTISERS' INDEX; PRODUCT INDEX 130 COVER: .1. B. S. CHARDIN: STILL LIFE WITH HURDY-GURDY: PHOTO BY PETER ADEI.IIERG. EURDPF.AN ART COLOR SLIDE COMPANY, NEW YORK Copyright 1968 by Ziff -Davis Publishing Company. All rights reserved. -

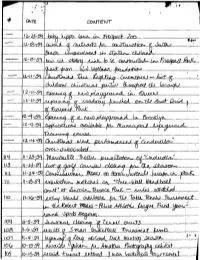

-Fo Oc Cs>Fiifr[Tftk<L- — Lof <R

, -fo Oc Cs>fiifr[tfTk<l- — Lof <r - : OXAK" — *5h(VF 6&i-f[/N3 uUPcflUY- J[« (JobL 3 %OAArLdc Mk/J /\ifaxir\Q fU> fbbxJ JUtkLsMc •» • 3 • \HxKxapai tfom pxrz. 5(o '<3>^ 55 5\ 5o (o-3-&\ fa tlJt Brot&* {) 5-22- 45 . c^ J .^^"io^U; 1&uuu^ajp<& CM-M^cyL5ta^ l i /cto^TLT. 6LO^ h&cQtyOte 51 . a -t 15* 35 <?4 u S3 •52. U -CjLl€hj01&-- Iv3l ^tcL?U J^UMj^tO^ zi ^ _.Ei-ciw_p4#_ QoU_. GIMJX ^c^co6 &cJ._^st. Z3 C^dLG— Cr?. fihfoJ^dtf'Gsi 2.2, ^ (jo Z( 2O Q 16 w 17 i ^ 15 4-2-5? <fl 13 II -uSj-f <n. fads - Ste&ttelL TcujrNztrtLti-. .. IP.. of q ..s. - past _ i A 1-13- Q od. .c?_ ttCJL 3 a 2 (-15-59 u % 7 i* DEPARTMEN O F PA R K S ARSENAL, CENTRAL PARK REGENT 4-1000 FOR RELEASE THURSDAY, DECEMBER 24, 1959 l-l-l-60M-707199(58) 114 The Department of Parks announces that a •baby- female hippopotamus weighing approximately 70 lbs. was born on November 24, 1959, at the Prospect Park &oo in Brooklyn. The mother, Betsy, now 9 years old, arrived at the Prospect Park &oo on September 8, 1953, and the sire, "Dodger", was 3 years old v/hen he arrived in 1951. However, "Dodger" passed away on October 8, 1959, and will not be around to hand out cigars. The new offspring has been named "'Annie". N.B. s Press photographs may be taken at tine* 12/23/59 DEPARTMEN O F PA R K S ARSENAL, CENTRAL PARK REGENT 4-1000 FOR RELEASE SUHDAY, D5CBMHBR 20, 1959 M-l-60M-529Q72(59) 114 The Borough President of Richmond and the Department of Parks announce the award of contracts, in the amount of $2,479,487, for the second stage of construction of the South Beach improvement in Staten Islitnd. -

Volume 66, Number 07 (July 1948) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 7-1-1948 Volume 66, Number 07 (July 1948) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 66, Number 07 (July 1948)." , (1948). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/171 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. utTL II Lh > r tMii.L gmm THEODORE PRESSER Educator - Publisher - Philanthropist 1848-1925 ONE HUNDREDTH ANNIVERSARY Founder of The Music Teachers National Association, The Etude Music Magazine — Theodore Presser Company The Presser Foundation . Hans Schweiger, who since 1944 has the Fort Bayne of the seventy-fifth been conductor of The Music Season has In- (Indiana) Philharmonic Orchestra, i annual assembly of the Chatauqua conductorship of the Kansas stitution will open at Lake Chautauqua accepted the a position vacated by on July 16 with an operatic performance City Philharmonic, he became conductor conducted by Alfredo A alenti. On July Efrem Kurtz when (Texas) Symphony 17 the Chautauqua Symphony Orchestra, of the Houston under the baton of Franco Autori, will Orchestra. open a series of twenty-four concerts. Prof. Paul Stoye, concert pianist and twenty-seven years head of The Goldman Band, on June 18. -

Music for the Microphone: Network Broadcasts and the Creation of American Compositions in the Golden Age of Radio Akihiro Taniguchi

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2003 Music for the Microphone: Network Broadcasts and the Creation of American Compositions in the Golden Age of Radio Akihiro Taniguchi Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC Music for the Microphone: Network Broadcasts and the Creation of American Compositions in the Golden Age of Radio By AKIHIRO TANIGUCHI A Dissertation submitted to the School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2003 Copyright ©2003 Akihiro Taniguchi All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Akihiro Taniguchi defended on 15 May 2003. ______________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Dissertation ______________________________ Jane Piper Clendinning Outside Committee Member ______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Committee Member ______________________________ Michael B. Bakan Committee Member Approved: ________________________________________________________ Jon Piersol, Dean, School of Music The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ........................................................................................................................ v List of Music Examples........................................................................................................ -

William Schuman's Literature and Materials Approach: a Historical Precedent for Comprehensive Musicianship

WILLIAM SCHUMAN'S LITERATURE AND MATERIALS APPROACH: A HISTORICAL PRECEDENT FOR COMPREHENSIVE MUSICIANSHIP By JONATHAN STEELE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1988 ^p p LIBRARIES Copyright 1988 by Jonathan Edward Steele ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude for the guidance and encouragement given by my major professor, Dr. John White, throughout my program of study at the University of Florida and particularly during the writing of this dissertation. I am also grateful for the helpful and precise assistance provided by my committee members in their review of my work. Their many hours of work are greatly appreciated. I owe a debt of gratitude to Clearwater Christian College for the substantial assistance and encouragement given to me in my doctoral studies. Most of all, I am thankful for my wife, Bea. Without her unending love, patience, and support, I would not have finished this task. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS page ABSTRACT vi CHAPTER ONE - INTRODUCTION 1 Statement of the Problem 1 Objectives 5 Background 6 The Juilliard School 6 The Literature and Materials Approach .... 8 History of the Comprehensive Musicianship Approach 11 The Young Composers Project . 11 The Contemporary Music Project and Comprehensive Musicianship 17 Background on William Schuman 22 Biography 22 Philosophy 38 Musical Output 41 CHAPTER TWO - REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE 45 Scholarly Research 46 Bibliographies 47 Periodical Literature 48 Biographies 52 CHAPTER THREE - METHODOLOGY 54 Preliminary Study 54 Interview With William Schuman 54 Interview With Michael White 56 Interview Protocol 58 Other Interviews 59 Follow-up Study 60 iv CHAPTER FOUR - COMPARISON OF APPROACHES 61 The Literature and Materials Approach (L and M) . -

Instead Draws Upon a Much More Generic Sort of Free-Jazz Tenor Saxophone Musical Vocabulary

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. GEORGE AVAKIAN NEA JAZZ MASTER (2010) Interviewee: George Avakian (March 15, 1919 – November 22, 2017) Interviewer: Ann Sneed with recording engineer Julie Burstein Date: September 28, 1993 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Description: Transcript, 112 pp. Sneed: I’m Ann Sneed. We are in Riverdale. We’re interviewing George Avakian. There’s so many things to say about you, I’m just going to say George Avakian and ask you first, why jazz? Avakian: I think it happened because I was born abroad, and among the things that came into my consciousness as I was growing up was American popular music, and then it drifted in the direction of jazz through popular dance bands, such as the Casa Loma Orchestra, which I heard about through the guys who were hanging around the home of our neighbor at Greenwood Lake, which is where we went in the summers. We had a house on the lake. Our next-door neighbors had two daughters, one of whom was my age and very pretty, Dorothy Caulfield, who incidentally is responsible for Holden Caulfield’s last name, because J. D. Salinger got to know her and was very fond of her, named Holden after her family name. These boys came from the Teaneck area of New Jersey. So it was a short drive to Greenwood Lake on a straight line between New York and New Jersey. They had a dance band, the usual nine pieces: three brass, three saxophones, three rhythm.