James Loves Severus, but Only in Japan. Harry Potter in Japanese and English-Language Fanwork

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“50 Reasons Why Tokyo Is ...N the World | Cnngo.Com”のプレビュー

12/11/12 50 reasons why Tokyo is the greatest city in the world | CNNGo.com Register Sign In CNN International LATEST GUIDES TOKYO ESSENTIALS iREPORT CONTESTS TV Follow Like 291k 50 reasons Tokyo is the world's greatest city This town is so magnificent that "being from the future" didn't even make the list 5 March, 2012 Like Send 4,323 people like this. Be the first of your friends. 49 Tweet 579 Tokyo -- a city hard to describe. But we've given it a shot. By Steve Trautlein, Matt Alt, Hiroko Yoda, Melinda Joe, Andrew Szymanski and W. David Marx. 1. The world's most sophisticated railways With 13 subway lines and more than 100 surface routes run by Japan Railways and other private companies, Tokyo's railway system seems like it was designed to win world records. It's rare to find a location in the metropolitan area that can’t be reached with a train ride and a short walk. Now, if only the government could devise a way to keep middle-aged salarymen from groping women onboard. 2. Sky-high one-upmanship Tokyo Sky Tree. (Tim Hornyak/CNNGo) When officials in Tokyo learned that the new Guangzhou TV & Sightseeing Tower in China would be 610 meters tall -- the same height that was planned for Tokyo Sky Tree, then under construction -- they did what any rational person would do: They added 24 meters to the top of Sky Tree to preserve its claim as the world’s tallest tower. Now complete and scheduled to open in May, the Guinness-certified structure features shops, restaurants and an observation deck that lets you see almost all the way to Guangzhou. -

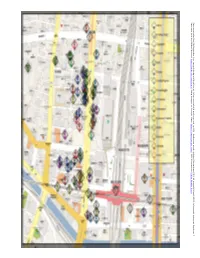

Map a Ssem B Le D an D Ma Rk Ed by Zim. Softw a Re Used

Data compiled by ZiM (parabellum.rounds(at)gmail(dot)com). Map assembled and marked by ZiM. Software used: Adobe Photoshop CS3, Microsoft Word 2007, Microsoft Internet Explorer 7. Data and text by Akiba Channel: http://akiba‐ch.com/map/. Map images by Google Maps: http://maps.google.com/. PDF Conversion White Rabbit Press Retro Visual/Audio 1 Super Potato 3F Nintendo, Sega; 4F Sony; 5F Retro game arcade. 1 Sofmap Music CD Store 1F: New CDs, JPOP CDs; 2F: Anime, Game CDs; 3F: Best retro game store in Akiba, on upper floors. New, used CDs; 4F: Event 2 Retro Game Store #7 New store, next to Sofmap Store. Retro games. PC Games Trading Cards 1 Medio! X PC games. Rarities displayed. 1 Yellow Submarine Well stocked with anime and trading cards. 2 Sofmap PC Game/Anime B1: Used PC games, game OST CD; 1F: New PC Trading Card Store Store Games, Music CDs, game magazines; 2F: New Radio Kaikan 7F Anime DVD, Used Anime OST; 3F: Figures 2 Hobby Station Alternate figures and trading card store. 3 Getchu‐ya 3F store. Few games in stock. Rental showcase on 3 Amenity Dream Recommended trading card shop in Akiba, on 6F. 2F, used game/anime/CD store on 1F. Biggest stock of single cards, playing space. Recreation 4 Yellow Submarine Magic‐ Vast trading card booster packs stock. Expensive. 1 Karaoke Pasera Themed after popular anime and shows. ers 2 GeraGera Manga Cafe Few places to access net. Pricey. Transport 3 AION Pachinko place. Anime, game themed machines. 1 Akihabara JR Station 4 Island Pachinko place on bottom floor. -

Manga Vision: Cultural and Communicative Perspectives / Editors: Sarah Pasfield-Neofitou, Cathy Sell; Queenie Chan, Manga Artist

VISION CULTURAL AND COMMUNICATIVE PERSPECTIVES WITH MANGA ARTIST QUEENIE CHAN EDITED BY SARAH PASFIELD-NEOFITOU AND CATHY SELL MANGA VISION MANGA VISION Cultural and Communicative Perspectives EDITED BY SARAH PASFIELD-NEOFITOU AND CATHY SELL WITH MANGA ARTIST QUEENIE CHAN © Copyright 2016 Copyright of this collection in its entirety is held by Sarah Pasfield-Neofitou and Cathy Sell. Copyright of manga artwork is held by Queenie Chan, unless another artist is explicitly stated as its creator in which case it is held by that artist. Copyright of the individual chapters is held by the respective author(s). All rights reserved. Apart from any uses permitted by Australia’s Copyright Act 1968, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright owners. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher. Monash University Publishing Matheson Library and Information Services Building 40 Exhibition Walk Monash University Clayton, Victoria 3800, Australia www.publishing.monash.edu Monash University Publishing brings to the world publications which advance the best traditions of humane and enlightened thought. Monash University Publishing titles pass through a rigorous process of independent peer review. www.publishing.monash.edu/books/mv-9781925377064.html Series: Cultural Studies Design: Les Thomas Cover image: Queenie Chan National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Title: Manga vision: cultural and communicative perspectives / editors: Sarah Pasfield-Neofitou, Cathy Sell; Queenie Chan, manga artist. ISBN: 9781925377064 (paperback) 9781925377071 (epdf) 9781925377361 (epub) Subjects: Comic books, strips, etc.--Social aspects--Japan. Comic books, strips, etc.--Social aspects. Comic books, strips, etc., in art. Comic books, strips, etc., in education. -

WISH Times English Ver

October 2020 ver.39 WISH Times English Ver. Restart... Dorm Life! -CoNteNts- ・A LearNiNg ExperieNce Outside of the Classroom -SI Programs aNd SI Awards- ・“If You Gaze For LoNg INto AN Abyss, The Abyss Gazes Also INto You.” - NakaNo Broadway- ・Home cookiNg iN the Dorm! Easy Recipes for Local Gourmet ・Special Feature oN the WISH 9th Floor A LearNiNg ExperieNce Outside of the Classroom -SI Program aNd SI Awards- Writer:Ryoei Trasnlator:Yui Designer:Mei I would like to talk about the SI programs aNd SI Awards oN this INtroductioN WISHTimes issue because it’s beeN a year siNce I weNt oN the SI Award trip. While I was quaraNtiNiNg iN my hometowN, I oNce agaiN realized how awesome it was to live iN WISH. I especially waNt to stress about how amaziNg the SI programs aNd SI Awards are, the reasoN why I am writiNg this article. The SI programs is a uNique learNiNg program that iNcludes group work aNd lectures, held from 19:00 to 20:30 duriNg weekdays, aNd the SI Award is aN overseas traiNiNg program for studeNts that perform well iN the SI programs. IN the SI programs you caN acquire skills aNd kNowledge that are Necessary for wheN you start workiNg, such as effective commuNicatioN. The program’s ageNda varies from career semiNars, where you get advice from people workiNg iN various iNdustries, aNd study abroad symposiums held by the RAs. It may be hard for studeNts who have extra activities or classes late at Night to atteNd the SI programs. However, my frieNd that is majoriNg iN eNgiNeeriNg –the departmeNt that is said to be the busiest– was elected for the SI Award, aNd I maNaged to atteNd SI programs despite haviNg extra activities duriNg the weekdays. -

The Cultural Dynamic of Doujinshi and Cosplay: Local Anime Fandom in Japan, USA and Europe

. Volume 10, Issue 1 May 2013 The cultural dynamic of doujinshi and cosplay: Local anime fandom in Japan, USA and Europe Nicolle Lamerichs Maastricht University, Netherlands Abstract: Japanese popular culture unifies fans from different countries and backgrounds. Its rich participatory culture is beyond any other and flourishes around comics (manga), animation (anime), games and music. Japanese storytelling showcases elaborate story worlds whose characters are branded on many products. The sub genres of Japanese pop-culture and the lingua franca of their audiences shape Western fandom. In this article, I scrutinize the global dynamic of manga. I specifically focus on the creation of fan manga (‘doujinshi’) and dress- up (‘cosplay’) as two migratory fan practices. The form and content of fan works, and the organizational structure behind them, varies intensely per country. If manga is an international language and style, where is its international fan identity located? In this article, I explore this uncharted territory through ethnographic views of diverse Western and Japanese fan sites where these creative practices emerge. This ethnographic overview is thus concerned with the heterogeneous make-up and social protocols of anime fandom. Keywords: Anime fandom, doujinshi, cosplay, conventions, ethnography Introduction Japan’s global and exotic identity is historically rooted. In the nineteenth century, Euro- Americans performed their fascination for the island through ‘Orientalism’ in Western impressionist art, Zen gardens and architecture (Napier, 2007; Said, 1978). When World War II penetrated this culturally rich image, the fascination for Japan became more ambivalent, characterized by both fear and curiosity. By now, the country’s global identity, which lingers between East and West, inspires Western corporate businesses, art and media as it represents a mixture of spiritual traditions, strong labour and family morals, as well as an advanced technocapitalist model (Ivy, 1995; Wolferen, 1995). -

Japan Specialist Since 1912 Mt

JapanIndividual travel, group tours & excursions Japan specialist since 1912 Mt. Fu ji Os a k a To kyo Kyoto Kanazawa Takayama Mt. Fuji Hiroshima Kyoto Nagoya Osaka Fukuoka Matsuyama Nagasaki Kumamoto SHIKOKU KYUSHU OKINAWA Okinawa CONTENTS ABOUT US ······························································ 04 JAPAN ····································································· 06 JAPAN RAIL PASS ·················································· 08 EXCURSIONS ························································· 10 SELF-GUIDED TOURS EXPLORE JAPAN BY RAIL ····································· 14 Sapporo JAPAN HIGHLIGHTS 12 DAYS ······························· 15 JAPAN HIGHLIGHTS 16 DAYS ······························· 15 THE SEASONS ······················································· 16 SPRING IN JAPAN ·················································· 17 AUTUMN IN JAPAN ··············································· 17 HOKKAIDO FAST AND ACTIVE ················································· 18 Aomori MODERN AND TRADITIONAL ······························ 19 CYCLE ON SHIKOKU ·············································· 19 POP CULTURE ························································ 20 POP JAPAN! ··························································· 21 KANSAI BANZAI! ··················································· 21 Sendai OFF THE BEATEN TRACK ······································ 22 NORTH JAPAN (TOHOKU) ····································· 23 RUSTIC JAPAN ······················································· -

Deus Ex Machina

001 002 Cuaderno de máquinas y juegos | Nº 1 | Año 2017 003 DEUS EX MACHINA Cuaderno de máquinas y juegos N.º 1 | Año 2017 | Madrid [España] Publicado por Plataforma Editorial Sello ArsGames [sello.arsgames.net] [[email protected]] Edita: Asociación ArsGames [coord.: José Andrés Fernández] Diseño y producción gráfica: Sello ArsGames [Mr. Moutas] Ilustración de cubiertas: Díaz-Faes Compilación de textos: Deus Ex Machina [Guillermo G. M.] [deusexmachina.es] [[email protected] ] ISSN: 2529-9662 Depósito legal: M-23110-2016 Se permite la reproducción total o parcial de la obra y su di- fusión telemática para uso personal de los lectores siem- pre y cuando no sea con fines comerciales. Creative Commons-Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 3.0 España (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ES) AGRADECIMIENTOS — María Pérez Recio — Ricardo Suárez — Carmen Suárez — — Alicia Guardeño — Guillermo G. M. — Rodrigo Aliende — — Pablo Algaba — Galamot Shaku — Paula Rivera Donoso — — Israel Fernández — Isidoro Vélez — Alonso & Moutas — — David Rodríguez — Vctr_Seleucos — Toni Gomariz — — Ignasi Meda Calvet — Jenn Scarlett — Isa Pirracas — — Jorge González Sánchez — Marçal Mora — Díaz-Faes — — Eva Cid — Isi Cano — Rutxi García — Start-t Magazine Books — ARCHIVO EN CLAVE DE SOMRA LA FÓRMULA DE GEOFF CRAMMOND Eva Cid ................................................ 012 Isidoro Vélez ............................................060 ‘READY PLAYER ONE’: UN POCO DE INTELIGENCIA ARTIFICIAL UNA NOVELA SOBRE VIDEOJUEGOS David Rodríguez ........................................064 -

Day 1, Tuesday July 05, 2016

Tokyo for Jeff and Lauren Day 1, Tuesday July 05, 2016 1: Rest Up at the Aman Tokyo (Lodging) Address: Japan, 〒100-0004 Tokyo, Chiyoda, 大手町1-5-6 About: The hotel: Set in top 6 floors of a sleek, modern high-rise, this luxury hotel is an 8-minute walk from the bustling Tokyo Station, and 3 km from the landmark Tsukiji Market With floor-to-ceiling windows and sweeping city views, the elegant rooms, decorated in stone, wood and paper screens, feature free Wi-Fi, flat-screen TVs, deep soaking tubs and minibars. Suites add living rooms and wine cellars The spa: Drawing on traditional natural remedies and the principles of balancing mind and body, Aman Spa offers an integrated approach to wellbeing. Several Spa treatment rooms are complemented by large Japanese-style hot baths and steam rooms, a 30-metre heated pool with city views, a fitness centre equipped with the latest cardiovascular and weight training machinery, as well as a dedicated yoga and Pilates studio. Their minute seasonal journey starts off with a foot bath comprised of hot water, sake koji paste, and Japanese sea salt followed by a body wrap made of Japanese rice bran, clay, yuzu (a citrus fruit packed with skin-brightening vitamin C), ginger, and pine essential oils. You can choose a 90 minute or 60 minute massage with this option. At 46,000 yen, it's certainly pricey, but you'd be hard-pressed to find a spa treatment this luxurious anywhere but here. Opening hours Sunday: Open 24 hours Monday: Open 24 hours Tuesday: Open 24 hours Wednesday: Open 24 hours Thursday: Open 24 -

Japan Summer Manga Tour 2020

Japan Summer Manga Tour 2020 8 – 16 July 2020 The holiday of a lifetime for fans of manga, anime and all aspects of Japanese pop culture. As well as visits to Akihabara and Nakano Broadway, we take you to the Ghibli Museum where the work of this wonderful Japanese animation studio can be admired! Experience Tokyo in all its neon glory with the original Manga Tour. We don’t just visit Japan – we live it! Japan Summer Manga Tour 2020 The Itinerary 8-9 July: UK-Tokyo Fly overnight from London Heathrow on 8 July to Tokyo. (Non-UK passengers will have to make their own flight arrangements). Upon arrival the next day (9 July), you will be transferred to your hotel in Tokyo by private coach. 10 July: Ghibli Museum, Nakano Broadway After breakfast we will visit the superb Ghibli Museum in Mitaka, designed by one of the world’s top animators, Hayao Miyazaki – Academy Award winner for “Spirited Away”. Then we head to Nakano Broadway – the mega-mall home to 13 July: Akihabara may want to join one of our Optional trips. Mandarake and countless other manga The first is a day out to the magical world After breakfast, we visit Akihabara – and memorabilia speciality stores. of Tokyo Disneyland. Alternatively, how Tokyo’s “Electric Town” and home to about a fully-guided tour to Mt. Fuji and dozens of anime, manga and electronic the beautiful nearby resort of Hakone, 11 July: Shinjuku, Tokyo Tower, goods stores. Asakusa, Sunshine City returning to Tokyo by Bullet Train? Today we start with an orientation of 14 July: Shibuya If you decide to simply stay -

![TSE NOTICE Mar.19, 2020 (Thu.) [Attachment] Changes in Number of Listed Shares, Etc](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4055/tse-notice-mar-19-2020-thu-attachment-changes-in-number-of-listed-shares-etc-4194055.webp)

TSE NOTICE Mar.19, 2020 (Thu.) [Attachment] Changes in Number of Listed Shares, Etc

Feb. 2020 (Reference Translation) TSE NOTICE Mar.19, 2020 (Thu.) [Attachment] Changes in Number of Listed Shares, etc. in Connection with Exercise of Subscription Warrants, etc. (Relevant Period Feb. 01, 2020 - Feb. 29, 2020) (Note) 1. No. of Listed Shares at End of Month No. of listed shares for Common Stock, Preferred Stock, etc. (*Code 2593-5 is Type-1 Preferred Stock of ITO EN, LTD.) When exercising Subscription Warrants in cases where treasury stocks will be transferred, the number of listed shares may not increase even after decreasing the residual amount of bonds, etc. After acquiring CBs subject to call in cases where retirement has not been conducted, the number of listed shares may increase without a decrease in the residual amount of bonds. 2. Primary Reasons for Changes Exercise of Bonds with Subscription Warrants …Due to Exercise of Bonds with Subscription Warrants Conversion of Preferred Stock, etc. …Due to Conversion of Stock (Preferred Stock, etc.) which can be converted into another type of Stock Exercise of CBs …Due to Exercise of CBs, and new share issuance by acquisition of Share Options subject to Call Exercise of Subscription Warrants …Due to Exercise of Subscription Warrant, and new share issuance by acquisition of Share Options subject to Call Public Offering …Due to Public Offering and Overseas Offering Third-Party Allotment, etc. …Due to Third-Party Allotment, Green Shoe Option (pursuant to the Cabinet Office Ordinance on the Disclosure of Corporate Affairs, etc. Article 19, Paragraph 2, Item 1, sub-item L.1), Allotment of New Shares as stock-based remuneration and Private Placement to Specified Investors for listed companies on TOKYO PRO Market Retirement of Treasury Stocks …Due to Retirement of Treasury Stocks 3. -

“Otaku”? by Tony Mcnicol Author Tony Mcnicol

VIEWPOINT Photos: Tony McNicol Who Are You Calling “Otaku”? By Tony McNicol Author Tony McNicol didn’t take much research before I real- ized that is often far from the truth. The first article I wrote was about an otaku test designed to select 100 elite otaku from all over Japan. When I interviewed one of the top scorers over a beer, I was bemused to find him an impeccably pre- sented young salaryman from an emi- nently respectable Japanese corporation. In fact, one of the weirdest otaku-type hobbies I’ve ever covered involved not 20-something men, but middle-aged Toy figures on sale at Mandarake hobby store Resin dolls made by Kyoto-based Volks Inc. are women. I met them when I wrote a in Nakano, Tokyo popular with young women, and a few men too. story on a kind of cuddly interactive doll originally targeted at lonely 20-some- Elite Otaku where. Suddenly, being an otaku is cool. thing office ladies. To the maker’s sur- The stereotypical otaku was a geek bar- prise it had become a hit with middle- My wife tells me I’m an otaku, and I’m ricaded into his (definitely his, not her) aged and older women. I went to several beginning to wonder if she might be bedroom, maybe playing on a game con- packed events for “owners” at the manu- right. If you are not familiar with the sole, probably surrounded by shelves of facturer’s HQ: birthday parties, excur- word, online encyclopedia Wikipedia manga, and almost certainly logged onto sions, even a kindergarten entrance day. -

50 Reasons Why Tokyo Is the Greatest City in the World | Cnngo.Com

5 October, 2009 share add to favorites print email World's Greatest City: 50 reasons why Tokyo is No. 1 This town is so magnificent that 'being from the future' didn't even make the list. 90% Users liked this Tell others what you think! you may also like World's Greatest City: 50 reasons why Shanghai is No. 1 FULL ARTICLE World's Greatest City: 50 reasons why Singapore is No. 1 FULL ARTICLE Editor's Note: Matt Alt, Hiroko Yoda, Melinda Joe, Andrew Szymanski, and W. David Marx, CNNGo Tokyo World's Greatest City: 50 City Editor all contributed to this report. reasons why Hong Kong is No. 1 FULL ARTICLE 1. The world's most sophisticated railways With 13 subway lines and over 100 surface routes run by Japan Railways and other private companies, Tokyo's World's Greatest City: 50 railway system seems like it was designed to win world records. It's rare to find a location in the metropolitan area reasons why Bangkok is No. 1 that can’t be reached with a train ride and a short walk. Now, if only the government could devise a way to keep FULL ARTICLE middle-aged salarymen from groping women onboard. 2. The most beautiful place you'll never visit The Imperial Residence sits on three and a half square kilometers of most most greenery that were once valued at more than all of the real estate in read commented California. Although several of the outer Imperial gardens are open to World's Greatest City: 50 reasons why Tokyo is No.