374 Unemployment in Kerala at the Turn of the Century Insights from Cds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KERALA STATE ELECTRICITY BOAIID LIMIT[T)

I KERALA STATE ELECTRICITY BOAIID LIMIT[t) . (Incorporoted under the Contponies Act, 1956) Reg.Office : Vyciyuthi l3havanam, Pattom' Thiruvanantlta;luranr - 695 004 i CI N : U40 1 0 0 K t .20 r1^s}c027 424 Wcbs itc: rvlv',v.ksclt. n. Phone: +91,4772574576,24468tt5,9446008ti84 1]-rnilil: trtrl<-st:[r(o)l<stlbnet.coni. citl<seb@]<seb.in AESTRACT Downstream works for the upcoming 22OkV Substation, Thuravoor - Sanction accorded - Orders issued. Corporate Office (SBU-Tl B.O.(DB)No.3g2l\O2O/D(T,SO&S)/T1lThuravui Down srream works/2020-21/Thiruvananthapuram dated 05.06.2020 Read: 1. Letter No.CE(TS)EE:^/AEEIV/t9-2O/I773 dated 30.10.2019 of the chief Engineer (Trans. south) 2. Lener No.CE(TS)EEt/AEEIV/2O-2t/1O6 dated 28.O4.2O2O of the Chief Engineer (Trans. South) 3. Note No.D(LSO&S)lTl/Thuravur Down Stream Works/19-20 (Agenda ltem No.46l5/2O) 4. Note No.D(I,SO&S)/T1/Thuravur Down Stream Works/19-21lt95 of the chairman & Managing Director. 5. Proceedings of the 53'd meeting of the Board of Directors held on 25.05.2020 (Agenda i 19-05/2020) ORDER KSEBL is constructing a 22OkV Substation at Thuravoor, Cherthala Taluk, under TransGrid project with 2 Nos. of 2OOMVA, zzlltt}kV Transformers and 8Nos. of L10kV outgoing feeders. The Chief Engineer (Transmission South) as per letter read as 1n above submitted a proposal amounting to Rs.77.72Cr for the downstream evacuation works of the 220kV Substation, Thuravoor. The downstream line work includes construction of 37km of 110kV DC feeders by upgrading the existing 66KV SC Vaikom-Cherthala feeders and there after interlinking with the existing 110KV DC feeders to facilitate as outgoing 110kV feeders from the 220kV Substation, Thuravur. -

Dairying in Malabar: a Venture of the Landowning Based on Women's Work?

Ind. Jn. ofAgri. Econ. Vol.57, No.4, Oct-Dec. 2002 Dairying in Malabar: A Venture of the Landowning based on Women's Work? D. Narayana* INTRODUCTION India occupies the second place in the production of milk in the world. The strategy adopted to achieve such remarkable growth in milk production has been a replication of the `Anand pattern' of co-operative dairying in other parts of India using the proceeds of European Economic Commission (EEC) dairy surpluses donated to India under the Operation Flood (OF) programme. The Indian dairy co- operative strategy has, however, proved to be fiercely controversial. One of the major criticisms of the strategy has been that too much focus on transforming the production and marketing technology along western lines has led to a situation where the policy 'took care of the dairy animal but not the human beings who own the animal'. Some dairy unions have come forward to set up foundations and trusts to address the development problems of milk producers. The well-known ones are, The Thribhuvandas Foundation' at Anand, Visaka Medical, Educational and Welfare Trust, and Varana Co-operative Society. They mainly focus on health and educational needs of milk producers and employees. These pioneering efforts have inspired other milk unions. The Malabar Regional Co-operative Milk Producers' Union (MRCMPU)2 has recently registered a welfare trust named, Malabar Rural Development Foundation (MRDF). The mission objective of MRDF is to make a sustainable improvement in the quality of life of dairy farmers by undertaking specific interventions. The planning of interventions for the welfare of dairy farmers in the Malabar region by MRDF called for an understanding of them in the larger social context. -

Pathanamthitta

Census of India 2011 KERALA PART XII-A SERIES-33 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PATHANAMTHITTA VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KERALA 2 CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 KERALA SERIES-33 PART XII-A DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK Village and Town Directory PATHANAMTHITTA Directorate of Census Operations, Kerala 3 MOTIF Sabarimala Sree Dharma Sastha Temple A well known pilgrim centre of Kerala, Sabarimala lies in this district at a distance of 191 km. from Thiruvananthapuram and 210 km. away from Cochin. The holy shrine dedicated to Lord Ayyappa is situated 914 metres above sea level amidst dense forests in the rugged terrains of the Western Ghats. Lord Ayyappa is looked upon as the guardian of mountains and there are several shrines dedicated to him all along the Western Ghats. The festivals here are the Mandala Pooja, Makara Vilakku (December/January) and Vishu Kani (April). The temple is also open for pooja on the first 5 days of every Malayalam month. The vehicles go only up to Pampa and the temple, which is situated 5 km away from Pampa, can be reached only by trekking. During the festival period there are frequent buses to this place from Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kottayam. 4 CONTENTS Pages 1. Foreword 7 2. Preface 9 3. Acknowledgements 11 4. History and scope of the District Census Handbook 13 5. Brief history of the district 15 6. Analytical Note 17 Village and Town Directory 105 Brief Note on Village and Town Directory 7. Section I - Village Directory (a) List of Villages merged in towns and outgrowths at 2011 Census (b) -

1 Poverty and Young Women's Employment

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IDS OpenDocs 1 POVERTY AND YOUNG WOMEN’S EMPLOYMENT: LINKAGES IN KERALA Pradeep Kumar Panda Centre for Development Studies Thiruvananthapuram February 1999 Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the 1998 Out of the Margin 2/International Association for Feminist Economics Conference on Feminist Approaches to Economics, held at the Faculty of Economics and Econometrics, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam and 1998 Second Annual Conference on Economic Theory and Policy, held at the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. The author thanks participants at these presentations and K.P. Kannan, D. Narayana, Ashok Mathur, and Amitabh Kundu for helpful comments and Bina Agarwal, Gita Sen and Arlie Russell Hochschild for insightful discussions. Financial support for this research from Kerala Research Programme on Local Level Development is gratefully acknowledged. The author alone is responsible for any errors. 2 ABSTRACT This paper explores one of the key issues in current research on gender and development: the links between poverty and young women’s employment. Specifically, the following questions were addressed, in the context of Kerala: Which young women work for pay and why? To what extent is a woman’s household economic status -- especially poverty status -- an important determinant of employment, and to what degree does this relationship differ for married and single women? Data for this study come from a 1997 survey of 530 women aged 18 to 35 in Trivandrum district of Kerala. The analysis provides strong evidence for a U-shaped relationship between household economic status (or class status) and women’s current employment status. -

Payment Locations - Muthoot

Payment Locations - Muthoot District Region Br.Code Branch Name Branch Address Branch Town Name Postel Code Branch Contact Number Royale Arcade Building, Kochalummoodu, ALLEPPEY KOZHENCHERY 4365 Kochalummoodu Mavelikkara 690570 +91-479-2358277 Kallimel P.O, Mavelikkara, Alappuzha District S. Devi building, kizhakkenada, puliyoor p.o, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 4180 PULIYOOR chenganur, alappuzha dist, pin – 689510, CHENGANUR 689510 0479-2464433 kerala Kizhakkethalekal Building, Opp.Malankkara CHENGANNUR - ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 3777 Catholic Church, Mc Road,Chengannur, CHENGANNUR - HOSPITAL ROAD 689121 0479-2457077 HOSPITAL ROAD Alleppey Dist, Pin Code - 689121 Muthoot Finance Ltd, Akeril Puthenparambil ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2672 MELPADAM MELPADAM 689627 479-2318545 Building ;Melpadam;Pincode- 689627 Kochumadam Building,Near Ksrtc Bus Stand, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2219 MAVELIKARA KSRTC MAVELIKARA KSRTC 689101 0469-2342656 Mavelikara-6890101 Thattarethu Buldg,Karakkad P.O,Chengannur, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1837 KARAKKAD KARAKKAD 689504 0479-2422687 Pin-689504 Kalluvilayil Bulg, Ennakkad P.O Alleppy,Pin- ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1481 ENNAKKAD ENNAKKAD 689624 0479-2466886 689624 Himagiri Complex,Kallumala,Thekke Junction, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1228 KALLUMALA KALLUMALA 690101 0479-2344449 Mavelikkara-690101 CHERUKOLE Anugraha Complex, Near Subhananda ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 846 CHERUKOLE MAVELIKARA 690104 04793295897 MAVELIKARA Ashramam, Cherukole,Mavelikara, 690104 Oondamparampil O V Chacko Memorial ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 668 THIRUVANVANDOOR THIRUVANVANDOOR 689109 0479-2429349 -

The Political Economy of Agrarian Policies in Kerala: a Study of State Intervention in Agricultural Commodity Markets with Particular Reference to Dairy Markets

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF AGRARIAN POLICIES IN KERALA: A STUDY OF STATE INTERVENTION IN AGRICULTURAL COMMODITY MARKETS WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO DAIRY MARKETS VELAYUDHAN RAJAGOPALAN Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Ph D Department Of Government London School O f Economics & Political Science University O f London April 1993 UMI Number: U062852 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Disscrrlation Publishing UMI U062852 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 P ”7 <ü i o ABSTRACT This thesis analyzes the nature of State intervention in agricultural commodity markets in the Indian province of Kerala in the period 1960-80. Attributing the lack of dynamism in the agrarian sector to market imperfections, the Government of Kerala has intervened both directly through departmentally run institutions and indirectly through public sector corporations. The failure of both these institutional devices encouraged the government to adopt marketing co-operatives as the preferred instruments of market intervention. Co-operatives with their decentralised, democratic structures are^ in theory, capable of combining autonomous decision-making capacity with accountability to farmer members. -

432 Impact of the Global Recession On

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IDS OpenDocs 1 Working Paper 432 IMPACT OF THE GLOBAL RECESSION ON MIGRATION AND REMITTANCES IN KERALA: NEW EVIDENCES FROM THE RETURN MIGRATION SURVEY (RMS) 2009 K.C. Zachariah S. Irudaya Rajan June 2010 2 Working Papers can be downloaded from the Centre’s website (www.cds.edu) 3 IMPACT OF THE GLOBAL RECESSION ON MIGRATION AND REMITTANCES IN KERALA: NEW EVIDENCES FROM THE RETURN MIGRATION SURVEY (RMS) 2009 K.C. Zachariah S. Irudaya Rajan June 2010 The Return Migration Survey 2009 is financed by the Department of Non-Resident Keralite Affairs (NORKA), Government of Kerala and executed by the Ministry of Overseas Indian Affairs (Government of India) Research Unit on International Migration at the Centre for Development Studies (CDS) Kerala. We are grateful to Mrs Sheela Thomas, Principal Secretary to Chief Minster and Secretary, NORKA, for her continued support. The draft version of this report was presented at an open seminar on December 1, 2009, chaired by Mrs Sheela Thomas, Secretary, NORKA and Professor D N Nararyana, CDS and Dr K N Harilal, Member, State Planning Board, Government of Kerala, as discussants. Comments received from the chairperson, discussants and participants of the seminar are gratefully acknowledged. 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Research Unit on International Migration at the Centre for Development Studies undertook this study on the request of Department of Non-Resident Keralite Affairs (NORKA), Government of Kerala. NORKA envisagaaed that the broad objective of the study should be an assessment of the impact of global recession on the emigrants from Kerala. -

Presentation Kerala

STATE POVERTY ERADICATION PLAN KERALA 0 KERALA • BASIC DATA: • Location : North latitude between 8o 18` and 12o 48` East longitude between 74o 52` and 77o 22` • Area : 38,863 sq.km. • Literacy : 93.91% Men 96.02% Women 91.98% Administrative units • No. of Districts : 14 • No. of Taluks : 63 • No. of D i s t r i c t P a nchayats : 14 • No. of Block PanchayathsLoading… : 152 • No. of Grama Panchayaths : 941 • No. of Outgrowths : 16 • No. of Census Towns : 461 • No. of Urban Agglomerations : 19 KERALA -FACTS Population as per Census 1961 2011 Total (in 000s) 16903.72 33406.06 Males -do 8361.93 16027.41 Females -do 8541.89 17378.65 Rural -do 14351 17471 Urban -do 2552 15935 Scheduled Castes -do 1422 3040 Scheduled Tribes -do 208 485 Density of Population Per Sq.Km. 435 860 Literacy Rate Percentage 55.08 94 Females per 1022 1084 Sex Ratio 1000 males STATE STATISTICS •Demographic, Socio-economic and Health profile of Kerala as comparedIndicator to India Kerala India. Total population (In crore) (Census 2011) 3.33 121.01 Decadal Growth (%) (Census 2001) 4.86 17.64 Infant Mortality rate (SRS 2011) 12 44 Maternal Mortality Rate (SRS 2007-09) 81 212 Total Fertility Rate (SRS 2011) Loading…1.8 2.4 Crude Birth Rate (SRS 2011) 15.2 21.8 Crude Death Rate (SRS 2011) 7.0 7.1 Natural Growth Rate (SRS 2011) 8.2 14.7 Sex Ratio (Census 2011) 1084 940 Child Sex Ratio (Census 2011) 959 914 0 STATE STATISTICS ● Drinking Water availability ● HH depends on Well- 62.1% ● HH depends on Tap water- 29.3% ● HH depends on Tube wells- 4.2% ● HH depends on other sources-4.4% 0 STATE STATISTICS ●HOUSE HOLDS COVERED WITH IHHL-97% ●HOUSE HOLDS WITH LPG GAS CONNECTION- 32% ●COVERAGE WITH BLACK TOPPED ROADS -78% ●HH WITH AVAILABILTY OF DRINKING WATER WITHIN PREMISES- 72.9% 0 Rural Poverty Context in the state ● Kerala which had over 40% poverty around independence has done a remarkable job in turning poverty around. -

List of Offices Under the Department of Registration

1 List of Offices under the Department of Registration District in Name& Location of Telephone Sl No which Office Address for Communication Designated Officer Office Number located 0471- O/o Inspector General of Registration, 1 IGR office Trivandrum Administrative officer 2472110/247211 Vanchiyoor, Tvpm 8/2474782 District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 2 (GL)Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471868 Thiruvananthapuram-695023 General Thiruvananthapuram District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 3 (Audit) Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471869 Thiruvananthapuram-695024 Audit Thiruvananthapuram Amaravila P.O , Thiruvananthapuram 4 Amaravila Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2234399 Pin -695122 Near Post Office, Aryanad P.O., 5 Aryanadu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0472-2851940 Thiruvananthapuram Kacherry Jn., Attingal P.O. , 6 Attingal Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2623320 Thiruvananthapuram- 695101 Thenpamuttam,BalaramapuramP.O., 7 Balaramapuram Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2403022 Thiruvananthapuram Near Killippalam Bridge, Karamana 8 Chalai Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2345473 P.O. Thiruvananthapuram -695002 Chirayinkil P.O., Thiruvananthapuram - 9 Chirayinkeezhu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2645060 695304 Kadakkavoor, Thiruvananthapuram - 10 Kadakkavoor Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2658570 695306 11 Kallara Trivandrum Kallara, Thiruvananthapuram -695608 Sub Registrar 0472-2860140 Kanjiramkulam P.O., 12 Kanjiramkulam Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2264143 Thiruvananthapuram- 695524 Kanyakulangara,Vembayam P.O. 13 -

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

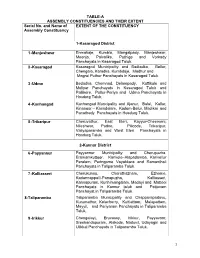

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

Average Monthly Prices of Different Varieties of Coir Yarn in Kerala

Kerala State Department of Economics & Statistics Statement showing the weekly prices of Different Varieties of Coir `.`arn Prevailing at the Coir Producing Centres in Kerala for the month of July, 2020 UNIT Rs/QtI SL Variety Centres PRICES FOR T:-1E WEEK ENDING ON No. 03-07-2020 10-07-2020 17-07-.2020 24-07-2020 31-07-2020 Average Group Averaae Kaniyapuram 9300.00 9300.00 9'300.00 9300.00 9300.00 9300.00 1 Pachallur 10750.00 Anjengo 240 12200.00 12200.00 1 : 1.00.00 12200.00 12200.00 12200.00 Thekkumbagam MANGADAN 4400.00 4400.00 4400.00 4400.00 2 Thevalakkara 4100.00 100-110 3800.00 3800.00 3800.00 3800.00 . Mangad 4600.00 4600.00 4 500.00 4600.00 4600.00 4600.00 Thekkumbagam 4400.00 4400.00 4400.00 Thevalakkara 3800.00 3800.00 3800.00 Clappana 4316.67 440',.00 4400.00 4400.00 4400.00 Muthukulam MANGADAN 4500.00 4500.00 4500.00 4500.00 4500.00 3 80 Kadavoor 4200.00 4200.00 4200.00 4200.00 4200.00 4200.00 MANUADAN 4 120 Kadavoor 8600.00 8600.00 8600.00 8600.00 8600.00 8600.00 8600.00 Clappana 4400.00 4400.00 4400.00 Alumpeedika 4400.00 4400.00 4400.00 4400.00 4400.00 4400.00 Poochakkal 5200.00 5200.00 '3200.00 5200.00 5200.00 4860.00 Pathirappally 5100.00 5100.00 -';100.00 5100.00 5100.00 '3100.00 VAIKOM YARN TRANEER 5 180 M 5200.00 5200.00 5200.00 Cherthala 4900.00 4900.00 4900.00 Poochakkal 5000.00 5000.00 `-000.00 5000.00 5000.00 4933.33 VAIKOM YARN- I HANttRmUKKO 6 160 M 4900.00 4900.00 4900.00 NERMMA(CHO 7 ODY) Kodungailur 5800.00 5800.00 5800.00 5800.00 5800.00 5800.00 5800.00 Beypore Retted- 6700.00 8 90(Handspun) Kozhikode 6700.00 6700.00 6700.00 6700.00 6700.00 6700.00 Beypore Un 9 Retted-90 Kozhikode 3500.00 3500.00 ..,500.00 3500.00 3500.00 3500.00 3500.00 KUYILJAINUY .. -

DEPARTMENT of HIGHER SECONDARY EDUCATION 9 Physics

No. EX II (2)/00001/HSE/2017 DEPARTMENT OF HIGHER SECONDARY EDUCATION HIGHER SECONDARY EXAM - MARCH 2017 LIST OF EXTERNAL EXAMINERS (Centre wise) 9 Physics District: Pathanamthitta Sl.No School Name External Examiner External's School No. Of Batches 1 03001 : GOVT. BHSS, ADOOR, BEENA G 03031 8 PATHANAMTHITTA HSST Senior (Physics) S N V HSS, ANGADICAL SOUTH, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: Ph: 04734285751, 9447117229 <=15 2 03002 : GOVT. HSS, CHITTAR, MANJU.V.L 03041 8 VADASSERIKARA, HSST Junior (Physics) K.R.P.M. HSS, SEETHATHODE, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: Ph: , 9495764711 <=15 3 03002 : GOVT. HSS, CHITTAR, THOMAS CHACKO 03010 4 VADASSERIKARA, HSST Senior (Physics) GOVT BOYS Ph: Ph: , 9446100754 HSS,PATHANAMTHITTA,PATH ANAMTHITTA 30 4 03003 : GOVT. HSS, BIJU PHILIP 03050 6 EZHUMATTOOR, HSST Senior (Physics) TECHNICAL HSS, MALLAPPALLY EAST.P.O, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: 04812401131, 9447414839 10 Ph: PATHANAMTHITTA, 689584 5 03004 : GOVT.HSS, SHEEBA VARGHESE 03045 7 KADAMMANITTA, HSST Senior (Physics) MT HSS,PATHANAMTHITTA PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: , 9447223589 10 Ph: 6 03005 : K annasa Smaraka GOVT HSS, JESSAN VARUGHESE 03016 8 KADAPRA, PATHANAMTHITTA HSST Senior (Physics) M G M HSS, THIRUVALLA, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: Ph: 04692702200, 9496212211 10 7 03006 : GOVT HSS, KALANJOOR, LEKSHMI.P.S 03009 8 PATHANAMTHITTA HSST Senior (Physics) GOVT HSS KONNI, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: Ph: , 9447086029 14 8 03007 : GOVT HSS, VECHOOCHIRA RAJIMOL P R 03026 4 COLONY, PATHANAMTHITTA HSST Senior (Physics) S N D P HSS, VENKURINJI, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: Ph: 04735266367, 9495554912 <=15 9 03008 : GOVT