Oosthuizen-2002-Landscape-History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Index of Haslingfield Site Assessment Proforma

South Cambridgeshire Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment (SHLAA) Report August 2013 Appendix 7i: Assessment of 2011 'Call for Sites' SHLAA sites Index of Haslingfield Site Assessment Proforma Site Site Address Site Capacity Page Number Site 150 Land at River Lane, Haslingfield 71 dwellings 1836 Site 163 Land at Barton Road, Haslingfield 49 dwellings 1843 SHLAA (August 2013) Appendix 7i: Assessment of 2011 'Call for Sites' SHLAA sites Group Village Haslingfield Page 1835 South Cambridgeshire Local Development Framework Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment (SHLAA) Site Assessment Proforma Proforma July 2012 Created Proforma Last July 2012 Updated Location Haslingfield Site name / Land at River Lane address Category of A village extension i.e. a development adjoining the existing village site: development framework boundary Description of promoter’s Approximately 100 houses proposal Site area 3.15ha (hectares) Site Number 150 The site is on the eastern edge of Haslingfield. The western boundary of the site is adjacent to the rear gardens of houses in Cantelupe Road. A byway - River Lane follows part of the southern boundary from Cantelupe Road before it becomes a bridleway, which Site description continues eastward alongside the River Rhee. A track follows most & context of the eastern boundary of the site. There is open countryside to the north. The flood plain of the River Cam or Rhee is to the east and south east of the site. To the south west of the site is the Haslingfield recreation ground. The site is an arable field. Current or last Agriculture use of the site Is the site Previously No Developed Land? Allocated for a non-residential use in the No current development plan? Planning None history Source of site Site suggested through call for sites SHLAA (August 2013) Appendix 7i: Assessment of 2011 'Call for Sites' SHLAA sites Group Village Page 1836 Site 150 Land at River Lane, Haslingfield Tier 1: Strategic Considerations The site is within the Green Belt. -

Rectory Farm BARRINGTON, CAMBRIDGE

RectoRy FaRm BARRINGTON, CAMBRIDGE RectoRy FaRm 6 HASLINGFIELD ROAD, BARRINGTON, CAMBRIDGE, CB22 7RG An attractive Grade II listed village house with extensive period outbuildings in a superb position next to the church Reception hall, sitting room, family room, vaulted drawing room, kitchen/dining room, rear hall, utility room, pantry, cloaks w.c. First floor – 4 double bedrooms, family bathroom, shower room, Second floor – 2 attic rooms Extensive range of traditional outbuildings comprising double-sided open bay cart lodge, former hay barn, cow shed, brick barn. Attractive gardens and grounds, ornamental pond with “Monet” style arched bridge. In all 1.27 acres Savills Cambridge Unex House, 132-134 Hills Road, Cambridge CB2 8PA Contact: James Barnett BA (Hons) MRICS [email protected] 01223 347 147 www.savills.co.uk Situation Rectory Farm is set behind the historic All Saints Parish Church in the north-eastern corner of the popular and attractive South Cambridgeshire village of Barrington. Well known for having the largest village green in England, the village has good facilities including a shop/post office, football and cricket pitches, a popular pub/restaurant and a primary school. Secondary schooling is available at Melbourn Village College and there is also a wide selection of independent schooling available in Cambridge. Further amenities are in Melbourn (4 miles), Harston (3.3 miles) and the market town of Royston, 7 miles to the south-west. More comprehensive shopping, recreational and cultural facilities are available in the high tech university city of Cambridge which is 8 miles to the north east. For the commuter there are mainline rail links to Cambridge and London King’s Cross from local stations at either Shepreth (1.8 miles) and Foxton (2 miles) to the south and direct services from Royston into London King’s Cross (from 38 minutes). -

Community Governance Review of Haslingfield Parish

Community Governance Review of Haslingfield Parish Terms of Reference www.scambs.gov.uk 1. Introduction 1.1 South Cambridgeshire District Council has resolved to undertake a Community Governance Review of the parish of Haslingfield. 1.2 This review is to address the population growth in respect of the new housing development at Trumpington Meadows: to consider whether the creation or alteration (and thus naming) of existing parish boundaries and any consequent changes to the electoral arrangements for the parish(es) should be recommended. 1.3 In undertaking this review the Council has considered the Guidance on Community Governance Reviews issued by the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government, published in April 2008, which reflects Part 4 of the Local Government and Public Involvement in HealthAct 2007 and the relevant parts of the Local Government Act 1972, Guidance on Community Governance Reviews issued in accordance with section 100(4) of the Local Government and Public Involvement in Health Act 2007 by the Department of Communities and Local Government and the Local Government Boundary Commission for England in March 2010, and the following regulations which guide, in particular, consequential matters arising from the Review: Local Government (Parishes and Parish Councils) (England) Regulations 2008 (SI2008/626). (The 2007 Act transferred powers to the principal councils which previously, under the Local Government Act 1997, had been shared with the Electoral Commission’s Boundary Committee for England.) 1.4 These Terms of Reference will set out clearly the matters on which the Community Governance Review is to focus. We will publish this document on our website and also in hard copy. -

Aroma House, 55 Harlton Road, Little Eversden

Aroma House, 55 Harlton Road, Little Eversden Aroma House, 55 Harlton Road, Little Eversden, Cambridgeshire, CB23 1HD An extended Victorian house with delightful established gardens of just under half an acre, with potential development opportunity, in this small, highly regarded south west Cambridgeshire village. Cambridge 7 miles, Royston (fast train to King's Cross) 9 miles, M11 (junction 12) 5 miles, (distances are approximate). Gross internal floor area 1,945 sq.ft (181 sq.m) plus Studio Annexe 23'1 x 12'5 (7.04m x 3.78m) Ground Floor: Reception Hall, Cloakroom, Study, Sitting Room, Dining Room, Breakfast Room, Kitchen, Utility Room. First Floor: 4 Bedrooms, 2 Bathrooms (1 En Suite). Stonecross Trumpington High Street Outside: Off Street Parking, Workshop/Store, Wonderful Mature Gardens, Studio/Annexe with Sitting Cambridge Room, Shower Room and Mezzanine Sleeping Platform. CB2 9SU t: 01223 841842 In all about half an acre. e: [email protected] f: 01223 840721 bidwells.co.uk Please read Important Notice on the last page of text Particulars of Sale Situation Little Eversden is a small, attractive village Particular features of note include: - conveniently situated about 7 miles south west of Cambridge. There is a recreation ground with play Delightful dual aspect Sitting Room with Stylish Kitchen, re-fitted in 2007 with range of area for young children within close proximity, an glazed door to terrace, fireplace with inset matching base and wall cabinet's, granite work Italian restaurant within about half a mile and an wood burning stove and twin archways to surfaces and integrated Neff appliances Indian restaurant and village hall in the neighbouring adjoining Dining Room. -

24 Haslingfield Road, Harlton, CB23 1ER Prices From

Plot 1 & 2, 22 - 24 Haslingfield Road, Harlton, CB23 1ER Prices from £1.35m rah.co.uk 01223 800860 A SUPERIOR INDIVUDAL DETACHED 5-BEDROOM FAMILY HOME SET IN PART WOODED GROUNDS OF AROUND ½ ACRE WITH PICTURESQUE VIEWS OVER OPEN COUNTRYSIDE Reception hall – sitting room – living room – cloakroom and WC – Open-plan kitchen / dining / family room – utility room - garden room – gallery landing - master suite with dressing room and en-suite shower – two en-suite bedrooms – two further double bedrooms - family bathroom – underfloor heating to the ground floor – double garage – large garden – 10 year warranty Location: Harlton is a charming village situated within pretty countryside to the south west of the University City of Cambridge. With a public house, parish church and a range of clubs and societies which operate within the village, Harlton is a cherished village to live. Primary schooling together with a range of shopping facilities are available in the neighbouring villages of Haslingfield and Harston whilst a wider range of amenities are available in Great Shelford. The village lies approximately seven miles away from Cambridge with access for the M11 motorway (junction 12) a few minutes-drive away and a short drive to both Foxton and Shepreth train stations, both operated by Great Northern line to Cambridge and London Kings Cross. The Property: Set aside in this beautiful village, the property is one of a pair of exceptional detached 5-bedroom homes offering well designed bright and spacious accommodation set across two floors and set in around 1/2 an acre, with views over open countryside. The property is built to an outstanding design with modern day family living in mind. -

Helpline - 0300 666 9860

Covid-19 Services Update November 2020 Below is a summary of all of our services as at 12th November. Circumstances change quickly, so please contact us for the latest information. We regularly post to social media, please follow us @ageukcap on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn Age UK Cambridgeshire and Peterborough HELPLINE - 0300 666 9860 Information Services Information & Advice We provide free confidential information so older people and their carers can make informed decisions on matters such as benefits, housing, care choices and health. We have a rage of free factsheets and guides. Open Monday – Friday 10am – 2pm Tel: 0300 666 9860, outside of these hours the line transfers to the national Age UK advice line which is open 8am – 8pm. Visiting Support Service for Older People (VSSOP) We can give free extra support when most needed, particularly when experiencing a difficult period, such as bereavement, ill health, financial or housing concerns, negotiating complex statutory situations. Operating in East Cambridgeshire, Fenland and Huntingdonshire. Currently also in Peterborough as a pilot. During Covid Community Hubs have been suspended. Remote support is continuing. Girton Older Residents Co-ordinator We work alongside statutory, voluntary and community groups in the South Cambridgeshire village of Girton to support existing groups, linking residents with appropriate services. During Covid the coordinator has continued with our free support in arranging outdoor meetings with residents. Social Opportunities Our Day Centres and Friendship Clubs were suspended in March, to comply with government Covid guidelines. However support has continued, please see below: Friendship Clubs We support a number of clubs in and around the Peterborough area, with more clubs being developed and introduced across Cambridgeshire. -

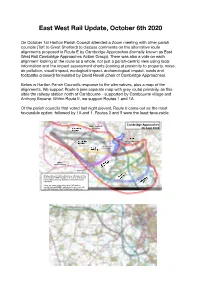

East West Rail Update Oct

East West Rail Update, October 6th 2020 On October 1st Harlton Parish Council attended a Zoom meeting with other parish councils (Toft to Great Shelford) to discuss comments on the alternative route alignments proposed in Route E by Cambridge Approaches (formally known as East West Rail Cambridge Approaches Action Group). There was also a vote on each alignment looking at the route as a whole, not just a parish-centric view using local information and the impact assessment charts (looking at proximity to property, noise, air pollution, visual impact, ecological impact, archaeological impact, roads and footpaths crossed) formulated by David Revell (chair of Cambridge Approaches). Below is Harlton Parish Council’s response to the alternatives, plus a map of the alignments. We support Route 6 (see separate map with grey route) primarily, as this sites the railway station north of Cambourne - supported by Cambourne village and Anthony Browne. Within Route E, we support Routes 1 and 1A. Of the parish councils that voted last night (seven), Route 6 came out as the most favourable option, followed by 1A and 1. Routes 3 and 5 were the least favourable. Cambridge Approaches EWR's 'Option E' Boundary 26 Sept 2020 Extension to Trumpington Park & Ride Industrial effluent disposal plant MRAO exclusion zone Tu n n e ls All alternative corridors shown are indicative of the general route EWR may take in this area and should not be taken as being definitive of the limits of an alignment. There are many alternatives that EWR may be considering and EWR’s options to be presented in Jan 2021 may well differ from those shown here. -

South Cambridgeshire District Council – Caldecote Ward Councillor's

South Cambridgeshire District Council – Caldecote Ward (comprises the Parishes of Caldecote, Childerley, Kingston, Bourn, Longstowe & Little Gransden) Councillor’s Monthly Report – May 2021 This report of previous month events is for all the Ward, so please be aware that some of the content may not be relevant to your particular Parish. General Please contact me with comments, questions, problems, reports, suggestions or complaints to do with SCDC services. These are housing need, housing repairs for council tenants, planning, benefits, council tax, bin collection, environmental health issues etc. Don’t fight on your own. I am available to help you to get the best outcome possible for your situation. If you have time to spare – check out articles on my blog http://www.TumiHawkins.org.uk. What I post on there is my view and not LibDem or South Cambs official policy unless I state that it is. IMPORTANT REMINDERS These are items in my previous reports that require action due to time limitations or important. 1. Rapid Covid Tests If you need a rapid test, then remember a Rapid Testing Centre is available at The Hub, High Street, Cambourne, CB23 6GW, 8am-8pm, Mon-Sat. It is for key workers and people who are unable to work from home who are showing no symptoms to get tested if they are worried. You can book test at https://www.cambridgeshire.gov.uk/rapidtesting COVID19 UPDATE As of today there are 22 people in hospital with Covid in Cambridgeshire with 3 in Addenbrookes. This is a huge improvement and will of course allow our hospitals get back to treating people with other conditions many of which are now very urgent. -

47 Clare Drive, Highfields Caldecote, Cambridge, CB23 7GB Guide Price

47 Clare Drive, Highfields Caldecote, Cambridge, CB23 7GB Guide Price £425,000 Freehold rah.co.uk 01223 800860 AN ATTRACTIVE MODERN DOUBLE FRONTED DETACHED FAMILY RESIDENCE BEAUTIFULLY PRESENTED THROUGHOUT, SET WITHIN A GENEROUS CORNER PLOT BOASTING A SOUTH FACING GARDEN AND LOCATED WITHIN THE COMBERTON VILLAGE COLLEGE CATCHMENT AREA LOCATION Highfields Caldecote derives its name from the two parishes that make up the combined village which is located approximately 7 miles west of Cambridge and is situated off the A428 Bedford Road. Its convenient location allows easy access to the City of Cambridge, M11, A1 and A14. Within Caldecote is a primary school, Parish Church and village shop, a wider range of facilities are available in nearby Cambourne (3 miles) including a Morrisons supermarket, doctors surgery, day care nursery and hotel. In addition the village falls within the catchment area for the highly regarded and sought after Comberton Village College. It is a village also surrounded by glorious open countryside over which there are many fine walks. Bourn and Comberton Golf Clubs are also about 2 miles away. THE PROPERTY The property occupies a generous corner plot and recently the front and side garden have been professionally landscaped and enclosed by a new picket fence. The property boasts a good energy performance certificate rating largely due to the newly fitted Vaillant condensing boiler (1 year old) and an expanse of Photovoltaic Solar Panels which makes a return of over £1,000 per annum. The entrance hall boasts two fitted storage cupboards, stairs to the first floor and a cloakroom WC. -

South Cambridgeshire District Council – Harston & Comberton Ward Report to Haslingfield Parish Council July 2021

South Cambridgeshire District Council – Harston & Comberton Ward Report to Haslingfield Parish Council July 2021 Covid Update Rates of Covid-19 in Cambridgeshire have risen sharply and they continue to rise. At the time of writing, there are 92 cases per 100,000 across Cambridgeshire, which is an 85 increase on last week. There is particular concern about the rising rates of Covid-19 in Cambridge and South Cambridgeshire. Again at the time of writing, there are 216 cases per 100,000 in Cambridge and 101 cases in South Cambridgeshire, with most cases being seen in 18 to 30-year-olds. Hospital admissions remain fairly low and there has been one death in the past month. What we are seeing in parts of Cambridgeshire is very similar to the rest of the country, in that the Delta variant, which we know to be much easier to pass on, is accounting for the rise in cases of Covid-19. There is a big push to promote testing amongst the 18-30 year olds, including people without symptoms, as you are no doubt aware the virus can spread without any symptoms showing. Alongside testing there is a race against time to ensure as many people as possible take up their first and second doses of vaccine before restrictions are lifted on the 19th July. The lifting of restrictions could further fuel the spread of the virus, exposing people at high risk, to infection. Cambridge South-West Travel Hub We understand the plans for the Cambridge South West Travel Hub go before the County Council Planning Committee on 29th July. -

Caldecote Village Design Guide

Caldecote Village Design Guide Supplementary Planning Document Consultation Draft April 2019 Aerial photograph of Caldecote with the parish boundary highlighted. Page 2 Contents Page Foreword 4 1. Introduction 5 2. About Caldecote 6 3. Community Input 8 4. Village Character 10 5. Routes 14 6. Integrating new development 16 7. Infll development at Highfelds 18 8. Drainage and ditches 20 9. Village edges 22 Note to reader The draft Caldecote Village Design Guide supplements the new Local Plan policies on high quality design, distinctive local character and placemaking. Technically the SPD will be a material consideration in the determination of planning applications in Caldecote and it has been prepared in collaboration with community representatves. The outcome of the current consultation will help us to further refne the Village Design Guide before it is considered for adoption by South Cambridgeshire District Council. It is important to understand that the SPD cannot make new planning policy, or allocate sites for development and must be in conformity with the policies of the South Cambridgeshire Local Plan. The draft Caldecote Village Design Guide SPD is being consulted upon along with the following accompanying documents: • Sustainability Appraisal Screening Report • Habitats Regulations Screening Report • Equality Impact Assessment • Consultation Statement Consultation is for six weeks and runs between 15 April-31 May 2019. These documents can be viewed online at www.southcambs.gov.uk/villagedesignstatements and will be available for inspection at South Cambridgeshire District Council offces at South Cambridgeshire Hall, Cambourne, Cambridge CB23 6EA (8.30am to 5pm Monday-Friday) Page 3 Foreword South Cambridgeshire is a district of diverse and distinctive villages, as well as being a high growth area. -

Green Belt Study 2002

South Cambridgeshire District Council South Cambridgeshire Hall 9-11 Hills Road Cambridge CB2 1PB CAMBRIDGE GREEN BELT STUDY A Vision of the Future for Cambridge in its Green Belt Setting FINAL REPORT Landscape Design Associates 17 Minster Precincts Peterborough PE1 1XX Tel: 01733 310471 Fax: 01733 553661 Email: [email protected] September 2002 1641LP/PB/SB/Cambridge Green Belt Final Report/September 2002 CONTENTS CONTENTS SUMMARY 1.0 INTRODUCTION 2.0 CAMBRIDGE GREEN BELT: PLANNING CONTEXT 3.0 METHODOLOGY 4.0 BASELINE STUDIES Drawings: 1641LP/01 Policy Context: Environmental Designations 1641LP/02 Policy Context: Cultural and Access Designations 1641LP/03 Topography 1641LP/04 Townscape Character 1641LP/05 Landscape Character 1641LP/06 Visual Assessment 5.0 SETTING AND SPECIAL CHARACTER Drawings: 1641LP/07 Townscape and Landscape Analysis 1641LP/08 Townscape and Landscape Role and Function 6.0 QUALITIES TO BE SAFEGUARDED AND A VISION OF THE CITY Drawings: 1641LP/09 Special Qualities to be Safeguarded 1641LP/10 A Vision of Cambridge 7.0 DETAILED APPRAISAL EAST OF CAMBRIDGE Drawings: 1641LP/11 Environment 1641LP/12 Townscape and Landscape Character 1641LP/13 Analysis 1641LP/14 Special Qualities to be Safeguarded 1641LP/15 A Vision of East Cambridge 8.0 CONCLUSIONS Cover: The background illustration is from the Cambridgeshire Collection, Cambridge City Library. The top illustration is the prospect of Cambridge from the east and the bottom illustration is the prospect from the west in 1688. 1641LP/PB/SB/Cambridge Green Belt Final Report/September 2002 SUMMARY SUMMARY Appointment and Brief South Cambridgeshire District Council appointed Landscape Design Associates to undertake this study to assess the contribution that the eastern sector of the Green Belt makes to the overall purposes of the Cambridge Green Belt.