Beasts of Flight Brian Wood San Jose State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

Country Update

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS JULY 15, 2019 | PAGE 1 OF 20 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] Combs, Shelton Own Charts Luke Combs On Fire As He >page 4 Joins The Grand Ole Opry Country’s Good Works On Display When Luke Combs made his 16th Grand Ole Opry appearance moment, like seeing what each day that I wake up to holds,” >page 10 on June 11, John Conlee interrupted his set — along with Craig he says. “But in the last couple of weeks, I’ve really started to Morgan and Chris Janson — to touch Combs on the shoulder. put a lot back in the tank as far as, what’s the next steps of the “We just want a little bit of your heat,” said Conlee. process? How do we expand on what we’re doing?” The heat boiled up into tears The Opry thing might be helping CMA Fest Duets within seconds after Combs was that process. Membership brings a With ABC asked to join the cast of the WSM-AM certain stability — Brooks has been >page 11 Nashville show, a membership that with the Opry for more than 25 will become official with his July 16 years, Ricky Skaggs has been on induction. the roster nearly 40 years, and Bill It comes, as Conlee noted, with Anderson will celebrate 60 years Live News: Brown, Combs in the midst of an enviable on the team in 2021. It’s natural Urban, Bryan hot streak. His debut album, This for Combs to assess how his future >page 11 One’s for You, is spending its 41st might play out in that context. -

The Rhetoric of the Benign Scapegoat: President Reagan and the Federal Government

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2000 The Rhetoric of the Benign Scapegoat: President Reagan and the Federal Government. Stephen Wayne Braden Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Braden, Stephen Wayne, "The Rhetoric of the Benign Scapegoat: President Reagan and the Federal Government." (2000). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7340. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7340 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Online Streaming and the Chart Survival of Music Tracks

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Kaimann, Daniel; Tanneberg, Ilka; Cox, Joe Article — Published Version “I will survive”: Online streaming and the chart survival of music tracks Managerial and Decision Economics Provided in Cooperation with: John Wiley & Sons Suggested Citation: Kaimann, Daniel; Tanneberg, Ilka; Cox, Joe (2020) : “I will survive”: Online streaming and the chart survival of music tracks, Managerial and Decision Economics, ISSN 1099-1468, Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, Vol. 42, Iss. 1, pp. 3-20, http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mde.3226 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/230292 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von -

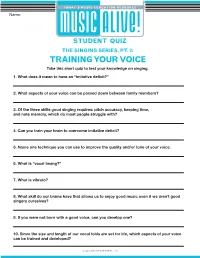

TRAINING YOUR VOICE Take This Short Quiz to Test Your Knowledge on Singing

TODAY’S MUSIC EDUCATION RESOURCE Name: STUDENT QUIZ THE SINGING SERIES, PT. 2: TRAINING YOUR VOICE Take this short quiz to test your knowledge on singing. 1. What does it mean to have an “imitative deficit?” 2. What aspects of your voice can be passed down between family members? 3. Of the three skills good singing requires: pitch accuracy, keeping time, and note memory, which do most people struggle with? 4. Can you train your brain to overcome imitative deficit? 5. Name one technique you can use to improve the quality and/or tone of your voice. 6. What is “vocal twang?” 7. What is vibrato? 8. What skill do our brains have that allows us to enjoy good music even if we aren’t good singers ourselves? 9. If you were not born with a good voice, can you develop one? 10. Since the size and length of our vocal folds are set for life, which aspects of your voice can be trained and developed? © 2018 IN TUNE PARTNERS, LLC TODAY’S MUSIC EDUCATION RESOURCE Name: STUDENT QUIZ THEATER THEMES Take this short quiz to test your knowledge about musicals about music. 1. Name four performances mentioned in the article. 2. What is special about a musical about music? 3. What is a “jukebox musical?” 4. Whose music is featured in the musical, We Will Rock You? 5. What decade is the music in Rock of Ages from? 6. What is the title of the musical created about the life and times of Carole King? 7. What happens in the story of The Band’s Visit? 8. -

Oliver Stone's Nixon: Politics on the Edge of Darkness IAN SCOTT

Oliver Stone's Nixon: Politics on the Edge of Darkness IAN SCOTT In the introduction to his controversial book, The Ends of Power , former White House Chief of Staff, H.R. Haldeman describes Watergate as being an expression «of the dark side of President Nixon» 1. Later in the book Haldeman cites former Special Counsel Charles Colson as a key man who «encouraged the dark impulses in Nixon's mind» 2. Stephen Ambrose has written that Nixon «never abandoned his black impulses to lash out at the world...», while Henry Kissinger offered the view that «the thoughtful analytical side of Nixon was most in evidence during crises, while periods of calm seemed to unleash the darker passions of his nature» 3. Christopher Wilkinson -talking directly about Oliver Stone's film-has focused on the movie's analogy of a «beast» that «also became a metaphor for the dark side of Nixon himself» 4. Wherever you look in the vast array of literature on the life and times of President Richard Nixon, as sure as you are to hear the description «Shakespearean tragedy», so the notions of dark and brooding forces are never far away, following in the shadows of the man. As many have pointed out, however, Nixon's unknown blacker side was not merely a temperamental reaction, not only a protective camouflage to deflect from the poor boy made good syndrome that he was proud about and talked a great deal of, but always remained an Achilles heel in his own mind; no the concealment of emotional energy was tied up in the fascination with life and beyond. -

For Your Ears Only Winter 2019 - 2020

For Your Ears Only Winter 2019 - 2020 Welcome to the latest edition of For Your Ears Only, packed with an abundance of titles to help you choose your next books, that will keep you company through the rest of the winter. As we enter into the new year you may want to discover some different authors, so how about trying the two new books by cosy crime author T P Fielden, or what about Elaine Roberts with her first family saga book called “The Foyles Bookshop Girls”. Then there is a book to take a chance on in the form of “Little” by Edward Carey, a fictional account of the life of Madame Tussaud, or embark on a quest to find out more about the universe in “The Planets” by Brian Cox and Andrew Cohen. You may order any of the books in this FYEO by using the enclosed order form. Alternatively you can email us at [email protected] or telephone Membership Services on 01296 432339. Please be aware that any books you ask for will be added on to the end of your request list, so if you have a long list it may be some time before you get them. If you would like to talk about your requests list, then please get in touch with Membership Services. Happy reading from the Editorial Team Emma Scott, Janet Connolly and Denise James Contents page 02 Recent Additions to the library - Fiction page 59 Recent additions to the library – Non-Fiction p1 RECENT ADDITIONS TO THE LIBRARY X - Denotes Sex, Violence or Strong Language Time - Approximate listening time All Books Available in the European Union and the UK All Books are available on MP3 CD, USB memory stick and can be streamed via Calibre’s website Fiction 20TH CENTURY CLASSICS 13424 EVA TROUT By Elizabeth Bowen Narrator Clare Francis Orphaned at a young age, Eva Trout has found a home of sorts with her former schoolteacher, Iseult Arbles. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 114 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 114 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 161 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, JUNE 18, 2015 No. 98 Senate The Senate met at 9:30 a.m. and was heard this morning in my morning MORNING BUSINESS called to order by the President pro briefing and then the news accounts of The PRESIDING OFFICER. Under tempore (Mr. HATCH). this sickening revelation of what took the previous order, the Senate will be f place in South Carolina last night. in a period of morning business for 1 Think about this. The sanctity of a PRAYER hour, with Senators permitted to speak house of worship was violated as a gun- therein, with the time equally divided, The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- man opened fire in the historically fered the following prayer: with the majority controlling the first Black Emanuel AME Church in half and the Democrats controlling the Let us pray. Charleston, SC. Eternal God, You are perfect in wis- final half. dom and goodness. Thank You for the We know now at least nine people are Mr. REID. Mr. President, I suggest great and mysterious opportunities of dead, and others, of course, are hurt. I the absence of a quorum. our lives. Empower our Senators to don’t know how to describe it. This in- The PRESIDING OFFICER. The seize these opportunities, thereby, ful- dividual was like a wolf in sheep’s clerk will call the roll. filling Your purposes for their lives in clothing. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} on the Edge of Darkness Kindle

ON THE EDGE OF DARKNESS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Barbara Erskine | 496 pages | 19 Feb 2009 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007288656 | English | London, United Kingdom On the Edge of Darkness PDF Book The characters. Edge of Darkness is a British television drama serial produced by BBC Television in association with Lionheart Television International and originally broadcast in six fifty-five-minute episodes in late I loved it because Peterson's auth Andrew Peterson is an amazing story teller. Unlike Middle Earth, the names are goofy and seem like a long series of smart jokes. Taglines: Few escape justice. This review has been hidden because it contains spoilers. Thomas realizes he needs to take his daughter to the hospital. View all 6 comments. I personally Think it may have needed to go on for another chapter or 2 for example "Life after Brid" as felt there were elements missing to the stories finale. We live in a magical place we call the Warren, just south of Nashville. Burning Emma's clothing in his backyard, Craven suddenly draws his weapon and turns to find Jedburgh, a British "consultant", casually sitting in his backyard. This article is about the television drama. Other editions. Despite the length of the book we never see any depth in the two "wizard" characters who battle it out in the end over the two lovers and the two women who are collateral damage of their affair. Gerd Bjarnesen Ruth Gordon Not one of her best And if Christians are looking for a book that they don't have to worry ab …more It might also be because the author is mostly known for his Christian music. -

The Anthropology of Dark Tourism

CCEERRSS Centre for Ethnicity & Racism Studies The anthropology of dark tourism Exploring the contradictions of capitalism Dr Maximiliano Korstanje February 2015 Introduction Dark tourism is a phenomenon widely studied over the last decades. More substantial research has been advanced as fieldwork in dark tourism sites (Seaton, 1996; Stone, 2012; Shapley, 2005; Korstanje & Ivanov, 2012; Korstanje, 2011b). However, such studies focused on methodologies that use tourists as the analysis’ starting point. Sometimes, interviewees do not respond with honesty, or simply are not familiar with the basis of their own behaviour. In Latin America people in some regions with histories of mass-death are reluctant to accept tourism as their main profitable resource. Some destinations exploit death as the site’s primary attraction, whereas other ones develop a negative attitude towards tourists. A more helpful way to advance this discussion, as relevant literature suggests, is that dark tourism is defined by the presence of “thanaptosis”: the possibility to understand one’s own (future) end through the death of others. This allows us to think of dark tourism as a subtype of heritage, even connect it to pilgrimage (Poria, 2007; Seaton, 1996; Cohen 2011). Yet, even these studies ignore the real roots of the debate on “thanatopsis” and its significance for configuring the geography of dark sites. 1 The concept of “thanatopsis”, which was misunderstood by some tourism scholars, such as Seaton or Sharpley, was originally coined by the American poet William Cullen Bryant (1817) to refer to the anticipation of one’s own death through the eyes of others. Those who have read Bryant’s poem will agree that the death of other people make us feel better because we avoided temporarily our own end. -

Death and Mourning Rituals Fact Sheet

Workplace FACT SHEET Death and Mourning Rituals This document lays out basic information about the death, funeral rites, and post-death practices of eight major religious traditions, drawing from Tanenbaum’s online resource, Religion at Work. Addi- tionally, this resource has been updated to include anticipated adjustments due to social distancing on death and mourning rituals and their impact on the workplace. This is by no means an exhaus- tive resource, but is intended to offer an introductory overview to this information. Please keep in mind that there is great diversity within and among religious communities, so colleagues may prac- tice and believe in ways that are not covered in this resource. MOURNING & COVID-19 Adjusted Rules: Burials and Cremations Around the world adjustments are being made to centuries old traditions around burial and crematoria practices, across religions. Depending on the country, burials and cremations are required to be conducted within 12 hours of a loved ones’ passing or delayed to a much later date. Some countries are specifying the location of the burial or requiring that remains be picked up only at scheduled times. Practices such as loved ones cleaning the recently deceased body, sharing a shovel to put dirt on the de- ceased’s coffin, and funeral pyres are no longer doable as they used to be. Furthermore, burial or crema- tion options may be even more limited for those already facing economic hardships to then have to man- age and take on an unexpected death and associated costs. Time Off: Delayed Mourning Rituals For many, traditional group gatherings, whether in a home, house of worship, or within the town, are strongly discouraged, both for funerals and mourning practices. -

The Development of the British Conspiracy Thriller 1980-1990

The Development of the British Conspiracy Thriller 1980-1990 Paul S. Lynch This thesis is submitted to the University of Hertfordshire in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. January 2017 Abstract This thesis adopts a cross-disciplinary approach to explore the development of the conspiracy thriller genre in British cinema during the 1980s. There is considerable academic interest in the Hollywood conspiracy cycle that emerged in America during the 1970s. Films such as The Parallax View (Pakula, 1975) and All the President’s Men (Pakula, 1976) are indicative of the genre, and sought to reflect public anxieties about perceived government misdeeds and misconduct within the security services. In Europe during the same period, directors Costa-Gavras and Francesco Rosi were exploring similar themes of state corruption and conspiracy in films such as State of Siege (1972) and Illustrious Corpses (1976). This thesis provides a comprehensive account of how a similar conspiracy cycle emerged in Britain in the following decade. We will examine the ways in which British film-makers used the conspiracy form to reflect public concerns about issues of defence and national security, and questioned the measures adopted by the British government and the intelligence community to combat Soviet subversion during the last decade of the Cold War. Unlike other research exploring espionage in British film and television, this research is concerned exclusively with the development of the conspiracy thriller genre in mainstream cinema. This has been achieved using three case studies: Defence of the Realm (Drury, 1986), The Whistle Blower (Langton, 1987) and The Fourth Protocol (MacKenzie, 1987).