Online Streaming and the Chart Survival of Music Tracks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daft Punk Collectible Sales Skyrocket After Breakup: 'I Could've Made

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; BrettENTERTAINMENT Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth AirplayFEBRUARY 25, 2021 Page 1 of 37 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE Daft Punk Collectible Sales Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal Music Group Nashville), debutsSkyrocket at No. 1 on Billboard’s lion audience After impressions, Breakup: up 16%). Top Country• Spotify Albums Takes onchart dated April 18. In its first week (ending April 9), it earned$1.3B 46,000 in equivalentDebt album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cording• Taylor to Nielsen Swift Music/MRCFiles Data. ‘I Could’veand total Made Country Airplay No.$100,000’ 1 as “Catch” (Big Machine Label Group) ascends SouthsideHer Own marks Lawsuit Hunt’s in second No. 1 on the 2-1, increasing 13% to 36.6 million impressions. chartEscalating and fourth Theme top 10. It follows freshman LP BY STEVE KNOPPER Young’s first of six chart entries, “Sleep With- MontevalloPark, which Battle arrived at the summit in No - out You,” reached No. 2 in December 2016. He vember 2014 and reigned for nine weeks. To date, followed with the multiweek No. 1s “In Case You In the 24 hours following Daft Punk’s breakup Thomas, who figured out how to build the helmets Montevallo• Mumford has andearned Sons’ 3.9 million units, with 1.4 Didn’t Know” (two weeks, June 2017), “Like I Loved millionBen in Lovettalbum sales. -

Lieder, Die Ein Deutschlehrer Braucht

Lieder, die ein Deutschlehrer braucht DOLORES RODRÍGUEZ CEMILLÁN Escuela Oficial de Idiomas de Fuenlabrada, Madrid s gibt viele und wichtige Gründe zum Einsatz Beispiele und Quellen von Liedern im Deutschunterricht: Lieder sind vor Allem authentische Texte, man kann mit Von der unten vorgestellten Liste sind bestimmte Lieder unt - ihnen die vier Fertigkeiten trainieren, sie er - entbehrlich und sehr empfehlenswert: so ist «1,2 Polizei« von leichtern die Ausprache und sie vermitteln Lan - Modo ist immer ein Erfolg, wenn man die Zahlen von 1 bis deskunde. Man kann Lieder fast für jede Un - 10 beibringen will. Oder «MFG» von den Fantastischen Vier terrichts− oder Lehrwerkseinheit gezielt ein - ist ein Rap-Hit zum üben des Alfabets und der Abkürzungen. setzen, da sie einen kreativen und motivieren - Immer wieder einsetzbar sind auch die deutschen Versionen den Umgang mit der deutschen Sprache er - von den Beatles, «Sie liebt dich» und «Komm, gib mir deine lauben und emotionale und kommunikative Hand», zwei bekannte Erfolge, mit denen man sehr schön Per - Kompetenzen ansprechen. Mit Liedern und sonalpronomen im Akkusativ und Dativ üben kann. Gram - Musik verbessern sich die kommunikativen matisch sehr interessant ist auch das Lied «Durch den Mon - und sozialen Kompetenzen der Lerner; man sun«, von Tokio Hotel, da hier viele Präpositionen kontextua - regt sie zu Leistungsbereitschaft an und hat lisiert vorkommen. Thematisch und landeskundlich gesehen, die Möglichkeit, Konzentrationsschwächen zu kompensie - ist das Lied «Deutschland» von den -

Smart Speakers & Their Impact on Music Consumption

Everybody’s Talkin’ Smart Speakers & their impact on music consumption A special report by Music Ally for the BPI and the Entertainment Retailers Association Contents 02"Forewords 04"Executive Summary 07"Devices Guide 18"Market Data 22"The Impact on Music 34"What Comes Next? Forewords Geoff Taylor, chief executive of the BPI, and Kim Bayley, chief executive of ERA, on the potential of smart speakers for artists 1 and the music industry Forewords Kim Bayley, CEO! Geoff Taylor, CEO! Entertainment Retailers Association BPI and BRIT Awards Music began with the human voice. It is the instrument which virtually Smart speakers are poised to kickstart the next stage of the music all are born with. So how appropriate that the voice is fast emerging as streaming revolution. With fans consuming more than 100 billion the future of entertainment technology. streams of music in 2017 (audio and video), streaming has overtaken CD to become the dominant format in the music mix. The iTunes Store decoupled music buying from the disc; Spotify decoupled music access from ownership: now voice control frees music Smart speakers will undoubtedly give streaming a further boost, from the keyboard. In the process it promises music fans a more fluid attracting more casual listeners into subscription music services, as and personal relationship with the music they love. It also offers a real music is the killer app for these devices. solution to optimising streaming for the automobile. Playlists curated by streaming services are already an essential Naturally there are challenges too. The music industry has struggled to marketing channel for music, and their influence will only increase as deliver the metadata required in a digital music environment. -

Country Update

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS JULY 15, 2019 | PAGE 1 OF 20 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] Combs, Shelton Own Charts Luke Combs On Fire As He >page 4 Joins The Grand Ole Opry Country’s Good Works On Display When Luke Combs made his 16th Grand Ole Opry appearance moment, like seeing what each day that I wake up to holds,” >page 10 on June 11, John Conlee interrupted his set — along with Craig he says. “But in the last couple of weeks, I’ve really started to Morgan and Chris Janson — to touch Combs on the shoulder. put a lot back in the tank as far as, what’s the next steps of the “We just want a little bit of your heat,” said Conlee. process? How do we expand on what we’re doing?” The heat boiled up into tears The Opry thing might be helping CMA Fest Duets within seconds after Combs was that process. Membership brings a With ABC asked to join the cast of the WSM-AM certain stability — Brooks has been >page 11 Nashville show, a membership that with the Opry for more than 25 will become official with his July 16 years, Ricky Skaggs has been on induction. the roster nearly 40 years, and Bill It comes, as Conlee noted, with Anderson will celebrate 60 years Live News: Brown, Combs in the midst of an enviable on the team in 2021. It’s natural Urban, Bryan hot streak. His debut album, This for Combs to assess how his future >page 11 One’s for You, is spending its 41st might play out in that context. -

Beyond Napster, Beyond the United States: the Technological and International Legal Barriers to On-Line Copyright Enforcement

NYLS Law Review Vols. 22-63 (1976-2019) Volume 46 Issue 1 Judge Jon. O. Newman: A Symposium Celebrating his Thirty Years on the Federal Article 10 Bench January 2003 BEYOND NAPSTER, BEYOND THE UNITED STATES: THE TECHNOLOGICAL AND INTERNATIONAL LEGAL BARRIERS TO ON-LINE COPYRIGHT ENFORCEMENT Jeffrey L. Dodes Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/nyls_law_review Part of the Communications Law Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, Internet Law Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal History Commons, Litigation Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation Jeffrey L. Dodes, BEYOND NAPSTER, BEYOND THE UNITED STATES: THE TECHNOLOGICAL AND INTERNATIONAL LEGAL BARRIERS TO ON-LINE COPYRIGHT ENFORCEMENT, 46 N.Y.L. SCH. L. REV. (2002-2003). This Note is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Law Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. \\server05\productn\N\NLR\46-1-2\NLR102.txt unknown Seq: 1 11-FEB-03 13:48 BEYOND NAPSTER, BEYOND THE UNITED STATES: THE TECHNOLOGICAL AND INTERNATIONAL LEGAL BARRIERS TO ON-LINE COPYRIGHT ENFORCEMENT I. INTRODUCTION Courts in the United States and throughout the world are faced with great challenges in adjudicating legal conflicts created by the rapid development of digital technologies. The proliferation of new technologies that allow for fast, reliable and widespread transmission of digital files has recently created a swell of litigation and media cover- age throughout the world. Copyright -

The Use of Music Technologies in Field Education Courses and Daily Lives of Music Education Department Students (Sample of Atatürk University)∗

Universal Journal of Educational Research 6(5): 1005-1014, 2018 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/ujer.2018.060521 The Use of Music Technologies in Field Education Courses and Daily Lives of Music Education ∗ Department Students (Sample of Atatürk University) Gökalp Parasiz Department of Fine Arts Education, Necatibey Education Faculty, Balıkesir University, Balıkesir, Turkey Copyright©2018 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract Technology-oriented tools/devices have long situations. been an indispensable part of music as well as music Technology and education are branches of science in education for many years. It is of great importance in music their own right and they have different theories and education for students and teachers and the future of music techniques but they are used together to improve quality in to follow closely and use the technological developments learning and teaching environments. This use reveals a new in the present age in which technology directs the future. discipline, namely education technology [10]. Today, both The aim of this research is to determine the use of information content and technological developments are technology and music technologies in music training rapidly changing and spreading. These formations students' field education courses in general and to naturally affect learning-teaching styles [16]. The determine the contribution of technology in both learning development of technology affects both the structure of the and application fields both individually and in general education system and the learning-teaching activities. -

Analýza Nejposlouchanějších Skladeb Na Serveru Youtube.Com

Masarykova univerzita Pedagogická fakulta ANALÝZA NEJPOSLOUCHANĚJŠÍCH SKLADEB NA SERVERU YOUTUBE.COM Bakalářská práce Brno 2017 Autor: Vedoucí bakalářské práce: Jakub Šindelka doc. PhDr. Marek Sedláček, Ph.D. Anotace Název práce: Analýza nejposlouchanějších skladeb na serveru YouTube.com Title: The analysis of the most listened compositions on YouTube.com Tato práce se zabývá analýzou devatenácti nejposlouchanějších hudebních skladeb na serveru YouTube.com, které byly uploadovány v roce 2014 a později. Seznam je aktuální k datu 1. 7. 2016, práce se tedy zabývá skladbami, které byly nejpopulárnější na serveru YouTube od začátku roku 2014 do poloviny roku 2016. U skladeb je zkoumán jejich žánr, délka, tempo, harmonie, struktura a další charakteristiky, práce se zabývá rovněž interprety těchto skladeb a jejich životem, tvorbou a uměleckou kariérou. Závěrečná část práce je věnována vyhodnocení toho, jaké znaky jsou u skladeb nejčastější a nejtypičtější. Okrajově se práce zabývá rovněž historií a principem fungování serveru YouTube. This thesis is focused on the analysis of the nineteen most listened music compositions on YouTube.com, which were uploaded in 2014 or later. The list is relevant to 1. 7. 2016, therefore the point of interest of the thesis are composions, which were the most popular in the period since the beginning of 2014 to the half of 2016. The aspects of compositions which are analyzed are their genre, lenght, tempo, harmony, structure and other characteristics, thesis also tries to comprehend the life, artworks and carrier of interprets of the compositions. The goal of the final part of this thesis is to evaluate which characteristics of the compositions are the most frequent and the most typical ones. -

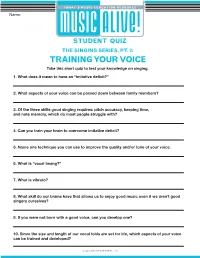

TRAINING YOUR VOICE Take This Short Quiz to Test Your Knowledge on Singing

TODAY’S MUSIC EDUCATION RESOURCE Name: STUDENT QUIZ THE SINGING SERIES, PT. 2: TRAINING YOUR VOICE Take this short quiz to test your knowledge on singing. 1. What does it mean to have an “imitative deficit?” 2. What aspects of your voice can be passed down between family members? 3. Of the three skills good singing requires: pitch accuracy, keeping time, and note memory, which do most people struggle with? 4. Can you train your brain to overcome imitative deficit? 5. Name one technique you can use to improve the quality and/or tone of your voice. 6. What is “vocal twang?” 7. What is vibrato? 8. What skill do our brains have that allows us to enjoy good music even if we aren’t good singers ourselves? 9. If you were not born with a good voice, can you develop one? 10. Since the size and length of our vocal folds are set for life, which aspects of your voice can be trained and developed? © 2018 IN TUNE PARTNERS, LLC TODAY’S MUSIC EDUCATION RESOURCE Name: STUDENT QUIZ THEATER THEMES Take this short quiz to test your knowledge about musicals about music. 1. Name four performances mentioned in the article. 2. What is special about a musical about music? 3. What is a “jukebox musical?” 4. Whose music is featured in the musical, We Will Rock You? 5. What decade is the music in Rock of Ages from? 6. What is the title of the musical created about the life and times of Carole King? 7. What happens in the story of The Band’s Visit? 8. -

Marketing Plan

ALLIED ARTISTS MUSIC GROUP An Allied Artists Int'l Company MARKETING & PROMOTION MARKETING PLAN: ROCKY KRAMER "FIRESTORM" Global Release Germany & Rest of Europe Digital: 3/5/2019 / Street 3/5/2019 North America & Rest of World Digital: 3/19/2019 / Street 3/19/2019 MASTER PROJECT AND MARKETING STRATEGY 1. PROJECT GOAL(S): The main goal is to establish "Firestorm" as an international release and to likewise establish Rocky Kramer's reputation in the USA and throughout the World as a force to be reckoned with in multiple genres, e.g. Heavy Metal, Rock 'n' Roll, Progressive Rock & Neo-Classical Metal, in particular. Servicing and exposure to this product should be geared toward social media, all major radio stations, college radio, university campuses, American and International music cable networks, big box retailers, etc. A Germany based advance release strategy is being employed to establish the Rocky Kramer name and bona fides within the "metal" market, prior to full international release.1 2. OBJECTIVES: Allied Artists Music Group ("AAMG"), in association with Rocky Kramer, will collaborate in an innovative and versatile marketing campaign introducing Rocky and The Rocky Kramer Band (Rocky, Alejandro Mercado, Michael Dwyer & 1 Rocky will begin the European promotional campaign / tour on March 5, 2019 with public appearances, interviews & live performances in Germany, branching out to the rest of Europe, before returning to the U.S. to kick off the global release on March 19, 2019. ALLIED ARTISTS INTERNATIONAL, INC. ALLIED ARTISTS MUSIC GROUP 655 N. Central Ave 17th Floor Glendale California 91203 455 Park Ave 9th Floor New York New York 10022 L.A. -

Q2 2020 Trend Highlights

2020 Mid-Year THETHE STSTAATETE OFOF THETHE HOTHOT 100 100 TOPTOP 1010 SELECT HIGHLIGHTS Compositional and Industry Trends for the Billboard Hot 100 Top 10 The State of the Hot 100 Top 10 takes an in-depth look at Q1 and Q2 2020's compositional and industry-related trends for the Billboard Hot 100 Top 10. What follows are a few select highlights from the report. SONGS..............................................................................................................................................................PAGE 2 PERFORMING ARTISTS.........................................................................................................................PAGE 3 SONGWRITERS...........................................................................................................................................PAGE 6 PRODUCERS.................................................................................................................................................PAGE 10 RECORD LABELS.......................................................................................................................................PAGE 13 #1 SPOTLIGHT..............................................................................................................................................PAGE 16 2019 VS. 2020 COMPOSITIONAL TRENDS.............................................................................PAGE 20 Data is for songs that charted in the Billboard Hot 100 Top 10 and excludes holiday songs. Data related to compositional characteristics -

Austrian Rap Music and Sonic Reproducibility by Edward

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ETD - Electronic Theses & Dissertations The Poetic Loop: Austrian Rap Music and Sonic Reproducibility By Edward C. Dawson Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in German May 11, 2018 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Christoph M. Zeller, Ph.D. Lutz P. Koepnick, Ph.D. Philip J. McFarland, Ph.D. Joy H. Calico, Ph.D. Copyright © 2018 by Edward Clark Dawson All Rights Reserved ii For Abby, who has loved “the old boom bap” from birth, and whose favorite song is discussed on pages 109-121, and For Margaret, who will surely express a similar appreciation once she learns to speak. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work would not have been possible without an Ernst Mach Fellowship from the Austrian Exchange Service (OeAD), which allowed me to spend the 2015-16 year conducting research in Vienna. I would like to thank Annagret Pelz for her support, as well as all the participants in the 2015-2016 Franz Werfel Seminar, whose feedback and suggestions were invaluable, especially Caroline Kita and organizers Michael Rohrwasser and Constanze Fliedl. During my time in Vienna, I had the opportunity to learn about Austrian rap from a number of artists and practitioners, and would like to thank Flip and Huckey of Texta, Millionen Keys, and DJ Taekwondo. A special thank you to Tibor Valyi-Nagy for attending shows with me and drawing my attention to connections I otherwise would have missed. -

Inhalt - Teil 1

Inhalt - Teil 1 Vorwort (Gottfried Heinzmann) 8 Herzlichen Dank (Katja Heimann und Nicole Hauser) , 10 Praktische Tipps - Wie halte ich am besten die Liedandacht? 11 Die Songandachten 13 Ich+Ich: Universum 14 Freiheit; Nähe; Geborgenheit Udo Lindenberg feat. Jan Delay: Ganz anders 16 Identität Curse: Freiheit 18 Freiheit; Zuhause L Train: Marry me 20 Mut; Entscheidungen; Beziehung zu Jesus Jessie J: Price tag 22 Liebe Gottes; Selbstwert Laith Al-Deen: Sicher sein 24 Sicherheit; Vertrauen; Zukunft Kings of Leon: Use somebody 26 Vorbilder; Anerkennung Ich+Ich: Pflaster 28 Wunde Punkte; Heilung Andreas Bourani: Nur in meinem Kopf 30 Positives Denken; Negatives Denken; Neustart Unheilig: Geboren, um zu leben 32 Leben; Veränderung Lenny Kravitz: If you want it 34 Leben; Freiheit Bushido: Wärst du immer noch hier? 36 Liebe; Treue; Anerkennung 1 http://d-nb.info/1018131043 Curse: Und was jetzt? 38 Beziehung; Trennung; Vergebung; Liebe Philipp Poisel: Froh, dabei zu sein 40 Tod; Sterben; Hoffnung Blumentopf: Mehr 42 Unzufriedenheit; Veränderung Greenday: Boulevard of broken dreams 44 Lebensweg; Sinn des Lebens Laith Al-Deen: Alles an dir 46 Freiheit; Selbstbestimmung; Fremdbestimmung Jupiter Jones: Still 48 Vermissen; Zweifel Clueso: Zu schnell vorbei 50 Zeit; Veränderung Tim Bendzko: Nur noch kurz die Welt retten 52 Jesus; Nachfolge Revolverheld: Spinner 54 Berufung; Begleitung; Beziehung Die Toten Hosen: Ich bin die Sehnsucht in dir 56 Angst; Rettung; Sehnsucht Die Ärzte: Lasse reden 58 Ansehen; Lästern; Selbstwert Revolverheld: Halt dich an