Infectious Mononucleosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Use of Cell Culture in Virology for Developing Countries in the South-East Asia Region © World Health Organization 2017

USE OF CELL C USE OF CELL U LT U RE IN VIROLOGY FOR DE RE IN VIROLOGY V ELOPING C O U NTRIES IN THE NTRIES IN S O U TH- E AST USE OF CELL CULTURE A SIA IN VIROLOGY FOR R EGION ISBN: 978-92-9022-600-0 DEVELOPING COUNTRIES IN THE SOUTH-EAST ASIA REGION World Health House Indraprastha Estate, Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi-110002, India Website: www.searo.who.int USE OF CELL CULTURE IN VIROLOGY FOR DEVELOPING COUNTRIES IN THE SOUTH-EAST ASIA REGION © World Health Organization 2017 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition.” Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. -

Mononucleosis (Epstein - Barr Virus Infection , Mono)

Division of Disease Control What Do I Need To Know? Mononucleosis (Epstein - Barr Virus Infection , Mono) What is infectious mononucleosis? Infectious mononucleosis, also known as mono, is a viral disease that affects certain blood cells. It is caused by the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which is a member of the herpes virus family. Most cases occur sporadically and outbreaks are rare. Who is at risk for mono? While most people are exposed to EBV sometime in their lives, very few develop the symptoms of infectious mononucleosis. Infections in the United States are most common in group settings of adolescents, such as in educational institutions. Young children usually have only mild or no symptoms. What are the symptoms of mono? Fever Sore throat Severe fatigue Swollen lymph nodes Enlarged liver and spleen Occasional rash in those treated with ampicillin, amoxicillin or other penicillins How soon do symptoms appear? Symptoms appear from 30 to 50 days after infection. How is mono spread? The virus is spread by close person-to-person contact via saliva (on hands or toys or by kissing). In rare instances, the virus has been transmitted by blood transfusion or following organ transplant. When and for how long is a person able to spread the disease? The virus is shed in the throat during the illness and for up to a year after infection. After the initial infection, the virus tends to become dormant for a prolonged period and can later reactivate and be shed from the throat again. How is a person diagnosed? Laboratory tests are available. A health care professional should be consulted. -

Pdfs/ Ommended That Initial Cultures Focus on Common Pathogens, Pscmanual/9Pscssicurrent.Pdf)

Clinical Infectious Diseases IDSA GUIDELINE A Guide to Utilization of the Microbiology Laboratory for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases: 2018 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society for Microbiologya J. Michael Miller,1 Matthew J. Binnicker,2 Sheldon Campbell,3 Karen C. Carroll,4 Kimberle C. Chapin,5 Peter H. Gilligan,6 Mark D. Gonzalez,7 Robert C. Jerris,7 Sue C. Kehl,8 Robin Patel,2 Bobbi S. Pritt,2 Sandra S. Richter,9 Barbara Robinson-Dunn,10 Joseph D. Schwartzman,11 James W. Snyder,12 Sam Telford III,13 Elitza S. Theel,2 Richard B. Thomson Jr,14 Melvin P. Weinstein,15 and Joseph D. Yao2 1Microbiology Technical Services, LLC, Dunwoody, Georgia; 2Division of Clinical Microbiology, Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota; 3Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut; 4Department of Pathology, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, Maryland; 5Department of Pathology, Rhode Island Hospital, Providence; 6Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; 7Department of Pathology, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Georgia; 8Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee; 9Department of Laboratory Medicine, Cleveland Clinic, Ohio; 10Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Beaumont Health, Royal Oak, Michigan; 11Dartmouth- Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, New Hampshire; 12Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Louisville, Kentucky; 13Department of Infectious Disease and Global Health, Tufts University, North Grafton, Massachusetts; 14Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, NorthShore University HealthSystem, Evanston, Illinois; and 15Departments of Medicine and Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, New Jersey Contents Introduction and Executive Summary I. -

Rabies Surveillance, South Dakota, 2014 Rabies Is an Enzootic, Nearly

VOLUME 27 NUMBER 2 MARCH 2015 CONTENTS: Colorectal cancer, 2012. page 6 | HIV/AIDS surveillance 2014 . page 8 | Kindergarten vaccination rates and exemptions. page 10 | Pediatric Upper Respiratory Guidelines. page 21 | Selected South Dakota mor- bidity report, January—February, 2015 . page 30 Rabies Surveillance, South Dakota, 2014 Animal rabies, South Dakota 2014 Rabies is an enzootic, nearly-always fatal, viral disease and a serious public health concern in South Dakota. In 2014, 588 ani- mals were tested for rabies with 21 testing positive, 3.6%, a - 25% decrease from the previous year. The 21 rabid animals in- cluded 3 domestic animals (1 bovine, 1 cat and 1 goat), and 18 wild animals (12 skunks and 6 bats). 2014 had the fewest rabid animals reported since 1960. No human rabies was reported. South Dakota’s last human rabies case was in 1970 when a 3 year old Brule County child was bitten by a rabid skunk. Four years earlier, in 1966, a 10 year old Hamlin County boy also died from skunk rabies. During 2014, 567 animals tested negative for rabies, including 161 bats, 154 cats, 90 dogs, 80 cattle, 24 raccoons, 13 skunks, 10 horses, 9 deer, 4 mice, 3 each coyotes, goats and opossums, 2 each woodchucks, muskrats, rabbits and squirrels, and 1 each llama, rat, sheep, shrew and weasel. During 2014 animals were submitted for testing from 55 of South Dakota’s 66 counties, and 17 counties reported rabid animals. Over the past decade, 2005-2014, rabid animals were reported from 61 of the state’s counties, with every county, except Ziebach, submitting animals for testing. -

Infectious Mononucleosis Presenting As Raynaud's Phenomenon

Infectious Mononucleosis Presenting as Raynaud’s Phenomenon Howard K. Rabinowitz, MD Philadelphia, Pennsylvania nfectious mononucleosis is a common illness caused by On initial examination, the patient’s fingers were noted the Epstein-Barr virus. While it is frequently seen in to be cyanotic, as were his ears and nose. After warming up youngI adults with its typical presentation (ie, pharyngitis, to the inside office temperature, however, his cyanosis dis fever, lymphadenopathy,' lymphocytosis with an elevated appeared, and he developed increasing erythema, espe percentage of atypical lymphocytes, and serologic evi cially in his hands and ears, with reddish streaks over his dence of heterophile antibodies), the clinical manifesta face. The remainder of his physical examination was tions of infectious mononucleosis are myriad and include within normal limits. After all of his symptoms resolved in jaundice, myocarditis, splenic rupture, autoimmune hemo the office, the patient’s hand was immersed in ice water, lytic anemia, and neurologic complications such as enceph whereupon he exhibited the classic changes of Raynaud’s alitis, optic neuritis, Guillain-Barre syndrome, and Bell’s phenomenon: pallor, cyanosis, and rubor. Initial laboratory palsy.1-2 This article describes a patient with infectious tests included a hemoglobin of 135 g/L (13.5 g/dL), mononucleosis who presented with Raynaud’s phenome hematocrit of 0.38 (38%), and white blood cell count of 9.3 non, a previously unreported association, and discusses the X 109/L (9300 mm-3), with 0.48 (48%) lymphocytes and implication of this case report. 0.12 (12%) atypical lymphocytes. His erythrocyte sedi mentation rate was markedly elevated at 72 mm/h. -

The Development of New Therapies for Human Herpesvirus 6

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect The development of new therapies for human herpesvirus 6 2 1 Mark N Prichard and Richard J Whitley Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) infections are typically mild and data from viruses are generally analyzed together and in rare cases can result in encephalitis. A common theme reported simply as HHV-6 infections. Here, we will among all the herpesviruses, however, is the reactivation upon specify the specific virus where possible and will simply immune suppression. HHV-6 commonly reactivates in use the HHV-6 designation where it is not. Primary transplant recipients. No therapies are approved currently for infection with HHV-6B has been shown to be the cause the treatment of these infections, although small studies and of exanthem subitum (roseola) in infants [4], and can also individual case reports have reported intermittent success with result in an infectious mononucleosis-like illness in adults drugs such as cidofovir, ganciclovir, and foscarnet. In addition [5]. Infections caused by HHV-6A and HHV-7 have not to the current experimental therapies, many other compounds been well characterized and are typically reported in the have been reported to inhibit HHV-6 in cell culture with varying transplant setting [6,7]. Serologic studies indicated that degrees of efficacy. Recent advances in the development of most people become infected with HHV-6 by the age of new small molecule inhibitors of HHV-6 will be reviewed with two, most likely through saliva transmission [8]. The regard to their efficacy and spectrum of antiviral activity. The receptors for HHV-6A and HHV-6B have been identified potential for new therapies for HHV-6 infections will also be as CD46 and CD134, respectively [9,10]. -

Mononucleosis

Infectious Mononucleosis You are being provided with this fact sheet: because you or your child may have been exposed to infectious mononucleosis. If you believe your child has developed infectious mononucleosis, contact your health care provider. Notify your child care provider or preschool if a diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis is made. for informational purposes only. What is infectious mononucleosis? Infectious mononucleosis, sometimes called “mono,” is a viral illness caused by the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). Most people become infected with this virus at some time in their lives. What are the symptoms of infectious mononucleosis? Symptoms of illness appear 4 to 7 weeks after an individual is exposed to the virus. Young children often show mild or no symptoms of illness. Older children and adults who have mononucleosis may have fever*, sore throat, swollen tonsils, fatigue, headache, rash and swollen glands. These symptoms may last from one to several weeks. How is infectious mononucleosis spread? Infectious mononucleosis is most commonly spread from person to person through contact with the saliva of an infected person. This may occur with kissing on the mouth or sharing items like food utensils, drinking cups, or mouthed toys with an infected individual. Who may become ill with infectious mononucleosis? Most adults have been exposed to the Epstein-Barr virus by the age of 18 and are therefore immune. Once a person has been infected, the virus stays dormant in the cells of the throat and in the blood for the rest of the person’s life. Periodically, the virus can reactivate and be found in the saliva of persons who have no symptoms. -

CDC/NHSN Surveillance Definitions for Specific Types of Infections

Surveillance Definitions CDC/NHSN Surveillance Definitions for Specific Types of Infections INTRODUCTION This chapter contains the CDC/NHSN surveillance definitions and criteria for all specific types of infections. Comments and reporting instructions that follow the site-specific criteria provide further explanation and are integral to the correct application of the criteria. This chapter also provides further required criteria for the specific infection types that constitute organ/space surgical site infections (SSI) (e.g., mediastinitis [MED] that may follow a coronary artery bypass graft, intra-abdominal abscess [IAB] after colon surgery). Additionally, it is necessary to refer to the criteria in this chapter when determining whether a positive blood culture represents a primary bloodstream infection (BSI) or is secondary to a different type of HAI (see Appendix 1 Secondary Bloodstream Infection (BSI) Guide). A BSI that is identified as secondary to another site of HAI must meet one of the criteria of HAI detailed in this chapter. Secondary BSIs are not reported as separate events in NHSN, nor can they be associated with the use of a central line. Also included in this chapter are the criteria for Ventilator-Associated Events (VAEs). It should be noted that Ventilator-Associated Condition (VAC), the first definition within the VAE surveillance definition algorithm and the foundation for the other definitions within the algorithm (IVAC, Possible VAP, Probable VAP) may or may not be infection-related. CDC/NHSN SURVEILLANCE DEFINITIONS OF HEALTHCARE–ASSOCIATED INFECTION Present on Admission (POA) Infections To standardize the classification of an infection as present on admission (POA) or a healthcare- associated infection (HAI), the following objective surveillance criteria have been adopted by NHSN. -

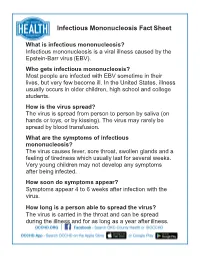

Infectious Mononucleosis Fact Sheet

Infectious Mononucleosis Fact Sheet What is infectious mononucleosis? Infectious mononucleosis is a viral illness caused by the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). Who gets infectious mononucleosis? Most people are infected with EBV sometime in their lives, but very few become ill. In the United States, illness usually occurs in older children, high school and college students. How is the virus spread? The virus is spread from person to person by saliva (on hands or toys, or by kissing). The virus may rarely be spread by blood transfusion. What are the symptoms of infectious mononucleosis? The virus causes fever, sore throat, swollen glands and a feeling of tiredness which usually last for several weeks. Very young children may not develop any symptoms after being infected. How soon do symptoms appear? Symptoms appear 4 to 6 weeks after infection with the virus. How long is a person able to spread the virus? The virus is carried in the throat and can be spread during the illness and for as long as a year after illness. Infectious Mononucleosis Fact Sheet What is the treatment for infectious mononucleosis? No treatment other than rest is needed for most cases; persons with very hoarse (swollen) throats should see their doctor. Can a person get infectious mononucleosis again? People who get the illness rarely get it again. What can a person do to stop the spread of EBV? Avoid contact with the body fluids (commonly saliva) of someone who is infected with the virus. At present, there is no vaccine available to prevent mono. For further information, contact the Oklahoma City-County Health Department (405) 425-4437 revised 04/2013 . -

Infectious Mononucleosis

University of Nebraska Medical Center DigitalCommons@UNMC MD Theses Special Collections 5-1-1942 Infectious mononucleosis Richard R. Stappenbeck University of Nebraska Medical Center This manuscript is historical in nature and may not reflect current medical research and practice. Search PubMed for current research. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/mdtheses Part of the Medical Education Commons Recommended Citation Stappenbeck, Richard R., "Infectious mononucleosis" (1942). MD Theses. 955. https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/mdtheses/955 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at DigitalCommons@UNMC. It has been accepted for inclusion in MD Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNMC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. C) INFECTIOUS MONONUCLEOSIS Richard,. Stap~nieck * Senior theeie presented to the College of Medicine, University ot Nebraska Omaha 1942 TABLI· or OOBTElffS (Page) Introduction 1 I. History l II. Distribution 7 III. Clinical Picture 9 IV. Laboratory Findings 27 v. Diagnoeia ,; VI. Patholoa "° VII. Ditterential Diagnosis 42 VIII. Etiology Jt8 IX. 'l'heraw 52 x. Oonclusione !54 481338 1 INFEOTIOUS MONONUCLEOSIS (Glandular Fever) Infectious mononucleoeis may be described as an acute infectious disease characterized by fever, enlargement of the lymphatic glands, and ehangee in the blood, especially lymphocytoeis.(l) Since the introduction of the eerologic diagnostic test of Paul and Bunnell in 19,2, there has been an awakened interest in infectious mononucleosis. Oases which were formerly entirely overlooked or only suspected could be confirmed as examples of infectious mononucleosis by this teat.(2) Bet-ween 1928 and 19,2 such men as Ohevallier of Paris, Glanzmann of Bern•, Lehndortt and Swartz of Vienna, and Nyfeldt of Copenhagen publiah•d aoae excellent monograms on infectious mono nucleosis.(') I. -

Blood Cultures - Aerobic & Anaerobic

Blood Cultures - Aerobic & Anaerobic Blood cultures are drawn into special bottles that contain a special medium that will support the growth and allow the detection of micro- organisms that prefer oxygen (aerobes) or that thrive in a reduced-oxygen environment (anaerobes). Multiple samples are usually collected. Routine standard of care indicates a minimum of Two Separate Sites or collected At Least 15 Minutes Apart. Multiple Collection/Multiple Site collection is done to aid in the detection of micro-organism s present in small numbers and/or may be released into the bloodstream intermittently. Samples must be incubated for several days before resulting to ensure that the sample is indeed negative before resulting out. Synergy Laboratories uses state of the art automated instrumentation that provides continuous monitoring. This allows for more rapid detection of samples that do contain bacteria or yeast. CONSIDER AEROBIC CONSIDER ANAEROBIC BLOOD CULTURES IN: BLOOD CULTURES IN: 1) New onset of fever, change in pattern of fever or unexplained clinical 1) Intra-abdominal infection instability. 2) Hemodynamic instability with or without fever if infection is a 2) Sepsis/septic shock from GI site possibility. 3) Necrotizing fasciitis or complicated 3) Possible endocarditis or graft infection. skin/soft tissue infection. 4) Unexplained hyperglycemia or 4) Severe oropharyngeal or dental hypotension. infection. 5) To assess cure of bacteremia. 5) Lung abscess or cavitary lesion. 6) Presence of a vascular catheter and 6) Massive blunt abdominal trauma. clinical instability. Body Fluid Specimens Selection Collect the specimen using strict aseptic technique. The patient should be fasting. If only one tube of fluid is available, the microbiology laboratory gets it first. -

Post-Infectious Fatigue

Review Article Post-Infectious Fatigue JMAJ 49(1): 27–33, 2006 Kazuhiro Kondo*1 Abstract Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) and Gulf War Syndrome are diseases of unknown etiology which are accom- panied by severe fatigue as a main complaint. Yet there may be some kind of “post-infectious fatigue syndrome” following any infection by a virus. Post-infectious fatigue, which is caused by many different viruses, includes chronic active Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection and it is thought that the onset of this disease is associated with latent EBV infection in a very unusual manner. As there may be an unusual latent infection with human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) which may be an etiology of CFS in the CFS patients, the study on latent infection is considered to be important for elucidating CFS and Gulf War Syndrome. Key words Infection, Fatigue, Chronic fatigue syndrome, Gulf War Syndrome, Epstein-Barr virus, Human herpesvirus 6 This paper examines knowledge currently Introduction available on the mechanism of fatigue and dis- cusses the relationship of infection with severe Fatigue is caused by many different factors, of post-infectious fatigue, particularly with the onset which infection is one of the very important of CFS. causes. Fatigue, which not only deteriorates work efficiency but also constitutes causes of various Mechanism of Fatigue diseases and death from overwork, poses a seri- ous health problem for people. In spite of such In general, “fatigue” is defined as decreased importance, however, the mechanisms of fatigue, physical functions attributable to prolonged by which fatigue is caused and felt, have been physical and/or mental stresses, while “tired- hardly known.