Infectious Mononucleosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mononucleosis (Epstein - Barr Virus Infection , Mono)

Division of Disease Control What Do I Need To Know? Mononucleosis (Epstein - Barr Virus Infection , Mono) What is infectious mononucleosis? Infectious mononucleosis, also known as mono, is a viral disease that affects certain blood cells. It is caused by the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which is a member of the herpes virus family. Most cases occur sporadically and outbreaks are rare. Who is at risk for mono? While most people are exposed to EBV sometime in their lives, very few develop the symptoms of infectious mononucleosis. Infections in the United States are most common in group settings of adolescents, such as in educational institutions. Young children usually have only mild or no symptoms. What are the symptoms of mono? Fever Sore throat Severe fatigue Swollen lymph nodes Enlarged liver and spleen Occasional rash in those treated with ampicillin, amoxicillin or other penicillins How soon do symptoms appear? Symptoms appear from 30 to 50 days after infection. How is mono spread? The virus is spread by close person-to-person contact via saliva (on hands or toys or by kissing). In rare instances, the virus has been transmitted by blood transfusion or following organ transplant. When and for how long is a person able to spread the disease? The virus is shed in the throat during the illness and for up to a year after infection. After the initial infection, the virus tends to become dormant for a prolonged period and can later reactivate and be shed from the throat again. How is a person diagnosed? Laboratory tests are available. A health care professional should be consulted. -

Rabies Surveillance, South Dakota, 2014 Rabies Is an Enzootic, Nearly

VOLUME 27 NUMBER 2 MARCH 2015 CONTENTS: Colorectal cancer, 2012. page 6 | HIV/AIDS surveillance 2014 . page 8 | Kindergarten vaccination rates and exemptions. page 10 | Pediatric Upper Respiratory Guidelines. page 21 | Selected South Dakota mor- bidity report, January—February, 2015 . page 30 Rabies Surveillance, South Dakota, 2014 Animal rabies, South Dakota 2014 Rabies is an enzootic, nearly-always fatal, viral disease and a serious public health concern in South Dakota. In 2014, 588 ani- mals were tested for rabies with 21 testing positive, 3.6%, a - 25% decrease from the previous year. The 21 rabid animals in- cluded 3 domestic animals (1 bovine, 1 cat and 1 goat), and 18 wild animals (12 skunks and 6 bats). 2014 had the fewest rabid animals reported since 1960. No human rabies was reported. South Dakota’s last human rabies case was in 1970 when a 3 year old Brule County child was bitten by a rabid skunk. Four years earlier, in 1966, a 10 year old Hamlin County boy also died from skunk rabies. During 2014, 567 animals tested negative for rabies, including 161 bats, 154 cats, 90 dogs, 80 cattle, 24 raccoons, 13 skunks, 10 horses, 9 deer, 4 mice, 3 each coyotes, goats and opossums, 2 each woodchucks, muskrats, rabbits and squirrels, and 1 each llama, rat, sheep, shrew and weasel. During 2014 animals were submitted for testing from 55 of South Dakota’s 66 counties, and 17 counties reported rabid animals. Over the past decade, 2005-2014, rabid animals were reported from 61 of the state’s counties, with every county, except Ziebach, submitting animals for testing. -

Infectious Mononucleosis Presenting As Raynaud's Phenomenon

Infectious Mononucleosis Presenting as Raynaud’s Phenomenon Howard K. Rabinowitz, MD Philadelphia, Pennsylvania nfectious mononucleosis is a common illness caused by On initial examination, the patient’s fingers were noted the Epstein-Barr virus. While it is frequently seen in to be cyanotic, as were his ears and nose. After warming up youngI adults with its typical presentation (ie, pharyngitis, to the inside office temperature, however, his cyanosis dis fever, lymphadenopathy,' lymphocytosis with an elevated appeared, and he developed increasing erythema, espe percentage of atypical lymphocytes, and serologic evi cially in his hands and ears, with reddish streaks over his dence of heterophile antibodies), the clinical manifesta face. The remainder of his physical examination was tions of infectious mononucleosis are myriad and include within normal limits. After all of his symptoms resolved in jaundice, myocarditis, splenic rupture, autoimmune hemo the office, the patient’s hand was immersed in ice water, lytic anemia, and neurologic complications such as enceph whereupon he exhibited the classic changes of Raynaud’s alitis, optic neuritis, Guillain-Barre syndrome, and Bell’s phenomenon: pallor, cyanosis, and rubor. Initial laboratory palsy.1-2 This article describes a patient with infectious tests included a hemoglobin of 135 g/L (13.5 g/dL), mononucleosis who presented with Raynaud’s phenome hematocrit of 0.38 (38%), and white blood cell count of 9.3 non, a previously unreported association, and discusses the X 109/L (9300 mm-3), with 0.48 (48%) lymphocytes and implication of this case report. 0.12 (12%) atypical lymphocytes. His erythrocyte sedi mentation rate was markedly elevated at 72 mm/h. -

The Development of New Therapies for Human Herpesvirus 6

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect The development of new therapies for human herpesvirus 6 2 1 Mark N Prichard and Richard J Whitley Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) infections are typically mild and data from viruses are generally analyzed together and in rare cases can result in encephalitis. A common theme reported simply as HHV-6 infections. Here, we will among all the herpesviruses, however, is the reactivation upon specify the specific virus where possible and will simply immune suppression. HHV-6 commonly reactivates in use the HHV-6 designation where it is not. Primary transplant recipients. No therapies are approved currently for infection with HHV-6B has been shown to be the cause the treatment of these infections, although small studies and of exanthem subitum (roseola) in infants [4], and can also individual case reports have reported intermittent success with result in an infectious mononucleosis-like illness in adults drugs such as cidofovir, ganciclovir, and foscarnet. In addition [5]. Infections caused by HHV-6A and HHV-7 have not to the current experimental therapies, many other compounds been well characterized and are typically reported in the have been reported to inhibit HHV-6 in cell culture with varying transplant setting [6,7]. Serologic studies indicated that degrees of efficacy. Recent advances in the development of most people become infected with HHV-6 by the age of new small molecule inhibitors of HHV-6 will be reviewed with two, most likely through saliva transmission [8]. The regard to their efficacy and spectrum of antiviral activity. The receptors for HHV-6A and HHV-6B have been identified potential for new therapies for HHV-6 infections will also be as CD46 and CD134, respectively [9,10]. -

Mononucleosis

Infectious Mononucleosis You are being provided with this fact sheet: because you or your child may have been exposed to infectious mononucleosis. If you believe your child has developed infectious mononucleosis, contact your health care provider. Notify your child care provider or preschool if a diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis is made. for informational purposes only. What is infectious mononucleosis? Infectious mononucleosis, sometimes called “mono,” is a viral illness caused by the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). Most people become infected with this virus at some time in their lives. What are the symptoms of infectious mononucleosis? Symptoms of illness appear 4 to 7 weeks after an individual is exposed to the virus. Young children often show mild or no symptoms of illness. Older children and adults who have mononucleosis may have fever*, sore throat, swollen tonsils, fatigue, headache, rash and swollen glands. These symptoms may last from one to several weeks. How is infectious mononucleosis spread? Infectious mononucleosis is most commonly spread from person to person through contact with the saliva of an infected person. This may occur with kissing on the mouth or sharing items like food utensils, drinking cups, or mouthed toys with an infected individual. Who may become ill with infectious mononucleosis? Most adults have been exposed to the Epstein-Barr virus by the age of 18 and are therefore immune. Once a person has been infected, the virus stays dormant in the cells of the throat and in the blood for the rest of the person’s life. Periodically, the virus can reactivate and be found in the saliva of persons who have no symptoms. -

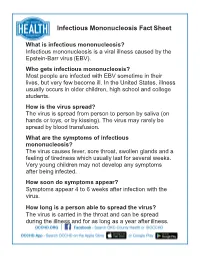

Infectious Mononucleosis Fact Sheet

Infectious Mononucleosis Fact Sheet What is infectious mononucleosis? Infectious mononucleosis is a viral illness caused by the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). Who gets infectious mononucleosis? Most people are infected with EBV sometime in their lives, but very few become ill. In the United States, illness usually occurs in older children, high school and college students. How is the virus spread? The virus is spread from person to person by saliva (on hands or toys, or by kissing). The virus may rarely be spread by blood transfusion. What are the symptoms of infectious mononucleosis? The virus causes fever, sore throat, swollen glands and a feeling of tiredness which usually last for several weeks. Very young children may not develop any symptoms after being infected. How soon do symptoms appear? Symptoms appear 4 to 6 weeks after infection with the virus. How long is a person able to spread the virus? The virus is carried in the throat and can be spread during the illness and for as long as a year after illness. Infectious Mononucleosis Fact Sheet What is the treatment for infectious mononucleosis? No treatment other than rest is needed for most cases; persons with very hoarse (swollen) throats should see their doctor. Can a person get infectious mononucleosis again? People who get the illness rarely get it again. What can a person do to stop the spread of EBV? Avoid contact with the body fluids (commonly saliva) of someone who is infected with the virus. At present, there is no vaccine available to prevent mono. For further information, contact the Oklahoma City-County Health Department (405) 425-4437 revised 04/2013 . -

Post-Infectious Fatigue

Review Article Post-Infectious Fatigue JMAJ 49(1): 27–33, 2006 Kazuhiro Kondo*1 Abstract Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) and Gulf War Syndrome are diseases of unknown etiology which are accom- panied by severe fatigue as a main complaint. Yet there may be some kind of “post-infectious fatigue syndrome” following any infection by a virus. Post-infectious fatigue, which is caused by many different viruses, includes chronic active Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection and it is thought that the onset of this disease is associated with latent EBV infection in a very unusual manner. As there may be an unusual latent infection with human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) which may be an etiology of CFS in the CFS patients, the study on latent infection is considered to be important for elucidating CFS and Gulf War Syndrome. Key words Infection, Fatigue, Chronic fatigue syndrome, Gulf War Syndrome, Epstein-Barr virus, Human herpesvirus 6 This paper examines knowledge currently Introduction available on the mechanism of fatigue and dis- cusses the relationship of infection with severe Fatigue is caused by many different factors, of post-infectious fatigue, particularly with the onset which infection is one of the very important of CFS. causes. Fatigue, which not only deteriorates work efficiency but also constitutes causes of various Mechanism of Fatigue diseases and death from overwork, poses a seri- ous health problem for people. In spite of such In general, “fatigue” is defined as decreased importance, however, the mechanisms of fatigue, physical functions attributable to prolonged by which fatigue is caused and felt, have been physical and/or mental stresses, while “tired- hardly known. -

Infectious Mononucleosis

THEME: Systemic viral infections Infectious mononucleosis BACKGROUND Infectious mononucleosis is caused by the ubiquitous Epstein-Barr virus. It is a common condition usually affecting adolescents and young adults. Most cases are mild to moderate in severity with full recovery taking place over several weeks. More severe cases Patrick G P Charles and unusual complications occasionally occur. OBJECTIVE After presenting a case of severe infectious mononucleosis, the spectrum of disease is given. Diagnosis and complications are reviewed as well as management including the possible role for antiviral medications or corticosteroid therapy. DISCUSSION The majority of cases of infectious mononucleosis are self limiting and require only supportive care. More severe cases, although unusual, may require admission to hospital and even to an intensive care unit. Corticosteroid therapy may be indicated for severe airway obstruction or other severe complications, but should be avoided unless the benefits outweigh potential risks. Antiviral therapy has no proven benefit. Patrick G P Charles, Case history MBBS, is a registrar, Victorian Infectious A 21 year old exchange student was admitted with a week long history of sore throat, fever, lethargy, anorexia Disease Reference and headache. His intake of food and fluids had been markedly reduced. He sought medical advice when he Laboratory, North noticed he had become jaundiced. He had no risk factors for, nor contact with, viral hepatitis. Melbourne, Victoria. Initial examination revealed he was volume depleted and clearly icteric. He was febrile at 38.6ºC and had generalised lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly and markedly enlarged tonsils that were mildly inflamed. There was no tonsillar exudate or palatal petechiae. -

Igm Serum Antibodies to Epstein-Barr Virus Are Uniquely Present in a Subset of Patients with the Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

in vivo 18: 101-106 (2004) IgM Serum Antibodies to Epstein-Barr Virus are Uniquely Present in a Subset of Patients with the Chronic Fatigue Syndrome A. MARTIN LERNER1, SAFEDIN H. BEQAJ2, ROBERT G. DEETER3 and JAMES T. FITZGERALD4 1Departments of 1Medicine and 2Pathology, William Beaumont Hospital and Wayne State University School of Medicine, Royal Oak, Michigan; 3Glaxo-Wellcome Co. Research Triangle Park, North Carolina; 4Department of Medical Education, University of Michigan School of Medicine, Ann Arbor, Michigan, U.S.A. Abstract. Background: A unique subset of patients with of 16 CFS patients with unique IgM serum antibodies to chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) and IgM serum antibodies to human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) non-structural gene cytomegalovirus (HCMV) non-structural gene products p52 and products of the virus tegument, p52 and CM2 (UL44 and CM2 (UL 44 and UL 57) has been described. Patients and UL57). The HCMV IgM p52 and CM2 serum antibodies Methods: Fifty-eight CFS patients and 68 non-CFS matched were not present in 77 various control patients (p<0.05) (6). controls were studied. Serum antibodies to EBV viral capsid A subset of CFS may be a prolonged infectious antigen (VCA) IgM and EBV Early Antigen, diffuse (EA, D) mononucleosis-like syndrome caused by HCMV(7-9). as well HVCMV(V), IgM and IgG; VP (sucrose, density The EBV IgM serum antibody to viral capsid antigen purified V); p52 and CM2 IgM serum antibodies were assayed. (VCA) tested by ELISA methods is diagnostic for EBV Results: Mean age of CFS patients was 44 years (75% women). infectious mononucleosis (10-12). -

Poliomyelitis

Poliomyelitis Authors: Doctors David L. Heymann1 and R. Bruce Aylward Creation date: August 2004 Scientific Editor: Professor Hermann Feldmeier 1Polio Eradication Initiative WHO, Geneva 1211, Switzerland. [email protected] Abstract Key-words Disease name/ synonyms Definition/diagnostic criteria Differential Diagnosis Etiology Clinical description Diagnostic methods Epidemiology Management/treatment Unresolved questions References Abstract Poliomyelitis is a viral infection caused by any of three serotypes of human poliovirus and is most often recognized by the acute onset of flaccid paralysis. It affects primarily children under the age of 5 years. Transmission is primarily person-to-person spread, principally through the fecal-oral route. Usually the infection is limited to the gastrointestinal tract and nasopharynx, and is often asymptomatic. The central nervous system, primarily the spinal cord, may be affected, leading to rapidly progressive paralysis. Motor neurons are primarily affected. Encephalitis may also occur. The virus replicates in the nervous system, and may cause significant neuronal loss, most notably in the spinal cord. Poliomyelitis must be distinguished from other paralytic conditions by isolation of virus from stool. Prevention is the only cure for paralytic poliomyelitis. Both inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) and oral polio vaccine (OPV) are commercially available. Progress in poliomyelitis eradication since its beginning in 1988 has been remarkable. In 1988, 125 countries were endemic for polio and an estimated 1,000 children were being paralyzed each day by wild poliovirus. By the end of 2003, six polio-endemic countries remained (Afghanistan, Egypt, India, Niger, Nigeria, Pakistan), and less than 3 children per day were being paralyzed by the poliovirus. Interruption of human transmission of wild poliovirus worldwide is now targeted for the end of 2004. -

Requalification of Donors Previously Deferred for a History of Viral Hepatitis Th After the 11 Birthday

Requalification of Donors Previously Deferred for a History of Viral Hepatitis th after the 11 Birthday Guidance for Industry This guidance is for immediate implementation. FDA is issuing this guidance for immediate implementation in accordance with 21 CFR 10.115(g)(4)(i). Submit one set of either electronic or written comments on this guidance at any time. Submit electronic comments to http://www.regulations.gov. Submit written comments to the Dockets Management Staff (HFA-305), Food and Drug Administration, 5630 Fishers Lane, Rm. 1061, Rockville, MD 20852. You should identify all comments with docket number FDA-2017-D-5152. Additional copies of this guidance are available from the Office of Communication, Outreach and Development (OCOD), 10903 New Hampshire Ave., Bldg. 71, Rm. 3128, Silver Spring, MD 20993-0002, or by calling 1-800-835-4709 or 240-402-8010, or email [email protected], or from the Internet at http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guida nces/default.htm. For questions on the content of this guidance, contact OCOD at the phone numbers or email address listed above. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research September 2017 Contains Nonbinding Recommendations Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 1 II. BACKGROUND .............................................................................................................. -

Vaccine Adverse Events in the New Millennium: Is There Reason for Concern? B.J

Round Table Vaccine adverse events in the new millennium: is there reason for concern? B.J. Ward1 As more and more infectious agents become targets for immunization programmes, the spectrum of adverse events linked to vaccines has been widening. Although some of these links are tenuous, relatively little is known about the immunopathogenesis of even the best characterized vaccine-associated adverse events (VAAEs). The range of possible use of active immunization is rapidly expanding to include vaccines against infectious diseases that require cellular responses to provide protection (e.g. tuberculosis, herpes viral infections), therapeutic vaccines for chronic infections (e.g. human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, viral hepatitis B and C), and vaccines against non-infectious conditions (e.g. cancer, autoimmune diseases). Less virulent pathogens (e.g. varicella, rotavirus in the developed world) are also beginning to be targeted, and vaccine use is being justified in terms of societal and parental ``costs'' rather than in straightforward morbidity and mortality costs. In the developed world the paediatric immunization schedule is becoming crowded, with pressure to administer increasing numbers of antigens simultaneously in ever simpler forms (e.g. subcomponent, peptide, and DNA vaccines). This trend, while attractive in many ways, brings hypothetical risks (e.g. genetic restriction, narrowed shield of protection, and loss of randomness), which will need to be evaluated and monitored. The available epidemiological and laboratory tools to address the issues outlined above are somewhat limited. As immunological and genetic tools improve in the years ahead, it is likely that we shall be able to explain the immunopathogenesis of many VAAEs and perhaps even anticipate and avoid some of them.