A Critical Review of the Mediterranean Sea Turtle Rescue Network: a Web Looking for a Weaver

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reef Building Mediterranean Vermetid Gastropods: Disentangling the Dendropoma Petraeum Species Complex J

Research Article Mediterranean Marine Science Indexed in WoS (Web of Science, ISI Thomson) and SCOPUS The journal is available on line at http://www.medit-mar-sc.net DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/mms.1333 Zoobank: http://zoobank.org/25FF6F44-EC43-4386-A149-621BA494DBB2 Reef building Mediterranean vermetid gastropods: disentangling the Dendropoma petraeum species complex J. TEMPLADO1, A. RICHTER2 and M. CALVO1 1 Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (CSIC), José Gutiérrez Abascal 2, 28006 Madrid, Spain 2 Oviedo University, Faculty of Biology, Dep. Biology of Organisms and Systems (Zoology), Catedrático Rodrigo Uría s/n, 33071 Oviedo, Spain Corresponding author: [email protected] Handling Editor: Marco Oliverio Received: 21 April 2014; Accepted: 3 July 2015; Published on line: 20 January 2016 Abstract A previous molecular study has revealed that the Mediterranean reef-building vermetid gastropod Dendropoma petraeum comprises a complex of at least four cryptic species with non-overlapping ranges. Once specific genetic differences were de- tected, ‘a posteriori’ searching for phenotypic characters has been undertaken to differentiate cryptic species and to formally describe and name them. The name D. petraeum (Monterosato, 1884) should be restricted to the species of this complex dis- tributed around the central Mediterranean (type locality in Sicily). In the present work this taxon is redescribed under the oldest valid name D. cristatum (Biondi, 1857), and a new species belonging to this complex is described, distributed in the western Mediterranean. These descriptions are based on a comparative study focusing on the protoconch, teleoconch, and external and internal anatomy. Morphologically, the two species can be only distinguished on the basis of non-easily visible anatomical features, and by differences in protoconch size and sculpture. -

Marine Geophysical Research

Marine Geophysical Research Seabed mapping in the Pelagie Islands Marine Protected Area (Sicily Channel, southern Mediterranean) using Remote Sensing Object Based Image Analysis (RSOBIA) --Manuscript Draft-- Manuscript Number: MARI-D-18-00014R2 Full Title: Seabed mapping in the Pelagie Islands Marine Protected Area (Sicily Channel, southern Mediterranean) using Remote Sensing Object Based Image Analysis (RSOBIA) Article Type: Original Research Keywords: Multibeam bathymetry; backscatter; benthoscapes; seabed classification; ground- truth data; Posidonia oceanica; coralligenous habitat. Corresponding Author: Sara Innangi Istituto per l'ambiente marino costiero Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche ITALY Corresponding Author Secondary Information: Corresponding Author's Institution: Istituto per l'ambiente marino costiero Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche Corresponding Author's Secondary Institution: First Author: Sara Innangi First Author Secondary Information: Order of Authors: Sara Innangi Renato Tonielli Claudia Romagnoli Francesca Budillon Gabriella Di Martino Michele Innangi Roberta La Terza Tim Le Bas Claudio Lo Iacono Order of Authors Secondary Information: Funding Information: Abstract: AcceptedIn this paper we present the seabed maps of the shallow-water areas of Lampedusa and Linosa, belonging to the Pelagie Islands Marine Protected Area. Two surveys were carried out (“Lampedusa2015” and “Linosa2016”) to collect bathymetric and acoustic backscatter data through the use of a Reson SeaBat 7125 high-resolution multibeam system. Ground-truth -

Marine Turtles

UNEP/MED IG.24/22 Page 372 Decision IG.24/7 Strategies and Action Plans under the Protocol concerning Specially Protected Areas and Biological Diversity in the Mediterranean, including the SAP BIO, the Strategy on Monk Seal, and the Action Plans concerning Marine Turtles, Cartilaginous Fishes and Marine Vegetation; Classification of Benthic Marine Habitat Types for the Mediterranean Region, and Reference List of Marine and Coastal Habitat Types in the Mediterranean The Contracting Parties to the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment and the Coastal Region of the Mediterranean and its Protocols at their 21st Meeting, Recalling the outcome document of the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, entitled “The future we want”, endorsed by the General Assembly in its resolution 66/288 of 27 July 2012, in particular those paragraphs relevant to biodiversity, Recalling also General Assembly resolution 70/1 of 25 September 2015, entitled “Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”, and acknowledging the importance of conservation, the sustainable use and management of biodiversity in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, Recalling further the United Nations Environment Assembly resolutions UNEP/EA.4/Res.10 of 15 March 2019, entitled “Innovation on biodiversity and land degradation”, Bearing in mind the international community’s commitment expressed in the Ministerial Declaration of the United Nations Environment Assembly at its fourth session to implement sustainable ecosystems -

DXCC Entity Prefix Confirm. Needed Grid Square.Rev: 7/30/21 Cont. Sov

confirm. DXCC Entity Prefix Grid Square.rev: 7/30/21 Cont. needed Sov. Mil. Order of 1A0 1 JM75 EU Malta Monaco 3A 1 JN33 EU Agalega & St.Brandon 3B6,7 1 LH89 AF Mauritius 3B8 1 LG89 AF Rodriguez Is. 3B9 1 MH10 AF Equatorial Guinea 3C 1 JJ41, 51 AF Annobon Is. 3C0 1 JI28 AF Fiji 3D2/f 3 RH81-83, 90-93, AH01-03 OC Conway Reef 3D2/c 1 RG78 OC Rotuma Is. 3D2/r 1 RH87 OC Swaziland 3DA 2 KG52-54, 62-63 AF 3DA after eSwatini 2 KG52-54, 62-63 AF 18Apr2018 Tunisia 3V 2 JM33-34, 40-47, 50-57 AF OJ28-29, 39, OK20-21, 27-38, 40-46, Vietnam 3W, XV 4 AS OL00-01, 10-12, 20 IJ39, 48-49, 57-59, IK20-21, 30-32, 40-42, Guinea 3X 2 AF 50-52 Bouvet 3Y 1 JD15 AF Peter 1 Is. 3Y 1 EC41 AN LM 28-29, 38-39, 48-49, LN 20-21, 30-31. Azerbaijan 4J, 4K 3 AS 40-41, 50 Georgia 4L 3 LN 01-03, 11-13, 21-22, 31-32 AS Montenegro 4O after 28Jun2006 1 JN 91-93, KN 02-03 EU Sri Lanka 4P-4S 2 MJ 96-99, NJ 06-09 AS ITU HQ 4U_ITU (Geneva) 1 JN 36 EU 4U_UN United Nations HQ 1 FN 30 NA (New York) Timor-Leste 4W 1 PI 20-21, 30-31 OC Israel 4X, 4Z 3 KL 79, KM 70-73 AS JL 45-49, 53-59, 63-69, 72-79, 83-89, 91-99, JM 40, 50-52, 60-62, 70-72, 80-81, 90, KL Libya 5A 2 AF 00-09, 10-19, 20-29, KM 00-02, 10-12, 20- 21 Cyprus 5B 2 KM 64-65, 74-75 AS KH 78-89, 98-99, KI 43-45, 51-58, 60-67, Tanzania 5H-5I 3 AF 70-78, 80-87, 90-95 JJ 16-19, 24-29, 34-39, 44-49, 56-59, 68-69, Nigeria 5N-5O 3 JK 10-11, 20-23, 30-33, 40-43, 50-53, 60- AF 63, 71-72 LG 15-19, 24-29, 34-39, 47-49, LH 12, 20- Madagascar 5R-5S 2 AF 24, 30-36, 40-48, 53-56 Mauritania 5T 2 IK 16-19, 26-29, 34-39, 45-49, 55-59, 65-69, -

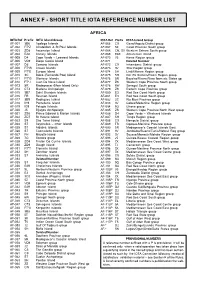

Short Title Iota Reference Number List

RSGB IOTA DIRECTORY ANNEX F - SHORT TITLE IOTA REFERENCE NUMBER LIST AFRICA IOTA Ref Prefix IOTA Island Group IOTA Ref Prefix IOTA Island Group AF-001 3B6 Agalega Islands AF-066 C9 Gaza/Maputo District group AF-002 FT*Z Amsterdam & St Paul Islands AF-067 5Z Coast Province South group AF-003 ZD8 Ascension Island AF-068 CN, S0 Western Sahara South group AF-004 EA8 Canary Islands AF-069 EA9 Alhucemas Island AF-005 D4 Cape Verde – Leeward Islands AF-070 V5 Karas Region group AF-006 VQ9 Diego Garcia Island AF-071 Deleted Number AF-007 D6 Comoro Islands AF-072 C9 Inhambane District group AF-008 FT*W Crozet Islands AF-073 3V Sfax Region group AF-009 FT*E Europa Island AF-074 5H Lindi/Mtwara Region group AF-010 3C Bioco (Fernando Poo) Island AF-075 5H Dar Es Salaam/Pwani Region group AF-011 FT*G Glorioso Islands AF-076 5N Bayelsa/Rivers/Akwa Ibom etc States gp AF-012 FT*J Juan De Nova Island AF-077 ZS Western Cape Province South group AF-013 5R Madagascar (Main Island Only) AF-078 6W Senegal South group AF-014 CT3 Madeira Archipelago AF-079 ZS Eastern Cape Province group AF-015 3B7 Saint Brandon Islands AF-080 E3 Red Sea Coast North group AF-016 FR Reunion Island AF-081 E3 Red Sea Coast South group AF-017 3B9 Rodrigues Island AF-082 3C Rio Muni Province group AF-018 IH9 Pantelleria Island AF-083 3V Gabes/Medenine Region group AF-019 IG9 Pelagie Islands AF-084 9G Ghana group AF-020 J5 Bijagos Archipelago AF-085 ZS Western Cape Province North West group AF-021 ZS8 Prince Edward & Marion Islands AF-086 D4 Cape Verde – Windward Islands AF-022 ZD7 -

The Island of Pantelleria (Sicily Strait, Italy): Towards the Establishment of a Marine Protected Area

BOLLETTINO DI GEOFISICA TEORICA ED APPLICATA VOL. 44, N. 1, PP. 3-9; MARCH 2003 The Island of Pantelleria (Sicily Strait, Italy): towards the establishment of a marine protected area. First oceanographic investigations F. BIANCHI and F. ACRI Istituto di Scienze Marine (ISMAR), Istituto di Biologia del Mare CNR, Venezia, Italy (Received, January 27, 200; accepted March 1, 200) Abstract - The Island of Pantelleria, located in the Sicily Strait (Italy), is not yet included on the list of Italian MPAs. A preliminary investigation about the hydrochemistry, at spatial and short-time scales, performed in late-summer 2001, is reported in this paper. Vertical, continuous measurements of temperature and salinity and discrete samplings of nutrients and chlorophyll a were carried out at 10 coastal stations. Results showed a strong thermal stratification, while the oligotrophic feature of the water column was pointed out by the low nutrients and chlorophyll a concentrations. Short-time T and S variations (every 10 minutes for 5 days) at a selected station, by a self-recording probe moored at a 22 m depth, showed a very dynamic pattern, probably driven by the tide. 1. Introduction The Island of Pantelleria, located in the middle of the Sicily Strait, 55 nautical miles from Cape Granitola (Italy) and 9 miles from Cape Bon (Tunisia), has an extension of 8 km, with a morphology derived mainly from ancient volcanic activities. The central area, with the highest mountain, Muntagna Grande (845.m high), is protected by a Naturally Oriented Reserve, managed by the Azienda Regionale Foreste Demaniali. As regards the marine environment, no Marine Protected Area (MPA) exists along its coasts, although a request was recently made by the local Municipality to the Ministry of the Environment, on November 2001. -

Gibilterra: Dominion Britannico in Un Territorio Dell'unione

PAOLO ROVATI GIBILTERRA: DOMINION BRITANNICO IN UN TERRITORIO DELL’UNIONE EUROPEA Gibilterra, per l’importante posizione strategica, è stata occupata mili- tarmente dagli inglesi nel 1704 ed è, ancor oggi, un dominion della corona britannica. Promontorio calcareo all’estremità meridionale della Penisola Iberica, proteso nel Mediterraneo, a picco sull’omonimo Stretto 1, comunemente chiamato The Rock in inglese e El Peñón in spagnolo, raggiunge un’altitu- dine massima di 426 m nell’Highest Point e degrada all’interno verso la Baia di Algeciras ad una latitudine di 36° 8’ nord e ad una longitudine di 5° 21’ ovest. È collegata alla terraferma da un istmo sabbioso, di 1,6 km di lunghezza e circa 800 m di larghezza, alla cui estremità sorge la città spa- gnola di La Línea de la Concepción. Il clima è temperato, con estati calde ed asciutte, con venti che spirano prevalentemente da est e da ovest (HUTT, 2005, p. 23); la vegetazione è piuttosto scarsa anche se ricca di ol- tre cinquecento specie, alcune delle quali endemiche (VERDÚ BAEZA, 2004, p. 343), ed è l’unico territorio europeo dove vivono scimmie in libertà (BRYSON, 1996, pp. 67 e 69). Copre una superficie di 6,5 kmq, con una po- polazione di 28.779 abitanti (2005) ed una densità di 4.427 ab/kmq 2. La lingua ufficiale è l’inglese, ma la maggior parte degli abitanti parla correntemente anche lo spagnolo. La popolazione è per il 78,1% cattolica, per il 7% protestante, per il 4% musulmana, per il 2,1% ebraica ed il re- stante 8,8% pratica altre religioni. -

E/Cnmc/005/18 Study on the Impact of Airfare Discounts in Non-Peninsular Territories

E/CNMC/005/18 STUDY ON THE IMPACT OF AIRFARE DISCOUNTS IN NON-PENINSULAR TERRITORIES 17 April 2020 CONTENTS www.cnmc.es ........................................................................................................................... 1 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.................................................................................... 5 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 9 2. LEGAL DESCRIPTION OF AID FOR ISLAND AIR TRANSPORT IN SPAIN 12 2.1. Partial airfare discount for resident travellers ...................................... 13 2.1.1. Airfare discount system for residents .......................................................... 13 2.1.2. Development of the partial airfare discount system for residents ................ 15 2.2. Other aid for island air transport .......................................................... 16 2.2.1. Public service obligations ............................................................................ 17 2.2.2. Discounted airport fees ............................................................................... 23 2.2.3. Start-up aid for airlines operating from the Canary Islands .......................... 25 3. ECONOMIC DESCRIPTION ...................................................................... 27 3.1. Routes between the Balearic Islands and the peninsula ..................... 31 3.1.1. Demand ...................................................................................................... 31 3.1.2. Supply -

Yachting - Yachtcharter Sicily: Lipari, Aegaedian Islands and Pantelleria

Barone Yachting - Yachtcharter Sicily: Lipari, Aegaedian Islands and Pantelleria Yacht - charter Yachtcharter Sicily: Lipari, Aegaedian Islands and Pantelleria Lipari Located in the Tyrrhenian Sea off the north coast of Sicily is an archipelago that is of volcanic origin. Also known as the Aeolian Islands the group of small volcanic rocks surrounding Lipari are a famous tourist destination and a sought after spot for yachting friends. The islands’ volcanic origin offers the observer a unique scenario as some of the mountains continue to blow smoke and deliver lava. Islands such as Stromboli, Salina or Vulcano are famous for their curious mixture of natural spectacle and charming tourism. Start from Porto Rosa or Palermo and witness this landscape in its totality. Your yacht will offer you the opportunity of seeing more than just one of the beautiful islands while evading stressful waiting procedures at a ferry. The area is also known for its mud baths and whoever is interested in experiencing such should just stop at the relevant sites. Aegadian Islands The Aegadian Islands were once the scene of major battles that ended the First Punic War. In the modern period the archipelago has come to be known for its excellent yachting waters and its fishing activities by the locals. Tuna is constantly being fished here on this group of islands which lies just some miles north-west of Sicily. The whole area of the archipelago covers a territory of about 15 square miles. The archipelago is constituted by three islands. Marettime and Favignana are quite big in size while Levanzo is the smallest island of the group. -

First Record of Percnon Gibbesi (H. Milne Edwards, 1853) (Crustacea: Decapoda: Percnidae) from Egyptian Waters

Aquatic Invasions (2011) Volume 5, Supplement 1: S123–S125 doi: 10.3391/ai.2010.5.S1.025 Open Access © 2010 The Author(s). Journal compilation © 2010 REABIC Aquatic Invasion Records First record of Percnon gibbesi (H. Milne Edwards, 1853) (Crustacea: Decapoda: Percnidae) from Egyptian waters Ernesto Azzurro1,2*, Marco Milazzo3, Francesc Maynou1, Pere Abelló1 and Tarek Temraz4 1Institut de Ciències del Mar (CSIC) Passeig Marítim de la Barceloneta, 37-49, E-08003 Barcelona, Spain 2High Institute for Environmental Protection and Research (ISPRA), Laboratory of Milazzo, Via dei Mille 44, 98057 Milazzo, Messina, Italy 3Dipartimento di Ecologia, Università di Palermo, via Archirafi 28, I-90123, Palermo, Italy 4Marine Science Department, Suez Canal University, Egypt E-mail: [email protected] (EA), [email protected] (MM), [email protected] (FM), [email protected] (PA), [email protected] (TT) *Corresponding author Received: 12 November 2010 / Accepted: 30 November 2010 / Published online: 22 December 2010 Abstract On July 2010, the invasive crab Percnon gibbesi was photographed and captured along the coast of Alexandria (Egypt, Eastern Mediterranean Sea). This represents the first observation of this species in Egyptian waters and the easternmost record for the southern rim of the Mediterranean. Key words: Percnon gibbesi, Percnidae, Egypt, Mediterranean, invasive species Mueller 2001). Subsequent records were from Introduction Sicilian shores (Pipitone et al. 2001; Mori and Vacchi 2002), Malta (Borg and Attard-Montalto The invasive crab Percnon gibbesi (H. Milne 2002), Tyrrhenian and Ionian shores of Italy Edwards, 1853) is one the most recent and successful invaders in the Mediterranean Sea. (Russo and Villani 2005; Faccia and Bianchi This species was formerly included within the 2007), Catalan Sea (Abelló et al. -

Psychosocial Experiences of African Migrants in Six European Countries a Mixed Method Study Social Indicators Research Series

Social Indicators Research Series 81 Erhabor Idemudia Klaus Boehnke Psychosocial Experiences of African Migrants in Six European Countries A Mixed Method Study Social Indicators Research Series Volume 81 Series Editor Alex C. Michalos, Faculty of Arts Office, Brandon University, Brandon, MB, Canada Editorial Board Ed Diener, Psychology Department, University of Illinois, Champaign, IL, USA Wolfgang Glatzer, J.W. Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main, Hessen, Germany Torbjorn Moum, University of Oslo, Blindern, Oslo, Norway Ruut Veenhoven, Erasmus University, Rotterdam, The Netherlands This series aims to provide a public forum for single treatises and collections of papers on social indicators research that are too long to be published in our journal Social Indicators Research. Like the journal, the book series deals with statistical assessments of the quality of life from a broad perspective. It welcomes research on a wide variety of substantive areas, including health, crime, housing, education, family life, leisure activities, transportation, mobility, economics, work, religion and environmental issues. These areas of research will focus on the impact of key issues such as health on the overall quality of life and vice versa.- An international review board, consisting of Ruut Veenhoven, Joachim Vogel, Ed Diener, Torbjorn Moum and Wolfgang Glatzer, will ensure the high quality of the series as a whole. Available at 25% discount for International Society for Quality-of-Life Studies (ISQOLS). For membership details please contact: ISQOLS; e-mail: office@isqols. org Editors: Ed Diener, University of Illinois, Champaign, USA; Wolfgang Glatzer, J.W. Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main, Germany; Torbjorn Moum, Univer- sity of Oslo, Norway; Ruut Veenhoven, Erasmus University, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. -

Cruising in Lampedusa & Linosa

Cruising in Lampedusa & Linosa SY Bonaire SY Miss Sophie August 2010 Pelagie Islands Map of Lampedusa & Linosa Itinerary 70 NM 25 NM Miss Sophie between Gozo and Linosa Big catch on Miss Sophie Wow!!! Approaching Linosa Linosa – Statistics and Information • 25NM north east of Lampedusa • Population: 450 • Surface area: 5.5 km2 • Highest point: Monte Vulcano at 195m • Volcanic, with dark lava rocks and beaches • Greener and more cultivated than Lampedusa • Though it lacks white beaches, sea is still incredibly transparent and full of marine life Linosa – Berthing / Anchoring • VHF: Tried many times but no answer • Scalo Vecchio is too small, narrow and awkward • Very limited berthing at inner quay in Cala Pozzolana di Ponente: drop anchor and tie stern to. However, very tricky and there are shallow boulders. Outer quay used by ferry • More practical to drop anchor: – SE at Cala Pozzolana di Levante, in prevailing NW winds – NW at Cala Pozzolana di Ponente, in south winds – N at Cala Mannarazza, but further away from Linosa village • Bottom is normally rocky with boulders of varying sizes • No water or fuel services • GPS error indicating boat crossing the island …. on land!! Linosa – Where to anchor Cala Mannarazza Cala Pozzolana di Ponente Scalo Vecchio Cala Pozzolana di Levante Linosa – Further information • Linosa is a lot quieter than Lampedusa and tourism is contained • Only tourist resort on the island closed a number of years ago • Houses are proudly very well kept • Islanders are reserved and very inter-related, so marriages with Lampedusans are not rare • Few shops and restaurants. One overlooking Scalo Vecchio was excellent • Because of the small numbers, there are no banks, so no credit cards and everything is paid in cash.