Copyright by Melanie Kathryn Haupt 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

E Il Quadri C'e' Sempre!

SOMMARIO anno secondo — numero terzo Ma se io avessi previsto tutto questo.. Pag.3 La caduta di Varsavia ... Pag.4 Antigone, tragedia immortale Pag.7 L’uomo, la bestia e la virtù”: realtà o apparenza Pag.9 Cento motivi x non ritirarsi dal Quadri Pag.10 IL peso dello zaino Pag.12 E meglio vivere o morire? Pag.13 I francobolli Pag.14 L’era glaciale Pag.15 Gin e Fizz, appuntamento noir Pag.16 Poesie Pag.17 Millencolin forever Pag.18 Tutti insieme appassionatamente Pag.20 Allarme HOAX Pag.21 Videogiochi & musica Pag.22 Orientamento lento Pag.24 Profémon Pag.26 171 Nomi Pag.28 Ritorna la pagella Pag.30 Direttore: Marco Azzalini 5^CI - [email protected] Il Giudizio Universale Vicedirettore: Arianna Frigo 4^AI - [email protected] Copertina di: SUPERVISORE ( NONCHé anima del giornalino ): Giuliano Guzzo 4^AI Giuliano Guzzo 4^AI - [email protected] Uomo obiettivo: Prof. Giuliano Cisco - [email protected] Impaginatori: Janusz Trevisan 4^AI - [email protected], Alessandro Venturini 5^CI [email protected], Cristian Pozza 3^AST, Gennaro Di Napoli 5^LG - [email protected], Gianluca Bonanno 5^LG, Gregorio Dal Sasso 2^BI - [email protected], Paolo Albanese 3^AST REDAZIONE: Giovanni Monarca 4^AST - [email protected], Andrea Pezzato 4^AST, Paola Bertozzi 3^BI, Trivisonno Andrea 1^AI, Paolo Zoccante 2^BI - [email protected], Mariasole Cavallarin 2^LG, Elisa Borrelli 5^CI, Stefano Tapparo 4^AST, Elisa Dalla Libera 2^LG, Valentina Accietto 3^BST, Guzzo Alberto 1^AI, Barbolan Cristina 1^BI, David Tosin 3^LG, Michele D’Alessandro 3^ATL, MariaGiulia Rigon 3^ATL Michael Walker “Texas Ranger” 4^AST Un ringraziamento particolare va rivolto al Comitato Genitori per il sostegno finanziario a questa pubblicazione Marco Azzalini 5^CI Vabbé, lo ammetto: cinque anni sono volati. -

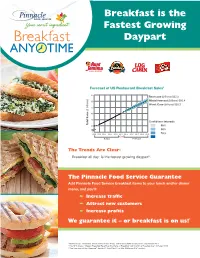

Breakfast Is the Fastest Growing Daypart

BreakfastBreakfast isis thethe FastestFastest GrowingGrowing DaypartDaypart Forecast of US Restaurant Breakfast Sales1 65 Best case (billions) $82.5 60 Mintel forecast (billions) $60.4 Worst Case (billions) $58.3 55 ($ billions) 50 45 Confi dence intervals Total Sales Total 40 95% 90% 0 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 70% Est. Actual Forecast The Trends Are Clear: • • Breakfast all day1 is the fastest growing daypart2. The Pinnacle Food Service Guarantee Add Pinnacle Food Service breakfast items to your lunch and/or dinner menu, and you’ll: ➨ Increase traffic ➨ Attract new customers ➨ Increase profits We guarantee it – or breakfast is on us!3 1 Mintel Group, “Breakfast Trends at Home and Away: The Morning Meal at Any Time”, September 2015 2 The NPD Group, “Classic Breakfast Fare Ride the Wave of Breakfast Visit Growth at Foodservice”, October 2015 3 One free case of Aunt Jemima®, Lender’s®, Log Cabin®, or Mrs. Butterworth’s® product. Breakfast Anytime Program Elements Here are all the tools you’ll need to serve Breakfast Anytime! • Menu Idea Guide – Recipes and menu ideas for breakfast and beyond. Menu Contest Get Creative and Get Rewarded - Enter the Breakfast Anytime Menu Contest! Menu Contest Grand • – Share your menu ideas and Prize $1,000 for You AND Peaches & Cream $1,000 for Your Local Food Bank! Stuffed French Toast* PLUS: 15 MORE CHANCES TO WIN! get a free case of product just for entering. 3 WINNERS FROM EACH OF 5 REGIONS – 1ST PRIZE: $500, 2ND PRIZE: $300, 3RD PRIZE: $200 See website for region map. -

STATEMENT of NONVIOLENCE (Page 1)

THE FOOD NOT BOMBS MOVEMENT STATEMENT OF NONVIOLENCE All Food Not Bombs volunteers work for nonviolent social change and this is our statement. The name Food Not Bombs states our most fundamental principle: That our society needs things that give life not things that give death. Our society is dominated by violence and the threat of violence. This affects us both in our daily lives through the constant threat of crime and police abuse and less directly but just as seriously through the threat of total annihilation from nuclear war. The authority and power of our government are predicated on the threat and use of violence. They continue to spend more time and resources developing, using, and threatening to use weapons of massive human and planetary destruction than on nurturing and celebrating life. Food Not Bombs has chosen to take a stand against violence. As a group of individuals we are committed to non-violent social change through the celebration and nurturing of life by giving out free vegetarian food. Poverty is violence. By spending money on bombs instead of addressing human needs, our government perpetuates and exacerbates the violence of poverty in our society. One of the most direct physical expressions of the violence of poverty is hunger. Millions of Americans go hungry every day and childhood malnutrition contributes heavily to infant mortality rates, which are higher in parts of the U.S. than in some Third World nations. Inadequate or non-existent health care, police brutality, and class discrimination are also forms of systemic violence against poor people. -

Bulletin 11 English Intro

BULLETIN 11 ENGLISH INTRO Since its first edition the “Reclaim the Fields” (RtF) bulletin is a way to exchange and circulate information within the RtF network and to make RtF and its ideas visible where it’s still less known. This Bulletin contains the outline and minutes of the meetings which took place during the last assembly in Warsaw. Furthermore you can find texts and other contributions from local networks and stars of the RtF constellation. The texts published in the bulletins reveal the diversity of the considerations and opinions that meet within RtF, and aim to feed reflection and mutual debate. The texts are the author’s responsibility, and don’t represent any position of RtF as a whole. Not all articles have been translated in all languages so not all bulletins are complete. For the next bulletin edition we need more support with translation ! So, if you would like to join the bulletin team please feel very welcome!! We need editors, translators, people that want to work on lay out and of course we like you to send articles, drawings, notes, invitations to actions etc.! Realize that it will be online and spread in many countries. Articles should be max. 2A4's (times new roman, font size 10). You can write in the language you prefer. We'll be happy if you can send it in several languages if possible. Thank you for sending your notes, the numerous articles and contributions! „los bulletin@s..“ [email protected] INDEX Who we are Part I: European winter assembly ROD Collective (Warsaw) # Report on the RtF European Winter assembly 21‐24 January 2016 ‐ At the ROD ‐ Warsaw # MINUTES 1. -

Pan Macmillan AUTUMN CATALOGUE 2021 PUBLICITY CONTACTS

Pan Macmillan AUTUMN CATALOGUE 2021 PUBLICITY CONTACTS General enquiries [email protected] Alice Dewing FREELANCE [email protected] Anna Pallai Amy Canavan [email protected] [email protected] Caitlin Allen Camilla Elworthy [email protected] [email protected] Elinor Fewster Emma Bravo [email protected] [email protected] Emma Draude Gabriela Quattromini [email protected] [email protected] Emma Harrow Grace Harrison [email protected] [email protected] Jacqui Graham Hannah Corbett [email protected] [email protected] Jamie-Lee Nardone Hope Ndaba [email protected] [email protected] Laura Sherlock Jess Duffy [email protected] [email protected] Ruth Cairns Kate Green [email protected] [email protected] Philippa McEwan [email protected] Rosie Wilson [email protected] Siobhan Slattery [email protected] CONTENTS MACMILLAN PAN MANTLE TOR PICADOR MACMILLAN COLLECTOR’S LIBRARY BLUEBIRD ONE BOAT MACMILLAN Nine Lives Danielle Steel Nine Lives is a powerful love story by the world’s favourite storyteller, Danielle Steel. Nine Lives is a thought-provoking story of lost love and new beginnings, by the number one bestseller Danielle Steel. After a carefree childhood, Maggie Kelly came of age in the shadow of grief. Her father, a pilot, died when she was nine. Maggie saw her mother struggle to put their lives back together. As the family moved from one city to the next, her mother warned her about daredevil men and to avoid risk at all cost. Following her mother’s advice, and forgoing the magic of first love with a high-school boyfriend who she thought too wild, Maggie married a good, dependable man. -

It Really Brightens up Hearty Vegetables, Like Broccolini, and Something Magical Happens When It’S Combined with All That Sauteed Garlic

And thank you for the support! A zine is about the here and now. As I am typing this we are seven months into the pandemic. The restaurant has been open for a bit, mostly for delivery. We have a little outdoor seating, in the form of a few hijacked parking spots out front. There are tables up and down the block and people don’t mind much. That’s how things are now. The city is allowing some indoor dining, but we won’t be doing that any time soon. But let’s go back a few decades for the back back story... Since the 80s, I’ve been cooking vegan food in Brooklyn as a way to bring people together. In the form of feminist potlucks or hosting brunches at any of the two dozen apartments I’ve lived in all over the borough. Feeding people in the park through volunteer organizations, or at fur-free Friday in the 90s. Even just cooking some latkes for my family at Hannukah. Really, any opportunity to serve people vegan food and I’m in. So having a vegan restaurant in Brooklyn, just a few blocks from where my grandfather grew up actually, was a natural culmination of passion, community and a sense of duty. A few years ago, when I was well into my forties, I was lucky enough to partner with Sara and Erica, whose family also has had ties to the neighborhood for decades and who also just want everyone to eat vegan. Well, great! A meal is born.. -

COOK for PEACE COOK for PEACE

COOK for PEACE COOK for PEACE With over a billion people going hungry each day how can we spend another dollar With over a billion people going hungry each day how can we spend another dollar on war? Food Not Bombs is one of the fastest growing revolutionary movements ac- on war? Food Not Bombs is one of the fastest growing revolutionary movements ac- tive in the world today. Food Not Bombs shares free vegan and vegetarian meals tive in the world today. Food Not Bombs shares free vegan and vegetarian meals with the hungry in over 1,000 cities around the world to protest war, poverty, and the with the hungry in over 1,000 cities around the world to protest war, poverty, and the destruction of the environment. Volunteers also organize food relief efforts for the sur- destruction of the environment. Volunteers also organize food relief efforts for the sur- vivors of natural disasters and people displaced by economic and political crisis. Vol- vivors of natural disasters and people displaced by economic and political crisis. Vol- unteers also provide food to the families of striking workers and people participating unteers also provide food to the families of striking workers and people participating in occupations, marches, and tent city protests. in occupations, marches, and tent city protests. The first group was formed in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1980 by eight college The first group was formed in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1980 by eight college aged anti-nuclear activists. Food Not Bombs is not a charity. It is an all volunteer aged anti-nuclear activists. -

Issue 4 2017.Indd

2017 Scholarship Winners • Vegan Yogurt Guide Science, Caring, and Vegan Living VEGETAJ OURNAL R IANSince 1982 Veganized VOLUME XXXVI, NO 4 Southern THICS 8 Global • E Dishes Fare COLOGY Cornbread • E Travel the EALTH Flapjacks & H world in Jalapeño a stew pot! Jelly pg. 22 $4.50 USA/$5.50 CANADA www.vrg.org Quick Pumpkin Dishes NUTRITION HOTLINE QUESTION: What’s the latest of their breast cancer recurring REED MANGELS, PhD, RD thinking about soy and the risk than women who did not of breast cancer or breast cancer eat soyfoods.3 Women eating recurrence? S.A. via email soyfoods also had a lower risk of death.3 There is some evidence ANSWER: Soyfoods contain that soy products may boost the substances called isoflavones, effects of common drugs used which have a chemical structure to treat breast cancer such as similar to the hormone estrogen. tamoxifen.1 Both the American This similarity is what initially led Cancer Society and the American to concerns that soyfoods could Institute for Cancer Research have increase the risk of breast cancer said that it’s fine for breast cancer or of breast cancer recurrence. survivors to eat soy.4,5 Recent research does not support these concerns. Asian women who References eat traditional diets that typically 1. Messina M. Impact of soy foods on include soy products, have a lower the development of breast cancer and risk for breast cancer than do the prognosis of breast cancer patients. Forsch Komplementmed. 2016;23(2):75- women in the United States who 80. typically eat few soy products.1 Of course, there are other differences 2. -

Mixing It Up, the Healthy

Nutrition Comparison Baking Mixes: A Nutrition Comparison As with all EN comparisons, this is only a sampling of what’s available. Products are listed alphabetically. Mixing It Up, the = EN’s Picks. Pancake/All Purpose mix picks contain no more than 160 calories (8% DV), 2 g total fat (3% DV), and 340 mg sodium (14% DV), and list a whole grain in the first two ingredients. Muffins/Cornbread Healthy Way mix picks contain no more than 170 calories (9% DV), 2 g total fat (3% DV), and 250 mg sodium (10% DV), and list a whole grain in the first two ingredients. Cake mix picks contain no more than 190 calories (10% here’s nothing like baking up some DV), 2 g total fat (3% DV), and 280 mg sodium (12% DV). Thomemade goodies. But there are days Serving Calories Fat Sat Sodium Carb Fiber Sugar Pro when you really want pancakes or need a Baking Mixes Size (g) Fat (g) (mg) (g) (g) (g) (g) party treat, but time is short. Fortunately, PANCAKE/ALL PURPOSE BAKING MIXES baking up some deliciousness is no harder Arrowhead Mills All Purpose Baking Mix* 1/3 c (40 g) 1 biscuit 130 1 0 390 28 2 2 5 than opening up a box and stirring in a few Aunt Jemima Buttermilk Complete 1/3 c (46 g) 4 pancakes 160 2 0.5 460 31 1 6 5 ingredients. An army of food companies Aunt Jemima Original Pancake & Waffle Mix 1/3 c (47 g) 4 pancakes 150 0.5 0 740 33 1 7 4 have done most of the work for you so you Aunt Jemima Whole Wheat Pancake & Waffle Mix* 1/4 c (38 g) 3 pancakes 120 0.5 0 620 26 3 4 4 can be a kitchen whiz in a fraction of the Bisquick Complete Pancake & Waffle Mix Simply time it would take to make it yourself. -

Pan-Cake-Mix-Syrup-Molasses Europe.Psa PANCAKE MIX /SYRUP and MOLASSES 8 FT

PANCAKE MIX /SYRUP AND MOLASSES 8 FT. SECTION (REVISED) HQ DeCA PLANOGRAM CLASS 3 / 4 / 5 STORES ADDED 41449-47149, -47150, 77391-71004 DELETED 41449-00128, -00297, 77391-71002 KRUSTEAZ ITEMS AVAILABLE 4/16/17 8.12 in Shelf: 1 11.12 in Shelf: 2 MRS IHOP BUTTER BUTTERWORTH COMPLETE 10.12 in PECAN SYRUP PANCAKE MIX LOG CABIN POUCH REGULAR SYRUP Shelf: 3 KRUSTEAZ 10.12 in BLUEBERRY PANCAKE MIX Shelf: 4 KRUSTEAZ HEART HEALTHY PANCAKES 11.12 in Shelf: 5 FLAP FLAP JACKED JACKED 11.12 in PROTEIN PROTEIN PNCAKE MX PNCAKE MX BABA CINN APPLE HAZELNT Shelf: Base 6 8 ft HQ DeCA/MBU PLANOGRAM APPROVED BY BUSINESS MANAGER, BARBARA MERRIWEATHER. MERCHANDISING SPECIALIST, ALEX Left-right WALDON. FACINGS MAY BE ADJUSTED TO ACCOMMODATE LOCAL AND REGIONAL ITEMS ( END OF FLOW). FACINGS MAY BE ADJUSTED TO MEET CUSTOMER 15 MARCH 2017 DEMAND-CAO MUST BE INVOLVED IN THE THE PROCESS ALONG WITH STORE MANAGEMENT APPROVAL. ITEM POSITIONS MUST NOT BE CHANGED AT ANY TIME. PanCakeMixSyrupMolasses- 8K3.psa Page: 1 of 4 PANCAKE MIX /SYRUP AND MOLASSES 8 FT. SECTION (REVISED) HQ DeCA PLANOGRAM CLASS 3 / 4 / 5 STORES ADDED 41449-47149, -47150, 77391-71004 DELETED 41449-00128, -00297, 77391-71002 KRUSTEAZ ITEMS AVAILABLE 4/16/17 MAPLE CARYS SUGAR FREE SYRUP CARYS CARYS PURE SOHGAVE SMUCKERS SMUCKE SMUCKE SMUCKERS SMUCKERS KARO GROVE MAPLE GROVE AGAVE RS RS KARO RED KARO MAPLE MAPLE GROVE BLUEBERRY SUGAR BOYSENBSTRAWBERR RED LIGHT SUGAR FREE MAPLE SYRUP ORGANIC MAPLE MAPLE SYRUP BLUE GRANDMA'S PURE MAPLE SYRUP BTL DARK SYRUP FREE ERRY Y RASPBERRY 8.12 in SYRUP SYRUP BLUEBER -

How Food Not Bombs Challenged Capitalism, Militarism, and Speciesism in Cambridge, MA Alessandra Seiter Vassar College, [email protected]

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2016 Veganism of a different nature: how food not bombs challenged capitalism, militarism, and speciesism in Cambridge, MA Alessandra Seiter Vassar College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Recommended Citation Seiter, Alessandra, "Veganism of a different nature: how food not bombs challenged capitalism, militarism, and speciesism in Cambridge, MA" (2016). Senior Capstone Projects. Paper 534. This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Veganism of a Different Nature How Food Not Bombs Challenged Capitalism, Militarism, and Speciesism in Cambridge, MA Alessandra Seiter May 2016 Senior Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts degree in Geography _______________________________________________ Adviser, Professor Yu Zhou Table of Contents Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................................. 2 Chapter 1: FNB’s Ideology of Anti-Militarism, Anti-Capitalism, and Anti-Speciesism ............ 3 Chapter 2: A Theoretical Framework for FNB’s Ideology .......................................................... 19 Chapter 3: Hypothesizing FNB’s Development -

Lundi / Monday

Lundi / Monday Restaurant Tamarind / Tamarind Restaurant Buffet Indien Indian Buffet Entrées Starters Raïta de concombre, oignons frits et menthe (V) Cucumber raïta with fried onions and mint (V) Dum aloo (Pommes de terre et petits pois) (V) Dum Aloo (Potatoes and peas) (V) Okra Bhindi (Gombos à la noix de coco grillée) (V) Okra Bhindi (Okra with grilled coconut) (V) Salade de chou-fleur et piment jalapeño (V) Cauliflower and jalapeño salad (V) Baingan Bharta (Aubergines à l’Indienne) (V) Baingan Bharta (Indian style eggplant) (V) Sambal d’oeufs durs aux petites crevettes Boiled eggs and bay shrimps sambal Salade de poulet façon tikka ´Tikka` style chicken salad Achard de citron (V) - Achard de mangue (V) Lemon pickle (V) - Mango pickle (V) Achard de légumes croquants (V) Crispy vegetable pickle (V) Achard de fruits de saison (V) Seasonal fruit pickle (V) Assortiment de pains - Buffet de crudités (V) Selection of breads - Salad bar (V) Assortiment de vinaigrettes (V) Selection of dressings (V) Soupes Soups Soupe de Mulugatawny au poulet Chicken Mulugatawny soup Soupe froide pastèque et tomate (V) Watermelon and tomato cold soup (V) Plats chauds Main dishes Rôti de boeuf, sauce au thym - Naans à l’ail (V) Roast beef with thyme sauce - Garlic naans (V) Poulet grillé - Sauce au beurre (V) Grilled chicken - Butter sauce (V) Vindaye de légumes (V) - Riz Dilla à l’Indienne (V) Vegetable vindaye (V) - Indian Dilla rice (V) Papadum - Purhi (Galettes de farine de blé) (V) Papadum - Purhi (Wheat flour pancakes) (V) Dholl safrané (V) Saffroned dholl