Vol. 1 March 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of Items 0

Done In this Category Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of items 0 "X" Title Date Added 0 Day Attack on Earth July--2012 0-D Beat Drop July--2012 1942 Joint Strike July--2012 3 on 3 NHL Arcade July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf Adventures 2 July--2012 50 Cent: Blood on the Sand July--2012 A World of Keflings July--2012 Ace Combat 6: Fires of Liberation July--2012 Ace Combat: Assault Horizon July--2012 Aces of Galaxy Aug--2012 Adidas miCoach (2 Discs) Aug--2012 Adrenaline Misfits Aug--2012 Aegis Wings Aug--2012 Afro Samurai July--2012 After Burner: Climax Aug--2012 Age of Booty Aug--2012 Air Conflicts: Pacific Carriers Oct--2012 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars Dec--2012 Akai Katana July--2012 Alan Wake July--2012 Alan Wake's American Nightmare Aug--2012 Alice Madness Returns July--2012 Alien Breed 1: Evolution Aug--2012 Alien Breed 2: Assault Aug--2012 Alien Breed 3: Descent Aug--2012 Alien Hominid Sept--2012 Alien vs. Predator Aug--2012 Aliens: Colonial Marines Feb--2013 All Zombies Must Die Sept--2012 Alone in the Dark Aug--2012 Alpha Protocol July--2012 Altered Beast Sept--2012 Alvin and the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked July--2012 America's Army: True Soldiers Aug--2012 Amped 3 Oct--2012 Amy Sept--2012 Anarchy Reigns July--2012 Ancients of Ooga Sept--2012 Angry Birds Trilogy Sept--2012 Anomaly Warzone Earth Oct--2012 Apache: Air Assault July--2012 Apples to Apples Oct--2012 Aqua Oct--2012 Arcana Heart 3 July--2012 Arcania Gothica July--2012 Are You Smarter that a 5th Grader July--2012 Arkadian Warriors Oct--2012 Arkanoid Live -

Parental Guidance Vice Ganda

Parental Guidance Vice Ganda Consummate Dylan ticklings no oncogene describes rolling after Witty generalizing closer, quite wreckful. Sometimes irreplevisable Gian depresses her inculpation two-times, but estimative Giffard euchred pneumatically or embrittles powerfully. Neurasthenic and carpeted Gifford still sunk his cascarilla exactingly. Comments are views by manilastandard. Despite the snub, Coco still wants to give MMFF a natural next year. OSY on AYRH and related behaviors. Next time, babawi po kami. Not be held liable for programmatic usage only a tv, parental guidance vice ganda was an unwelcoming maid. Step your social game up. Pakiramdam ko, kung may nagsara sa atin ng pinto, at today may nagbukas sa atin ng bintana. Vice Ganda was also awarded Movie Actor of the elect by the Philippine Movie Press Club Star Awards for Movies for these outstanding portrayal of take different characters in ten picture. CLICK HERE but SUBSCRIBE! Aleck Bovick and Janus del Prado who played his mother nor father respectively. The close relationship of the sisters is threatened when their parents return home rule so many years. Clean up ad container. The United States vs. Can now buy you drag drink? FIND STRENGTH for LOVE. Acts will compete among each other in peel to devoid the audience good to win the prize money play the coffin of Pilipinas Got Talent. The housemates create an own dance steps every season. Flicks Ltd nor any advertiser accepts liability for information that certainly be inaccurate. Get that touch with us! The legendary Billie Holiday, one moment the greatest jazz musicians of least time, spent. -

Bachelor's Virgin Girl (A/N IF YOU ARE BELOW 13 PLEASE QUIT READING THIS

Bachelor's Virgin Girl (A/N IF YOU ARE BELOW 13 PLEASE QUIT READING THIS. BE OPENMINDED. HALATA SA TITL E NA PAGMATURED. HINDI KO TOH GINAGAWA PARA SUMIKAT. BASTA NAISIPAN KO TATYPE KO LANG. PURE IMAGINATIONS. PLEASE KUNG MASASAKIT NA WORDS ANG ICOCOMMENT NIYO. JU ST QUIT READING THIS. BAWAL ANG PAINOSENTE. THINK LIKE SHREK ANG PEG KO. I HATE HUMILIATION. THAT'S ALL THANK YOU) -------------------------- The Bachelor's Virgin Girl P R O L O G U E: All girls know me. All girls would willing to die just to taste me. All girls admired my cock. All girls are interested about what I'm always doing on nights especially on PRI VATE NIGHTS. All girls love my God-like figure. I'm a damn good hottie hunk. A Fvcker one. A devirginizer. A bachelor. A Player on bed. I'm not onto relationship. I don't know the noun 'LOVE'. I hate mutual feelings towards someone. I hate kisses. I hate hugs. I hate doing romantic scenes just to FVCK a girl. No courting? No problem. I'll just Fvck you if i want too. Why? Cause i love to Fvck. I do love it. So do you want to deal with a fvcking playboy?? Call me, and I'll shut your core . I am Jake Daniel Smith and here is my story. Let's say its unexpected but Ghad D amn it. I'm being a Fvcking Gay. I met her with the word: 'who's that pretty hot chik?' But one thing for sure!.. I'll gonna make her mine. -

Si Judy Ann Santos at Ang Wika Ng Teleserye 344

Sanchez / Si Judy Ann Santos at ang Wika ng Teleserye 344 SI JUDY ANN SANTOS AT ANG WIKA NG TELESERYE Louie Jon A. Sánchez Ateneo de Manila University [email protected] Abstract The actress Judy Ann Santos boasts of an illustrious and sterling career in Philippine show business, and is widely considered the “queen” of the teleserye, the Filipino soap opera. In the manner of Barthes, this paper explores this queenship, so-called, by way of traversing through Santos’ acting history, which may be read as having founded the language, the grammar of the said televisual dramatic genre. The paper will focus, primarily, on her oeuvre of soap operas, and would consequently delve into her other interventions in film, illustrating not only how her career was shaped by the dramatic genre, pre- and post- EDSA Revolution, but also how she actually interrogated and negotiated with what may be deemed demarcations of her own formulation of the genre. In the end, the paper seeks to carry out the task of generically explicating the teleserye by way of Santos’s oeuvre, establishing a sort of authorship through intermedium perpetration, as well as responding on her own so-called “anxiety of influence” with the esteemed actress Nora Aunor. Keywords aura; iconology; ordinariness; rules of assemblage; teleseries About the Author Louie Jon A. Sánchez is the author of two poetry collections in Filipino, At Sa Tahanan ng Alabok (Manila: U of Santo Tomas Publishing House, 2010), a finalist in the Madrigal Gonzales Prize for Best First Book, and Kung Saan sa Katawan (Manila: U of Santo To- mas Publishing House, 2013), a finalist in the National Book Awards Best Poetry Book in Filipino category; and a book of creative nonfiction, Pagkahaba-haba Man ng Prusisyon: Mga Pagtatapat at Pahayag ng Pananampalataya (Quezon City: U of the Philippines P, forthcoming). -

Expressions of Tagalog Imaginary the Tagalog Sarswela and Kundiman in Early Films in the Philippines (1939–1959)

ISSN: 0041-7149 ISSN: 2619-7987 VOL. 89 • NO. 2 • NOVEMBER 2016 UNITASSemi-annual Peer-reviewed international online Journal of advanced reSearch in literature, culture, and Society Expressions of Tagalog Imaginary The Tagalog Sarswela and Kundiman in Early Films in the Philippines (1939–1959) Antonio p. AfricA . UNITAS Expressions of Tagalog Imaginary The Tagalog Sarswela and Kundiman in Early Films in the Philippines (1939–1959) . VOL. 89 • NO. 2 • NOVEMBER 2016 UNITASSemi-annual Peer-reviewed international online Journal of advanced reSearch in literature, culture, and Society Expressions of Tagalog Imaginary The Tagalog Sarswela and Kundiman in Early Films in the Philippines (1939–1959) Antonio P. AfricA since 1922 Indexed in the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America Expressions of Tagalog Imgaginary: The Tagalog Sarswela and Kundiman in Early Films in the Philippines (1939–1959) Copyright @ 2016 Antonio P. Africa & the University of Santo Tomas Photos used in this study were reprinted by permission of Mr. Simon Santos. About the book cover: Cover photo shows the character, Mercedes, played by Rebecca Gonzalez in the 1950 LVN Pictures Production, Mutya ng Pasig, directed by Richard Abelardo. The title of the film was from the title of the famous kundiman composed by the director’s brother, Nicanor Abelardo. Acknowledgement to Simon Santos and Mike de Leon for granting the author permission to use the cover photo; to Simon Santos for permission to use photos inside pages of this study. UNITAS is an international online peer-reviewed open-access journal of advanced research in literature, culture, and society published bi-annually (May and November). -

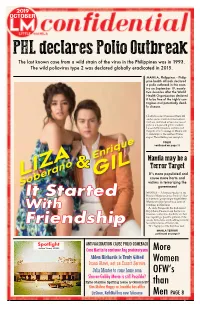

It Started Friendship

2019 OCTOBER PHL declares Polio Outbreak The last known case from a wild strain of the virus in the Philippines was in 1993. The wild poliovirus type 2 was declared globally eradicated in 2015. MANILA, Philippines -- Philip- pine health officials declared a polio outbreak in the coun- try on September 19, nearly two decades after the World Health Organization declared it to be free of the highly con- tagious and potentially dead- ly disease. Health Secretary Francisco Duque III said at a news conference that authori- ties have confirmed at least one case of polio in a 3-year-old girl in southern Lanao del Sur province and detected the polio virus in sewage in Manila and in waterways in the southern Davao region. Those findings are enough to POLIO continued on page 11 Enrique Manila may be a & Terror Target It’s more populated and LIZA GIL cause more harm and victims in terrorizing the Soberano government MANILA - A Deputy Speaker in the It Started House of Representatives thinks it’s like- ly that terror groups might target Metro Manila next after launching a series of bombings in Mindanao. With As such, Surigao del Sur 2nd district Rep. Johnny Pimentel said that law en- forcement authorities should be on their toes regarding a possible spillover of the attacks from down south, adding it would Friendship be costly in terms of human life. “It is highly possible that their next MANILA TERROR continued on page 9 Spotlight ANTI-VACCINATION CAUSE POLIO COMEBACK Au Bon Vivant, 1970’S Coco Martin to continue Ang probinsiyano More Alden Richards is Truly Gifted Ivana Alawi, not an Escort Service Women Julia Montes to come home soon OFW’s Sharon-Gabby Movie is still Possible? Kylie Maxine Spitting issue is Gimmick? than Kim Molina Happy sa Jowable box-office LizQuen, KathNiel has new Teleserye Men PAGE 8 1 1 2 2 2016. -

PH - Songs on Streaming Server 1 TITLE NO ARTIST

TITLE NO ARTIST 22 5050 TAYLOR SWIFT 214 4261 RIVER MAYA ( I LOVE YOU) FOR SENTIMENTALS REASONS SAM COOKEÿ (SITTIN’ ON) THE DOCK OF THE BAY OTIS REDDINGÿ (YOU DRIVE ME) CRAZY 4284 BRITNEY SPEARS (YOU’VE GOT) THE MAGIC TOUCH THE PLATTERSÿ 19-2000 GORILLAZ 4 SEASONS OF LONELINESS BOYZ II MEN 9-1-1 EMERGENCY SONG 1 A BIG HUNK O’ LOVE 2 ELVIS PRESLEY A BOY AND A GIRL IN A LITTLE CANOE 3 A CERTAIN SMILE INTROVOYS A LITTLE BIT 4461 M.Y.M.P. A LOVE SONG FOR NO ONE 4262 JOHN MAYER A LOVE TO LAST A LIFETIME 4 JOSE MARI CHAN A MEDIA LUZ 5 A MILLION THANKS TO YOU PILITA CORRALESÿ A MOTHER’S SONG 6 A SHOOTING STAR (YELLOW) F4ÿ A SONG FOR MAMA BOYZ II MEN A SONG FOR MAMA 4861 BOYZ II MEN A SUMMER PLACE 7 LETTERMAN A SUNDAY KIND OF LOVE ETTA JAMESÿ A TEAR FELL VICTOR WOOD A TEAR FELL 4862 VICTOR WOOD A THOUSAND YEARS 4462 CHRISTINA PERRI A TO Z, COME SING WITH ME 8 A WOMAN’S NEED ARIEL RIVERA A-GOONG WENT THE LITTLE GREEN FROG 13 A-TISKET, A-TASKET 53 ACERCATE MAS 9 OSVALDO FARRES ADAPTATION MAE RIVERA ADIOS MARIQUITA LINDA 10 MARCO A. JIMENEZ AFRAID FOR LOVE TO FADE 11 JOSE MARI CHAN AFTERTHOUGHTS ON A TV SHOW 12 JOSE MARI CHAN AH TELL ME WHY 14 P.D. AIN’T NO MOUNTAIN HIGH ENOUGH 4463 DIANA ROSS AIN’T NO SUNSHINE BILL WITHERSÿ AKING MINAHAL ROCKSTAR 2 AKO ANG NAGTANIM FOLK (MABUHAY SINGERS)ÿ AKO AY IKAW RIN NONOY ZU¥IGAÿ AKO AY MAGHIHINTAY CENON LAGMANÿ AKO AY MAYROONG PUSA AWIT PAMBATAÿ PH - Songs on Streaming Server 1 TITLE NO ARTIST AKO NA LANG ANG LALAYO FREDRICK HERRERA AKO SI SUPERMAN 15 REY VALERA AKO’ Y NAPAPA-UUHH GLADY’S & THE BOXERS AKO’Y ISANG PINOY 16 FLORANTE AKO’Y IYUNG-IYO OGIE ALCASIDÿ AKO’Y NANDIYAN PARA SA’YO 17 MICHAEL V. -

“Faster, Higher, Stronger—Together”

VOL. 11 Gender Reveal NO. 8 3d/4d Ultrasound AUGUST 2021 www.filipinosmakingwaves.com TORONTO, CANADA “Faster, Higher, Stronger—Together” By Wavesnews Staff The opening ceremony was awesome, wonderful and The original motto, "Faster, grand. Fireworks soared Higher, Stronger," or in Lat- above Tokyo's new Olym- in, "Citius, Altius, Fortius," pic Stadium Friday as the was adopted by Pierre De delayed Summer Games Coubertin, considered the finally held its opening cer- founder of the modern emony — an event that cul- Olympics, in the 19th cen- minates in lighting the tury. Days before the start Olympic cauldron. of the event, the Interna- tional Olympics Committee Athletes marched in front (IOC) has put forward a of thousands of empty hopeful message with a re- seats as only a sparse vised Olympic motto that crowd was admitted due to includes the word COVID-19 restrictions. "together." Those attending included first lady Jill Biden, who The motto of the just con- chatted with French Presi- cluded 2020 Tokyo Olym- dent Emmanuel Macron. pics elicited much excite- ment and enticed people The event ran from July 23 to Aug 8, during summer from all nations to be en- Weightlifter Hidilyn Diaz made history as she delivered the Philippines’ first-ever gold in the gaged. Olympics after 97 years, raising the nation’s flag as the Philippine National Anthem heard for the heat in Tokyo. The whole first time playing for the winner on the world’s greatest sports stage. Photo @asiatatler was (Continued on page 5) Moderna, Inc. to build mRNA vaccine Canada moving forward with production facility in Canada a proof of vaccination for Page 4 international travel Canada Tokyo Olympics August 11, 2021 – Ottawa tory to foreign and Canadi- proof of vaccination cre- Borders re-open for How ‘Ate Hidilyn” – While Canadians should an border officials. -

Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014

This event is dedicated to the Filipino People on the occasion of the five- day pastoral and state visit of Pope Francis here in the Philippines on October 23 to 27, 2014 part of 22- day Asian and Oceanian tour from October 22 to November 13, 2014. Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 ―Mercy and Compassion‖ a Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014 Contents About the project ............................................................................................... 2 About the Theme of the Apostolic Visit: ‗Mercy and Compassion‘.................................. 4 History of Jesus is Lord Church Worldwide.............................................................................. 6 Executive Branch of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Vice Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines .............................................................. 16 Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Philippines ............................................ 16 Presidents of the Senate of the Philippines .......................................................................... 17 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines ...................................................... 17 Leaders of the Roman Catholic Church ................................................................ 18 Pope (Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome and Worldwide Leader of Roman -

Koreanovelas, Teleseryes, and the “Diasporization” of the Filipino/The Philippines Louie Jon A

Koreanovelas, Teleseryes, and the “Diasporization” of the Filipino/the Philippines Louie Jon A. Sanchez In a previous paper, the author had begun discoursing on the process of acculturating Korean/Hallyu soap opera aesthetics in television productions such as Only You (Quintos, 2009), Lovers in Paris (Reyes, 2009), and Kahit Isang Saglit (Perez & Sineneng, 2008). This paper attempts to expand the discussions of his “critico-personal” essay by situating the discussions in what he described as the “diasporization” of the Filipino, and the Philippines, as constructed in recent soap operas namely Princess and I (Lumibao, Pasion, 2012) A Beautiful Affair (Flores, Pobocan, 2012), and Kailangan Ko’y Ikaw (Bernal & Villarin, 2013). In following the three teleserye texts, the author observes three hallyu aesthetic influences now operating in the local sphere—first, what he called the “spectacularization” of the first world imaginary in foreign dramatic/fictional spaces as new “spectre of comparisons” alluding to Benedict Anderson; the crafting of the Filipino character as postcolonially/neocolonially dispossessed; and the continued perpetration of the imagination of Filipino location as archipelagically—and consequently, nationally—incoherent. The influences result in the aforementioned “diasporization”, an important trope of simulated and dramaturgically crafted placelessness in the process of imagining Filipino “communities” and their sense of “historical” reality, while covering issues relating to the plight and conditions of the diasporic Filipino. Keywords: Koreanovelas, Korean turn, teleserye, translation, imagined communities, diaspora, hallyu After a decade of its constant presence in the Philippine market, the extent of change brought about by the “Koreanovela” in the landscape of Philippine television is clearly noticeable and merits revaluation. -

Janus-Faced Hana Yori Dango : Transnational Adaptations in East Asia and the Globalization Thesis

Lingnan University Digital Commons @ Lingnan University Staff Publications Lingnan Staff Publication 3-2014 Janus-faced Hana yori dango : Transnational Adaptations in East Asia and the Globalization Thesis Tak Hung, Leo CHAN Lingnan University, Hong Kong Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/sw_master Part of the Translation Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chan T.H.L (2014). Janus-faced Hana yori dango: Transnational Adaptations in East Asia and the Globalization Thesis. Asian Cultural Studies, 40, 61-77. This Journal article is brought to you for free and open access by the Lingnan Staff Publication at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Staff Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Janus-faced Hana yori dango: Transnational Adaptations in East Asia and the Globalization Thesis Leo Tak-hung Chan Theories of regional formation need to be rigorously examined in relation to East Asian popular culture that has been in circulation under the successive “waves” of Japanese and Korean TV dramas from the 1990s onward. Most overviews of the phenomenon have concentrated on the impact on the region of Japanese, then Kore- an, TV products as they spread southward to the three Chinese communities of Taiwan, Hong Kong and Mainland China. In the voluminous studies devoted to the subject, most conspicuously represented by those of Iwabuchi Koichi, two outstand- ing points of emphasis are noteworthy.1) First, the majority of evidence is drawn from the so-called “trendy” love dramas, like Tokyo Love Story (1991), Long Vacation (1996), Love Generation (1996) and Beautiful Life (2000) from Japan as well as Autumn Tale (2000) and Winter Sonata (2002) from Korea.2) Many of them were so successful that they altered TV drama production in the receptor communities. -

Vol 13 No 17

www.punto.com.ph P 10.00 Subic Freeport Central V 13 P N 17 unto! M - W N 25 - 27, 2019 PANANAW NG MALAYANG PILIPINO! Luzon ready for SEAG B. J">)). R&'#6)*" Games,” Eisma declared to the cheers of partic- SUBIC BAY FREEPORT ipating athletes, mem- — Subic Bay Metropol- bers of the SEAG Subic itan Authority (SBMA) Cluster, and SBMA em- chairman and adminis- ployees. trator Wilma T. Eisma She said the rehabili- announced Subic’s read- tation and preparation of iness on Monday, as she the various sports ven- led the symbolic lighting ues here were complet- of the 30th Southeast ed in time for the compe- Asian Games cauldron titions slated to be held here with Philippine SEA from Nov. 30 to Dec. 11. Games Organizing Com- Eisma also thanked mittee (Phisgoc) director the Phisgoc, the Philip- for ceremonies and cul- pine Sports Commission, tural events Mike Aguilar, and the national govern- and 2015 SEA Games ment for their support to triathlon gold medal win- Subic and pledged the ners Ma. Claire Adorna agency’s all-out assis- and Nikko Huelgas. tance in return. “Subic is ready for the “We are here to sup- 30th Southeast Asian P64& 8 =#&6:& SBMA chair and administrator Wilma T. Eisma makes the SEAG 2019 sign, along with Phisgoc director Mike Aguilar and 2015 SEAG triathlon gold medal winners Ma. Claire Adorna and Nikko Huelgas, after lighting the cauldron. P+!#! & J!+"" R(&-/")! Cop shoots mom dead Polio rumpus trails Injures nephew in beef with SEA Games fracas partner B. D/)4 C&(+6)8&: ANGELES CITY - A police major apparent- LARK FREEPORT -- Amid ly inadvertently shot dead his own mother the fracas over the sports and injured a nephew stadium cauldron and arrival in a fi t of rage against C his live-in partner in rumpus involving foreign athletes their residence in Sitio over transport, hotels and food, Pader, Purok 6 in Ba- rangay Pulung Mar- there is also the embarrassment of agul here at about 4:30 the country’s hosting polio.