Scotland's First Settlers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scotland's First Settlers

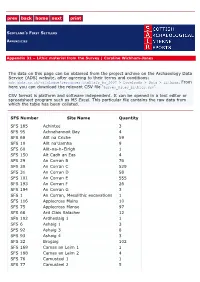

prev back home next print SCOTLAND’S FIRST SETTLERS APPENDICIES Appendix 31 – Lithic material from the Survey | Caroline Wickham-Jones The data on this page can be obtained from the project archive on the Archaeology Data Service (ADS) website, after agreeing to their terms and conditions: ads.ahds.ac.uk/catalogue/resources.html?sfs_ba_2007 > Downloads > Data > Lithics. From here you can download the relevant CSV file ‘Survey_Sites_Lithics.csv’. CSV format is platform and software independent. It can be opened in a text editor or spreadsheet program such as MS Excel. This particular file contains the raw data from which the table has been collated. SFS Number Site Name Quantity SFS 185 Achintee 3 SFS 95 Achnahannait Bay 4 SFS 68 Allt na Criche 59 SFS 10 Allt na'Uamha 9 SFS 60 Allt-na-h-Eirigh 1 SFS 150 Alt Cadh an Eas 4 SFS 29 An Corran B 76 SFS 30 An Corran C 529 SFS 31 An Corran D 58 SFS 101 An Corran E 555 SFS 193 An Corran F 26 SFS 194 An Corran G 3 SFS 1 An Corran, Mesolithic excavations 1 SFS 116 Applecross Mains 10 SFS 75 Applecross Manse 97 SFS 66 Ard Clais Salacher 12 SFS 102 Ardheslaig 1 1 SFS 6 Ashaig 1 3 SFS 92 Ashaig 3 8 SFS 93 Ashaig 4 3 SFS 32 Brogaig 102 SFS 168 Camas an Leim 1 1 SFS 188 Camas an Leim 2 4 SFS 76 Camusteel 1 1 SFS 77 Camusteel 2 5 SFS 17 Church Cave 4 SFS 61 Clachan Church 3 SFS 99 Clachan Church Midden 1 SFS 147 Cnoc na Celpeirein 41 SFS 89 Coire Sgamadail 1 7 SFS 90 Coire Sgamadail 3–6 8 SFS 49 Creag na-h-Uamha 2 SFS 2 Crowlin 1 31 SFS 22 Crowlin 3 60 SFS 23 Crowlin 4 1 SFS 26 Crowlin 7 4 SFS 190 Diabeg -

Loch Shianta Staffin Island / Fladda Flodigarry Island

LOCH SHIANTA From the Statistical Account 1791-99, by the Rev. Donald Martin, p. 556 In a low valley, there is a small hill, shaped like a house, and covered with small trees, or rather shrubs, of natural growth. At one side of it, there is a lake of soft water, from which there is no visible discharge. Its water finds many passages through the hill, and makes its appearance, on the other side, in a great number of springs, of the very purest kind. They all run into an oval bason (sic) below, which has a bottom of white sand, and is the habitation of many small fish. From that pond, the water runs, in a copious stream, to the sea. At the side of this rivulet, there is a bath, made of stone, and concealed from public view, by small trees surrounding it. Its name is Loch Shianta, or the sacred lake. There was once a great resort of people, afflicted with ailments, to this place. They bathed themselves, and drank of the water, though it has no mineral quality; and, on a shelf, made for the purpose, in the wall of a contiguous inclosure, they left offerings of small rags, pins, and coloured threads, to the divinity of the place. STAFFIN ISLAND / FLADDA About three Leagues to the North West of Rona, is the Isle Fladda being almost joyn’d to Skie, it is all plain arable Ground, and about a Mile in Circumference. FLODIGARRY ISLAND / ALTVIG A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland 1703 by Martin Martin About a Mile to the North, lies the Isle Altvig, it has a high Rock facing the East, is near two Miles in circumference, and is reputed fruitful in Corn and Grass, there is a little old Chappel in it, dedicated to St. -

Scotland's First Settlers 1999 Data Structure Report

CENTRE for FIELD ARCHAEOLOGY University of Edinburgh August 1999 Grant aided by The British Academy The Society of Antiquaries of Scotland The Society of Antiquaries of London The Percy Hedley Foundation The Russell Trust The Prehistoric Society The Applecross Trust Scotland’s First Settlers 1999 Data Structure Report This document has been prepared in accordance with CFA standard operating procedures. Authors: B Finlayson Date K Hardy CR Wickham-Jones Contributors: R Ceron M Cressey J Thoms Approved by: Date Draft/Final Report Stage: FINAL Centre for Field Archaeology Old High School 12 Infirmary Street Edinburgh EH1 1LT Tel: 0131-650-8197 Fax: 0131-662-4094 CONTENTS 0. Summary 4 1. Introduction 5 2. Sampling Strategy 9 3. Methods 10 4. Archaeological Results 13 5. Survey Results 20 6. Artefact Studies 25 7. Environmental Studies 38 8. Palaeo-environmental assessment of the Ecofacts 39 9. Discussion 42 10. Recommendations 44 11. References 47 Appendices 1. List of Cartographic Sources 48 2. List of Sites 49 3. List of Context 53 4. List of Finds 56 4.1 Bone Tools 56 4.2 Coarse Stone Tools 57 4.3 Flaked Lithics 58 4.4 Other Finds 73 5. List of Field Drawings 74 6. List of Photographs 75 7. Crowlin Samples Register 77 8. Sand Samples Register 78 9. Ashaig Samples Register 79 10. Loch a Sguirr Samples Register 79 11. Palaeo-environmental Rapid Scan Assessment, Crowlin 80 12. Palaeo-environmental Rapid Scan Assessment, Sand 82 13. Palaeo-environmental Rapid Scan Assessment, Loch a Sguirr 85 14. Palaeo-environmental Rapid Scan Assessment, Ashaig 86 Illustrations Fig. -

O Rth East Skye

7 k . u 2 h. 0 lso 1 a c N h . c m o f L n i l dl DUNTULMn i a u 7 e c . y : FLODIGARRY o 2 k e 0 S n 1 l i g n Flora n o i MacDonald's QUIRAING v n r e Monument r e t S s l i KILMUIR T STAFFIN t UIG R O h T L i T E CU R N E GLENHINNISDALE I S H a ORNISH KENSALEYRE Old Man s of Storr E t BERNISDALE S S S k Snap shot y Spectacular landscape and incredible rock formations make a leisurely drive through e the North East of Skye a must do for any itinerary 56 The Kilmartin Mon–Sat 10am–5pmLic etnhseend R6 e–s8ta.u3r0anptm /Café Good Scottish Fayre • Homebaking (made on site) ContaFcrte Msho Braargis otan C 0of1fe4e7 •0T 5ak6e2a3w2a2y Fish & Chips, etc Find uLso cianl ASrttas fafnind CCroamftsm • uChniiltdyre Hn aWlel,l cSotmae ffin (OPEN UNTIL 9pm DURING AUGUST) Check out The Visitor website at www.welcometothehighlands.com ! ! Ellishadder ART CAFE Ellishadder Art Café offers irresistible home baking, mouth-watering meals using fresh local produce, original artwork, a luxury range of handmade gifts and a warm welcome! We look forward to seeing you soon! ! dogs welcome ! credit cards accepted ! Ellishadder, Nr Staffin, Isle of Skye IV51 9JE 01470 562734 www.ellishadderartcafe.co.uk 57 58 Published by West Highland Publishing Company Limited, Pairc nan Craobh, Broadford, Isle of Skye IV49 9AP TRACK LISTING 1 The Loch Tay Boat Song 2 Introduction The FREE V THE 3 South West Ross – Lochcarron, Plockton, Kyle 4 North West Ross – north of Lochcarron to Ullapool Holiday Guide 5 South Skye, Sleat and Mallaig 6 Portree, Central Skye and Raasay to -

An Corran, Staffin, Skye: a Rockshelter with Mesolithic and Later Occupation

AN CORRAN, STAFFIN, SKYE: A ROCKSHELTER WITH MESOLITHIC AND LATER OCCUPATION Alan Saville,1 Karen Hardy,2 Roger Miket3 and Torben Bjarke Ballin4 With contributions by László Bartosiewicz, Clive Bonsall, Margaret Bruce, Stephen Carter, Trevor Cowie, Oliver Craig, Ywonne Hallén, Timothy G. Holden, N.W. Kerr, Jennifer Miller, Nicky Milner, and Catriona Pickard, and with illustrations by Alan Braby, Marion O’Neil, and Craig Angus 1 Corresponding author. Scottish History and Archaeology Department, National Museums Scotland, Chambers Street, Edinburgh, EH1 1JF, Scotland [email: [email protected]] 2 ICREA, Institució Catalana de Recerca I Estudis Avançats, Departament de Pre- història, Facultat de Filosofia i Lletres, Campus UAB, 08193 Bellaterra, Barcelona, Spain [email: [email protected]] 3 The Miller’s House, Yearle Mill, Wooler, Northumberland, NE71 6RA, England. [email: [email protected]] 4 Lithic Research, Banknock Cottage, Denny, Stirlingshire, FK6 5NA, Scotland [email: [email protected]] Scottish Archaeological Internet Report 51, 2012 www.sair.org.uk Published by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, www.socantscot.org.uk with Historic Scotland, www.historic-scotland.gov.uk and the Council for British Archaeology, www.britarch.ac.uk Editor Helen Bleck Produced by Archetype Informatique SARL, www.archetype-it.com ISBN: 978-1-908332-99-8 ISSN: 1773-3803 Requests for permission to reproduce material from a SAIR report should be sent to the Director of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, as well as to the author, illustrator, photographer or other copyright holder. Copyright in any of the Scottish Archaeological Internet Reports series rests with the SAIR Consortium and the individual authors. -

Scottish Islands

This is the definitive list for Scottish Islandbaggers. (Islandbagging = The obsessive compulsion to visit island summits.) Rick Livingstone’s Tables of THE ISLANDS OF SCOTLAND ¾ A register of all islands 15 hectares, or more, in area. That’s 37 acres, and roughly equates to a circular island ¼ of a mile across. ¾ Includes tidal islands, islands which are bridged or have cause-ways and freshwater islands. Comments & suggestions welcome: e-mail: [email protected] or landmail to: Rick Livingstone, Overend House, Greysouthen, Cockermouth, Cumbria, CA130UA, U.K. © Rick Livingstone 2011 [v300111] THE ISLANDS OF SCOTLAND IN REGIONAL ORDER Name Region Location O.S. Grid ref Summit name Height Area & No. Map (summit) (metres) Region 1. Solway & the Clyde 1. Ardwall Island 1.1 Gatehouse of Fleet 83 572-493 - none - 34 19h 2. Ailsa Craig 1.2 SE of Arran 76 018-999 The Cairn 338 99h 3. Sanda 1.3 S of Kintyre 68 730-044 - none - 123 1.2km2 4. Davaar 1.4 Campbeltown 68 758-200 - none - 115 1km2 5. Holy Island 1.5 E of Arran 69 063-298 Mullach Mor 314 2.5km2 6. Arran 1.6 East of Kintyre 69 416-992 Goat Fell 874 430km2 7. Little Cumbrae 1.7 SE of Bute 63 143-514 Lighthouse Hill 123 3.5km2 8. Great Cumbrae 1.8 SE of Bute 63 169-570 Barbay Hill 127 11km2 9. Inchmarnock 1.9 W of Bute 63 019-602 - none - 60 2.5km2 10. Bute 1.10 N of Arran 63 043-699 Windy Hill 278 120km2 Region 2. -

Pabay (Harris), Pabaigh

Iain Mac an Tàilleir 2003 94 Pabay (Harris), Pabaigh. Peinness (Skye), Peighinn an Easa. "Priest island", from Norse. A native of "The pennyland by the waterfall or stream". Pabay was a Pabach or cathan, "sea bird". Penbreck (Ayr). Pabbay (Barra, Skye), Pabaigh. "Speckled pennyland", from Peighinn Breac. See Pabay. Penick (Nairn). Paible (North Uist), Paibeil. This may be "small pennyland", from "Priest village", from Norse. A saying warns, Peighinneag. Na toir bó á Paibeil, 's na toir bean á Penifiler (Skye), Peighinn nam Fìdhleir. Boighreigh, "Don't take a cow from Paible or "The pennyland of the fiddlers". a wife from Boreray". Peninerine (South Uist), Peighinn nan Paiblesgarry (North Uist), Paiblisgearraidh. Aoireann. "The pennyland at the raised "Fertile land of Paible", from Norse. beaches". Pairc (Lewis), A' Phàirc. Pennycross (Mull), Peighinn na Croise. "The park". The full name is A' Phàirc "The pennyland of the cross", the cross in Leódhasach, "the Lewis Park". question being Crois an Ollaimh, known as Paisley (Renfrew), Pàislig. "Beaton's Cross" in English. "Basilica". Pennyghael (Mull), Peighinn a' Ghaidheil. Palascaig (Ross), Feallasgaig. "The pennyland of the Gael". "Hilly strip of land", from Norse. Pensoraig (Skye), Peighinn Sòraig. Palnure (Kirkcudbright). "Pennyland by the muddy bay", from Gaelic/ This may be "the pool by the yew tree or Norse. trees", from Poll an Iubhair or Poll nan Pentaskill (Angus). Iubhar, but see Achanalt. "Land of the gospel", from Pictish pett and Panbride (Angus). Gaelic soisgeul. "Bridget's hollow", with Brythonic pant, Persie (Perth), Parasaidh or Parsaidh. "hollow", or a gaelicised version giving Pann See Pearsie. Brìghde. Perth, Peairt. -

Brothers Report No 1/2007

Report on the investigation of the grounding of fv Brothers with the loss of two lives off Eilean Trodday on 1 June 2006 Marine Accident Investigation Branch Carlton House Carlton Place Southampton United Kingdom SO15 2DZ Report No 1/2007 January 2007 Extract from The United Kingdom Merchant Shipping (Accident Reporting and Investigation) Regulations 2005 – Regulation 5: “The sole objective of the investigation of an accident under the Merchant Shipping (Accident Reporting and Investigation) Regulations 2005 shall be the prevention of future accidents through the ascertainment of its causes and circumstances. It shall not be the purpose of an investigation to determine liability nor, except so far as is necessary to achieve its objective, to apportion blame.” NOTE This report is not written with litigation in mind and, pursuant to Regulation 13(9) of the Merchant Shipping (Accident Reporting and Investigation) Regulations 2005, shall be inadmissible in any judicial proceedings whose purpose, or one of whose purposes is to attribute or apportion liability or blame. Further printed copies can be obtained via our postal address, or alternatively by: Email: [email protected] Tel: 023 8039 5500 Fax: 023 8023 2459 All reports can also be found at our website: www.maib.gov.uk CONTENTS Page GLOSSARY OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS SYNOPSIS 1 SECTION 1 - FACTUAL INFORMATION 3 1.1 Particulars of Brothers and the accident 3 1.2 Background information 4 1.3 Narrative 4 1.4 Environmental conditions 10 1.5 Description of the boat and her equipment 10 -

2016 Scottish Vice-County Reports Dumfriesshire (Vc72) Chris Miles

2016 Scottish Vice-County Reports Dumfriesshire (vc72) Chris Miles Good progress was made with Atlas 2020 with 4732 records gathered from 25 monads and 18 tetrads. In the latest recording period, of the hectads with over 200 species recorded (range from 268-703), 20 have more than 70% of the species re-recorded. Of the 18 with less than 70% only 3 of these are less than 60%. These 18 will be the priority for recording in the three remaining seasons with the aim of getting as many hectads as possible above 70%. A field meeting in the Moffat Hills on 23/24 July was attended by 8 people. Some of the specialities found in new sites are highlighted in the field meeting report. Some good sites were found or revisited included a valley mire with calcareous flushes, unusual for Dumfriesshire, supporting Carex diandra (Lesser Tussock-sedge), Dactylorhiza incarnata subsp. incarnata (Early Marsh–orchid), Eriophorum latifolium (Broad-leaved Cottongrass), and Utricularia minor (Lesser Bladderwort). The refind of the small population of Persicaria vivipara (Alpine Bistort) in the ravine at Dalveen was the first record here since 1984. I finished the Rare Plant Register for Dumfriesshire which was published on the BSBI web pages in July. I made two recording visits to a square for the National Plant Monitoring Scheme and volunteered to be mentor for this scheme. I attended the Edinburgh and Shrewsbury recorders’ meetings and I volunteered to help develop recommendations for the BSBI review attending a residential weekend in January 2017. Kirkcudbrightshire (vc73) David Hawker 5000 records for 2016 from 62 monads were entered to the MM database with 10 NCRs, mostly casuals/aliens, except possibly for Imperatorium obstruthium (Masterwort); plus the 2nd records of Carex strigosa (Thin-stalked Wood-sedge) last seen in 1976 and Foeniculum officinale (Fennel). -

Marine Licence Authorising

MARINE SCOTLAND ACT 2010, PART 4 MARINE LICENSING LICENCE TO DEPOSIT ANY SUBSTANCE OR OBJECT IN THE SCOTTISH MARINE AREA Licence Number: MS-00008482 The Scottish Ministers (hereinafter referred to as "the Licensing Authority") hereby grant a marine licence authorising: Organic Sea Harvest Ltd MacDonald House Somerled Square Portree Isle of Skye IV51 9EH to deposit any substance or object as described in Part 2. The licence is subject to the conditions set out, or referred to, in Part 3. The licence is valid from 02 September, 2020 until 01 September, 2026 Signed: ……………………………………………………….. Anni Mäkelä For and on behalf of the Licensing Authority Date of issue 02 September, 2020 MS-00008482 2 September, 2020 1. PART 1 - GENERAL 1.1 Interpretation In the licence, terms are as defined in Section 1, 64 and 157 of the Marine Scotland Act 2010, and a) "the 2010 Act" means the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010; b) "Licensed Activity" means any activity or activities listed in section 21 of the 2010 Act which is, or are authorised under the licence; c) "Licensee" means Organic Sea Harvest Ltd d) "Mean high water springs" means any area submerged at mean high water spring tide; e) "Commencement of the Licensed Activity" means the date on which the first vehicle or vessel arrives on the site to begin carrying on any activities in connection with the Licensed Activity; f) "Completion of the Licensed Activity" means the date on which the Licensed Activity has been installed in full, or the Licensed Activity has been deemed complete by the Licensing Authority, whichever occurs first; All geographical co-ordinates contained within the licence are in WGS84 format (latitude and longitude degrees and minutes to three decimal places) unless otherwise stated. -

Cottage at Seadrift

Cottage at Seadrift Cottage at Seadrift Contact Details: Daytime Phone: 0*1+244 305162839405 S*t+affin0 T*h+e Hig0h1l2a3n4d5s6 I*V+51 9J0S1 Scotland £ 249.00 - £ 1,292.00 per week This delightful detached cottage sits in a superb location in the village of Staffin, sleeping two people in one bedroom. Facilities: Room Details: COVID-19: Sleeps: 2 Advance booking essential, Capacity limit, COVID-19 measures in place, COVID-19 refund and cancellation policy in place, 1 Bedroom COVID-19 risk assessment completed, Deep cleaning between visitors, Pets welcome during COVID-19 restrictions 1 Bathroom Communications: Broadband Internet Entertainment: TV Kitchen: Cooker, Fridge Laundry: Washing Machine Price Included: Linen, Towels About Staffin and The Highlands © 2021 LovetoEscape.com - Brochure created: 1 October 2021 Cottage at Seadrift About Staffin and The Highlands Occupying a coastal location on the northern half of the Isle of Skye, is the crofting village of Staffin. Overlooking Staffin Bay and Staffin Island, this tranquil village boasts something for everyone, with the Staffin Slipway for sailing enthusiasts, the only sandy beach in the north of Skye and plentiful walks along the beach or inland. © 2021 LovetoEscape.com - Brochure created: 1 October 2021 Cottage at Seadrift Recommended Attractions 1. Paultons Park Theme Parks Paultons Family Theme Park is a great day out, there are a wide The New Forest, SO51 6AL, Hampshire, selection of rides allowing you to have the must fun and exciting day England out. 2. Dunrobin Castle Golspie Sutherland Historic Buildings and Monuments, Visitor Centres and Museums Seat of the Duke of Sutherland. -

Scottish Birds Published by the SCOTTISH ORNITHOLOGISTS’ CLUB

*SB 29(2) COV AW 10/9/09 23:01 Page 1 SCOTTISH SCOTTISH Incorporating ScottishBirding Bird NewsScotland BIRDS and Volume 29 (2) 29 (2) Volume September 2009 Scottish Birds published by the SCOTTISH ORNITHOLOGISTS’ CLUB V OLUME 29(2) SEPTEMBER 2009 *SB 29(2) COV AW 10/9/09 23:01 Page 2 The Scottish Ornithologists’ Club (SOC) was formed in 1936 to Advice to contributors of main papers Scottish encourage all aspects of ornithology in Scotland. It has local Authors should bear in mind that only a small proportion of the branches which meet in Aberdeen, Ayr, the Borders, Dumfries, Scottish Birds readership are scientists and should aim to present Birds Dundee, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Inverness, New Galloway, Orkney, their material concisely, interestingly and clearly. Unfamiliar St Andrews, Stirling, Stranraer and Thurso, each with its own technical terms and symbols should be avoided wherever possible Originally established in 1958, programme of field meetings and winter lectures. The George incorporating Scottish Bird News and, if deemed essential, should be explained. Supporting statistics and Birding Scotland Waterston Library at the Club’s headquarters is the most should be kept to a minimum. All papers and short notes are comprehensive ornithological library in Scotland and is accepted on the understanding that they have not been offered for available for reference seven days a week. A selection of publication elsewhere and that they will be subject to editing. Published quarterly by: Scottish local bird reports is held at headquarters and may be Papers will be acknowledged on receipt and are normally reviewed The Scottish Ornithologists’ Club, purchased by mail order.