Problems of Survival : Role of the Co-Operative Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dr. Mahuya Hom Choudhury Scientist-C

Dr. Mahuya Hom Choudhury Scientist-C Patent Information Centre-Kolkata . The first State level facility in India to provide Patent related service was set up in Kolkata in collaboration with PFC-TIFAC, DST-GoI . Inaugurated in September 1997 . PIC-Kolkata stepped in the 4th plan period during 2012-13. “Patent system added the fuel to the fire of genius”-Abrham Lincoln Our Objective Nurture Invention Grass Root Innovation Patent Search Services A geographical indication is a sign used on goods that have a specific geographical origin and possess qualities or a reputation that are due to that place of origin. Three G.I Certificate received G.I-111, Lakshmanbhog G.I-112, Khirsapati (Himsagar) G.I 113 ( Fazli) G.I Textile project at a glance Patent Information Centre Winding Weaving G.I Certificate received Glimpses of Santipore Saree Baluchari and Dhanekhali Registered in G.I registrar Registered G.I Certificates Baluchari G.I -173-Baluchari Dhanekhali G.I -173-Dhaniakhali Facilitate Filing of Joynagar Moa (G.I-381) Filed 5 G.I . Bardhaman Mihidana . Bardhaman Sitabhog . Banglar Rasogolla . Gobindabhog Rice . Tulaipanji Rice Badshah Bhog Nadia District South 24 Parganas Dudheswar District South 24 Chamormoni ParganasDistrict South 24 Kanakchur ParganasDistrict Radhunipagol Hooghly District Kalma Hooghly District Kerela Sundari Purulia District Kalonunia Jalpaiguri District FOOD PRODUCTS Food Rasogolla All over West Bengal Sarpuria ( Krishnanagar, Nadia Sweet) District. Sarbhaja Krishnanagar, Nadia (Sweet) District Nalen gur All over West Bengal Sandesh Bardhaman Mihidana Bardhaman &Sitabhog 1 Handicraft Krishnanagar, Nadia Clay doll Dist. Panchmura, Bishnupur, Terrakota Bankura Dist. Chorida, Baghmundi 2 Chhow Musk Purulia Dist. -

Economics of Jamdani Handloom Product of Phulia in Nadia District of West Bengal

Vidyasagar University Journal of Economics, Vol. XVI, 2011-12 ISSN – 0975-8003 Economics of Jamdani Handloom Product of Phulia in Nadia District of West Bengal Chittaranjan Das* Assistant Professor of Commerce, V.S. Mahavidyalaya, Manikpara, Paschim Medinipur, West Bengal Abstract Jamdani sharee manufacturing has a long tradition of repute and excellence as a handicraft. Being a labour intensive handloom product it is produced with small amount of capital with substantial value addition. The present study seeks to examine the economics of Jamdani handloom product and labour process of production of jamdini cotton handloom product. Both gross profitability and net profitability in this industry are substantial for the independent units while gross income generated for the artisans working under different production organization is significant for livelihood. Variation in profitability across independent units and tied units is significantly explained by both labour productivity and capital productivity while that in units under cooperatives by capital productivity alone. For the industrial units taken together (60 units) across the three production organizations the profitability variation is explained by labour productivity, capital productivity and type of production organization. Production organization emerges as more significant than either labour productivity and capital productivity to explain the variation in profitability across the industrial units working under different production organizations. Keywords: employment, handloom, gross profitability, labour productivity, production organization. 1. Introduction Handloom is one of the oldest cottage industries in West Bengal and from the past it is a key element of state’s economy. The Handloom Census of 1987-88 indicated West Bengal population of handloom weavers at 1246005, with 3,38,499 looms. -

A Case Study in Nadia District of West Bengal

INTERNATIONALJOURNAL OF MULTIDISCIPLINARYEDUCATIONALRESEARCH ISSN:2277-7881; IMPACT FACTOR :6.514(2020); IC VALUE:5.16; ISI VALUE:2.286 Peer Reviewed and Refereed Journal: VOLUME:10, ISSUE:1(6), January :2021 Online Copy Available: www.ijmer.in IMPACT OF REFUGEE: A CASE STUDY IN NADIA DISTRICT OF WEST BENGAL Alok Kumar Biswas Assistant Professor, Department of History Vivekananda College, Madhyamgram, Kolkata Nadia or ‘Naudia’ is famous for its literature, cultural heritage, and historical importance and after all partition and change its demographic features. Brahmin Pandits were associated with intellectual literature discuss knowledge, to do religious oblation and worship. The city was fully surrounded by dense bamboo and marsh forest and tigers, wild pigs, foxes etc used live in this forest. This was the picture of Nadia during the end of 18th century.i There was a well-known rhyme- “Bamboo, box and pond, three beauties of Nadia”. Here ‘Nad’ means Nadia or Nabadwip.ii This district was established in 1786. During the partition, Nadia district was also divided. However, according to Lord Mountbatten’s plan 1947 during partition of India the whole Nadia district was attached with earlier East Pakistan. This creates a lot of controversy. To solve this situation the responsibility was given to Sir Radcliff According to his decision three subdivisions of Nadia district (Kusthia, Meherpur and Chuadanga) got attached with East Pakistan on 18th August, naming Kusthia district and the remaining two sub-divisions (Krishnagar and Ranaghat) centered into India with the name Nabadwip earlier which is now called Nadia. While studying the history of self-governing rule of Ndai district one can see that six municipalities had been established long before independence. -

The Silk Handloom Industry in Nadia District of West Bengal : a Study on Its History, Performance & Current Problems

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Munich RePEc Personal Archive MPRA Munich Personal RePEc Archive The silk handloom industry in Nadia district of West Bengal : a study on its history, performance & current problems Chandan Roy Kaliyaganj College, West Bengal, India July 2017 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/80601/ MPRA Paper No. 80601, posted 9 August 2017 17:09 UTC THE SILK HANDLOOM INDUSTRY IN NADIA DISTRICT OF WEST BENGAL : A STUDY ON ITS HISTORY, PERFORMANCE & CURRENT PROBLEMS Dr. Chandan Roy Assistant Professor & Head,Department of Economics Kaliyaganj College West Bengal, India (Email Id: [email protected]) Abstract Handloom industry provides widest employment opportunities in West Bengal, where 5.8% of the households involved have been found to be silk handloom weavers, which bears a rich legacy. Shantipur and Phulia in Nadia district are the two major handloom concentrated areas in West Bengal. The main objective of this paper is to make a situational analysis of the handloom workers by focusing on the problems of the handloom weavers of Nadia district. The paper briefly elaborates the historical perspective of handloom clusters over this region at the backdrop of the then Bengal. It also analyzes the present crisis faced by the weavers of Phulia and Shantipur region of Nadia district. It makes a SWOT analysis of the handloom industry where strength, weakness, opportunity and threat of the handlooms sector has been analyzed. The paper recommends several measures like awareness campaign, financial literacy programme, SHG and consortium formation, common facility centre, dye house, market exposure to upgrade the present situation of the handloom industry. -

Final Population (Villages and Towns), Nadia, West Bengal

CENSUS 1971 WEST BENGAL FINAL POPULATION (VILLAGES AND TOWNS) NADIA DISTRICT DIRECTORATE .Of CENSUS OPERATIONS WEST BENGAL PREFACE The final population totals of 1971 down to the village level will be presented, along with other demographic data, in the District Census Handbooks. It will be some more months before we can publish the Handbooks for all the districts of the State. At the request of the Government of West Bengal, we are therefore bringing out this special publication in the hope that it will meet, at least partly, the immediate needs of administrators, planners and scholars. Bhaskar Ghose Director of Census Operations West Bengal CONTENTS Page NADl A DlSTR[CT 3 -24 Krishnagar Subdlvision 1 P.S. Karimpur 3 -4 2 P.S. Tehatta 5 3 P.S. Kaliganj 6 -7 4 P.S. Nakasipara 8-9 5 P.S. Chapra 10 6 P.S. Krishnaganj 11 7 P.S. Krishnagar 12 -13 8 P.S. Nabadwip 1-1 Ranaghat Subdivision 9 P.S. Santipur 15 16 10 P.S. Hanskhali 17 11 P.S. Ranaghat 18 -20 12 P.S. Chakdah 21- -22 13 P.S. Kalyani 23 14 P.S. Haringhata 24 2- J.L. Name of Village) Total Scheduled Scheduled J.L Name of Village/ Total Scheduled Scheduled No. Town[Ward Population Castes Tribes No. TownjWard Population Caste~ Tribes 2 3 4- 5 2 3 4 5 NADIA DISTRICT Krisllnagar Subdi'l'ision J P.S. Karimpur Dogachhi 8,971 39 51 Khanpur 1,030 2 Dhoradaha 3,771 451 52 Chandpur 858 3 Jaygnata 159 159 53 GobindapuT 168 70 4 Manoharpur 1,004 174 54 Chak Hatisala 432 5 AbhaYPuT 1,054 63 55 KathaJia 2,761 978 2 6 Karimpur 3,778 464 56 Nandanpur 697 326 7 Gabrudanga 2,308 309 57 Rautoati 797 -

A Case Study of Urban Growth Trends of Nadia District in West Bengal

© 2018 JETIR April 2018, Volume 5, Issue 4 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) A CASE STUDY OF URBAN GROWTH TRENDS OF NADIA DISTRICT IN WEST BENGAL RIZANUZZAMAN MOLLA Research Scholar, Department of Geography, Seacom Skills University, Kendradangal, Bolpur, Bhirbhum, West Bengal, Pin- 731236 Abstract: Urban growth means an increased rate of an urban population in towns or cities and they moved from a rural to an urban area. At present, more than 40% of the world’s population are urban dwellers because of the rapid growth of urbanization which is the traditional and oldest processes of change. Due to urban growth and some others causes, West Bengal is the 4th most populous state and has the 2nd position for a high density of population in India. In the present work, an attempt has been made to find out the urban growth trends from 1901 to 2011 of Nadia district in West Bengal and the study also examines sub-divisional towns and others town’s urban growth of the district, and the distribution of urban centers of the district. As per 2011 census report, the total population is 5167600 and having a density of 1316 per square kilometer which is much higher density than the state of West Bengal (1102 sq/km) and India (940 sq/km). Keywords: Urban Growth, Urbanization, Density, Urban Growth Trends. I. Introduction: From the earlier period, we see it that people like to move to urban area from the rural area, for their better lifestyle, working facilities, good communication etc. Urbanization is a continuous process to change our social structure, culture and many more and it’s nearly associated with modernization and industrialization. -

4845 Rajib Ghosh Samir Ghosh M Santipur Buincha K.B

Sl No Student Name Guardian Name Sex Circle School Name Class Type % Bank Branch Name IFSC Code Bank Account No. Amount (Rs.) 4845 RAJIB GHOSH SAMIR GHOSH M SANTIPUR BUINCHA K.B. NIM BUNIYADIVIDYA IV CP 70 UBI FULIA UTBI0FLAW86 1982010085199 2500.00 4846 AKASH PRAMANIK MADAN PRAMANIK M SANTIPUR SANTIPUR MUNICIPAL HIGH SCHOOL (PRY V CP 50 ALLAHABAD SANTIPUR ALLA0210803 50234593285 2500.00 4847 BRISTI BASU RAJU BASU F SANTIPUR KAZI NAZRUL VIDYAPITH V CP 90 SBI SANTIPUR SBIN0000176 34717881313 4500.00 4848 HRITIZ RANJAN SAHA PINAKI SAHA M SANTIPUR SANTIPUR MUNICIPAL HIGH SCHOOL (PRY III CP 90 SBI SANTIPUR SBIN0000176 34584504862 2500.00 4849 SUMIT KHAN SANJAY KHAN M SANTIPUR BATHNA DURLAVPARA MSK VI CP 90 ALLAHABAD SANTIPUR ALLA0210803 50247782074 2500.00 VIVEKANANDA NAGAR VIVEKANANDA 4850 SHUVADIP NAG PROVASH NAG M SANTIPUR VIII CP 60 SBI SANTIPUR SBIN0000176 34298332400 2500.00 HIGH 4851 SUDIPTA GHOSH DEBOBRATA GHOSH M SANTIPUR TANTUBAI SANGHA HIGH SCHOOL VI CP 80 UBI SANTIPUR UTBI0SAN222 0217010494052 2500.00 4852 SUDIP PAL DIPANKAR PAUL M SANTIPUR UMAPUR PRY. SCHOOL IV CP 50 SBI FULIA SBIN0002057 34395357651 2500.00 4853 DEBASIS MALLICK JITEN MALLICK M SANTIPUR CHANDRAPUR SSK I CP 75 CBI TAHERPUR CBIN0284925 3535140381 2500.00 4854 ARADHANA GHOSH GOLAK GHOSH F SANTIPUR BUINCHA JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL VIII CP 80 UBI FULIA UTBI0FLAW86 1982010085180 4500.00 4855 MALI DUTTA MADAN DUTTA F SANTIPUR DACCAPARA PRY SCHOOL II CP 90 ALLAHABAD SANTIPUR ALLA0211798 50375984733 4500.00 4856 NILI KHATUN SEIKH DWIN ISLAM F SANTIPUR BERPARA MUSHLIM GIRLS PRY. SCHOOL III CP 100 SBI SANTIPUR SBIN0000176 35643873168 4500.00 4857 SRIJANI SEN MADHUMITA SEN F SANTIPUR DURGAMONI SREE PATHSALA VII MD 90 SBI SANTIPUR SBIN0000176 34224617438 4500.00 4858 RUP KUMAR DAFADAR MD. -

Co-Operative Based Economic Development in Phulia

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 20, Issue 9, Ver. III (Sep. 2015), PP 133-139 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Co-Operative Based Economic Development in Phulia Chandan Das M.Phil Student of Jadavpur University Abstract: The Handloom Industry is the most ancient cottage industry in India. The Indian handloom fabrics have been known for times immemorial for their beauty, excellence in design, texture and durability. Bengal handloom industry contributes a sustainable share in glorious Indian handloom craft floor. The excellence of TANGAIL cotton and silk sarees with extra warp and weft designs and also TANGAIL-JAMDANI sarees on cotton and silk are well accepted all over India. The Cooperative Societies have a major role in the movement of revival and development of Tangail Industry in Phulia. Among them Tangail Tantujibi Unnyan Samabay Samity is one of the pioneers in playing role of development in all aspect and to spread the flame of “PHULIA- TANGAIL” all over the country and abroad. Key Words: Co operative Formation, Export & Import, Empowerment, Socio Economic Change I. Introduction Phulia is in Nadia district of West Bengal is famous firstly as the holy birth place of Krittibas- a great poet of Bengali epic Ramayana, secondly and at present famous for the great prosperity of Tangail Handloom Industry. Once the idea of co-operative organization was derived in 1844 at Rochdale, a textile centre of England by a group of weavers which was spread and accepted throughout the world as successful economic system of poor and middle class peoples. -

Village and Town Directory, Nadia, Part XII-A , Series-26, West Bengal

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES -26 \AfEST I;3ENGAL DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PART XII-A VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY NADIA DISTRICT DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS WEST BENGAL Price Rs. 30.00 PUBLISHED BY THE CONTROLLER GOVERNMENT PRINTING, WEST BENGAL AND PRINTED BY SARASWATY PRESS LTD.' 11 B.T. RoID, . CALCUTTA -700'056 CONTENTS Page No. 1. Foreword i-ii 2. Preface iii- iv 3. Acknowledgements v-vi 4. Important Statistics vii -viii 5. Analytical Note and Analysis of Data ix - xxvi Part A - Village and Town Directory 6. Section I - Village Directory Note explaining the Codes used·in the Village Directory 3 (1) Santipur C.D. Block 4-7 (i) Village Directory (2) Chakdah C.D. Block 8-15 (i) Village Directory (3) Hanskhali C.D. Block 16-19 (i) Village Directory (4) Ranaghat - I C.D. Block 20-23 (i) Village Directory (5) Ranaghat -II C.D. Block 24-29 (i) Village Directory (6) Haringhata C.D. Block (i) Village Directory (7) Kaliganj C.D. Block 34-39 (i) Village Directory (8) I Krishnaganj C.D. Block 40-43 (i) Village Directory (9) Karimpur - I C.D. Block 44-51 (i) Village Directory (10) Karimpur -II C.D. Block 52-57 '(i) Village Directory (11) Nakashipara C.D. Block 58-63 -(i) Village Directory (12) Nabadwip C.D. Block 64-65 (i) Village Directory (13) Chapra C.D. Block 66-69 (i) Village Directory (14) Tehatta -I C.D. Block 70-75 (i) Village Directory (15) Tehatta -II C.D. Block 76-77 (i) Village Directory (16) Krishnagar -I C.D. -

SADAR DCRC 2021.Xlsx

Pickup plan for lifting of Polling Personnel from different pick up points to SADAR Krishnanagar Distribution Centre on P-1 day ie on 21.04.2021 Sl. Controling Departure No. of Bus will be reported Starting Point VIA Route Ending Point No. Block Time bus on P-2 Day at Krishnanagar Bus From BPC- Krishnanagar Govt 1 10 in every 15 mnt up to 10:00 AM - BDO Krishnagar -I Stand 07.00 am College Ground- CMS Krishnanagar I From BPC- Krishnanagar Govt 2 Krishnagar Rly Stn 10 in every 15 mnt up to 10:00 AM - BDO Krishnagar -I 07.00 am College Ground- CMS 7.30 A.M Mayapur Hulor Ghat - Mayapur - Bamanpurkur - Choegachha - Krishnanagar Govt. College 3 Mayapur Hulor Ghat 2 BDO Krishnagar -II 8.00 A.M PWD more - Himghar more - Pantirtha - BPC College Ground. Dhubulia BDO Office- Dhubulia Bus Stand - PWD more - Krishnanagar Govt. College 4Krishnagar-II Dhubulia Rly Stn 8.00 A.M 1 BDO Krishnagar -II Himghar more - Pantirtha - BPC College Ground. Bablari - Pirtala more - Nabadwip Bus stand - Nabadwip Rly. Stn. 7.30 A.M Krishnanagar Govt. College 5 Bablari bus stand 2 - Gournagar - Bishnupur - Nabadwip more - Panthatirtha - BPC BDO Nabadwip 7.45 A.M Ground. College From 7.00 A.M Nabadwip Rly Stn-Gournagar More - Bhaluka Bazar - Bhaluka Krishnanagar Govt College 6 Nabadwip Bus Stand in every 15 8 BDO Nabadwip more - Nabadwip more - Pantirtha - BPC College Ground. mnt up to 08:30 AM - Nabadwip 7.00 A.M Swarupganj Ghat - Fakirtala More -Maheshganj BDO Office - 7.15 A.M kishnagar Govt- College 7 Swarupganj Ghat 4 Road Station -Krishnanagar-I BDO Office - Nabadwip more - BDO Nabadwip 7.30 A.M Ground Pantirtha - BPC College 7.45 A.M Pickup plan for lifting of Polling Personnel from different pick up points to SADAR Krishnanagar Distribution Centre on P-1 day ie on 21.04.2021 Sl. -

RANAGHAT DCRC 2021.Xlsx

Pickup plan for lifting of Polling Personnel from different pick up points to Ranaghat Distribution Centre on P-1 day ie on 16.04.2021 Bus will be Sl. Controling Departure No. of Starting Point VIA Route Ending Point reported on P-2 Contact person Contact No. MV Department No. Block Time bus Day at Joy Nagar, Kagmari, Chitrasali Ranaghat 1 08.00 AM 1 Khamarsimulia, Badkulla, Taherpur' BDO Hanskhali Bazar College Birnagar, Ramnagar 08.20 AM Bagula Rly Station, Bagula Bus Stand 08.30 AM Hanskhali Chittashali, Khamar Shimulia, Ranaghat 2 08.40 AM 5 BDO Hanskhali Bazar Kadamtala Bus Stand,(Badkulla) College 08.50 AM Taherpur, Birnagar, Ramangar 09.00 AM Sridam Santra Bivash Barman 9434342936 7432923114 Hanskhali 07.30 AM Badkulla Railway Station, Badkulla, Ranaghat 3 Bapujinagar 07.45 AM 3 BDO Hanskhali Taherpur, Ramangar College 08.00 AM Hanskhali Bus Stand, Hanskhali 08.10 AM Bridge, Muragaccha, Bagula, Nona Hanskhali BDO Ranaghat 4 08.20 AM 3 Ganja More, Bagula Bus Stoppage, BDO Hanskhali Office College 08.30 AM College Stoppage, Tangrakhali, Bholamari, Datta Pulia, Pickup plan for lifting of Polling Personnel from different pick up points to Ranaghat Distribution Centre on P-1 day ie on 16.04.2021 Bus will be Sl. Controling Departure No. of Starting Point VIA Route Ending Point reported on P-2 Contact person Contact No. MV Department No. Block Time bus Day at 08.20 AM Ramnagar Milan Dutta Phulia Panikhali Dhantata Nokari, BDO Ranaghat- 5 08.40 AM 3 Bagan Siksha Bazar Rathtala, Ranaghat College II 09.00 AM Niketan Aranghata Rly Station, -

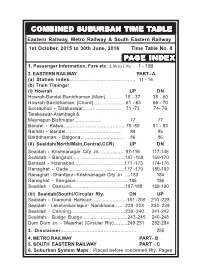

Combined Sub Combined Suburban Time Table Page

COMBINED SUBURBURBURBAN TIME TTTABLEABLEABLE Eastern Railway, Metro Railway & South Eastern Railway 1st October, 2015 to 30th June, 2016 Time Table No. 8 PPPAAAGE INDEX 1. Passenger Information, Fare etc. (E. Rly & S.E. Rly) 1 - 10B 2. EASTERN RAILWAY PART - A (a) Station Index............................................ 11 - 14 (b) Train Timings: (i) Howrah UP DN Howrah-Bandel-Barddhaman (Main)............ 15 - 37 38 - 60 Howrah-Barddhaman (Chord).......................61 - 65 66 - 70 Seoraphuli - Tarakeswar............................ 71 -73 74- 76 Tarakeswar-Arambagh & Maynapur-Bishnupur................... 77 77 Bandel - Katwa......................................... 78 -80 81 - 83 Naihati - Bandel...................................... 84 85 Barddhaman - Balgona.............................. 86 86 (ii) Sealdah(North/Main,Central,CCR) UP DN Sealdah - Krishnanagar City Jn.................. 87-116 117-146 Sealdah - Bangaon....................................147 -158 159-170 Barasat - Hasnabad..................................171 -173 174-176 Ranaghat - Gede......................................177 -179 180-182 Ranaghat - Shantipur- Krishnanagar City Jn .....183 184 Ranaghat - Bangaon....................................185 186 Sealdah - Dankuni.....................................187-188 189-190 (iii) Sealdah(South)/Circular Rly. DN UP Sealdah - Diamond Harbour.........................191 -209 210 -228 Sealdah - Lakshmikantapur- Namkhana........229 -233 234- 238 Sealdah - Canning.....................................239 -240 241-242 Sealdah