Aerosafety World, October 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MYRTLE BEACH AREA FAST FACTS the Myrtle Beach Area, Popularly

MYRTLE BEACH AREA FAST FACTS The Myrtle Beach area, popularly known as the Grand Strand, stretches from Little River to Pawleys Island, and is comprised of 14 communities along the South Carolina coast. Home to world-class golf, 60 miles of sandy beaches, exciting entertainment, family attractions and Southern hospitality and world-class golf, the Myrtle Beach area presents the quintessential vacation experience welcoming over 19 million visitors annually. LOCATION The Myrtle Beach area is the jewel of South Carolina and is nestled along the mid-Atlantic region of the eastern United States. WEATHER The Myrtle Beach area enjoys a mild annual average temperature of 73 F with an average of 215 sunny days each year. ○ POPULATION Approximately 298,000 people reside in the Grand Strand. LODGING There are approximately 425 hotels and 98,600 accommodation units in the Myrtle Beach area. From elegant golf and seaside resorts, to rustic cottages, bed & breakfasts and mom- and-pop motels, the Myrtle Beach area offers accommodations for every taste and appeals to every type of traveler. There are also several campgrounds located between Myrtle Beach and the South Strand, many of which are oceanfront or just steps away from the beach. In addition, there are a number of beach homes and condos available for rent, thereby giving vacationing families a true home away from home. DINING There are approximately 1,800 full-service restaurants in the Myrtle Beach area, and it’s no surprise that seafood is one of the primary cuisines. Murrells Inlet is nicknamed “the seafood capital of South Carolina” and Calabash-style restaurants are popular in the Northern Strand as well as Carolina/Lowcountry cuisine. -

Chapter 8: Transportation - 1 Unincorporated Horry County

INTRODUCTION Transportation plays a critical role in people’s daily routine and representation from each of the three counties, municipalities, addresses a minimum of a 20-year planning horizon and includes quality of life. It also plays a significant role in economic COAST RTA, SCDOT, and WRCOG. GSATS agencies analyze the both long- and short-range strategies and actions that lead to the development and public safety. Because transportation projects short- and long-range transportation needs of the region and offer development of an integrated, intermodal transportation system often involve local, state, and often federal coordination for a public forum for transportation decision making. that facilitates the efficient movement of people and goods. The funding, construction standards, and to meet regulatory Transportation Improvement Plan (TIP) is a 5 year capital projects guidelines, projects are identified many years and sometimes plan adopted by the GSATS and by SCDOT. The local TIP also decades prior to the actual construction of a new facility or includes a 3 year estimate of transit capital and maintenance improvement. Coordinating transportation projects with future requirements. The projects within the TIP are derived from the MTP. growth is a necessity. The Waccamaw Regional Council of Governments (WRCOG) not The Transportation Element provides an analysis of transportation only assists in managing GSATS, but it also helps SCDOT with systems serving Horry County including existing roads, planned or transportation planning outside of the boundaries of the MPO for proposed major road improvements and new road construction, Horry, Georgetown, and Williamsburg counties. SCDOT partnered existing transit projects, existing and proposed bicycle and with WRCOG to develop the Rural Long-Range Transportation Plan pedestrian facilities. -

02.26.18 Economic Impact Study Press Release

Kirk Lovell | Horry County Department of Airports 843.353.1431 | [email protected] IMMEDIATE RELEASE Horry County Department of Airports Horry County Airports Annual Economic Impact Exceeds $3B Myrtle Beach, SC, February 26, 2018 – The Horry County airport system’s total economic impact exceeds $3 billion annually. Horry County owns and operates the Myrtle Beach International Airport (MYR), Grand Strand Airport (CRE) Conway-Horry County (HYW) and Twin City Airport (5J9). Today the South Carolina Aeronautics Commission (SCAC) released its Statewide Aviation System Plan and Economic Impact Study. The comprehensive plan reports that the Horry County airport system supports 26,240 jobs, generates $3,025,501,000 in annual economic activity while contributing $122,088,040 in annual tax revenue to the region. Total Total Annual Total Annual Total Annual Total Annual Tax Employment Payroll Spending Economic Activity Revenue Myrtle Beach International Airport (MYR) 25,781 $778,878,690 $2,193,821,310 $2,972,700,000 $119,872,710 Conway-Horry County Airport (HYW) 72 $3,239,860 $5,856,660 $9,096,520 $382,660 Grand Strand Airport (CRE) 385 $12,334,580 $31,173,930 $43,508,510 $1,824,820 Loris Twin City Airport (5J9) 2 $70,450 $125,520 $195,970 $7,850 Total 26,240 $794,523,580 $2,230,977,420 $3,025,501,000 $122,088,040 “Aviation is important to any economy” said Scott Van Moppes, director of airports. “Horry County Department of Airports operates the airport system without the use of local tax dollars. The team proactively manages our airport system in a safe and efficient manner while striving to exceed the customers’ expectations. -

12–31–09 Vol. 74 No. 250 Thursday Dec. 31, 2009 Pages

12–31–09 Thursday Vol. 74 No. 250 Dec. 31, 2009 Pages 69243–69676 VerDate Nov 24 2008 18:44 Dec 30, 2009 Jkt 220001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4710 Sfmt 4710 E:\FR\FM\31DEWS.LOC 31DEWS hsrobinson on DSK69SOYB1PROD with PROPOSALS6 II Federal Register / Vol. 74, No. 250 / Thursday, December 31, 2009 The FEDERAL REGISTER (ISSN 0097–6326) is published daily, SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES Monday through Friday, except official holidays, by the Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records PUBLIC Administration, Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Register Subscriptions: Act (44 U.S.C. Ch. 15) and the regulations of the Administrative Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Committee of the Federal Register (1 CFR Ch. I). The Assistance with public subscriptions 202–512–1806 Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 is the exclusive distributor of the official General online information 202–512–1530; 1–888–293–6498 edition. Periodicals postage is paid at Washington, DC. Single copies/back copies: The FEDERAL REGISTER provides a uniform system for making Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Assistance with public single copies 1–866–512–1800 Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and (Toll-Free) Executive Orders, Federal agency documents having general FEDERAL AGENCIES applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published by act of Congress, and other Federal agency documents of public Subscriptions: interest. Paper or fiche 202–741–6005 Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Assistance with Federal agency subscriptions 202–741–6005 Federal Register the day before they are published, unless the issuing agency requests earlier filing. -

SC EV Market Study

SC EV Market Study 1 South Carolina Electric Vehicle Market Study Introduction 4 Current Assessment 5 Trends and Future Outlook 12 Implementation 17 Infrastructure Development 17 Educational Campaign: Plug in SC 22 1 Background Palmetto Clean Fuels (PCF) is an initiative of the South Carolina Office of Regulatory Staff - Energy Office (Energy Office). PCF is one of more than 100 U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Clean Cities designees and represents the entire state of South Carolina. Clean Cities is a locally based, voluntary public/private partnership created to promote energy use in the transportation sector that is clean, safe, sustainable, and less dependent upon foreign energy sources. Clean Cities builds on local initiatives and partnerships as well as nationwide networks to achieve its goals. By combining local decision- making with voluntary action by partners, this grassroots community action group seeks to create effective programs that support a sustainable nationwide alternative fuels market. PCF works to increase the use of alternative fuels and advanced vehicle technologies and strives to help public and private entities— as well as individuals— lower fuel costs, improve air quality, and reduce petroleum consumption. PCF also promotes idle reduction, fuel economy measures, vehicle miles traveled reductions, and bicycle and pedestrian efforts. 1 2 Introduction This study focuses on one aspect of PCF work—electric vehicles (EV). It builds on several regional studies as well as the past efforts of the organization, Plug-In Carolina. Plug-In Carolina, a registered non-profit, was selected to manage a program to install Electric Vehicle Supply Equipment (EVSE) funded with the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) through the Energy Office. -

Oceana Privileges Participating Businesses

Oceana Privileges Participating Businesses Business Location Phone Website Category Offer 1105 Hwy 17 S, North Myrtle 25% Off Bowling and Shoe Rentals, 15% Food and Non-Alcoholic Beverages. 710 Burgers, Bocce, Beer & Bowling 843.663.2695 710Bowling.com Attractions Beach Discount not valid on alcohol. Big M Casino 4491 Waterfront Drive, Little River 877.250.LUCK BigMCasino.com Attractions Show your Guest Privileges Card and boarding fees are waived. Brookgreen Gardens 1931 Brookgreen Dr, Murrells Inlet 843.235.6000 Brookgreen.org Attractions $2 Off Adult Admission 2 Show Package: Purchase tickets to The Carolina Opry and add tickets to Good The Carolina Opry 8901 N Kings Hwy, Myrtle Beach 843.913.4000 TheCarolinaOpry.com Attractions Vibrations for as low as $15 + tax. Same party must attend both shows within 10 days. Does not apply to platinum seating. Price does not include tax. Carolina Safari Jeep Tours Myrtle Beach - Call For Pickup CarolinaSafari.com Attractions $5 Off Per Couple’s Admission 2204 North Oak Street, Myrtle Children’s Museum of South Carolina 843.946.9469 CMSCKids.org Attractions 10% Off General Admission; Valid for the entire family! Beach 1903 Hwy 17 S, North Myrtle Coastal Scuba 843.361.3323 CoastalScuba.com Attractions $10 Off Discover Scuba Beach 1808 21st Avenue North, Myrtle $2.00 Off All Access Pass. Limit six discounts per coupon. Not Valid with another Hollywood Wax Museum 843.444.0091 HollywoodWaxMyrtleBeach.com Attractions Beach offer. Expires 12/31/2015. North Myrtle Beach Park and Jet Pack Adventures Sports -

Step Down Guide

Catch the Rising Tide Welcome Myrtle Beach, South Carolina is a world- class business destination and is poised to become a global hub for opportunity. Horry County offers a diverse mix of sites and buildings from Class A-certified industrial parks to business and commerce centers. Opportunities for businesses to thrive stem from a modern infrastructure, skilled workforce, and access to higher education. The expansion of the Myrtle Beach International Airport enables more fluid access to the 75 percent of the U.S. population that is found within a 1,000-mile radius, while access to I-95 via US 501 enables rapid product distribution. If you are just getting started, growing your business, relocating or opening a new facility, the Myrtle Beach area provides the ideal location for your success. ABOUT MBREDC Myrtle Beach Regional Economic Development Corporation (MBREDC) leads Horry County’s efforts to attract, retain, and grow sustainable businesses that create jobs. Horry County is one of South Carolina’s fastest growing counties and presents itself as a prime business location. To assist business development, MBREDC is a key resource for location and expansion assistance and development programs. Instrumental to economic growth, MBREDC unites key parties in the public and private sectors and diversifies the economy by attracting suitable and sustainable industries. MBREDC is supported by over 200 member businesses who are committed to economic growth in the region. 2050 Hwy 501 East, Building 100, Conway, South Carolina, 29526 Local: 843-347-4604 Toll Free: 1-800-844-4983 MBREDC.org 1 WORKFORCE South Carolina’s workforce is touted as one of the most productive in the country. -

Comprehensive Plan

HORRY COUNTY, South Carolina COMPREHENSIVE PLAN April 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS_____________________________________________ II TABLE OF GRAPHS, MAPS, PICTURES AND TABLES __________________ IX ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ___________________________________________ 1 INTRODUCTION __________________________________________________ 2 Reevaluating and Updating of the Envision 2025 Comprehensive Plan...................4 THE COMPREHENSIVE PLANNING PROCESS ........................................................4 Initial Community Outreach.......................................................................................4 ENVISION 2025 COMPREHENSIVE PLAN UPDATE – 2007 COMMUNITY INPUT MEETINGS ...................................................................................................................5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ____________________________________________ 7 POPULATION ELEMENT ___________________________________________ 12 POPULATION GROWTH............................................................................................12 POPULATION PROJECTIONS ..................................................................................14 SEASONAL POPULATION.........................................................................................15 POPULATION COMPOSITION ..................................................................................16 RACE AND ETHNICITY..............................................................................................16 AGE.............................................................................................................................16 -

Duke Radiology Beach Course

30TH ANNUAL Duke Radiology Beach Course July 26–30, 2021 Myrtle Beach, SC Updated Curriculum – Restructured, Multidisciplinary Approach Earn 21.75 hours AMA PRA Category 1 CreditsTM and 20 hours SA-CME Credit A Hilton and Embassy Suites Resort MYRTLE BEACH, SOUTH CAROLINA The Grand Strand: The Myrtle Beach “Grand Strand” has been called the “Seaside Golf Capital of the World” with over 100 area golf courses. Something for Everyone: The Myrtle Beach “Grand Strand” has activities for the entire family. Golf, fishing, scuba diving, parasailing, tennis, swimming, and biking are just some of the many activities available and within easy access during your visit. Whether relaxing at one of the areas premier spas, visiting local historical sites, shopping the outlets, or just soaking up the sun on our 60 miles of beautiful beaches, there is something for everyone at Myrtle Beach. The Kingston Plantation Featuring Embassy Suites: Wooded hills surround a twenty-acre freshwater lake and line the winding drive that leads to a half mile stretch of white sand beach. The twenty story, all-suite hotel provides a spectacular view of the ocean from each private balcony. Two and three bedroom luxury oceanfront condo- miniums or one, two and three bedroom villas set among the forest and lakes provide the ultimate in comfort and amenities during your stay. Kingston Plantation features the Sport and Health Club which includes nine lighted tennis courts, three racquetball and squash courts, indoor/outdoor pools, whirlpool, weight training equipment, free weights, an aerobics studio, tanning salon, cafe, and lounge. The hotel also has a full-time Golf Director affiliated with over 100 area courses. -

Layout 1 (Page 1)

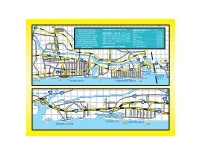

544 Carolina Forest Blvd GEORGETOWN COUNTY - 843-545-3213 Tanger Outlet The S.C. Department of EMERGENCY NUMBERS (Police) (843) Transportation Incident Atlantic Beach . 248-1520 Response Unit assists HORRY COUNTY - Dial *HP - The Horry Aynor . 358-3900 County area served is S.C. 31 from S.C. Forestbrook Rd motorists with minor repairs Conway. 248-1790 544 to S.C. 22, U.S. 501 from Myrtle Horry County . 915-5350 to disabled vehicles, assists Beach to Conway: the U.S. 17 Bypass; with traffic control and and S.C. 905. For help dial *HP on your Loris . 756-4001 incident management and cellular phone and ask for S.C. DOT Myrtle Beach . 918-1382 George Bishop Pkwy River Oaks Dr when needed, provides first Incident Response North Myrtle Beach. 280-5511 aid until emergency medical Surfside Beach. 913-6368 services arrive. BRUNSWICK COUNTY - 910-259-4919 S.C. Highway Patrol . 365-5001 Socastee Blvd. Socastee 501 Hwy. 57 Farrow Coastal Grand Mall Harrelson Blvd 9 Parkw BYPASS 90 Seaboard St Broadway 31 Watertower Rd. LITTLE TO SUNSET BEACH ay 17 at the Beach AND OCEAN ISLE Robert Grissom Parkway Grand Dunes RIVER 82nd Parkway Boulevard 10th Ave.N 21st Ave N 38th Ave N 62nd Ave N 76th Ave N 17 29th Ave N 48th Ave N 67th Ave N 79th Ave N NORTH CAROLINA 22 SOUTH CAROLINA Mineola Ave. Highway 15 Baldwin Ave. Possum Robert Edge Pkwy 904 Myrtle 179 Lake Arrowhead Lake Rd Trot Rd Beach Barefoot Mall Sea Mountain Hwy Oak Chestnut Rd Landing Grand Strand Airport 17 CALABASH Myrtle Beach BUSINESS Tanger International Outlet 11th Ave N The Market Little River -

Faces of the Grand Strand

Myrtle Beach Area Fast Facts The Myrtle Beach area, popularly known as the Grand Strand, stretches from Little River to Pawleys Island, and is comprised of 12 communities along the South Carolina coast. Home to world-class golf, 60 miles of sandy beaches, exciting entertainment, family attractions and Southern hospitality, the Myrtle Beach area presents the quintessential vacation experience welcoming over 17.2 million visitors annually. LOCATION The Myrtle Beach area is the jewel of South Carolina, nestled along the mid- Atlantic region of the eastern United States. WEATHER The Myrtle Beach area enjoys a mild annual average temperature of 74º F with an average of 215 sunny days each year. POPULATION There are approximately 298,000 residents in the Grand Strand. LODGING There are approximately 425 hotels and 98,600 accommodation units in the Myrtle Beach area. From elegant golf and seaside resorts, to rustic cottages, bed & breakfasts and mom-and-pop motels, the Myrtle Beach area offers accommodations for every taste and appeals to every type of traveler. There are also several campgrounds located between Myrtle Beach and the South Strand, many of which are oceanfront or just steps away from the beach. There are also a number of beach homes and condos available for rent, thereby giving vacationing families a true home away from home. DINING There are approximately 1,800 full-service restaurants in the Myrtle Beach area and it’s no surprise that seafood is one of the primary cuisines. Murrells Inlet is nicknamed “the seafood capital of South Carolina” and Calabash-style restaurants are popular in the Northern Strand as well as Carolina Coastal Cuisine. -

Economic Impact Study Are Shown in Figure 1 – Study Airports

Contents 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 4 2.0 Sources & Measurements of Economic Impact for the 57 Public Airports in South Carolina ..................... 6 2.1 Sources for Airport Specific Economic Impacts ................................................................................................ 6 2.2 Measurements for Airport Specific Economic Impacts .................................................................................... 8 2.3 Method to Estimate Airport Specific Economic Impacts .................................................................................. 8 3.0 Direct Economic Impacts for Commercial and General Aviation Airports ................................................. 9 3.1 Estimates of Direct Impacts for Airport Management for Commercial Airports .............................................. 9 3.2 Estimates of Direct Impacts for Airport Tenants at Commercial Airports and Combined Airport Management and Tenant Impacts for General Aviation Airports .................................................................. 10 3.3 Estimates of Direct Impacts for Capital Investment ....................................................................................... 13 3.4 Estimates of Direct Impacts from Boeing Commercial Airplane Division ....................................................... 16 3.5 Estimates of Direct Impacts from General Aviation Visitors..........................................................................