SC EV Market Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

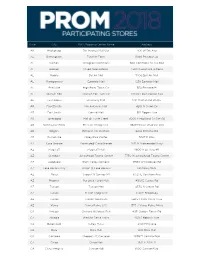

Prom 2018 Event Store List 1.17.18

State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address AK Anchorage 5th Avenue Mall-Sur 406 W 5th Ave AL Birmingham Tutwiler Farm 5060 Pinnacle Sq AL Dothan Wiregrass Commons 900 Commons Dr Ste 900 AL Hoover Riverchase Galleria 2300 Riverchase Galleria AL Mobile Bel Air Mall 3400 Bell Air Mall AL Montgomery Eastdale Mall 1236 Eastdale Mall AL Prattville High Point Town Ctr 550 Pinnacle Pl AL Spanish Fort Spanish Fort Twn Ctr 22500 Town Center Ave AL Tuscaloosa University Mall 1701 Macfarland Blvd E AR Fayetteville Nw Arkansas Mall 4201 N Shiloh Dr AR Fort Smith Central Mall 5111 Rogers Ave AR Jonesboro Mall @ Turtle Creek 3000 E Highland Dr Ste 516 AR North Little Rock Mc Cain Shopg Cntr 3929 Mccain Blvd Ste 500 AR Rogers Pinnacle Hlls Promde 2202 Bellview Rd AR Russellville Valley Park Center 3057 E Main AZ Casa Grande Promnde@ Casa Grande 1041 N Promenade Pkwy AZ Flagstaff Flagstaff Mall 4600 N Us Hwy 89 AZ Glendale Arrowhead Towne Center 7750 W Arrowhead Towne Center AZ Goodyear Palm Valley Cornerst 13333 W Mcdowell Rd AZ Lake Havasu City Shops @ Lake Havasu 5651 Hwy 95 N AZ Mesa Superst'N Springs Ml 6525 E Southern Ave AZ Phoenix Paradise Valley Mall 4510 E Cactus Rd AZ Tucson Tucson Mall 4530 N Oracle Rd AZ Tucson El Con Shpg Cntr 3501 E Broadway AZ Tucson Tucson Spectrum 5265 S Calle Santa Cruz AZ Yuma Yuma Palms S/C 1375 S Yuma Palms Pkwy CA Antioch Orchard @Slatten Rch 4951 Slatten Ranch Rd CA Arcadia Westfld Santa Anita 400 S Baldwin Ave CA Bakersfield Valley Plaza 2501 Ming Ave CA Brea Brea Mall 400 Brea Mall CA Carlsbad Shoppes At Carlsbad -

Q413 Supplemental 021814.Xlsx

Pennsylvania Real Estate Investment Trust ® Supplemental Financial and Operating Information Quarter Ended December 31, 2013 www.preit.com NYSE: PEI NYSE: PEIPRA, PEIPRB Pennsylvania Real Estate Investment Trust Supplemental Financial and Operating Information December 31, 2013 Table of Contents Introduction Company Information 1 Market Capitalization and Capital Resources 2 Operating Results Statement of Operations - Proportionate Consolidation Method - Quarters Ended December 31, 2013 and December 31, 2012 3 Statement of Operations - Proportionate Consolidation Method - Years Ended December 31, 2013 and December 31, 2012 4 Statement of Net Operating Income - Quarters and Years Ended December 31, 2013 and December 31, 2012 5 Computation of Earnings Per Share 6 Funds From Operations and Funds Available for Distribution - Quarters Ended December 31, 2013 and December 31, 2012 7 Funds From Operations and Funds Available for Distribution - Years Ended December 31, 2013 and December 31, 2012 8 Operating Statistics Leasing Activity Summary 9 Summarized Sales and Rent Per Square Foot and Occupancy Percentages 10 Mall Occupancy Percentage and Sales Per Square Foot 11 Strip and Power Center Occupancy Percentages 12 Top Twenty Tenants 13 Lease Expirations 14 Property Information 15 Department Store Lease Expirations 17 Balance Sheet Condensed Balance Sheet - Proportionate Consolidation Method 19 Investment in Real Estate 20 Capital Expenditures 22 Debt Analysis 23 Debt Schedule 24 Selected Debt Ratios 25 Definitions 26 Forward Looking Statements 27 Pennsylvania Real Estate Investment Trust Company Information Background Pennsylvania Real Estate Investment Trust, founded in 1960 and one of the first equity REITs in the U.S., has a primary investment focus on retail shopping malls. As of December 31, 2013, the Company owned interests in 43 retail properties, 40 of which are operating retail properties and three are development properties. -

MYRTLE BEACH AREA FAST FACTS the Myrtle Beach Area, Popularly

MYRTLE BEACH AREA FAST FACTS The Myrtle Beach area, popularly known as the Grand Strand, stretches from Little River to Pawleys Island, and is comprised of 14 communities along the South Carolina coast. Home to world-class golf, 60 miles of sandy beaches, exciting entertainment, family attractions and Southern hospitality and world-class golf, the Myrtle Beach area presents the quintessential vacation experience welcoming over 19 million visitors annually. LOCATION The Myrtle Beach area is the jewel of South Carolina and is nestled along the mid-Atlantic region of the eastern United States. WEATHER The Myrtle Beach area enjoys a mild annual average temperature of 73 F with an average of 215 sunny days each year. ○ POPULATION Approximately 298,000 people reside in the Grand Strand. LODGING There are approximately 425 hotels and 98,600 accommodation units in the Myrtle Beach area. From elegant golf and seaside resorts, to rustic cottages, bed & breakfasts and mom- and-pop motels, the Myrtle Beach area offers accommodations for every taste and appeals to every type of traveler. There are also several campgrounds located between Myrtle Beach and the South Strand, many of which are oceanfront or just steps away from the beach. In addition, there are a number of beach homes and condos available for rent, thereby giving vacationing families a true home away from home. DINING There are approximately 1,800 full-service restaurants in the Myrtle Beach area, and it’s no surprise that seafood is one of the primary cuisines. Murrells Inlet is nicknamed “the seafood capital of South Carolina” and Calabash-style restaurants are popular in the Northern Strand as well as Carolina/Lowcountry cuisine. -

Arkansas Colorado Florida Georgia Illinois Indiana

THE FOLLOWING STORES ARE CLOSED THANKSGIVING - RE-OPEN AT 5AM FRIDAY SHOP BLACK FRIDAY DOORBUSTERS ALL DAY THANKSGIVING AT SEARS.COM ALL OTHER SEARS STORES OPEN 6PM THANKSGIVING DAY ARKANSAS ILLINOIS NEW MEXICO HOT SPRINGS SEARS PERU SEARS BROADMOOR CENTER 4501 CENTRAL AVE STE 101 1607 36TH ST 1000 S MAIN ST HOT SPRINGS, AR PERU, IL, 61354-1232 ROSWELL, NM (501) 525-5197 M(815) 220-4700 (575) 622-1310 6P NORTH PLAINS MALL THANKSGIVINGCOLORADO INDIANA 2811 N PRINCE ST CLOVIS, NM FORT COLLINS SEARS MARQUETTE S/C (575) 769-4700 3400 S COLLEGE AVENUE 3901 FRANKLIN ST FT COLLINS, CO MICHIGAN CITY , IN 46360-7314 970-297-2770 (219) 878-6600 NEW YORK TOWN SQUARE SHOPPING CTR WILTON MALL FLORIDA 120 US HIGHWAY 41 3065 ROUTE 50 SCHERERVILLE, IN SARATOGA SPGS, NY GULF VIEW SQ (219) 864-8987 (518) 583-8500 9409 US HIGHWAY 19 N STE 101 PORT RICHEY, FL (727) 846-6255 MARYLAND NORTH CAROLINA OVIEDO MARKETPLACE EAST POINT MALL MONROE MALL 1360 OVIEDO MARKETPLACE BLVD 7885 EASTERN BLVD 2115 E ROOSEVELT BLVD STE 200 OVIEDO, FL BALTIMORE, MD MONROE, NC (407) 971-2600 (410) 288-7700 (704) 225-2100 SEMINOLE TOWNE CTR TOWNMALL OF WESTMINSTER RANDOLPH MALL 320 TOWNE CENTER CIR 400 N CENTER ST 200 RANDOLPH MALL SANFORD, FL WESTMINSTER, MD ASHEBORO, NC (407) 328-2600 (410) 386-6500 (336) 633-3200 SEARSTOWN MALL 3550 S WASHINGTON AVE MISSOURI NORTH DAKOTA TITUSVILLE, FL (321) 268-9255 EAST HILLS MALL COLUMBIA MALL 3702 FREDERICK AVE 2800 S COLUMBIA RD SAINT JOSEPH, MO GRAND FORKS, ND GEORGIA (816) 364-7000 (701) 787-9300 ALBANY MALL 2601 DAWSON RD BLDG G NEW -

TRANSPORTATION IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM Adopted by the GSATS Policy Committee Sept

GRAND STRAND AREA TRANSPORTATION STUDY TRANSPORTATION IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM Adopted by the GSATS Policy Committee Sept. 11, 2020 FISCAL YEAR 2020 TIP PERIOD: OCTOBER 1, 2019 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2028 FY 2020 OCTOBER 1. 2019 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2020 FY 2021 OCTOBER 1. 2020 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2021 FY 2022 OCTOBER 1. 2021 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2022 FY 2023 OCTOBER 1. 2022 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2023 FY 2024 OCTOBER 1. 2023 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2024 FY 2025 OCTOBER 1. 2024 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2025 FY 2026 OCTOBER 1. 2025 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2026 FY 2027 OCTOBER 1. 2026 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2027 FY 2028 OCTOBER 1. 2027 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2028 The GSATS has established performance management targets for highway safety, infrastructure condition, congestion, system reliability, emissions, freight movement and transit. The GSATS anticipates meeting their identified targets with the mix of projects included in the GY 2019 – 2028 TIP. 2019-2028 Transportation Improvement Program Grand Strand Area Transportation Study KEY ARRA................................................................American Reinvestment and Recovery Act CAP...................................................................Capital CONST..............................................................Construction FTA....................................................................Federal Transit Administration FY......................................................................Fiscal Year NHS...................................................................National Highway System OP......................................................................Operating -

Chapter 8: Transportation - 1 Unincorporated Horry County

INTRODUCTION Transportation plays a critical role in people’s daily routine and representation from each of the three counties, municipalities, addresses a minimum of a 20-year planning horizon and includes quality of life. It also plays a significant role in economic COAST RTA, SCDOT, and WRCOG. GSATS agencies analyze the both long- and short-range strategies and actions that lead to the development and public safety. Because transportation projects short- and long-range transportation needs of the region and offer development of an integrated, intermodal transportation system often involve local, state, and often federal coordination for a public forum for transportation decision making. that facilitates the efficient movement of people and goods. The funding, construction standards, and to meet regulatory Transportation Improvement Plan (TIP) is a 5 year capital projects guidelines, projects are identified many years and sometimes plan adopted by the GSATS and by SCDOT. The local TIP also decades prior to the actual construction of a new facility or includes a 3 year estimate of transit capital and maintenance improvement. Coordinating transportation projects with future requirements. The projects within the TIP are derived from the MTP. growth is a necessity. The Waccamaw Regional Council of Governments (WRCOG) not The Transportation Element provides an analysis of transportation only assists in managing GSATS, but it also helps SCDOT with systems serving Horry County including existing roads, planned or transportation planning outside of the boundaries of the MPO for proposed major road improvements and new road construction, Horry, Georgetown, and Williamsburg counties. SCDOT partnered existing transit projects, existing and proposed bicycle and with WRCOG to develop the Rural Long-Range Transportation Plan pedestrian facilities. -

Citadel Vs Clemson (9/16/1978)

Clemson University TigerPrints Football Programs Programs 1978 Citadel vs Clemson (9/16/1978) Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms Materials in this collection may be protected by copyright law (Title 17, U.S. code). Use of these materials beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. For additional rights information, please contact Kirstin O'Keefe (kokeefe [at] clemson [dot] edu) For additional information about the collections, please contact the Special Collections and Archives by phone at 864.656.3031 or via email at cuscl [at] clemson [dot] edu Recommended Citation University, Clemson, "Citadel vs Clemson (9/16/1978)" (1978). Football Programs. 131. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms/131 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Programs at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Football Programs by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OFFICIAL PROGRAM • MEMORIAL STADIUM • SEPTEMBER 16, 1978 vs THE CITADEL Eastern Distribution is people who know how to handle things People who can get anything at all from one place to another on the right timetable, and in perfect condition. Murphy MacLean, Vice President/Florida, and Sherry Herren, Vice President/S. C. Eastern Distribution Office Manager Dianne Moore, Sales Representative Sherry Turner, and Controller Carrol Garrett Yes, the Eastern people on Harold Segars' Greenville, S. C, and Jacksonville, Fla., distribution team get things done, whether they're arranging the same-day movement of something you want out in a hurry, or consolidating loads to save you money through lower rates. -

02.26.18 Economic Impact Study Press Release

Kirk Lovell | Horry County Department of Airports 843.353.1431 | [email protected] IMMEDIATE RELEASE Horry County Department of Airports Horry County Airports Annual Economic Impact Exceeds $3B Myrtle Beach, SC, February 26, 2018 – The Horry County airport system’s total economic impact exceeds $3 billion annually. Horry County owns and operates the Myrtle Beach International Airport (MYR), Grand Strand Airport (CRE) Conway-Horry County (HYW) and Twin City Airport (5J9). Today the South Carolina Aeronautics Commission (SCAC) released its Statewide Aviation System Plan and Economic Impact Study. The comprehensive plan reports that the Horry County airport system supports 26,240 jobs, generates $3,025,501,000 in annual economic activity while contributing $122,088,040 in annual tax revenue to the region. Total Total Annual Total Annual Total Annual Total Annual Tax Employment Payroll Spending Economic Activity Revenue Myrtle Beach International Airport (MYR) 25,781 $778,878,690 $2,193,821,310 $2,972,700,000 $119,872,710 Conway-Horry County Airport (HYW) 72 $3,239,860 $5,856,660 $9,096,520 $382,660 Grand Strand Airport (CRE) 385 $12,334,580 $31,173,930 $43,508,510 $1,824,820 Loris Twin City Airport (5J9) 2 $70,450 $125,520 $195,970 $7,850 Total 26,240 $794,523,580 $2,230,977,420 $3,025,501,000 $122,088,040 “Aviation is important to any economy” said Scott Van Moppes, director of airports. “Horry County Department of Airports operates the airport system without the use of local tax dollars. The team proactively manages our airport system in a safe and efficient manner while striving to exceed the customers’ expectations. -

CBL & Associates Properties 2012 Annual Report

COVER PROPERTIES : Left to Right/Top to Bottom MALL DEL NORTE, LAREDO, TX CROSS CREEK MALL, FAYETTEVILLE, NC BURNSVILLE CENTER, BURNSVILLE, MN OAK PARK MALL, KANSAS CITY, KS CBL & Associates Properties, Inc. 2012 Annual When investors, business partners, retailers Report CBL & ASSOCIATES PROPERTIES, INC. and shoppers think of CBL they think of the leading owner of market-dominant malls in CORPORATE OFFICE BOSTON REGIONAL OFFICE DALLAS REGIONAL OFFICE ST. LOUIS REGIONAL OFFICE the U.S. In 2012, CBL once again demon- CBL CENTER WATERMILL CENTER ATRIUM AT OFFICE CENTER 1200 CHESTERFIELD MALL THINK SUITE 500 SUITE 395 SUITE 750 CHESTERFIELD, MO 63017-4841 strated why it is thought of among the best 2030 HAMILTON PLACE BLVD. 800 SOUTH STREET 1320 GREENWAY DRIVE (636) 536-0581 THINK 2012 Annual Report CHATTANOOGA, TN 37421-6000 WALTHAM, MA 02453-1457 IRVING, TX 75038-2503 CBLCBL & &Associates Associates Properties Properties, 2012 Inc. Annual Report companies in the shopping center industry. (423) 855-0001 (781) 398-7100 (214) 596-1195 CBLPROPERTIES.COM HAMILTON PLACE, CHATTANOOGA, TN: Our strategy of owning the The 2012 CBL & Associates Properties, Inc. Annual Report saved the following resources by printing on paper containing dominant mall in SFI-00616 10% postconsumer recycled content. its market helps attract in-demand new retailers. At trees waste water energy solid waste greenhouse gases waterborne waste Hamilton Place 5 1,930 3,217,760 214 420 13 Mall, Chattanooga fully grown gallons million BTUs pounds pounds pounds shoppers enjoy the market’s only Forever 21. COVER PROPERTIES : Left to Right/Top to Bottom MALL DEL NORTE, LAREDO, TX CROSS CREEK MALL, FAYETTEVILLE, NC BURNSVILLE CENTER, BURNSVILLE, MN OAK PARK MALL, KANSAS CITY, KS CBL & Associates Properties, Inc. -

2Q17 Columbia Retail Market Report

2Q17: Columbia Retail Market Report Grocers In, Big Box Retailers Out VACANCY The Columbia retail market stayed steady between the close of 2016 and the close of the second quarter, with vacancy 5.3% creeping from 5.1% to 5.3%. Net absorption this quarter Rates crept upwards from 5.1% in 4Q16 was negative 18,174 square feet (SF), compared to a positive 306,581 SF at the close of the fourth quarter 2016. NAI Avant Director of Retail Services Patrick Palmer, CCIM attributes the negative net absorption to big box retailers NET ABSORPTION closing their doors, making more vacant space available in the market. For example, this quarter, HH Gregg closed its doors -18,174 SF and moved out of ±30,396 SF at Village at Sandhill Forum 306,581 SF in 4Q16 Center, in addition to vacating the chain’s ±69,023 SF location on Bower Parkway. But the Columbia retail market remains steady and strong. Average rental rates rose from $11.06 SF at the close of 2016, AVERAGE RENTAL RATE to $11.42 SF at the close of the second quarter 2017. The Central Business District continues to own the highest rental $11.42 rate at $19.38 SF. Up from $11.06 in 4Q16 The highlights for the Columbia retail market in the second quarter of 2017 center around major grocery store openings and announcements. VACANCY: MALLS Impact of E-Commerce: Columbia is no exception to the nationwide 13.6% reality of big box retailers closing their doors. The only building type that saw Nearly every major department store, including decreased vacancy in 2Q17 Macy’s, Kohl’s, Walmart, and Sears, have closed hundreds of stores due to the rise of e-commerce. -

The Highlands at Socastee (Myrtle Beach)

Market Feasibility Analysis The Highlands at Socastee State Route 707 Myrtle Beach, Horry County, South Carolina 29588 Prepared For Mr. Randy Aldridge Quad-State Development, Inc. 841 Sweetwater Avenue Florence, Alabama 35630 Effective Date January 26, 2016 Job Reference Number 15-525 JW 155 E. Columbus Street, Suite 220 Pickerington, Ohio 43147 Phone: (614) 833-9300 Bowennational.com TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Primary Market Area Analysis Summary (Exhibit S-2) B. Project Description C. Site Description and Evaluation D. Primary Market Area Delineation E. Market Area Economy F. Community Demographic Data G. Project-Specific Demand Analysis H. Rental Housing Analysis (Supply) I. Interviews J. Recommendations K. Signed Statement Requirement L. Qualifications M. Methodologies, Disclaimers & Sources Addendum A – Field Survey of Conventional Rentals Addendum B – NCHMA Member Certification & Checklist 10/19/15 2016 EXHIBIT S – 2 SCSHFDA PRIMARY MARKET AREA ANALYSIS SUMMARY: Development Name: The Highlands of Socastee Total # Units: 44 Location: State Route 707, Myrtle Beach, SC 29588 # LIHTC Units: 44 Socastee city limits, State Route 544 and State Route 31 to the north; Robert M. Grissom Parkway, Granddaddy Drive and Poinsett Road to the east; the Atlantic Ocean to the south; Spanish Oak Drive, PMA Boundary: Holmestown Road, State Route 707, Bay Road and the Waccamaw River to the west. Development Type: __X__Family ____Older Persons Farthest Boundary Distance to Subject: 10.0 miles RENTAL HOUSING STOCK (found on page H-1, 15 & 16) Type # Properties Total Units Vacant Units Average Occupancy All Rental Housing 21 3,469 165 95.2% Market-Rate Housing 12 2,669 165 93.8% Assisted/Subsidized Housing not to 2 152 0 100.0% include LIHTC LIHTC (All that are stabilized)* 9 648 0 100.0% Stabilized Comps** 6 416 0 100.0% Non-stabilized Comps 0 - - - * Stabilized occupancy of at least 93% (Excludes projects still in initial lease up). -

Bicentennial News

2 South Carolina BICENTENNIAL NEWS Volume 2 "Battleground of Freedom" Number 3 State Commission Approves Grants South Carolina's Bicentennial Commission has approved matching grants to seven Bicentennial pro jects in the state. The largest grants approved were $10,000 to the Orangeburg Bicenten nial Committee for the restoration of the Donald Bruce House and an other $10,000 grant to the Camden Historical Commission for archaeo logical excavations at the 1781 town site. The Donald Bruce House, con structed in 1735 and moved to Mid Highway Commissioner Silas Pearman (from left) Governor James B. Edwards, Former dlepen Plantation near Orangeburg Governor John C. West and SCARBC vice-chairman Sam Manning admire the new in 1835, would be moved closer to highway map. the city. Other grant requests approved in clude $2,500 to the Georgetown MAP FEATURES BICENTENNIAL County Bicentennial Committee for establishing a Bicentennial Munici South Carolina's role as the "Bat of the Ninety Six Fort, and a picture pal Park; $3,000 to the Fairfield tleground of Freedom" during the of "Marion Crossing the Pee Dee" County Historical Society for con American Revolution is dramatized appear on a reproduction of Mou sulting advice on furnishing and ex in the South Carolina Highway De zon's famous map of 1775. hibits for use in Winnsboro's Ketch partment's new 1975 primary system Fifty of the most important battles in Building; $1,500 to the South map. are described and their locations pin Carolina Federation of Music Clubs Chief Highway Commissioner Silas pointed on the modern-day primary that will be used to underwrite the Pearman and South Carolina Bicen system map.