'Inside Sports': a Framing Analysis of College Gameday

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Binge-Reviews? the Shifting Temporalities of Contemporary TV Criticism

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Communication & Theatre Arts Faculty Communication & Theatre Arts Publications 2016 Binge-Reviews? The hiS fting Temporalities of Contemporary TV Criticism Myles McNutt Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/communication_fac_pubs Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, and the Publishing Commons Repository Citation McNutt, Myles, "Binge-Reviews? The hiS fting Temporalities of Contemporary TV Criticism" (2016). Communication & Theatre Arts Faculty Publications. 15. https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/communication_fac_pubs/15 Original Publication Citation McNutt, M. (2016). Binge-Reviews? The hiS fting Temporalities of Contemporary TV Criticism. Film Criticism, 40(1), 1-4. doi: 10.3998/fc.13761232.0040.120 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication & Theatre Arts at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication & Theatre Arts Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FILM CRITICISM Binge-Reviews? The Shifting Temporalities of Contemporary TV Criticism Myles McNutt Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information) Volume 40, Issue 1, January 2016 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/fc.13761232.0040.120 Permissions When should television criticism happen? The answer used to be pretty simple for critics: reviews were published before a series premiered, with daily or -

Game Nine #2/2 Notre Dame (8-0, 7-0 Acc) at #25/23 North Carolina (6-2, 6-2 Acc)

GAME NINE #2/2 NOTRE DAME (8-0, 7-0 ACC) AT #25/23 NORTH CAROLINA (6-2, 6-2 ACC) THE COACHES GAME INFORMATION Head Coach At School Overall vs. Opponent Friday, November 27 Kenan Memorial Stadium ND Brian Kelly 100-37 (11th year)ˆ 271-94-2 (30th year)ˆ 2-0 3:30 p.m. ET Chapel Hill, NC Capacity 50,500 (Synthetic Grass) UNC Mack Brown 82-54-1 (12th year) 257-130-1 (32nd year) 0-0 ABC Chris Fowler (play-by-play) ˆ -Includes 20 regular-season wins and two postseason appearances vacated under discretionary NCAA penalty Kirk Herbstreit (analyst) BY THE NUMBERS Maria Taylor (reporter) QB Ian Book is 28-3 (.903) as a starter, making him one of only two FBS quarterbacks to Notre Dame Radio Network Paul Burmeister (play-by-play) .903 boast a .900 or above win rate (min. 20 wins), even as Book ranks 14th overall in total QB SiriusXM (Channel 129) Ryan Harris (analyst) career starts (31). His 28 wins are fourth among all FBS quarterbacks. 96.1 FM, 101.5 FM & 960 AM (South Bend) Jack Nolan (reporter) Saturday’s matchup marks the first meeting between Brian Kelly and Mack Brown, the top two winningest active coaches in the FBS by number of wins (Kelly, 271ˆ; Brown, 257). THE SERIES 2 They have also coached the most games (Kelly, 367; Brown, 388) and are the two longest- tenured among active FBS coaches (Kelly, 30th year; Brown, 32nd year). Notre Dame leads, 18-2-0 Last meeting: ND 33, UNC 10 (10.7.2017) Of the five longest regular-season winning streaks in college football history, Notre Dame has single-handedly ended three of those streaks: Oklahoma’s 45 (1953-57), Miami’s 36 2020 SCHEDULE (8-0) 3 (1985-88) and Clemson’s 36 (2017-20). -

Grantland Grantland

12/10/13 Kyle Korver's Big Night, and the Day on the Ocean That Made It Possible - The Triangle Blog - Grantland Grantland The NBA's E-League Now Playing: Bad Luck, Tragedy, and Travesty LeBron James Controls the Chessboard Home Features Blogs The Triangle Sports News, Analysis, and Commentary Hollywood Prospectus Pop Culture Contributors Bill Simmons Bill Barnwell Rembert Browne Zach Lowe Katie Baker Chris Ryan Mark Lisanti,ht Wesley Morris Andy Greenwald Brian Phillips Jonah Keri Steven Hyden,da Molly Lambert Andrew Sharp Alex Pappademas,gl Rafe Bartholomew Emily Yoshida www.grantland.com/blog/the-triangle/post/_/id/85159/kyle-korvers-big-night-and-the-day-on-the-ocean-that-made-it-possible 1/10 12/10/13 Kyle Korver's Big Night, and the Day on the Ocean That Made It Possible - The Triangle Blog - Grantland Sean McIndoe Amos Barshad Holly Anderson Charles P. Pierce David Jacoby Bryan Curtis Robert Mays Jay Caspian Kang,jw SEE ALL » Simmons Quarterly Podcasts Video Contact ESPN.com Jump To Navigation Resize Font: A- A+ NBA Kyle Korver's Big Night, and the Day on the Ocean That Made It Possible By Charles Bethea on December 9, 2013 4:45 PM ET,ht www.grantland.com/blog/the-triangle/post/_/id/85159/kyle-korvers-big-night-and-the-day-on-the-ocean-that-made-it-possible 2/10 12/10/13 Kyle Korver's Big Night, and the Day on the Ocean That Made It Possible - The Triangle Blog - Grantland Scott Cunningham/NBAE/Getty Images ACT 1: LAST FRIDAY, AMONG THE KORVERS I'm sitting third row at the Hawks-Cavs game, flanked by two large, handsome Midwesterners. -

Perceptions of Success from Members of the Founding Class of MC Squared STEM High School Jeffrey D

National Louis University Digital Commons@NLU Dissertations 6-2013 The esM sage 2.0: Perceptions of Success from Members of the Founding Class of MC Squared STEM High School Jeffrey D. McClellan National Louis University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nl.edu/diss Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Curriculum and Social Inquiry Commons, Disability and Equity in Education Commons, Educational Leadership Commons, Educational Methods Commons, Elementary and Middle and Secondary Education Administration Commons, Science and Mathematics Education Commons, and the Urban Education Commons Recommended Citation McClellan, Jeffrey D., "The eM ssage 2.0: Perceptions of Success from Members of the Founding Class of MC Squared STEM High School" (2013). Dissertations. 193. https://digitalcommons.nl.edu/diss/193 This Dissertation - Public Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@NLU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@NLU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MESSAGE 2.0: PERCEPTIONS OF SUCCESS FROM MEMBERS OF THE FOUNDING CLASS OF MC SQUARED STEM HIGH SCHOOL Jeffrey D. McClellan Dissertation Educational Leadership Doctoral Program Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of Doctor of Education in the Foster G. McGaw Graduate School National College of Education National-Louis University February, 2013 Copyright by Jeffrey David McClellan, 2013 All rights reserved ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the methods of learning from the student’s perspective in order to understand what made the first graduating class of MC Squared successful. The conceptual model of student success composed of non-academic factors of motivation, social connectedness, and self-management was used for the lens from which to understand the six students in depth. -

10/10 Miami Hurricanes #23/21 Florida State Seminoles

20162016 FSU FSU FOOTBALL FOOTBALL | GM| GM 3:6: 2:1: LOUISVILLEMIAMI OLECHARLESTON MISS SOUTHERN #23/21 FLORIDA #10/10 MIAMI STATE SEMINOLES HURRICANES 4-0 1-0 ACC game 3-2 VS 6 0-2 ACC MIAMI HURRICANES Head Coach TEAM COMPARISON Head Coach Oct. 8, 2016 | Miami Gardens, Fla. Jimbo Fisher (Salem ‘89) Mark Richt (Miami ‘82) Hard Rock Stadium (65,285) Career Record: 71-16 | 7th Season 41.4 SCORING OFFENSE 47.0 Career Record: 149-51 | 16th Season Record at FSU: 71-16 | 7th Season 35.4 SCORING DEFENSE 11.0 Record at Miami: 4-0 | 1st Season ABC | 8:14 PM 240.4 RUSHING OFFENSE 232.5 STAT LEADERS 191.2 RUSHING DEFENSE 115.5 STAT LEADERS GAME COVERAGE RUSHING | #4 DALVIN COOK 268.4 PASSING OFFENSE 241.8 RUSHING | #1 MARK WALTON TELEVISION | ABC 107-635, 7 TD, 5.9 ypr, 127.0 ypg 247.2 PASSING DEFENSE 137.8 63-445, 8 TD, 7.1 ypr, 111.2 ypg PBP: Chris Fowler | Analyst: Kirk Herbstreit 508.8 TOTAL OFFENSE 474.2 PASSING | #12 DEONDRE FRANCOIS PASSING | #15 BRAD KAAYA Sidelines: Samantha Ponder 438.4 TOTAL DEFENSE 253.2 96-153-1323, 7 TD/2 INT, 264.6 ypg 63-95-935, 8 TD/3 INT, 233.8 ypg RADIO | SEMINOLE IMG SPORTS NETWORK PBP: Gene Deckerhoff | Analyst: William Floyd RECEIVING | #3 JESUS WILSON ALL-TIME RESULTS RECEIVING | #3 STACY COLEY Sidelines: Tom Block 22-340, 1 TD, 15.5 ypc, 68.0 ypg Miami leads, 31-29 15-211, 4 TD, 14.1 ypc, 52.8 ypg Last: FSU def. -

LSU Basketball Vs

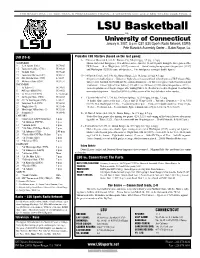

THE BRADY ERA | In 10th YEAR, 6 POSTSEASON TOURN., 3 WESTERN DIV. and 2 SEC TITLES; 2006 FINAL 4 LSU Basketball vs. University of Connecticut January 6, 2007, 8 p.m. CST (LSU Sports Radio Network, ESPN) Pete Maravich Assembly Center -- Baton Rogue, La. LSU (10-3) Probable LSU Starters (based on the last game): G -- 2Dameon Mason (6-6, 183, Jr., Kansas City, Mo.) 8.0 ppg, 3.5 rpg, 1.2 apg NOVEMBER Mason started last four games, 11 in all this season ... Had 14, 13 and 11 points during the three games of the 9 E. A. Sports (Exh.) W, 70-65 HCF Classic ... 14 vs. Wright State (12/27) season est ... Out of starting lineup against Oregon State (12/17) 15 Louisiana College (Exh.) W, 94-41 and Washington (12/20) because of migraines ... Five total games scoring in double figures. 17 Nicholls State W, 96-42 19 Louisiana-Monroe (CST) W, 88-57 G -- 14 Garrett Temple (6-5, 190, So., Baton Rouge, La.) 10.2 ppg, 2.8 rpg, 4.1 apg 25 #24 Wichita State (CST) L, 53-57 Six games in double figures ... Had career highs of seven assists in back-to-back games of HCF Classic (Miss. 29 McNeese State (CST) W, 91-57 Valley, 12/28; Samford 12/29) with just five combined turnovers ... In first seven games had 23 assists and just DECEMBER 7 turnovers ... Career high of 18 at Tulane (12/2) with 17 vs. McNeese (11/29) and at Oregon State (12/17) ... 2 At Tulane (1) W, 74-67 Earned reputation as defensive stopper after holding Duke’s J.J. -

Examining Television Narrative Structure

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Scholarship and Professional Work - Communication College of Communication 2002 Re(de)fining Narrative Events: Examining Television Narrative Structure M. J. Porter D. L. Larson Allison Harthcock Butler University, [email protected] K. B. Nellis Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ccom_papers Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Porter, M.J., Larson, D.L., Harthcock, A., & Nellis, K.B. (2002). Re(de)fining narrative events: Examining television narrative structure, Journal of Popular Film and Television, 30, 23-30. Available from: digitalcommons.butler.edu/ccom_papers/9/ This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Communication at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarship and Professional Work - Communication by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Re(de)fining Narrative Events: Examining Television Narrative Structure. This is an electronic version of an article published in Porter, M.J., Larson, D.L., Harthcock, A., & Nellis, K.B. (2002). Re(de)fining narrative events: Examining television narrative structure, Journal of Popular Film and Television, 30, 23-30. The print edition of Journal of Popular Film and Television is available online at: http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals/VJPF Television's narratives serve as our society's major storyteller, reflecting our values and defining our assumptions about the nature of reality (Fiske and Hartley 85). On a daily basis, television viewers are presented with stories of heroes and villains caught in the recurring turmoil of interrelationships or in the extraordinary circumstances of epic situations. -

03FB Guide P001-030

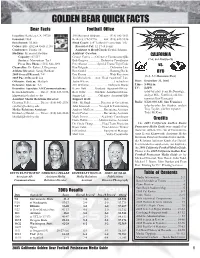

GOLDEN BEAR QUICK FACTS Bear Facts Football Office Location: Berkeley, CA 94720 209 Memorial Stadium ............ (510) 642-3851 Founded: 1868 Berkeley, CA 94720 ........ Fax: (510) 643-9336 Enrollment: 33,000 Head Coach: Jeff Tedford (Fresno State ’83) Colors: Blue (282) & Gold (116) Record at Cal: 32-17 (4 years) Conference: Pacific-10 Assistant to Head Coach: Debbie Schram Stadium: Memorial Stadium Assistant Coaches: Capacity: 67,537 George Cortez ..... Offensive Coordinator/QBs CALIFORNIA Surface: Momentum Turf Bob Gregory ................ Defensive Coordinator (7-4, 4-4 Pacific-10) Press Box Phone: (510) 642-3098 Pete Alamar ............ Special Teams/Tight Ends vs. Chancellor: Dr. Robert J. Birgeneau Ken Delgado ............................. Defensive Line Athletic Director: Sandy Barbour Ron Gould ................................ Running Backs BYU 2005 Overall Record: 7-4 Eric Kiesau .............................. Wide Receivers (6-5, 5-3 Mountain West) 2005 Pac-10 Record: 4-4 Jim Michalczik .... Asst. Head Coach/Off. Line Offensive System: Multiple Justin Wilcox ................................. Linebackers Date: December 22, 2005 Defensive System: 4-3 J.D. Williams ......................... Defensive Backs Time: 5:00 p.m. Executive Associate AD/Communications: Kevin Daft ........... Graduate Assistant-Offense TV: ESPN Kevin Klintworth ........ Direct: (510) 643-9036 Bert Watts .......... Graduate Assistant-Defense (play-by-play Sean McDonough, [email protected] Sanjay Lal ................ Offensive Assistant/QBs analyst Mike Gottfried, sideline Assistant Media Relations Director: Support Staff: reporter Alex Flanagan) Christina Teller ............ Direct: (510) 643-2938 Mike McHugh ............. Director of Operations Radio: KGO-810 AM, San Francisco [email protected] John Krasinski .......... Strength & Conditioning (play-by-play Joe Starkey, analyst Media Relations Assistant: Andrew McGraw ............ Recruiting Assistant Troy Taylor, sideline reporter Kimberley Hoidal ........ Direct: (510) 643-5846 Kevin Parker ................... -

Dale Hansen , Sports Anchor, WFAA 8

The Rotary Club THE HUB of Park Cities Volume 71, Number 25 www.parkcitiesrotary.org February 14, 2020 Serving to Make a Difference Since 1948 TODAY’S PROGRAM Program Chairs of the Day: Jeff Brady Dale Hansen, Sports Anchor, WFAA 8 Dale Hansen is the weeknight sports anchor during the 10 Hansen's other awards and honors include: p.m. newscast on WFAA, Channel 8 in Dallas Texas. He also • Dallas Peace and Justice Center's 2019 Inspiration Award hosts Dale Hansen's Sports Special on Sundays at 10:35 p.m.. • Hero of Hope Award from the Cathedral of Hope Church He's well known for his acclaimed "Unplugged" segments. • Peacemaker Award from the Turtle Creek Chorale Hansen began his career as a radio disc jockey and opera- • Children's Hero Award from TexProtects tions manager in Newton, Iowa. This was followed by a job as a • Distinguished Professional Achievement Award from the UNT sports reporter at KMTV in Omaha, Nebraska. Hansen's first job School of Journalism in Dallas was with KDFW-TV (Channel 4). He joined WFAA-TV in • Communicator of the Year by the National Speech and Debate 1983. Association In 1987, Hansen was honored with the George Foster Pea- • Recipient of over 20 Lone Star EMMY Awards body Award for Distinguished Journalism. That same year, he won • Sportscaster of the Year on two occasions by the Associated the duPont-Columbia Award for his contribution to the investiga- Press tion of SMU's football program. As a result of this investigation, • Texas Sportscaster of the Year on three occasions by the the NCAA prohibited SMU from fielding a football program in 1987. -

Editorial: a Tale of Two Banks

1 Complimentary to churches ft/if* < / V // and community groups priority ©jijwrtumttj Jim* 2730 STEMMONS FRWY STE. 1202 TOWER WEST, DALLAS, TEXAS 75207 ©ov VOLUME 5, NO. 6 June, 1996 TPA Dallas Cowboys' star receiver Michael irvin joins a long list of other prominent African American sports stars flayed by the media. Are they unfair targets? Holiday with a Difference: Our annual Editorial: The reasons for and against bachelor of A tale of celebrating Juneteenth the year two banks vary within the community entry form From The Editor Chris Pryer ^ photo by Derrtck Walters Tike real issue . Just when it seemed that the bank statement of intent is called accountabil extol the virtues of our religious leaders The African American community ing community had gotten about as ity. Once you open your mouth, then and the on-going commitment to the continues to feel powerless, disenfran strange as possible, the paradox in styles everyone knows when you succeed or African American Museum; there has chised and second class when it comes to that exists between two of our larger fail Also, the size of the goal reflects a real been very little work done within the the educational performance of its chil financial institutions struck. While most level of thought and consideration of the lending arena by the bank. While the sup dren. Its inherent distrust of Whites of the banks still have a way to go before real need and capacity to handle this level port of the clergy and the museum are makes for the kind of polarization we are reaching perfection, there has been a of credit activity. -

Interview with Chris Fowler, Digger Phelps, and Dick Vitale of ESPN April 1, 1995

Administration of William J. Clinton, 1995 / Apr. 1 grams and over 100,000 bureaucrats from the for education and training, a tax deduction for Federal budget, and still increase our investment education costs after high school. in education. Now in the past, education and training have Now, many in Congress think there's no dif- enjoyed broad, bipartisan support. Last year, ference in education and other spending. For with strong support from Republicans and example, there are proposals to reduce funding Democrats, Congress enacted my proposals to for Head Start; for public school efforts to meet help students and schools meet the challenges the national education goals; for our national of today and tomorrow. Educational experts said service program, Ameri- Corps, which provides we did more for education by expanding Head scholarship money for young people who will Start, expanding apprenticeships, expanding col- work at minimum wage jobs in local community lege loans than any session of Congress in 30 service projects; even proposals to reduce school years. lunch funding. There are proposals to eliminate Now in this new Congress, some want to cut education, and that's wrong. Gibbs Magnet our efforts for safe and drug-free schools alto- School is a reflection of what we ought to be gether and, unbelievably, to cut the college loan doing more of in America. I don't know what programs. political party these children belong to, but I These are not wise proposals. Here at Gibbs, do know we need them all and they deserve where students are preparing for the 21st cen- our best efforts to give them a shot at the Amer- tury, close to 50 percent of the students depend ican dream. -

Saturday Listings Sunday Listings

6 – THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 10, 2020 GAINESVILLE DAILY REGISTER SATURDAY LISTINGS SEPTEMBER 12 PRIME TIME S1 – DISH NETWORK S2 - DIRECTV 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM S1S2 Fox 4 News Saturday (N) MLB Baseball Houston Astros at Los Angeles Dodgers Site: Dodger Stadium -- Los Angeles, Calif. (L) Fox 4 News at 9:00 p.m. (N) Labor of Love (4) "10 Things Kristy 4 4 KDFW (4) Likes About You" NBC 5 News at Wingstop NHL Hockey Stanley Cup Playoffs (L) NBC5 News at Saturday Night Live (5) 6:00 p.m. Inside High 10:00 p.m. (N) 5 5 KXAS (5) Saturday (N) School Sports Jeopardy! Wheel Fortune FC Dallas Live MLS Soccer FC Dallas at Houston Dynamo Site: BBVA Compass NCIS: New Orleans "Powder Madam Secretary "So It Goes" (21) "Delicious (L) Stadium -- Houston, Texas (L) Keg" 21 21 KTXA (6) Destinations" Religious Programming Michael Kenneth W. The Green In Touch With Dr. Charles Perry Stone: Love Israel Israel: The (2) Youssef Hagin Room Stanley Manna-Fest With Baruch Prophetic 2 KDTN (7) Korman Connection College Football College Football Scoreboard (L) /NCAA Football Clemson at Wake Forest Site: BB&T Field -- College News 8 Entertainment Tonight (8) Scoreboard (L) Winston-Salem, N.C. (L) Football Update at Weekend 8 8 WFAA (8) Scoreboard (L) 10:00 p.m. (N) <++++ Titanic (1997, Drama) Leonardo DiCaprio, Victor Garber, Kate Winslet. Noticiero Noticias Somos cowboys (39) Telemundo 39 Telemundo Fin 39 39 KXTX (9) at 10pm (N) de semana (N) CBS 11 News at Paid Program CBS Saturday Encore Love Island: More to Love (N) 48 Hours (SP) (N) CBS 11 News Saturday at Cowboys (11) 6:00 p.m.