Effects of Recruiter Characteristics on Recruiting Effectiveness in Division I Women's Soccer Marshall J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE DAILY SCOREBOARD NFL Standings Monday Night Football Latest Line AMERICAN CONFERENCE EAGLES 28, REDSKINS 13 NFL East Washington

10 – THE DERRICK. / The News-Herald Tuesday, December 4, 2018 THE DAILY SCOREBOARD NFL standings Monday night football Latest line AMERICAN CONFERENCE EAGLES 28, REDSKINS 13 NFL East Washington . .0 13 0 0—13 Favorite Points Underdog W L T Pct PF PA Philadelphia . .7 7 0 14—28 Thursday New England 9 3 0 .750 331 259 TITANS 4.5 (37.5) Jaguars Miami 6 6 0 .500 244 300 First Quarter Sunday Buffalo 4 8 0 .333 178 293 Phi—Tate 6 pass from Wentz (Elliott kick), 7:31. CHIEFS 7 (53.5) Ravens N.Y. Jets 3 9 0 .250 243 307 Second Quarter TEXANS 4.5 (48.5) Colts South Was—FG Hopkins 44, 13:46. Panthers 1 (46.5) BROWNS W L T Pct PF PA Was—Peterson 90 run (Hopkins kick), 9:23. PACKERS 6 (48.5) Falcons Houston 9 3 0 .750 302 235 Phi—Sproles 14 run (Elliott kick), 1:46. Saints 8 (57.5) BUCS Indianapolis 6 6 0 .500 325 279 Was—FG Hopkins 47, :15. BILLS 3.5 (38.5) Jets Tennessee 6 6 0 .500 221 245 Fourth Quarter Patriots 8 (47.5) DOLPHINS Jacksonville 4 8 0 .333 203 243 Phi—Matthews 4 pass from Wentz (Tate pass from Rams 3 (52.5) BEARS North Wentz), 14:10. WASHINGTON NL (NL) Giants W L T Pct PF PA Phi—FG Elliott 46, 11:41. Broncos 6 (43.5) 49ERS Pittsburgh 7 4 1 .625 346 282 Phi—FG Elliott 44, 4:48. CHARGERS 14 (47.5) Bengals Baltimore 7 5 0 .583 297 214 A—69,696. -

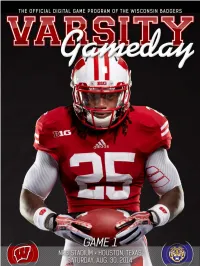

Varsity Gameday Vs

CONTENTS GAME 1: WISCONSIN VS. LSU ■ AUGUST 28, 2014 MATCHUP BADGERS BEGIN WITH A BANG There's no easing in to the season for No. 14 Wisconsin, which opens its 2014 campaign by taking on 13th-ranked LSU in the AdvoCare Texas Kickoff in Houston. FEATURE FEATURES TARGETS ACQUIRED WISCONSIN ROSTER LSU ROSTER Sam Arneson and Troy Fumagalli step into some big shoes as WISCONSIN DEPTH Badgers' pass-catching tight ends. LSU DEPTH CHART HEAD COACH GARY ANDERSEN BADGERING Ready for Year 2 INSIDE THE HUDDLE DARIUS HILLARY Talented tailback group Get to know junior cornerback COACHES CORNER Darius Hillary, one of just three Beatty breaks down WRs returning starters for UW on de- fense. Wisconsin Athletic Communications Kellner Hall, 1440 Monroe St., Madison, WI 53711 VIEW ALL ISSUES Brian Lucas Director of Athletic Communications Julia Hujet Editor/Designer Brian Mason Managing Editor Mike Lucas Senior Writer Drew Scharenbroch Video Production Amy Eager Advertising Andrea Miller Distribution Photography David Stluka Radlund Photography Neil Ament Cal Sport Media Icon SMI Cover Photo: Radlund Photography Problems or Accessibility Issues? [email protected] © 2014 Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. All rights reserved worldwide. GAME 1: LSU BADGERS OPEN 2014 IN A BIG WAY #14/14 WISCONSIN vs. #13/13 LSU Aug. 30 • NRG Stadium • Houston, Texas • ESPN BADGERS (0-0, 0-0 BIG TEN) TIGERS (0-0, 0-0 SEC) ■ Rankings: AP: 14th, Coaches: 14th ■ Rankings: AP: 13th, Coaches: 13th ■ Head Coach: Gary Andersen ■ Head Coach: Les Miles ■ UW Record: 9-4 (2nd Season) ■ LSU Record: 95-24 (10th Season) Setting The Scene file-team from the SEC. -

Heisman Trophy Trust, Which Annually Presents the Heisman Memorial William J

Heisman Trophy Trust DEVONTA SMITH OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA SELECTED AS THE 2020 HEISMAN TROPHY WINNER Trustees: DeVonta Smith of Alabama was selected as the 86th winner of the Heisman Memorial Trophy as Michael J. Comerford President the Outstanding College Football Player in the United States for 2020. James E. Corcoran Anne Donahue, of the Heisman Trophy Trust, which annually presents the Heisman Memorial William J. Dockery Trophy Award, announced the selection of Smith on Tuesday evening, January 5, 2021, on a Anne F. Donahue nationally televised ESPN sports special live broadcast from the ESPN Studio in Bristol, N. Richard Kalikow Connecticut. Vasili Krishnamurti Brian D. Obergfell The victory for the 6’1”, 175-pound Smith represents the third winner from Alabama, joining Carol A. Pisano Mark Ingram (2009) and Derrick Henry (2015). He is the 4th wide receiver to win the Heisman Sanford Wurmfeld and the first since Desmond Howard in 1991. Honorable John E. Sprizzo Smith, of Amite, LA caught 105 passes for 1,641 yards and 20 touchdowns including a 1934-2008 tremendous performance in the College Football Playoff Semi-Final catching 7 passes for 130 yards and 3 touchdowns. His career receiving yards of 3,260 is highest in Alabama history. Smith also holds the SEC career record for receiving touchdowns with 40, passing the previous Robert Whalen Executive Director mark of 31 held by Amari Cooper and Chris Doering. He also owns a four- and five-touchdown Timothy Henning game making him the only receiver in SEC history with multiple career games totaling four or Associate Director more receiving touchdowns. -

Promoting the Heisman Trophy: Coorientation As It Applies to Promoting Heisman Trophy Candidates Stephen Paul Warnke Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1992 Promoting the Heisman Trophy: coorientation as it applies to promoting Heisman Trophy candidates Stephen Paul Warnke Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Business and Corporate Communications Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Warnke, Stephen Paul, "Promoting the Heisman Trophy: coorientation as it applies to promoting Heisman Trophy candidates" (1992). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 74. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/74 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Promoting the Heisman Trophy: Coorientation as it applies to promoting Heisman Trophy candidates by Stephen-Paul Warnke A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department: English Major: Business and Technical Communication Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1992 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 HISTORY OF HEISMAN 5 HEISMAN FACTORS 7 Media Exposure 8 Individual Factors 13 Team Factors 18 Analysis of Factors 22 Coorientation Model 26 COMMUNICATION PROCESS -

Edward D. Krzemienski Ball State University Office Phone: 765-285

Edward D. Krzemienski Ball State University Office phone: 765-285-8770 Department of History Office fax: 765-285-5612 Muncie, IN 47306 Home phone: 765-896-8916 [email protected] Cell phone: 843-991-0820 Education Ph.D. History, Purdue University (West Lafayette, IN), 2015 M.A. History, Kent State University (Kent, OH), 1994 B.A. History, Kent State University (Kent, OH), 1988 B.A. Political Science, Kent State University (Kent, OH), 1988 Minor Certificate Geography, Kent State University (Kent, OH), 1988 Professional Experience Instructor of History, Ball State University, 2008-present Visiting Professor of History, Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis, 1996-2000 and 2004-present Visiting Assistant Professor of History, The Citadel, the Military College of South Carolina, 2000-2004 Teaching Assistant, Purdue University, 1996-2000 Lecturer, Kent State University’s Geneva, Switzerland Program, spring semester 1990 Selected Publications and Presentations Political Football: Race, College Football and the Troubled Path to Desegregation in the 1960s. Book manuscript, (basis for HBO Documentary, Breaking the Huddle). Currently under solicited consideration. Rising Tide: Bear Bryant, Joe Namath, and Dixie’s Last Quarter. Co-authored with Randy Roberts (NY: Twelve, 2013). “Changing Gears Interactive Documentary.” Project Historian. Project director, James J. Connolly, Ball State University Center for Middletown Studies. Namath. Special contributing assistant to the director. Home Box Office (dir. Joe Lavine). Premier airdate: 28 January 2012 at 9:00 P.M., EST. Black Baseball in Indiana. Consultant and commentator. Project director, Geri Strecker, Virginia B. Ball Center for Creative Inquiry. Premier showing: 27 April 2011, 6:30 P.M., EST at Cornerstone Center for the Performing Arts, Muncie, Indiana. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

2013 - 2014 Media Guide

2013 - 2014 MEDIA GUIDE www.bcsfootball.org The Coaches’ Trophy Each year the winner of the BCS National Champi- onship Game is presented with The Coaches’ Trophy in an on-field ceremony after the game. The current presenting sponsor of the trophy is Dr Pepper. The Coaches’ Trophy is a trademark and copyright image owned by the American Football Coaches As- sociation. It has been awarded to the top team in the Coaches’ Poll since 1986. The USA Today Coaches’ Poll is one of the elements in the BCS Standings. The Trophy — valued at $30,000 — features a foot- ball made of Waterford® Crystal and an ebony base. The winning institution retains The Trophy for perma- nent display on campus. Any portrayal of The Coaches’ Trophy must be li- censed through the AFCA and must clearly indicate the AFCA’s ownership of The Coaches’ Trophy. Specific licensing information and criteria and a his- tory of The Coaches’ Trophy are available at www.championlicensing.com. TABLE OF CONTENTS AFCA Football Coaches’ Trophy ............................................IFC Table of Contents .........................................................................1 BCS Media Contacts/Governance Groups ...............................2-3 Important Dates ...........................................................................4 The 2013-14 Bowl Championship Series ...............................5-11 The BCS Standings ....................................................................12 College Football Playoff .......................................................13-14 -

2017 National College Football Awards Association Master Calendar

2017 National College Football 9/20/2017 1:58:08 PM Awards Association Master Calendar Award ...................................................Watch List Semifinalists Finalists Winner Banquet/Presentation Bednarik Award .................................July 10 Oct. 30 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] March 9, 2018 (Atlantic City, N.J.) Biletnikoff Award ...............................July 18 Nov. 13 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] Feb. 10, 2018 (Tallahassee, Fla.) Bronko Nagurski Trophy ...................July 13 Nov. 16 Dec. 4 Dec. 4 (Charlotte) Broyles Award .................................... Nov. 21 Nov. 27 Dec. 5 [RCS] Dec. 5 (Little Rock, Ark.) Butkus Award .....................................July 17 Oct. 30 Nov. 20 Dec. 5 Dec. 5 (Winner’s Campus) Davey O’Brien Award ........................July 19 Nov. 7 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] Feb. 19, 2018 (Fort Worth) Disney Sports Spirit Award .............. Dec. 7 [THDA] Dec. 7 (Atlanta) Doak Walker Award ..........................July 20 Nov. 15 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] Feb. 16, 2018 (Dallas) Eddie Robinson Award ...................... Dec. 5 Dec. 14 Jan. 6, 2018 (Atlanta) Gene Stallings Award ....................... May 2018 (Dallas) George Munger Award ..................... Nov. 16 Dec. 11 Dec. 27 March 9, 2018 (Atlantic City, N.J.) Heisman Trophy .................................. Dec. 4 Dec. 9 [ESPN] Dec. 10 (New York) John Mackey Award .........................July 11 Nov. 14 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [RCS] TBA Lou Groza Award ................................July 12 Nov. 2 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] Dec. 4 (West Palm Beach, Fla.) Maxwell Award .................................July 10 Oct. 30 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] March 9, 2018 (Atlantic City, N.J.) Outland Trophy ....................................July 13 Nov. 15 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] Jan. 10, 2018 (Omaha) Paul Hornung Award .........................July 17 Nov. 9 Dec. 6 TBA (Louisville) Paycom Jim Thorpe Award ..............July 14 Oct. -

Doane-Mastersreport-2019

DISCLAIMER: This document does not meet current format guidelines Graduate School at the The University of Texas at Austin. of the It has been published for informational use only. Running Head: EXPLOITATION IN COLLEGE SPORTS 1 Exploitation in College Sports: The Amateurism Hoax and the True Value of an Education Bill Doane The University of Texas at Austin EXPLOITATION IN COLLEGE SPORTS 2 Exploitation in College Sports The Amateurism Hoax and the True Value of an Education Introduction Racism and exploitation in intercollegiate athletics have garnered a great deal of scholarly attention over the last thirty years. As athletic departments’ revenues from ticket sales and from football and men’s basketball television contracts continue to grow, the critical discourse regarding the treatment of student-athletes mounts. Between 1996 and 2013, the TV contracts for major college football grew from $185 million to $725 million, and the 2017 NCAA March Madness basketball tournament generated $1.1 billion in television rights alone. However, the NCAA national office is not alone in such riches. Individual universities enjoy sizeable revenues from their successful football and men’s basketball teams with schools like the University of Wisconsin and the University of California, Los Angeles, receiving $6.5 million each for merely participating in the 1994 Rose Bowl Game, the post-season event dubbed “The Granddaddy of Them All” (Eitzen, 1996). Some of these bowl game revenues are passed along to college coaches in the form of incentive bonuses on top of their considerable salaries (the average salary for major college football head coach during the 2016-2017 academic year was in excess of $3.3 million) but most of these revenues are reinvested in the program or used to support other, non-revenue generating teams on campus. -

ESPN, INC.: CORPORATE ETHICS PLAN Marianne Mcgoldrick Values

ESPN, INC.: CORPORATE ETHICS PLAN Marianne McGoldrick Values and Ethics Management in PR October 6, 2013 McGoldrick 2 Introduction The following is a business profile, corporate ethics plan and budget to be implemented by ESPN, Inc. (ESPN), the leading multinational, multimedia sports entertainment company. The corporate ethics plan provides guidance to ESPN executives on how a traditional Standards of Business Conduct with be developed, implemented and moderated across the organization. It also reviews why it is necessary to introduce Standards of Business Conduct to employees, based on both recent ethical issues within the organization and philosophical justification. The plan will help ESPN maintain a healthy public image and corporate culture while raising ethical awareness internally. McGoldrick 3 Business Profile ESPN, Inc. (ESPN), The Worldwide Leader in Sports, is the leading multinational, multimedia sports entertainment company based in Bristol, CT.i Mission: “To serve sports fans wherever sports are watched, listened to, discussed, debated, read about or played.”ii Ownership: ABC, Inc., an indirect subsidiary of The Walt Disney Company, owns 80 percent of ESPN, Inc. The Hearst Corporation holds 20 percent interest.iii Employees: Four thousand employees work at the ESPN Plaza in Bristol (7,000 employees worldwide).iv ESPN’s 7,000 employees include the following key executives:v John D. Skipper, President Paul Cushing, Chief Information Officer and Senior Vice President of Management Information Technology Christine Driessen, Chief Financial Officer and Executive Vice President Chuck Pagano, Chief Technology Officer and Executive Vice President Edward Erhardt, President of Customer Marketing and Sales John Kosner, Executive Vice President of ESPN Digital and Print Media John A. -

Angell, Roger

Master Bibliography (1,000+ Entries) Aamidor, Abe. “Sports: Have We Lost Control of Our Content [to Sports Leagues That Insist on Holding Copyright]?” Quill 89, no. 4 (2001): 16-20. Aamidor, Abraham, ed. Real Sports Reporting. Bloomington, Ind.: University of Indiana Press, 2003. Absher, Frank. “[Baseball on Radio in St. Louis] Before Buck.” St. Louis Journalism Review 30, no. 220 (1999): 1-2. Absher, Frank. “Play-by-Play from Station to Station [and the History of Baseball on Midwest Radio].” St. Louis Journalism Review 35, no. 275 (2005): 14-15. Ackert, Kristie. “Devils Radio Analyst and Former Daily News Sportswriter Sherry Ross Due [New Jersey State] Honor for Historic Broadcast [After Becoming First Woman to Do Play-by-Play of a Full NHL Game in English].” Daily News (New York), 16 March 2010, http://www.nydailynews.com/sports/hockey/devils-radio-analyst-daily- news-sportswriter-sherry-ross-due-honor-historic-broadcast-article-1.176580 Ackert, Kristie. “No More ‘Baby’ Talk. [Column Reflects on Writer’s Encounters with Sexual Harassment Amid ESPN Analyst Ron Franklin Calling Sideline Reporter Jeannine Edwards ‘Sweet Baby’].” Daily News (New York), 9 January 2011, 60. Adams, Terry, and Charles A. Tuggle. “ESPN’s SportsCenter and Coverage of Women’s Athletics: ‘It’s a Boy’s Club.’” Mass Communication & Society 7, no. 2 (2004): 237- 248. Airne, David J. “Silent Sexuality: An Examination of the Role(s) Fans Play in Hiding Athletes’ Sexuality.” Paper presented at the annual conference of the National Communication Association, Chicago, November 2007. Allen, Maury. “White On! Bill [White] Breaks Color Line in [Baseball] Broadcast Booth. -

'Inside Sports': a Framing Analysis of College Gameday

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2007 ESPN’s Ability to Get Fans ‘Inside Sports’: A Framing Analysis of College Gameday Melissa Lovette University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Other Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Lovette, Melissa, "ESPN’s Ability to Get Fans ‘Inside Sports’: A Framing Analysis of College Gameday. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/304 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Melissa Lovette entitled "ESPN’s Ability to Get Fans ‘Inside Sports’: A Framing Analysis of College Gameday." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Sport Studies. Robin Hardin, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Dennie Kelley, Lars Dzikus Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Melissa Lovette entitled “ESPN’s Ability to Get Fans ‘Inside Sports’: A Framing Analysis of College Gameday.” I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Sport Studies.