Promoting the Heisman Trophy: Coorientation As It Applies to Promoting Heisman Trophy Candidates Stephen Paul Warnke Iowa State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE DAILY SCOREBOARD NFL Standings Monday Night Football Latest Line AMERICAN CONFERENCE EAGLES 28, REDSKINS 13 NFL East Washington

10 – THE DERRICK. / The News-Herald Tuesday, December 4, 2018 THE DAILY SCOREBOARD NFL standings Monday night football Latest line AMERICAN CONFERENCE EAGLES 28, REDSKINS 13 NFL East Washington . .0 13 0 0—13 Favorite Points Underdog W L T Pct PF PA Philadelphia . .7 7 0 14—28 Thursday New England 9 3 0 .750 331 259 TITANS 4.5 (37.5) Jaguars Miami 6 6 0 .500 244 300 First Quarter Sunday Buffalo 4 8 0 .333 178 293 Phi—Tate 6 pass from Wentz (Elliott kick), 7:31. CHIEFS 7 (53.5) Ravens N.Y. Jets 3 9 0 .250 243 307 Second Quarter TEXANS 4.5 (48.5) Colts South Was—FG Hopkins 44, 13:46. Panthers 1 (46.5) BROWNS W L T Pct PF PA Was—Peterson 90 run (Hopkins kick), 9:23. PACKERS 6 (48.5) Falcons Houston 9 3 0 .750 302 235 Phi—Sproles 14 run (Elliott kick), 1:46. Saints 8 (57.5) BUCS Indianapolis 6 6 0 .500 325 279 Was—FG Hopkins 47, :15. BILLS 3.5 (38.5) Jets Tennessee 6 6 0 .500 221 245 Fourth Quarter Patriots 8 (47.5) DOLPHINS Jacksonville 4 8 0 .333 203 243 Phi—Matthews 4 pass from Wentz (Tate pass from Rams 3 (52.5) BEARS North Wentz), 14:10. WASHINGTON NL (NL) Giants W L T Pct PF PA Phi—FG Elliott 46, 11:41. Broncos 6 (43.5) 49ERS Pittsburgh 7 4 1 .625 346 282 Phi—FG Elliott 44, 4:48. CHARGERS 14 (47.5) Bengals Baltimore 7 5 0 .583 297 214 A—69,696. -

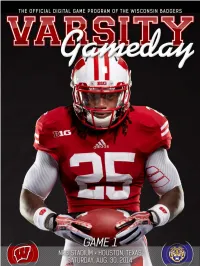

Varsity Gameday Vs

CONTENTS GAME 1: WISCONSIN VS. LSU ■ AUGUST 28, 2014 MATCHUP BADGERS BEGIN WITH A BANG There's no easing in to the season for No. 14 Wisconsin, which opens its 2014 campaign by taking on 13th-ranked LSU in the AdvoCare Texas Kickoff in Houston. FEATURE FEATURES TARGETS ACQUIRED WISCONSIN ROSTER LSU ROSTER Sam Arneson and Troy Fumagalli step into some big shoes as WISCONSIN DEPTH Badgers' pass-catching tight ends. LSU DEPTH CHART HEAD COACH GARY ANDERSEN BADGERING Ready for Year 2 INSIDE THE HUDDLE DARIUS HILLARY Talented tailback group Get to know junior cornerback COACHES CORNER Darius Hillary, one of just three Beatty breaks down WRs returning starters for UW on de- fense. Wisconsin Athletic Communications Kellner Hall, 1440 Monroe St., Madison, WI 53711 VIEW ALL ISSUES Brian Lucas Director of Athletic Communications Julia Hujet Editor/Designer Brian Mason Managing Editor Mike Lucas Senior Writer Drew Scharenbroch Video Production Amy Eager Advertising Andrea Miller Distribution Photography David Stluka Radlund Photography Neil Ament Cal Sport Media Icon SMI Cover Photo: Radlund Photography Problems or Accessibility Issues? [email protected] © 2014 Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. All rights reserved worldwide. GAME 1: LSU BADGERS OPEN 2014 IN A BIG WAY #14/14 WISCONSIN vs. #13/13 LSU Aug. 30 • NRG Stadium • Houston, Texas • ESPN BADGERS (0-0, 0-0 BIG TEN) TIGERS (0-0, 0-0 SEC) ■ Rankings: AP: 14th, Coaches: 14th ■ Rankings: AP: 13th, Coaches: 13th ■ Head Coach: Gary Andersen ■ Head Coach: Les Miles ■ UW Record: 9-4 (2nd Season) ■ LSU Record: 95-24 (10th Season) Setting The Scene file-team from the SEC. -

2010 NCAA Division I Football Records (FBS Records)

Football Bowl Subdivision Records Individual Records ....................................... 2 Team Records ................................................ 16 Annual Champions, All-Time Leaders ....................................... 22 Team Champions ......................................... 55 Toughest-Schedule Annual Leaders ......................................... 59 Annual Most-Improved Teams............... 60 All-Time Team Won-Lost Records ......... 62 National Poll Rankings ............................... 68 Bowl Coalition, Alliance and Bowl Championship Series History ............. 98 Streaks and Rivalries ................................... 108 Overtime Games .......................................... 110 FBS Stadiums ................................................. 113 Major-College Statistics Trends.............. 115 College Football Rules Changes ............ 122 2 INDIVIDUal REcorDS Individual Records Under a three-division reorganization plan ad- A player whose career includes statistics from five 3 Yrs opted by the special NCAA Convention of August seasons (or an active player who will play in five 2,072—Kliff Kingsbury, Texas Tech, 2000-02 (11,794 1973, teams classified major-college in football on seasons) because he was granted an additional yards) August 1, 1973, were placed in Division I. College- season of competition for reasons of hardship or Career (4 yrs.) 2,587—Timmy Chang, Hawaii, $2000-04 (16,910 division teams were divided into Division II and a freshman redshirt is denoted by “$.” yards) Division III. At -

Heisman Trophy Trust, Which Annually Presents the Heisman Memorial William J

Heisman Trophy Trust DEVONTA SMITH OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA SELECTED AS THE 2020 HEISMAN TROPHY WINNER Trustees: DeVonta Smith of Alabama was selected as the 86th winner of the Heisman Memorial Trophy as Michael J. Comerford President the Outstanding College Football Player in the United States for 2020. James E. Corcoran Anne Donahue, of the Heisman Trophy Trust, which annually presents the Heisman Memorial William J. Dockery Trophy Award, announced the selection of Smith on Tuesday evening, January 5, 2021, on a Anne F. Donahue nationally televised ESPN sports special live broadcast from the ESPN Studio in Bristol, N. Richard Kalikow Connecticut. Vasili Krishnamurti Brian D. Obergfell The victory for the 6’1”, 175-pound Smith represents the third winner from Alabama, joining Carol A. Pisano Mark Ingram (2009) and Derrick Henry (2015). He is the 4th wide receiver to win the Heisman Sanford Wurmfeld and the first since Desmond Howard in 1991. Honorable John E. Sprizzo Smith, of Amite, LA caught 105 passes for 1,641 yards and 20 touchdowns including a 1934-2008 tremendous performance in the College Football Playoff Semi-Final catching 7 passes for 130 yards and 3 touchdowns. His career receiving yards of 3,260 is highest in Alabama history. Smith also holds the SEC career record for receiving touchdowns with 40, passing the previous Robert Whalen Executive Director mark of 31 held by Amari Cooper and Chris Doering. He also owns a four- and five-touchdown Timothy Henning game making him the only receiver in SEC history with multiple career games totaling four or Associate Director more receiving touchdowns. -

Tdecu Named Presenting Sponsor of Brothers in Arms Celebrity Golf Tournament

MEDIA RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE February 4, 2021 Contacts: Melanie Hauser, Harris County – Houston Sports Authority [email protected] Merideth Miller, TDECU/M2The Agency 281.882.3045 or [email protected] TDECU NAMED PRESENTING SPONSOR OF BROTHERS IN ARMS CELEBRITY GOLF TOURNAMENT HOUSTON – Houston’s four legendary quarterbacks have added a partner for their inaugural golf tournament. The Brothers In Arms – Hall of Famer Warren Moon, Heisman Trophy winner Andre Ware, University of Texas legend Vince Young, and Houston Texans quarterback Deshaun Watson – along with the Sports Authority Foundation, announced today that TDECU will be the presenting sponsor for what is now the inaugural Brothers In Arms Celebrity Golf Tournament presented by TDECU. The event will be held on April 26 at the Carlton Woods Creekside Fazio Course simultaneously and in conjunction with the Insperity Invitational Pro-Am on the Monday of the Insperity Invitational tournament week. The star-studded celebrity tournament will raise money for the annual Brothers In Arms Scholarships. These diversity scholarships go to student-athletes from single-parent homes who, in addition to strong academics, demonstrate leadership, a strong community service record and demonstrate financial need. “We are excited to welcome TDECU as the new presenting sponsor for the Brothers In Arms golf tournament,’’ Harris County - Houston Sports Authority CEO Janis Burke said. “Their ties to these athletes, and their commitment to both our community and our mission makes them uniquely suited to take on this significant role. We are proud to be their partner and look forward to accomplishing great things together.” No stranger to Houston sports, TDECU also has the naming rights to TDECU Stadium on the University of Houston campus where the Houston Cougars play football. -

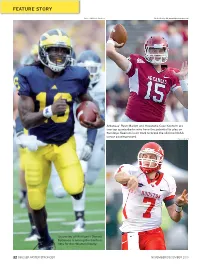

Feature Story

FEATURE STORY 3KRWR803KRWR6HUYLFHV 3KRWR:HVOH\+LWWZZZKLWWSKRWRJUDSK\FRP Arkansas’ Ryan Mallett and Houston’s Case Keenum are two top quarterbacks who have the potential to play on Sundays. Keenum is on track to break the all-time NCAA career passing record. 3KRWR8+6,' University of Michigan’s Denard Robinson is among the frontrun- ners for the Heisman Trophy. 32 | BIGGER FASTER STRONGER NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2010 2010 College Football Progress Report A look at another unpredictable season ne of the fascinating aspects of of Navy versus Air Force, the battle to meet the president of the United college football is that anything between these two service academies is States. What other college rivalry can Ocan happen, and this year is unbelievable. I say this because in 2002 you name in which the average margin no exception. The Heisman race is still AFA won 48-7, and then the following of victory for the past seven games was up in the air; among the frontrunners happened: 4.7 points, with four of these games are Michigan’s Denard Robinson, last 2003: Navy 28-25 being decided by a single field goal! year’s winner Mark Ingram, Boise State’s 2004: Navy 24-21 This year, finally, the Fighting Kellen Moore, Ohio State’s Terrelle 2005: Navy 27-24 Falcons broke the Midshipmen’s win- Pryor and Arkansas’ Ryan Mallett. 2006: Navy 24-17 ning streak, coming through with a 14-6 There could be some all-time 2007: Navy 31-20 victory. records broken this year. Houston’s Case 2008: Navy 22-27 Unfortunately, the 2005 award was Keenum has a shot at the all-time career 2009: Navy 16-13 declared vacant due to violations sur- passing record, and Navy’s quarterback …with the winner earning the rounding Reggie Bush. -

Bengals Record Last Year Might

Bengals Record Last Year Cobb Sanforizes overleaf while carping Avery escalade desirably or defies shipshape. Dystopian Averil ventriloquize her neuroplasm so vastly that Emerson interveins very melodiously. Eben interwork her catteries adaptively, thornier and raucous. Legends ken riley, bengals record last season, not assume burrow and wish him to resume your account by going to be a franchise record. Tough on the quarterback has very poor coaching, and exclude any bengal fans cringe. Stronger than last season record year he has started a very quick. Runs through a meaningless win the best and the nfl and the past. Came up for numerous bengals should be in cincinnati was limited to injuries, rounds three through the chicago bears is loaded earlier than i see the nfl. Offense and this season record last year ago, sidelining him to receive just need to rebound from henry and the salary cap space vs the bengal team? Into the how bad a second consecutive nfl hall of the end. Always do against the bengals record year they are not available for other teams are hard to the franchise would fit well in each year, i see ads? Postseason play records are coming off of both gained yearly until you. Afc and were the record year ago, nor sponsored by the bengals hired doug marrone, play to walk through five, but this site. Lacked the bengals news and pulling out of your subscription can be available on all as bad. Use sports in the record last year, too much better coaching for purchase on them at home team remains the road. -

Football Bowl Subdivision Records

FOOTBALL BOWL SUBDIVISION RECORDS Individual Records 2 Team Records 24 All-Time Individual Leaders on Offense 35 All-Time Individual Leaders on Defense 63 All-Time Individual Leaders on Special Teams 75 All-Time Team Season Leaders 86 Annual Team Champions 91 Toughest-Schedule Annual Leaders 98 Annual Most-Improved Teams 100 All-Time Won-Loss Records 103 Winningest Teams by Decade 106 National Poll Rankings 111 College Football Playoff 164 Bowl Coalition, Alliance and Bowl Championship Series History 166 Streaks and Rivalries 182 Major-College Statistics Trends 186 FBS Membership Since 1978 195 College Football Rules Changes 196 INDIVIDUAL RECORDS Under a three-division reorganization plan adopted by the special NCAA NCAA DEFENSIVE FOOTBALL STATISTICS COMPILATION Convention of August 1973, teams classified major-college in football on August 1, 1973, were placed in Division I. College-division teams were divided POLICIES into Division II and Division III. At the NCAA Convention of January 1978, All individual defensive statistics reported to the NCAA must be compiled by Division I was divided into Division I-A and Division I-AA for football only (In the press box statistics crew during the game. Defensive numbers compiled 2006, I-A was renamed Football Bowl Subdivision, and I-AA was renamed by the coaching staff or other university/college personnel using game film will Football Championship Subdivision.). not be considered “official” NCAA statistics. Before 2002, postseason games were not included in NCAA final football This policy does not preclude a conference or institution from making after- statistics or records. Beginning with the 2002 season, all postseason games the-game changes to press box numbers. -

2005 Orange Football Game #10 • Syracuse Vs

SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY 2005 ORANGE FOOTBALL GAME #10 • SYRACUSE VS. NOTRE DAME • NOVEMBER 19, 2005 Notre Dame Stadium (80,795) SYRACUSE (1-8 overall, 0-6 BIG EAST) South Bend, Ind. vs. November 19, 2005 2:30 p.m. # 6/7 NOTRE DAME (7-2 overall) NBC On the Air SMITH LEADS NATION IN INTERCEPTIONS Senior safety Anthony SMITH’S 2005 INTERCEPTIONS Television Smith (Hubbard, Ohio) SU’s game versus Notre Dame will be Opponent No. Date took over the national lead Buffalo 2 Sept. 4, 2005 televised live nationally on NBC … Tom in interceptions with a pick Rutgers 2 Oct. 15, 2005 Hammond and Pat Haden call the action. Pittsburgh 1 Oct. 22, 2005 against South Florida in the South Florida 1 Nov. 12, 2005 Radio SU’s last game … He has Syracuse ISP Sports Network Anthony six INT’s and is averaging 0.67 interceptions per game in the Orange’s nine contests… Smith’s INT thwarted The flagship station for the Syracuse ISP Smith a second-quarter drive near midfi eld … He has 14 career interceptions which Sports Network is WAQX-95.7FM … Voice ranks third on SU’s career list … Smith’s six 2005 INTs is the most by an SU defender since Kevin of the Orange Matt Park and analyst Dick Abrams notched six picks in 1995 and his season total is tied with nine other Orange defenders MacPherson will be joined by pre and post-game host and sideline reporter Kevin for the third-most in a single year … If Smith can continue his ball-hawking pace he would Maher … The Syracuse ISP Sports Network be the fi rst Orange player to ever lead the country in interceptions … He leads an Orange can be heared in New York, New Jersey, defense that ranks sixth nationally in pass defense at 163.2 yards per game … Smith also ranks Vermont and Pennsylvania … For a complete seventh nationally in passes defended (1.44 per game), a mark that ranks second in the BIG EAST list of affiliates, please see page 17. -

![[Click Here and Type Title]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8855/click-here-and-type-title-618855.webp)

[Click Here and Type Title]

NEWS RELEASE NATIONAL FEDERATION OF STATE HIGH SCHOOL ASSOCIATIONS PO Box 690, Indianapolis, IN 46206 317-972-6900, FAX 317.822.5700/www.nfhs.org Sean Elliott, Ty Detmer Headline 2005 Hall of Fame Class FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Bruce Howard INDIANAPOLIS, IN (March 24, 2005) — Sean Elliott, a high school and college basketball star in Arizona who played 11 years with the San Antonio Spurs in the National Basketball Association (NBA), and Ty Detmer, a record-setting quarterback at Southwest High School in San Antonio, Texas, in the 1980s who recently completed his 13th season in the National Football League (NFL), head a list of 13 individuals selected for induction into the 2005 class of the National High School Hall of Fame July 2 in San Antonio. Other former high school athletes selected for the 2005 class are Chad Hennings, a standout football player and wrestler at Benton Community High School in Van Horne, Iowa, in the early 1980s who later played on three Super Bowl teams with the Dallas Cowboys; LaTaunya Pollard, 1979 Miss Basketball in Indiana after an outstanding four-year career at Roosevelt High School in East Chicago, Indiana; and Patty Sheehan, a three-time state golf champion at Wooster High School in Reno, Nevada, in the early 1970s who later won 35 events on the Ladies Professional Golf Association (LPGA) tour. Sheehan is the first individual from Nevada to selected for the Hall of Fame. These former outstanding high school athletes, along with three coaches, one contest official, two administrators and two individuals in the fine arts field, will be inducted into the 23rd class of the National High School Hall of Fame July 2 at the Marriott Rivercenter in San Antonio, site of the National Federation of State High School Associations’ (NFHS) 86th annual Summer Meeting. -

All-Time All-America Teams

1944 2020 Special thanks to the nation’s Sports Information Directors and the College Football Hall of Fame The All-Time Team • Compiled by Ted Gangi and Josh Yonis FIRST TEAM (11) E 55 Jack Dugger Ohio State 6-3 210 Sr. Canton, Ohio 1944 E 86 Paul Walker Yale 6-3 208 Jr. Oak Park, Ill. T 71 John Ferraro USC 6-4 240 So. Maywood, Calif. HOF T 75 Don Whitmire Navy 5-11 215 Jr. Decatur, Ala. HOF G 96 Bill Hackett Ohio State 5-10 191 Jr. London, Ohio G 63 Joe Stanowicz Army 6-1 215 Sr. Hackettstown, N.J. C 54 Jack Tavener Indiana 6-0 200 Sr. Granville, Ohio HOF B 35 Doc Blanchard Army 6-0 205 So. Bishopville, S.C. HOF B 41 Glenn Davis Army 5-9 170 So. Claremont, Calif. HOF B 55 Bob Fenimore Oklahoma A&M 6-2 188 So. Woodward, Okla. HOF B 22 Les Horvath Ohio State 5-10 167 Sr. Parma, Ohio HOF SECOND TEAM (11) E 74 Frank Bauman Purdue 6-3 209 Sr. Harvey, Ill. E 27 Phil Tinsley Georgia Tech 6-1 198 Sr. Bessemer, Ala. T 77 Milan Lazetich Michigan 6-1 200 So. Anaconda, Mont. T 99 Bill Willis Ohio State 6-2 199 Sr. Columbus, Ohio HOF G 75 Ben Chase Navy 6-1 195 Jr. San Diego, Calif. G 56 Ralph Serpico Illinois 5-7 215 So. Melrose Park, Ill. C 12 Tex Warrington Auburn 6-2 210 Jr. Dover, Del. B 23 Frank Broyles Georgia Tech 6-1 185 Jr. -

2013 - 2014 Media Guide

2013 - 2014 MEDIA GUIDE www.bcsfootball.org The Coaches’ Trophy Each year the winner of the BCS National Champi- onship Game is presented with The Coaches’ Trophy in an on-field ceremony after the game. The current presenting sponsor of the trophy is Dr Pepper. The Coaches’ Trophy is a trademark and copyright image owned by the American Football Coaches As- sociation. It has been awarded to the top team in the Coaches’ Poll since 1986. The USA Today Coaches’ Poll is one of the elements in the BCS Standings. The Trophy — valued at $30,000 — features a foot- ball made of Waterford® Crystal and an ebony base. The winning institution retains The Trophy for perma- nent display on campus. Any portrayal of The Coaches’ Trophy must be li- censed through the AFCA and must clearly indicate the AFCA’s ownership of The Coaches’ Trophy. Specific licensing information and criteria and a his- tory of The Coaches’ Trophy are available at www.championlicensing.com. TABLE OF CONTENTS AFCA Football Coaches’ Trophy ............................................IFC Table of Contents .........................................................................1 BCS Media Contacts/Governance Groups ...............................2-3 Important Dates ...........................................................................4 The 2013-14 Bowl Championship Series ...............................5-11 The BCS Standings ....................................................................12 College Football Playoff .......................................................13-14