February Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download This List As PDF Here

QuadraphonicQuad Multichannel Engineers of 5.1 SACD, DVD-Audio and Blu-Ray Surround Discs JULY 2021 UPDATED 2021-7-16 Engineer Year Artist Title Format Notes 5.1 Production Live… Greetins From The Flow Dishwalla Services, State Abraham, Josh 2003 Staind 14 Shades of Grey DVD-A with Ryan Williams Acquah, Ebby Depeche Mode 101 Live SACD Ahern, Brian 2003 Emmylou Harris Producer’s Cut DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck David Alan David Alan DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Dire Straits Brothers In Arms DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Dire Straits Alchemy Live DVD/BD-V Ainlay, Chuck Everclear So Much for the Afterglow DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck George Strait One Step at a Time DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck George Strait Honkytonkville DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Sailing To Philadelphia DVD-A DualDisc Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Shangri La DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Mavericks, The Trampoline DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Olivia Newton John Back With a Heart DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Pacific Coast Highway Pacific Coast Highway DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Peter Frampton Frampton Comes Alive! DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Trisha Yearwood Where Your Road Leads DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Vince Gill High Lonesome Sound DTS CD/DVD-A/SACD Anderson, Jim Donna Byrne Licensed to Thrill SACD Anderson, Jim Jane Ira Bloom Sixteen Sunsets BD-A 2018 Grammy Winner: Anderson, Jim 2018 Jane Ira Bloom Early Americans BD-A Best Surround Album Wild Lines: Improvising on Emily Anderson, Jim 2020 Jane Ira Bloom DSD/DXD Download Dickinson Jazz Ambassadors/Sammy Anderson, Jim The Sammy Sessions BD-A Nestico Masur/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Kverndokk: Symphonic Dances BD-A Orchestra Anderson, Jim Patricia Barber Modern Cool BD-A SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2020 Patricia Barber Higher with Ulrike Schwarz Download SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2021 Patricia Barber Clique Download Svilvay/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Mortensen: Symphony Op. -

January 29, 1969 15 Cents Is Given

Judge's opinion cites public notice SAMPLE COPY Zoning ordinance validity to be tested The St. Johns city commission temporarily to provisions of an review of asuitby the city brought ness rezoned to allow construc by the city. However, according the proposed ordinance by city merely to resolve the issues sur learned Monday night that a zon earlier ordinance adopted in against Lawrence andJoyceKar- tion of additional facilities. Ac to Judge Bebau's statement, there residents. rounding actions evolving from ing ordinance currently being ad 1944. ber, doing business as Karber cording to the written decision by is reason to doubt the validity of Judge Bebau expliclty states in Karber's original request for hered to may be invalid and, Former City Attorney William Block & Tile Co. Judge Bebau, Karber applied for the present zoning ordinance be his statement that the decision in zoning redeslgnation. pending final judgment by Cir Kemper addressed the commis The action centered on Kar- a redesignatlon after the alleged cause of Improper public noti no way attempts to determine the cuit Court Judge Leo Bebau, the sion advising them of the opinion ber's desire to have sections of effective date of the current or fication of a hearing conducted to wisdom or desirability of the con According to City Attorney city may be forced to return rendered by JudgeBebau after his land near his block and tile busi dinance and was denied a change obtain objections or support of tents of the zoning ordinance, but Paul Maples a final judgment In the case has yet to be made and the city will have opportunity to appeal or to accept the judgment if it follows the initial decision. -

Sample Script

The Rocky Monster Show Junior Script by Malcolm Sircom 10/050619/23 ISBN: 978 1 89875 479 4 Published by Musicline Publications P.O. Box 15632 Tamworth Staffordshire B78 2DP 01827 281 431 www.musiclinedirect.com Licences are always required when published musicals are performed. Licences for musicals are only available from the publishers of those musicals. There is no other source. All our Performing, Copying & Video Licences are valid for one year from the date of issue. If you are recycling a previously performed musical, NEW LICENCES MUST BE PURCHASED to comply with Copyright law required by mandatory contractual obligations to the composer. Prices of Licences and Order Form can be found on our website: www.musiclinedirect.com The Rocky Monster Show (Junior) – Script 17 PROLOGUE After a very ‘Beginning of Time’ type musical introduction, the music changes to Rock. The Soloists come on, one by one, to sing their lines. The lines’ distribution can be at the Director’s discretion or it could be sung by all. The chorus can, if wished, be a permanent choir, set at the sides, or there can be a separate choir in addition. TRACK 1: EVOLUTION (SONG) 1: IN THE BEGINNING THERE WAS MIASMA... 2: AND A SOUPY SORT OF PLASMA... 3: AND FROM THIS PHANTAGASMA... ALL 3: THERE CAME LIFE! 4: AND WHILE ITS BED WAS HOT AND STEAMING... 5: WITH ITS BIRTH PANGS IT WAS SCREAMING... 6: THE PRIMEVAL SLIME WAS TEEMING... ALL 6: WITH LIFE! + CHORUS: EVOLUTION! EVOLUTION! IS IT JUST A CHEMICAL SOLUTION? CHANGE, MUTATE AND BLEND, MAKE AND MATCH AND MEND, WHERE’S IT GOING TO END? EVOLUTION! 7: THERE WERE AMOEBA STARTED BREATHING.. -

Tony Banks – a Chord Too

Tony Banks – A Chord Too Far (Box) (64:33/70:29/63:41/76:43, 4 CD- Boxset, Cherry Red Records, Esoteric Recordings, 2015) Neben dem Werk von Anthony Phillips nimmt sich Esoteric auch der Solo- Karriere des Genesis-Keyboarders und - Mitbegründers Tony Banks an. Nachdem 2009 sein inzwischen wieder vergriffenes Solo-Debut „A Curious Feeling“ im Nick Davis-5.1 Mix veröffentlicht wurde, legt man jetzt mit „A chord Too Far“ eine umfangreiche Retrospektive auf vier CDs vor. Tony Banks höchstselbst hat die Stücke für diese Compilation ausgesucht und teilt im Begleitbuch auch seine Gedanken dazu mit. Während er dort chronologisch vorgeht, sind die ausgewählten Titel auf den CDs bunt durcheinander gewürfelt. Die orchestral arrangierten Titel, die u.a. von seinen Soundtrack Projekten und Klassikalben stammen, sind allesamt auf der vierten CD versammelt – eine sinnvolle Trennung, um allzu große Stilbrüche zu vermeiden. Hört man sich nun durch „A Chord Too Far“ durch, begegnet man nicht nur der einen oder anderen bekannten Stimme (u.a. denen von Fish, Nik Kershaw, Toyah, Jim Diamond), sondern hört auch deutlich Banks´ Einfluss auf den Sound von Genesis heraus, insbesondere auch auf deren späte Entwicklung zur Pop/Rock- Stadionband. Wie bei Collins und Rutherford auch, tritt der progressive Rock dabei mehr und mehr in den Hintergrund, obwohl er bei Banks zumindest immer mal wieder unter dem Teppich hervor lugt. Bekanntermaßen ist Tony Banks´ Solo-Karriere im Vergleich zu seinen Kollegen weniger erfolgreich geblieben (auch wenn „A Curious Feeling“ glühende Fans hat, die Schlussred.). Möglicherweise lag es daran, dass er sich letztlich zwischen zu viele Stühle setzte und praktisch bei jedem Solo-Werk ein neues Konzept wählte, ohne dabei auch nur die Nähe eines konkreten eigenen Profils zu kommen. -

Daniel Keyes, Was First Released in October 1979 by Charisma Death Metal by EXHUMATION Deserves the Term "Classic." It Is Sinister, Clanging and Evil

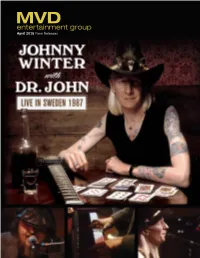

April 2016 New Releases what’s featured exclusives PAGE inside Music 3 RUSH Releases Available immediately! 47 DVD & Blu-ray Music Video DVD & Blu-ray 3 FEATURED RELEASES Non-Music Video DVD & Blu-ray 7 Vinyl JOHNNY WINTER WITH ANTIBALAS - THE ZERO BOYS Audio 19 DR. JOHN: LIVE IN... LIVE FROM THE HOUS... [BLU-RAY & DVD] Page 5 Page 4 Page 17 CD Audio 29 MVD Distribution Independent Releases 42 Order Form 52 Deletions and Price Changes 54 HAWKWIND - HASSAN I SKOLD - THE UNDOING SOUTHSIDE JOHNNY 800.888.0486 SAHBA B/WDAMNATION LIMITED EDITION LP AND THE ASBURY JUKES - ALLEY PART 2 Page 55 SOULTIME! 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 www.MVDb2b.com Page 26 Page 49 JOHNNY WINTER, WITH DR. JOHN MOTORHEAD - HELLFIRE: ANTIBALAS - LIVE FROM THE -LIVE IN SWEDEN 1987 RECORDEDIN RIO DE JANEIRO HOUSE OF SOUL MVD April forecast: Hot Winter in Sweden! 2011 Sweden gets melted by Winter, as in white-hot guitar slinger JOHNNY WINTER! Witness his axe- mastery in this 1987 show available on CD/DVD/LP. LIVE IN SWEDEN also features special guest DR. JOHN, accenting the show with his Nawlins spice. He may be the late Johnny Winter, but he was on-time and rockin’ this night! Woven into the fabric of rock and roll forever is another RIP, rock legend LEMMY KILMISTER and his infamous band MOTORHEAD. Lemmy lives large in the MOTORHEAD DVD HELLFIRE, recorded in Rio in 2011. As the outpouring of emotional tributes continue regarding DAVID BOWIE’s earthly departure, we offer two new Bowie CDs in April, one a 1983 broadcast with Stevie Ray Vaughan! Funk and Afro-Beat purveyors ANTIBALAS broadcast their sight and sound in the second installment of Daptone Records LIVE FROM THE HOUSE OF SOUL DVD series. -

Emerson Townshend

Simon Townshend Keith MAT2020 - No 0 June 2013 MAT2020 Emerson Bernardo Lanzetti Guy Davis Distorted Harmony Christopher Lee The Rocker MAT2020 is a Italian web magazine born in November last year, which tells stories of music. MAT 2020 - MusicArTeam speaks... MAT = MusicArTeam, a musical association recently es- [email protected] tablished. General Manager and Web Designer Angelo De Negri 2020 = is a year that corresponds to a deadline, a date of 1st Vice General Manager and Chief Editor Athos Enrile verification of the work done. 2nd Vice General Manager, Chief Editor and Webmaster Massimo ‘Max’ Pacini The topics and artists are very varied and so was born the Administration Marta Benedetti, Paolo ‘Revo’ Revello idea of a NUMBER ZERO in English. Web Journalists and Photographers: Corrado Canonici, Lorenza Daverio, Erica Elliot, Renzo De Let’s try, in hopes of finding interest also outside Italy. Grandi, Omer Messinger, Fabrizio Poggi, Davide Rossi, Riccardo Storti, Alberto Terrile In this issue there are many subjects, from Christopher Lee to ... Keith Emerson, Guy Davis, Simon Town- MAT2020 is a trademark of MusicArTeam. shend, Bernardo Lanzetti, Distorted Harmony and much more. And we hope you’ll enjoy MAT2020! 2 3 contents (click on the name to go to the requested page) Christopher Lee Distorted Harmony Smallcreeps Day Keith Emerson Unreal City Bernardo Lanzetti Guy Davis Betters Lucy Jordache David Jackson Simon Townshend Sonja Kristina Katie Cruel (Ita) 4 5 by CORRADO CANONICI hat would you do if you reach 91 year la who won the World Guitar Idol and is con- of age and had worked with quite lit- sidered in the rock world as “the next Carlos The cover of “TheThe cover Omens Of Death” W erally all the major movie director and ac- Santana”. -

Die 3-Cd Genesis- Anthologie 'R-Kive'

DIE 3-CD GENESIS- ANTHOLOGIE ‘R-KIVE’ VÖ: 03. Oktober 2014 Erstmals vereint: 37 der besten Songs von Genesis und aus den Solowerken der einzelnen Musiker Am 03. Oktober wird Virgin EMI / Universal Music Catalogue die drei CDs umfassende Genesis-Anthologie ‘R- Kive’ veröffentlichen. Das 37 Songs umfassende CD-Set, das 42 Schaffensjahre umfasst, dokumentiert die Bandgeschichte mit klassischen Arbeiten von Genesis und ausgewähltem Material aus den Solokarrieren von Tony Banks, Phil Collins, Peter Gabriel, Steve Hackett sowie Mike Rutherford / Mike + The Mechanics. Die Werke von Genesis und die aus der Band hervorgegangenen Soloprojekte sind im Laufe der Jahre zu einer mehr als bemerkenswerten Serie von Glanzleistungen angewachsen und haben es gemeinsam auf unglaubliche 14 Alben gebracht, die die Charts anführten, sowie zwei weitere Dutzend in den Top 10. Insgesamt wurden von Genesis und den Solowerken der Bandmusiker weltweit mehr als 300 Millionen Alben verkauft. ‘R-Kive’ enthält in chronologischer Reihenfolge die größten Hits von Genesis, darunter ‘Invisible Touch’, ‘Turn It On Again’, ‘Land of Confusion’ und ‘I Can’t Dance’. Dazu gesellen sich, in entsprechender Reihenfolge, Soloklassiker wie ‘The Living Years’ und ‘Over My Shoulder’ von Mike + The Mechanics, ‘In The Air Tonight’ von Collins und sein Duett mit Philip Bailey, ‘Easy Lover’, sowie Peter Gabriels ‘Solsbury Hill’. ‘R-Kive’ beginnt mit ‘The Knife’, einer neunminütigen Proto-Punk-Nummer, die bei den frühen Konzerten den krönenden Abschluss bildete und noch zu jener Zeit entstanden war, bevor Hackett und Collins zur Band stießen. Zu den insgesamt 22 Songs von Genesis ist jeder der fünf Musiker gleichberechtigt mit jeweils drei Songs seiner Solowerke vertreten. -

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project RONALD J. NEITZKE Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: December 1, 2006 Copyright 2009 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born and raised in Minnesota St. Thomas College; University of Minnesota; Johns Hopkins University (SAIS) Entered the Foreign Service in1971 State Department; FSI; Norwegian language training 1971-1972 Oslo, Norway; Consular Officer/Staff Aide 1972-1974 Environment NATO Relations Visa cases State Department; FSI: Serbo-Croatian language study 1974-1975 Belgrade, Yugoslavia; Consular Officer 1975-1978 Politics Ethnic groups Albanian Kosovars Tito Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) meetings Orthodox Church Environment Security US Ambassadors Embassy staff Soviets Kosovo Consular reporting Government Yugoslavia’s future State Department: FSI; Pilot Threshold Training Program 1978 1 Mid-level officer training Evaluation of Program State Department; Special Assistant to Director of Policy Planning 1978-1980 Tony Lake Operations Staff Priorities Policy Group Global Policy Message Carter Policies Response to Soviets High-level policy disputes Human Rights State’s Dissent Channel Boycott of 1980 Moscow Olympics Iran Cuba Johns Hopkins University (SAIS); Soviet and East European Studies 1980-1981 State Department; Country Director, Czechoslovakia & Albania 1981-1983 Nazi-looted gold Czech negotiations Czech harassment Nazi-looted Jewish property Albania Corfu Channel Case State Department; Special Assistant to the Counselor -

Rodger Coleman Sun Ra Sundays

SUN RA SUNDAYS by Rodger Coleman This is a compilation of blog entries about SUN RA authored by RODGER G. COLEMAN from 2008 to 2015 and posted at nuvoid.blogspot.com. Coleman's blog contains hundreds of posts on a myriad of music subjects; we've culled only the Ra content. We have added no commentary, preferring to let this writing speak for itself. The vast Sun Ra knowledge base covered in Coleman's posts remains vital and historically valid. Identifiable historic inaccuracies (generally based on best-available sources at the time) are neither corrected nor footnoted. These are the posts and responses as they were published online at the time—the verbatim historic record. All copyrights belong to Coleman and the authors of the comments and quoted sources. This chronicle was collected, formatted & edited by Irwin Chusid, with assistance from Kristen Pierce, in November 2018. It is sequenced chronologically. Some unintentional misspelling has been corrected; idiosyncratic spelling, abbreviations, and casual disregard of capitalization niceties (mostly in the comments) were left as written. Most dead links are omitted. Reader comments are highlighted in red (although salutations- only comments have been omitted). Graphic images and photos from the blog are not included. (For graphics, see SAM BYRD's complementary collection of Sun Ra Sundays posts; Byrd also arranged all entries in discographical order.) This content has been collected for preservation, research, and circulation. In some cases, recent findings have amplified, clarified, or superseded particular details or assertions. It would be interesting to crowd-source updates with new information that's come to light since these posts were published. -

Phonogram Polygram LP's 1970-1983

AUSTRALIAN RECORD LABELS PHONOGRAM - POLYGRAM LP’S 1970 to 1983 COMPILED BY MICHAEL DE LOOPER © BIG THREE PUBLICATIONS, JANUARY 2017 1 POLYDOR 2302 016 ISLE OF WIGHT JIMI HENDRIX POLYDOR 2302 018 HENDRIX IN THE WEST JIMI HENDRIX 1972 POLYDOR 2302 023 THE CRY OF LOVE JIMI HENDRIX 6.79 POLYDOR 2302 046 THESE FOOLISH THINGS BRYAN FERRY 8.85 POLYDOR 2302 059 LIZARD KING CRIMSON 10.80 POLYDOR 2302 060 ISLANDS KING CRIMSON POLYDOR 2302 061 LARKS TONGUE IN ASPIC KING CRIMSON POLYDOR 2302 065 STARLESS AND BIBLE BLACK KING CRIMSON POLYDOR 2302 066 RED KING CRIMSON 10.80 POLYDOR 2302 067 U.S.A. KING CRIMSON 10.80 POLYDOR 2302 106 FACE DANCES THE WHO 4.81 EG 2302 112 DISCIPLINE KING CRIMSON 10.81 POLYDOR 2302 127 THE FRIENDS OF MR CAIRO JON AND VANGELIS 5.82 VERVE 2304 024 THE VERY BEST OF STAN GETZ STAN GETZ VERVE 2304 057 THE BILL EVANS TRIO ‘LIVE’ IMPORT BILL EVANS TRIO 5.72 VERVE 2304 058 THE VERY BEST OF COUNT BASIE COUNT BASIE 6.72 VERVE 2304 062 THE VERY BEST OF OSCAR PETERSON OSCAR PETERSON 11.72 VERVE 2304 071 GETZ / GILBERTO STAN GETZ & JOAO GILBERTO 4.81 VERVE 2304 105 COMMUNICATIONS STAN GETZ 10.73 VERVE 2304 124 LADY SINGS THE BLUES BILLIE HOLIDAY 3.85 VERVE 2304 138 MUSIC FOR ZEN MEDITATION TONY SCOTT 10.81 VERVE 2304 145 ONLY VISITING THIS PLANET LARRY NORMAN 11.73 VERVE 2304 151 NIGHT TRAIN OSCAR PETERSON 2.81 VERVE 2304 153 THE CAT JIMMY SMITH 3.85 VERVE 2304 155 ELLA IN BERLIN ELLA FITZGERALD VERVE 2304 185 STAN GETZ & BILL EVANS IMPORT STAN GETZ, BILL EVANS 1.75 VERVE 2304 186 JOHNNY HODGES IMPORT JOHNNY HODGES 1.75 VERVE 2304 -

Genesis R-Kive Mp3, Flac, Wma

Genesis R-Kive mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: R-Kive Country: Japan Released: 2014 Style: Prog Rock, Pop Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1865 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1158 mb WMA version RAR size: 1736 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 415 Other Formats: MP4 FLAC MP1 AUD TTA WMA FLAC Tracklist 1-1 –Genesis The Knife 8:54 1-2 –Genesis The Musical Box 10:25 1-3 –Genesis Supper's Ready 23:04 1-4 –Genesis The Cinema Show 10:50 1-5 –Genesis I Know What I Like (In The Wardrobe) 4:09 1-6 –Genesis The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway 4:54 1-7 –Genesis Back In N.Y.C 5:39 1-8 –Genesis Carpet Crawlers 5:15 1-9 –Steve Hackett Ace Of Wands 5:24 2-1 –Genesis Ripples 8:04 2-2 –Genesis Afterglow 4:11 2-3 –Peter Gabriel Solsbury Hill 4:23 2-4 –Genesis Follow You Follow Me 4:00 2-5 –Tony Banks For A While 3:39 2-6 –Steve Hackett Every Day 6:11 2-7 –Peter Gabriel Biko 7:28 2-8 –Genesis Turn It On Again 3:51 2-9 –Phil Collins In The Air Tonight 5:30 2-10 –Genesis Abacab 7:01 2-11 –Genesis Mama 6:48 2-12 –Genesis That's All 4:25 2-13 –Phil Collins Easy Lover 5:02 2-14 –Mike + The Mechanics* Silent Running (On Dangerous Ground) 5:47 3-1 –Genesis Invisible Touch 3:29 3-2 –Genesis Land Of Confusion 4:46 3-3 –Genesis Tonight Tonight Tonight 8:52 3-4 –Mike + The Mechanics* The Living Years 5:24 3-5 –Tony Banks Red Day On Blue Street 5:49 3-6 –Genesis I Can't Dance 4:01 3-7 –Genesis No Son Of Mine 6:39 3-8 –Genesis Hold On My Heart 4:36 3-9 –Mike + The Mechanics* Over My Shoulder 3:35 3-10 –Genesis Calling All Stations 5:46 3-11 –Peter Gabriel Signal To Noise 7:32 3-12 –Phil Collins Wake Up Call 5:14 3-13 –Steve Hackett Nomads 4:39 3-14 –Tony Banks Siren 8:49 Companies, etc. -

University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation.