Organizing Cools the Planet Tools and Reflections to Navigate the Climate Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WEB KARAOKE EN-NL.Xlsx

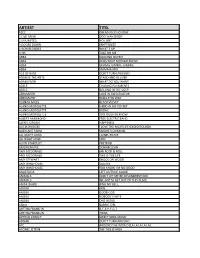

ARTIEST TITEL 10CC DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 2 LIVE CREW DOO WAH DIDDY 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 4 NON BLONDES WHAT´S UP A HA TAKE ON ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN ABBA DOES YOUR MOTHER KNOW ABBA GIMMIE GIMMIE GIMMIE ABBA MAMMA MIA ACE OF BASE DON´T TURN AROUND ADAM & THE ANTS STAND AND DELIVER ADAM FAITH WHAT DO YOU WANT ADELE CHASING PAVEMENTS ADELE ROLLING IN THE DEEP AEROSMITH LOVE IN AN ELEVATOR AEROSMITH WALK THIS WAY ALANAH MILES BLACK VELVET ALANIS MORISSETTE HAND IN MY POCKET ALANIS MORISSETTE IRONIC ALANIS MORISSETTE YOU OUGHTA KNOW ALBERT HAMMOND FREE ELECTRIC BAND ALEXIS JORDAN HAPPINESS ALICIA BRIDGES I LOVE THE NIGHTLIFE (DISCO ROUND) ALIEN ANT FARM SMOOTH CRIMINAL ALL NIGHT LONG LIONEL RICHIE ALL RIGHT NOW FREE ALVIN STARDUST PRETEND AMERICAN PIE DON MCLEAN AMY MCDONALD MR ROCK & ROLL AMY MCDONALD THIS IS THE LIFE AMY STEWART KNOCK ON WOOD AMY WINEHOUSE VALERIE AMY WINEHOUSE YOU KNOW I´M NO GOOD ANASTACIA LEFT OUTSIDE ALONE ANIMALS DON´T LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD ANIMALS WE GOTTA GET OUT OF THIS PLACE ANITA WARD RING MY BELL ANOUK GIRL ANOUK GOOD GOD ANOUK NOBODY´S WIFE ANOUK ONE WORD AQUA BARBIE GIRL ARETHA FRANKLIN R-E-S-P-E-C-T ARETHA FRANKLIN THINK ARTHUR CONLEY SWEET SOUL MUSIC ASWAD DON´T TURN AROUND ATC AROUND THE WORLD (LA LA LA LA LA) ATOMIC KITTEN THE TIDE IS HIGH ARTIEST TITEL ATOMIC KITTEN WHOLE AGAIN AVRIL LAVIGNE COMPLICATED AVRIL LAVIGNE SK8TER BOY B B KING & ERIC CLAPTON RIDING WITH THE KING B-52´S LOVE SHACK BACCARA YES SIR I CAN BOOGIE BACHMAN TURNER OVERDRIVE YOU AIN´T SEEN NOTHING YET BACKSTREET BOYS -

Billboard-1997-08-30

$6.95 (CAN.), £4.95 (U.K.), Y2,500 (JAPAN) $5.95 (U.S.), IN MUSIC NEWS BBXHCCVR *****xX 3 -DIGIT 908 ;90807GEE374EM0021 BLBD 595 001 032898 2 126 1212 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE APT A LONG BEACH CA 90807 Hall & Oates Return With New Push Records Set PAGE 1 2 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT AUGUST 30, 1997 ADVERTISEMENTS 4th -Qtr. Prospects Bright, WMG Assesses Its Future Though Challenges Remain Despite Setbacks, Daly Sees Turnaround BY CRAIG ROSEN be an up year, and I think we are on Retail, Labels Hopeful Indies See Better Sales, the right roll," he says. LOS ANGELES -Warner Music That sense of guarded optimism About New Releases But Returns Still High Group (WMG) co- chairman Bob Daly was reflected at the annual WEA NOT YOUR BY DON JEFFREY BY CHRIS MORRIS looks at 1997 as a transitional year for marketing managers meeting in late and DOUG REECE the company, July. When WEA TYPICAL LOS ANGELES -The consensus which has endured chairman /CEO NEW YORK- Record labels and among independent labels and distribu- a spate of negative m David Mount retailers are looking forward to this tors is that the worst is over as they look press in the last addressed atten- OPEN AND year's all- important fourth quarter forward to a good holiday season. But few years. Despite WARNER MUSI C GROUP INC. dees, the mood with reactions rang- some express con- a disappointing was not one of SHUT CASE. ing from excited to NEWS ANALYSIS cern about contin- second quarter that saw Warner panic or defeat, but clear -eyed vision cautiously opti- ued high returns Music's earnings drop 24% from last mixed with some frustration. -

Songs by Artist 08/29/21

Songs by Artist 09/24/21 As Sung By Song Title Track # Alexander’s Ragtime Band DK−M02−244 All Of Me PM−XK−10−08 Aloha ’Oe SC−2419−04 Alphabet Song KV−354−96 Amazing Grace DK−M02−722 KV−354−80 America (My Country, ’Tis Of Thee) ASK−PAT−01 America The Beautiful ASK−PAT−02 Anchors Aweigh ASK−PAT−03 Angelitos Negros {Spanish} MM−6166−13 Au Clair De La Lune {French} KV−355−68 Auld Lang Syne SC−2430−07 LP−203−A−01 DK−M02−260 THMX−01−03 Auprès De Ma Blonde {French} KV−355−79 Autumn Leaves SBI−G208−41 Baby Face LP−203−B−07 Beer Barrel Polka (Roll Out The Barrel) DK−3070−13 MM−6189−07 Beyond The Sunset DK−77−16 Bill Bailey, Won’t You Please Come Home? DK−M02−240 CB−5039−3−13 B−I−N−G−O CB−DEMO−12 Caisson Song ASK−PAT−05 Clementine DK−M02−234 Come Rain Or Come Shine SAVP−37−06 Cotton Fields DK−2034−04 Cry Like A Baby LAS−06−B−06 Crying In The Rain LAS−06−B−09 Danny Boy DK−M02−704 DK−70−16 CB−5039−2−15 Day By Day DK−77−13 Deep In The Heart Of Texas DK−M02−245 Dixie DK−2034−05 ASK−PAT−06 Do Your Ears Hang Low PM−XK−04−07 Down By The Riverside DK−3070−11 Down In My Heart CB−5039−2−06 Down In The Valley CB−5039−2−01 For He’s A Jolly Good Fellow CB−5039−2−07 Frère Jacques {English−French} CB−E9−30−01 Girl From Ipanema PM−XK−10−04 God Save The Queen KV−355−72 Green Grass Grows PM−XK−04−06 − 1 − Songs by Artist 09/24/21 As Sung By Song Title Track # Greensleeves DK−M02−235 KV−355−67 Happy Birthday To You DK−M02−706 CB−5039−2−03 SAVP−01−19 Happy Days Are Here Again CB−5039−1−01 Hava Nagilah {Hebrew−English} MM−6110−06 He’s Got The Whole World In His Hands -

JSR 2-2 E.Indd

Restoring the Garden of Eden in England’s Green and Pleasant Land: The Diggers and the Fruits of the Earth ■ Ariel Hessayon, Goldsmiths, University of London Th is Land which was barren and wast is now become fruitfull and pleasant like the Garden of Eden —Th e Kingdomes Faithful and Impartiall Scout1 I will not cease from Mental Fight, Nor shall my Sword sleep in my hand: Till we have built Jerusalem, In Englands green & pleasant Land —William Blake, ‘Preface’ to ‘Milton’2 I. The Diggers, 1649–50 On Sunday, 1 or perhaps 8 April 1649—it is difficult to establish the date with certainty—five people went to St. George’s Hill in the parish Walton-on- Th ames, Surrey, and began digging the earth. Th ey “sowed” the ground with parsnips, carrots, and beans, returning the next day in increased numbers. Th e following day they burned at least 40 roods of heath, which was considered “a very great prejudice” to the town. By the end of the week between 20 and 30 people were reportedly laboring the entire day at digging. It was said that they intended to plow up the ground and sow it with seed corn. Furthermore, they apparently threatened to pull down and level all park pales and “lay all open,” thereby evoking fears of an anti-enclosure riot (a familiar form Journal for the Study of Radicalism, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2008, pp. 1–25. issn 1930-1189. © Michigan State University. 1 2 Ariel Hessayon of agrarian protest).3 Th e acknowledged leaders of these “new Levellers” or “diggers” were William Everard (1602?–fl.1651) and Gerrard Winstanley (1609–76). -

I4P Rochdale Community Champions Building Community Knowledge, Developing Community Research

Rochdale Community Champions Building Community Knowledge, Developing Community Research in 2015 I4P Rochdale Community Champions Building Community Knowledge, Developing Community Research Rochdale Community Champions Building Community Knowledge, Developing Community Research Edited by Katy Goldstraw, Helen Chicot and John Diamond Contents 05 Foreword, Steve Rumbelow 06 Who Are Rochdale Community Champions? 07 The Leadership and Participatory Research Methods Training 08 Rochdale Community Champions: Adult and Continuing Education in action 09 Participatory Research: Principles and Practice 11 The Research: Case Studies 12 1. Yasmin and Andrew 29 2. Chris 32 3. Jan 39 4. Julia 45 5. Norma 45 The Research Process 48 Afterword, John Cater 49 Appendix One: Proposal from Edge Hill University to work with Rochdale Community Champions 51 Appendix Two - Four: Session Planners 53 Appendix Five: Who is Who and How to find out more 2 3 Rochdale Community Champions Building Community Knowledge, Developing Community Research Foreword to the Project Steve Rumbelow, Chief Executive, Rochdale Borough Council. This is the second booklet to come from the joint work between Edge Hill University and the Rochdale Borough Community Champions. It is an illustration of the deep thinking and hard work that our Community Champions put into their role; not just through the help they give to others as volunteers but also through the careful thought and care that sits behind that. This booklet provides us with some examples of what it means to be a Community Champion. It tells us that who you are and what you think and believe is an important element of what you do. Public services are facing very challenging times and are having to find new and better delivery models, which work to support confident and resilient communities. -

Razorcake Issue #25 As A

ot too long ago, I went to visit some relatives back in Radon, the Bassholes, or Teengenerate, during every spare moment of Alabama. At first, everybody just asked me how I was my time, even at 3 A.M., was often the only thing that made me feel N doing, how I liked it out in California, why I’m not mar- like I could make something positive out of my life and not just spend N it mopping floors. ried yet, that sort of thing. You know, just the usual small talk ques- tions that people feel compelled to ask, not because they’re really For a long time, records, particularly punk rock records, were my interested but because they’ll feel rude if they don’t. Later on in the only tether to any semblance of hope. Growing up, I was always out of day, my aunt started talking to me about Razorcake, and at one point place even among people who were sort of into the same things as me. she asked me if I got benefits. It’s probably a pretty lame thing to say, but sitting in my room listen- I figured that it was pretty safe to assume that she didn’t mean free ing to Dillinger Four or Panthro UK United 13 was probably the only records and the occasional pizza. “You mean like health insurance?” time that I ever felt like I wasn’t alone. “Yeah,” she said. “Paid vacation, sick days, all that stuff. But listening to music is kind of an abstract. -

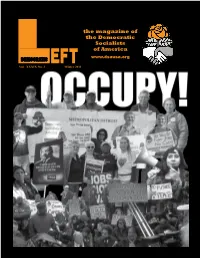

Download Issue (PDF)

the magazine of the Democratic Socialists of America DEMOCRATIC EFT www.dsausa.org Vol. XXXIX No. 3 Winter 2011 DSA’s 2011 convention: Building socialism, forming comradeship, resisting corporate domination By Michael Hirsch he hotel housing the convention was contemporary turnout contest just days Americana, a blue glass multi-story pile. As before the convention. And architecture and location, the area was capitalism then there was Occupy regnant, situated in a right-to-starve state where Wall Street’s exemplary Tunions are under the gun and socialism is a word used populist effort to speak for to scare the horses. No one was scared this time, as a disenfranchised majority, Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) held its 2011 fan the proverbial flames biennial convention and marked its tasks and perspectives of discontent and turn class at a time when resistance, emboldened by the Arab spring, war from a slur by the the Wisconsin mass demonstrations and the Occupy Wall right into a description of a Street movement’s confidence that “we are the 99 %” is compelling left politics. on the rise. If one thing crystallized Inside the capacious convention hall, under a scarlet the convention consensus, banner proclaiming “Obama is No Socialist, But We Are,” it was naming and targeting criminal mismanagement over 100 delegates and observers, including a far-right by the nation’s financial institutions, the laggard blogger from the misnamed Accuracy in Media, planned government response to the economic crisis, and their fightback for the New Year. Delegates savored resistance in the streets, on the job and ideologically the impact of the Wisconsin protests that built massive to free-market fundamentalism and the plutocrats who resistance to the state governor’s union busting, the huge benefit from it. -

Anarchists in the Late 1990S, Was Varied, Imaginative and Often Very Angry

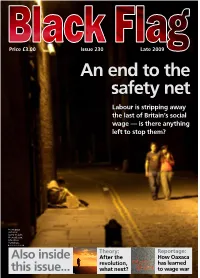

Price £3.00 Issue 230 Late 2009 An end to the safety net Labour is stripping away the last of Britain’s social wage — is there anything left to stop them? Front page pictures: Garry Knight, Photos8.com, Libertinus Yomango, Theory: Reportage: Also inside After the How Oaxaca revolution, has learned this issue... what next? to wage war Editorial Welcome to issue 230 of Black Flag, the fifth published by the current Editorial Collective. Since our re-launch in October 2007 feedback has generally tended to be positive. Black Flag continues to be published twice a year, and we are still aiming to become quarterly. However, this is easier said than done as we are a small group. So at this juncture, we make our usual appeal for articles, more bodies to get physically involved, and yes, financial donations would be more than welcome! This issue also coincides with the 25th anniversary of the Anarchist Bookfair – arguably the longest running and largest in the world? It is certainly the biggest date in the UK anarchist calendar. To celebrate the event we have included an article written by organisers past and present, which it is hoped will form the kernel of a general history of the event from its beginnings in the Autonomy Club. Well done and thank you to all those who have made this event possible over the years, we all have Walk this way: The Black Flag ladybird finds it can be hard going to balance trying many fond memories. to organise while keeping yourself safe – but it’s worth it. -

Refugee Crisis

DIOCESE OF LEEDS: JUSTICE AND PEACE COMMISSION NEWSLETTER - November 2015 Web www.leedsjp.org.uk mailto:[email protected] THE PARIS ATTACKS – A ‘BLOWBACK WAR’ The attacks in Paris on 13 November have generated enormous media coverage and outrage and sadness among so many people. The Commission does not have any answers – but in a spirit of encouraging people to look under the surface of the problems, here are a couple of places to start: (Let us know if you have other suggestions) Yorkshire’s own Paul Rogers (Professor in the Peace Studies Dept. at Bradford University) describes the attacks as a ‘blowback war’. The full article, on the Open Democracy website is worth a read: https://www.opendemocracy.net/paris-atrocity-and-after In the Guardian on 16 Nov there was a thoughtful piece by Scott Atran – which raises some question marks about the more hysterical rhetoric coming from some quarters of the media. http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/nov/15/terrorists-isis It’s also important to get these tragic events in perspective. This infographic from the Independent of a year ago gives a very different impression to what we see and read normally: Here is the link: http://i100.independent.co.uk/article/the-10-countries-where-terrorist-attacks- kill-the-most-people--ekK-zVZl_g REFUGEE CRISIS – ‘WELCOME THE STRANGER’ Our Lady of Kirkstall parish in NW Leeds is made up of 3 church communities: St.Mary’s Horsforth, Holy Name in Cookridge and the Assumption in West Park. Once a year they hold a whole parish celebration and the theme this year was “Welcome the Stranger”. -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

Direct Action #46 Spring 2009

Direct Action www.direct-action.org.uk Spring 2009 contents Direct Action is published by the Solidarity Federation, British sec- tion of the International Workers Inside this issue: Association (IWA). DA is edited and laid out by the DA Collective, and printed by 4: Beyond the Usual Union Structures Clydeside Press. 6: PFI: The Economics of the Madhouse Views stated in these pages are not necessarily those of the Direct 8: The Dead End of Nationalisation - how state owner- Action Collective or the Solidarity ship does not, never has, and never will serve our class Federation. We do not publish contributors’ 11: Breeding like Rats - the professional middle classes names. Please contact us if you under new labour want to know more. 12: The Crisis Factory - the roots of the global ecological Subscriptions crisis (for 4 issues ) 14: A Killer at Work / Have your Say - single status / Supporters – £10 g20 / sapphire Basic – £5 (Europe – £10; 16: 1976 and all that rest of the world – £15) 18: Looking back at the 1984-5 Miners’ Strike cheques payable to “Direct Action” – return to: 21: If Voting could Change the System... - the liber- DA, PO Box 29, S.W.D.O., tarian case for direct democracy Manchester, M15 5HW. 24: The Union or the Party To contribute 27: International - argentina / spain / germany / guadeloupe If you would like to help out or contribute articles or photos, work 28: Reviews - flat earth news / the dirty thirty / liberal fas is entirely voluntary. cism / the matthew herbert big band / the common place We welcome articles of between 31: Anarchism and Crime 250 and 1,500 words on industrial, social/community and international 35: Contacts Directory issues; on working class history; and on anarchist/anarcho- syndicalist theory and history. -

Authenticity, Politics and Post-Punk in Thatcherite Britain

‘Better Decide Which Side You’re On’: Authenticity, Politics and Post-Punk in Thatcherite Britain Doctor of Philosophy (Music) 2014 Joseph O’Connell Joseph O’Connell Acknowledgements Acknowledgements I could not have completed this work without the support and encouragement of my supervisor: Dr Sarah Hill. Alongside your valuable insights and academic expertise, you were also supportive and understanding of a range of personal milestones which took place during the project. I would also like to extend my thanks to other members of the School of Music faculty who offered valuable insight during my research: Dr Kenneth Gloag; Dr Amanda Villepastour; and Prof. David Wyn Jones. My completion of this project would have been impossible without the support of my parents: Denise Arkell and John O’Connell. Without your understanding and backing it would have taken another five years to finish (and nobody wanted that). I would also like to thank my daughter Cecilia for her input during the final twelve months of the project. I look forward to making up for the periods of time we were apart while you allowed me to complete this work. Finally, I would like to thank my wife: Anne-Marie. You were with me every step of the way and remained understanding, supportive and caring throughout. We have been through a lot together during the time it took to complete this thesis, and I am looking forward to many years of looking back and laughing about it all. i Joseph O’Connell Contents Table of Contents Introduction 4 I. Theorizing Politics and Popular Music 1.