Effectiveness of DNA Barcoding in Speyeria Butterflies at Small

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This File Was Created by Scanning the Printed

J Insect Behav DOl 10.1007/sI0905-011-9289-1 Evidence for Mate Guarding Behavior in the Taylor's Checkerspot Butterfly Victoria J. Bennett· Winston P. Smith· Matthew G. Betts Revised: 29 July 20 II/Accepted: 9 August 20II ��. Springer Seicnee+Business Media, LLC 2011 Abstract Discerning the intricacies of mating systems in butterflies can be difficult, particularly when multiple mating strategies are employed and are cryptic and not exclusive. We observed the behavior and habitat use of 113 male Taylor's checkerspot butterflies (Euphydryas editha taylori). We confinned that two distinct mating strategies were exhibited; patrolling and perching. These strategies varied temporally in relation to the protandrous mating system employed. Among perching males, we recorded high site fidelity and aggressive defense of small «5 m2) territories. This telTitoriality was not clearly a function of classic or non-classic resource defense (i.e., host plants or landscape), but rather appeared to constitute guarding of female pupae (virgin females). This discrete behavior is previously undocumented for this species and has rarely been observed in butterflies. Keywords Euphydryas editha taylori . mating systems · pre-copulatory mate guarding· protandry· sexual selection Introduction Inn'asexual selection is the most conunonly observed and well-documented sexual selection process exhibited by butterfly species (Andersson 1994; Rutowski 1997; Wiklund 2003). Competition between males for sexually receptive females has led to the evolution of a large variety of mating systems in this taxon (Rutowski 1991). Among these mating systems, mate acquisition strategies, such as mate locating, V J. Bennett (18) . M. G. Betts Department of Forest Ecosystems and Society, Oregon State University. -

Final Report on Valley Silverspot Butterfly (Speyeria Zerene Bremnerii) Surveys in the Suislaw National Forest and Salem District BLM

Final report on Valley silverspot butterfly (Speyeria zerene bremnerii) surveys in the Suislaw National Forest and Salem District BLM Assistance agreement L08AC13768, Modification 7 Mill Creek proposed ACEC, Polk County, OR. Photo by Alexa Carleton Field work, background research, and report completed by Alexa Carleton, Candace Fallon, and Sarah Foltz Jordan, The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation October 30, 2012 Table of Contents Summary ….…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…. 3 Introduction …….………………………………………………………………………………………….…………………….….… 3 Survey protocol …….………..…………………………………………………………………………………………………….… 4 Sites surveyed and survey results …..…….…………………………………………………………………………….…… 6 Northern Polk County sites (July 23) …………………………………………………………………………….. 6 Northern Benton County sites (July 24) ………………………………………………………………….….… 8 Southern Polk County sites (July 31) ………………………………………………………………………….. 11 Yamhill County sites (August 7)…………………………………………………………………………………… 12 Southern Benton County sites (August 12) ……………………………………………………………….… 13 Mary’s Peak, Benton County (August 15) ……………………………………………………….………..… 15 Potential future survey work…………….……………………………………………………………………………………. 20 Acknowledgments …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 22 References .…………….……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 22 Appendix I: Historic records of S. z. bremnerii in Oregon………………………………………………………... 23 Appendix II: Summary table of sites surveyed …….…………………………………………………………………. 27 Appendix III: Maps of sites surveyed ………………………………………………………..………………………….… -

Philmont Butterflies

PHILMONT AREA BUTTERFLIES Mexican Yellow (Eurema mexicana) Melissa Blue (Lycaeides melissa) Sleepy Orange (Eurema nicippe) Greenish Blue (Plebejus saepiolus) PAPILIONIDAE – Swallowtails Dainty Sulfur (Nathalis iole) Boisduval’s Blue (Icaricia icarioides) Subfamily Parnassiinae – Parnassians Lupine Blue (Icaricia lupini) Rocky Mountain Parnassian (Parnassius LYCAENIDAE – Gossamer-wings smintheus) Subfamily Lycaeninae – Coppers RIODINIDAE – Metalmarks Tailed Copper (Lycaena arota) Mormon Metalmark (Apodemia morma) Subfamily Papilioninae – Swallowtails American Copper (Lycaena phlaeas) Nais Metalmark (Apodemia nais) Black Swallowtail (Papilio polyxenes) Lustrous Copper (Lycaena cupreus) Old World Swallowtail (Papilio machaon) Bronze Copper (Lycaena hyllus) NYMPHALIDAE – Brush-footed Butterflies Anise Swallowtail (Papilio zelicaon) Ruddy Copper (Lycaena rubidus) Subfamily Libytheinae – Snout Butterflies Western Tiger Swallowtail (Papilio rutulus) Blue Copper (Lycaena heteronea) American Snout (Libytheana carinenta) Pale Swallowtail (Papilio eurymedon) Purplish Copper (Lycaena helloides) Two-tailed Swallowtail (Papilio multicaudatus) Subfamily Heliconiinae – Long-wings Subfamily Theclinae – Hairstreaks Gulf Fritillary (Agraulis vanillae) PIERIDAE – Whites & Sulfurs Colorado Hairstreak (Hypaurotis crysalus) Subfamily Pierinae – Whites Great Purple Hairstreak (Atlides halesus) Subfamily Argynninae – Fritillaries Pine White (Neophasia menapia) Southern Hairstreak (Fixsenia favonius) Variegated Fritillary (Euptoieta claudia) Becker’s White (Pontia -

A Rearing Method for Argynnis (Speyeria) Diana

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Psyche Volume 2011, Article ID 940280, 6 pages doi:10.1155/2011/940280 Research Article ARearingMethodforArgynnis (Speyeria) diana (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) That Avoids Larval Diapause Carrie N. Wells, Lindsey Edwards, Russell Hawkins, Lindsey Smith, and David Tonkyn Department of Biological Sciences, Clemson University, 132 Long Hall, Clemson, SC 29634, USA Correspondence should be addressed to Carrie N. Wells, [email protected] Received 25 May 2011; Accepted 4 August 2011 Academic Editor: Russell Jurenka Copyright © 2011 Carrie N. Wells et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. We describe a rearing protocol that allowed us to raise the threatened butterfly, Argynnis diana (Nymphalidae), while bypassing the first instar overwintering diapause. We compared the survival of offspring reared under this protocol from field-collected A. diana females from North Carolina, Georgia, and Tennessee. Larvae were reared in the lab on three phylogenetically distinct species of Southern Appalachian violets (Viola sororia, V. pubescens,andV. pedata). We assessed larval survival in A. diana to the last instar, pupation, and adulthood. Males reared in captivity emerged significantly earlier than females. An ANOVA revealed no evidence of host plant preference by A. diana toward three native violet species. We suggest that restoration of A. diana habitat which promotes a wide array of larval and adult host plants, is urgently needed to conserve this imperiled species into the future. 1. Introduction larvae in cold storage blocks and storing them under con- trolled refrigerated conditions for the duration of their The Diana fritillary, Argynnis (Speyeria) diana (Cramer overwintering period [10]. -

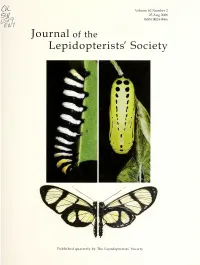

Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society

J OURNAL OF T HE L EPIDOPTERISTS’ S OCIETY Volume 62 2008 Number 2 Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society 61(2), 2007, 61–66 COMPARATIVE STUDIES ON THE IMMATURE STAGES AND DEVELOPMENTAL BIOLOGY OF FIVE ARGYNNIS SPP. (SUBGENUS SPEYERIA) (NYMPHALIDAE) FROM WASHINGTON DAVID G. JAMES Department of Entomology, Washington State University, Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center, 24105 North Bunn Road, Prosser, Washington 99350; email: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Comparative illustrations and notes on morphology and biology are provided on the immature stages of five Arg- ynnis spp. (A. cybele leto, A. coronis simaetha, A. zerene picta, A. egleis mcdunnoughi, A. hydaspe rhodope) found in the Pacific Northwest. High quality images allowed separation of the five species in most of their immature stages. Sixth instars of all species possessed a fleshy, eversible osmeterium-like gland located ventrally between the head and first thoracic segment. Dormant first in- star larvae of all species exposed to summer-like conditions (25 ± 0.5º C and continuous illumination), 2.0–2.5 months after hatch- ing, did not feed and died within 6–9 days, indicating the larvae were in diapause. Overwintering of first instars for ~ 80 days in dark- ness at 5 ± 0.5º C, 75 ± 5% r.h. resulted in minimal mortality. Subsequent exposure to summer-like conditions (25 ± 0.5º C and continuous illumination) resulted in breaking of dormancy and commencement of feeding in all species within 2–5 days. Durations of individual instars and complete post-larval feeding development durations were similar for A. coronis, A. zerene, A. egleis and A. -

Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society

Volume 62 Number 2 25 Aug 2008 ISSN 0024-0966 Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society Published quarterly by The Lepidopterists' Society ) ) THE LEPIDOPTERISTS’ SOCIETY Executive Council John H. Acorn, President John Lill, Vice President William E. Conner, Immediate Past President David D. Lavvrie, Secretary Andre V.L. Freitas, Vice President Kelly M. Richers, Treasurer Akito Kayvahara, Vice President Members at large: Kim Garwood Richard A. Anderson Michelle DaCosta Kenn Kaufman John V. Calhoun John H. Masters Plarry Zirlin Amanda Roe Michael G. Pogue Editorial Board John W. Rrovvn {Chair) Michael E. Toliver Member at large ( , Brian Scholtens (Journal Lawrence F. Gall ( Memoirs ) 13 ale Clark {News) John A. Snyder {Website) Honorary Life Members of the Society Charles L. Remington (1966), E. G. Munroe (1973), Ian F. B. Common (1987), Lincoln P Brower (1990), Frederick H. Rindge (1997), Ronald W. Hodges (2004) The object of The Lepidopterists’ Society, which was formed in May 1947 and formally constituted in December 1950, is “to pro- mote the science of lepidopterology in all its branches, ... to issue a periodical and other publications on Lepidoptera, to facilitate the exchange of specimens and ideas by both the professional worker and the amateur in the field; to secure cooperation in all mea- sures” directed towards these aims. Membership in the Society is open to all persons interested in the study of Lepidoptera. All members receive the Journal and the News of The Lepidopterists’ Society. Prospective members should send to the Assistant Treasurer full dues for the current year, to- gether with their lull name, address, and special lepidopterological interests. -

MOTHS and BUTTERFLIES LEPIDOPTERA DISTRIBUTION DATA SOURCES (LEPIDOPTERA) * Detailed Distributional Information Has Been J.D

MOTHS AND BUTTERFLIES LEPIDOPTERA DISTRIBUTION DATA SOURCES (LEPIDOPTERA) * Detailed distributional information has been J.D. Lafontaine published for only a few groups of Lepidoptera in western Biological Resources Program, Agriculture and Agri-food Canada. Scott (1986) gives good distribution maps for Canada butterflies in North America but these are generalized shade Central Experimental Farm Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0C6 maps that give no detail within the Montane Cordillera Ecozone. A series of memoirs on the Inchworms (family and Geometridae) of Canada by McGuffin (1967, 1972, 1977, 1981, 1987) and Bolte (1990) cover about 3/4 of the Canadian J.T. Troubridge fauna and include dot maps for most species. A long term project on the “Forest Lepidoptera of Canada” resulted in a Pacific Agri-Food Research Centre (Agassiz) four volume series on Lepidoptera that feed on trees in Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Canada and these also give dot maps for most species Box 1000, Agassiz, B.C. V0M 1A0 (McGugan, 1958; Prentice, 1962, 1963, 1965). Dot maps for three groups of Cutworm Moths (Family Noctuidae): the subfamily Plusiinae (Lafontaine and Poole, 1991), the subfamilies Cuculliinae and Psaphidinae (Poole, 1995), and ABSTRACT the tribe Noctuini (subfamily Noctuinae) (Lafontaine, 1998) have also been published. Most fascicles in The Moths of The Montane Cordillera Ecozone of British Columbia America North of Mexico series (e.g. Ferguson, 1971-72, and southwestern Alberta supports a diverse fauna with over 1978; Franclemont, 1973; Hodges, 1971, 1986; Lafontaine, 2,000 species of butterflies and moths (Order Lepidoptera) 1987; Munroe, 1972-74, 1976; Neunzig, 1986, 1990, 1997) recorded to date. -

Wildland Fire in Ecosystems: Effects of Fire on Fauna

United States Department of Agriculture Wildland Fire in Forest Service Rocky Mountain Ecosystems Research Station General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-42- volume 1 Effects of Fire on Fauna January 2000 Abstract _____________________________________ Smith, Jane Kapler, ed. 2000. Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on fauna. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 1. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 83 p. Fires affect animals mainly through effects on their habitat. Fires often cause short-term increases in wildlife foods that contribute to increases in populations of some animals. These increases are moderated by the animals’ ability to thrive in the altered, often simplified, structure of the postfire environment. The extent of fire effects on animal communities generally depends on the extent of change in habitat structure and species composition caused by fire. Stand-replacement fires usually cause greater changes in the faunal communities of forests than in those of grasslands. Within forests, stand- replacement fires usually alter the animal community more dramatically than understory fires. Animal species are adapted to survive the pattern of fire frequency, season, size, severity, and uniformity that characterized their habitat in presettlement times. When fire frequency increases or decreases substantially or fire severity changes from presettlement patterns, habitat for many animal species declines. Keywords: fire effects, fire management, fire regime, habitat, succession, wildlife The volumes in “The Rainbow Series” will be published during the year 2000. To order, check the box or boxes below, fill in the address form, and send to the mailing address listed below. -

Searching for Oregon Silverspot Butterfly (Speyeria Zerene Hippolyta

Use of Canines to Detect Early Life History Stages of a Threatened Butterfly Cody Burkhart Rich Van Buskirk Environmental Science Pacific University Extinction Rates Ceballos et al., 2015 Taxonomic Bias • International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) • Endangered Species Act (ESA) • Documenting insect extinctions are currently underrepresented (Dunn, 2005) 500 450 400 350 300 250 200 Number ofSpecies Number Insects 150 100 50 0 Vertebrates Invertebrates Mammals Birds Reptiles Amphibians Fishes Clams Snails Insects Arachnids Crustaceans Corals U.S Fish and Wildlife Service, 2017 Causes of Decline 90 80 70 60 50 40 Percentage 30 20 10 0 Resource Use Exotic Species Construction Altered Habitat Agriculture Species Pollution Water Dynamics Interactions Diversions (non-exotics) Lawler et al., 2002 Insect Conservation: Large Blue Butterfly (Maculinea arion) Photo By: PJC&CO from Wikimedia Commons Large Blue Butterfly • Early responses focused on habitat restoration • Critical life history stage relied on Myrmica sabuleti ants • Extirpated in the UK in 1979 Conservation Implications • Species decline can be reversible • Understanding life history is essential Oregon Silverspot Butterfly (Speyeria zerene hippolyta) • OSB Habitat: – Early successional communities – Salt-spray meadows – Oregon Coast and northern California coast. – Extirpated in Washington. • Larval host plant: early blue violet (Viola adunca) (Oregon Zoo 2009) History of Decline • Habitat loss U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2001 Remaining Threats • Succession 6000 • Invasive species 5000 4000 3000 Cascade Head Rock Creek Mount Hebo 2000 Oregon Silverspot Butterfly Population Numbers Population Butterfly Silverspot Oregon 1000 0 Year OSB Life Cycle Oregon Zoo, 2009 The Conservation Canines Project • Determine feasibility of using scent detection dogs to locate cryptic life history stages • Assess dynamics of pilot search project Mt. -

2010 Butterfly Inventories in Boulder County Open Space Properties

2010 Butterfly Inventories In Boulder County Open Space Properties By Janet Chu October 2, 2010 1 Table of Contents I. Acknowledgments …………………… 3 II. Abstract …………………………… 4 II. Introduction……………………………… 5 IV. Objectives ………………………….. 6 V. Research Methods ………………….. 7 VI. Results and Discussion ………………... 8 VII. Weather ………………………………… 12 VIII. Conclusions …………………………….. 13 VIII. Recommendations …………………….. 15 IX. References …………………………. 16 X. Butterfly Survey Data Tables …………. 17 Table I. Survey Dates and Locations ……………. 17 Table II. Southeast Buffer …………………. 18 Table III. Anne U. White – Fourmile Trail …… 21 Table IV. Heil Valley Open Space –Geer Watershed... 24 Table V. Heil Valley Open Space –Plumely Canyon 27 Table VI. Heil Valley Open Space – North ………… 30 Table VII. Walker Ranch - Meyer’s Gulch ………… 34 Table VIII. Caribou Ranch Open Space ……………… 37 Table IX. Compilation of Species and Locations …… 38 2 I. Acknowledgments Our research team has conducted butterfly surveys for nine consecutive years, from 2002 through 2010, with 2002-2004 introductory to the lands and species, and 2005-2010 in more depth. My valuable field team this year was composed of friends with sharp eyes and ready binoculars Larry Crowley who recorded not only the butterflies but blossoming plants and wildlife joined by Jean Morgan and Amy Chu both joined enthusiastic butterfly chasers. Venice Kelley and John Barr, professional photographers, joined us on many surveys. With their digital photos we are often able to classify the hard-to-identify butterflies later on at the desk. The surveys have been within Boulder County Parks and Open Space (BCPOS) lands. Therese Glowacki, Manager-Resource Manager, issued a Special Collection Permit for access into the Open Spaces; Susan Spaulding, Wildlife Specialist, oversaw research, maintained records of our monographs and organized seminars for presentation of data. -

Papilio (New Series) # 25 2016 Issn 2372-9449

PAPILIO (NEW SERIES) # 25 2016 ISSN 2372-9449 ERNEST J. OSLAR, 1858-1944: HIS TRAVEL AND COLLECTION ITINERARY, AND HIS BUTTERFLIES by James A. Scott, Ph.D. in entomology University of California Berkeley, 1972 (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract. Ernest John Oslar collected more than 50,000 butterflies and moths and other insects and sold them to many taxonomists and museums throughout the world. This paper attempts to determine his travels in America to collect those specimens, by using data from labeled specimens (most in his remaining collection but some from published papers) plus information from correspondence etc. and a few small field diaries preserved by his descendants. The butterfly specimens and their localities/dates in his collection in the C. P. Gillette Museum (Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado) are detailed. This information will help determine the possible collection locations of Oslar specimens that lack accurate collection data. Many more biographical details of Oslar are revealed, and the 26 insects named for Oslar are detailed. Introduction The last collection of Ernest J. Oslar, ~2159 papered butterfly specimens and several moths, was found in the C. P. Gillette Museum, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado by Paul A. Opler, providing the opportunity to study his travels and collections. Scott & Fisher (2014) documented specimens sent by Ernest J. Oslar of about 100 Argynnis (Speyeria) nokomis nokomis Edwards labeled from the San Juan Mts. and Hall Valley of Colorado, which were collected by Wilmatte Cockerell at Beulah New Mexico, and documented Oslar’s specimens of Oeneis alberta oslari Skinner labeled from Deer Creek Canyon, [Jefferson County] Colorado, September 25, 1909, which were collected in South Park, Park Co. -

Preliminary Insect (Butterfly) Survey at Griffith Park, Los Angeles, California

Kathy Keane October 30, 2003 Keane Biological Consulting 5546 Parkcrest Street Long Beach, CA 90808 Subject: Preliminary Insect (Butterfly) Survey at Griffith Park, Los Angeles, California. Dear Kathy: Introduction At the request of Keane Biological Consulting (KBC), Guy P. Bruyea (GPB) conducted a reconnaissance-level survey for the butterfly and insect inhabitants of Griffith Park in northwestern Los Angeles County, California. This report presents findings of our survey conducted to assess butterfly and other insect diversity within Griffith Park, and briefly describes the vegetation, topography, and present land use throughout the survey area in an effort to assess the overall quality of the habitat currently present. Additionally, this report describes the butterfly species observed or detected, and identifies butterfly species with potential for occurrence that were not detected during the present survey. All observations were made by GPB during two visits to Griffith Park in June and July 2003. Site Description Griffith Park is generally located at the east end of the Santa Monica Mountains northwest of the City of Los Angeles within Los Angeles County, California. The ± 4100-acre Griffith Park is situated within extensive commercial and residential developments associated with the City of Los Angeles and surrounding areas, and is the largest municipal park and urban wilderness area within the United States. Specifically, Griffith Park is bounded as follows: to the east by the Golden State Freeway (Interstate Highway 5) and the