Diagnostic Yield of Specific Inhalation Challenge in Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis: Challenges in Diagnosis and Management, Avoiding Surgical Lung Biopsy

395 Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis: Challenges in Diagnosis and Management, Avoiding Surgical Lung Biopsy Ferran Morell, MD1,2 Ana Villar, MD2,3 Iñigo Ojanguren, MD2,3 Xavier Muñoz, MD2,3 María-Jesús Cruz, PhD2,3 1 Vall d’Hebron Institut de Recerca (VHIR), Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain Address for correspondence Ferran Morell, MD, Vall d’Hebron Institut 2 Ciber de Enfermedades Respiratorias (CIBERES), Barcelona, Spain de Recerca (VHIR), PasseigValld’Hebron, 119-129, 08035 Barcelona, 3 Servei de Pneumologia, Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron, Catalonia, Spain (e-mail: [email protected]). Barcelona, Spain Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2016;37:395–405. Abstract This review presents an update of the currently available information related to Keywords hypersensitivity pneumonitis, with a particular focus on the contribution of several ► hypersensitivity techniques in the diagnosis of this condition. The methods discussed include proper pneumonitis elaboration of a complete medical history, targeted auscultation, detection of specific ► bronchoalveolar immunoglobulin G antibodies against the most common antigens causing this disease, lavage skin tests, antigen-specific lymphocyte activation assays, bronchoalveolar lavage, and ► fi speci c inhalation cryobiopsy. Special emphasis is placed on the relevant contribution of specificinhalation challenge challenge (bronchial challenge test). Surgical lung biopsy is presented as the ultimate ► bronchial challenge recourse, to be used when the diagnosis cannot be reached through the other methods test covered. -

Nebulizers: Diagnosis Codes – Medicare Advantage Policy Appendix

UnitedHealthcare® Medicare Advantage Policy Appendix: Applicable Code List Nebulizers: Diagnosis Codes This list of codes applies to the Medicare Advantage Policy Guideline titled Approval Date: September 8, 2021 Nebulizers. Applicable Codes The following list(s) of procedure and/or diagnosis codes is provided for reference purposes only and may not be all inclusive. The listing of a code does not imply that the service described by the code is a covered or non-covered health service. Benefit coverage for health services is determined by the member specific benefit plan document and applicable laws that may require coverage for a specific service. The inclusion of a code does not imply any right to reimbursement or guarantee claim payment. Other Policies and Guidelines may apply. Diagnosis Code Description For HCPCS Codes A7003, A7004, and E0570 A15.0 Tuberculosis of lung A22.1 Pulmonary anthrax A37.01 Whooping cough due to Bordetella pertussis with pneumonia A37.11 Whooping cough due to Bordetella parapertussis with pneumonia A37.81 Whooping cough due to other Bordetella species with pneumonia A37.91 Whooping cough, unspecified species with pneumonia A48.1 Legionnaires' disease B20 Human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] disease B25.0 Cytomegaloviral pneumonitis B44.0 Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis B59 Pneumocystosis B77.81 Ascariasis pneumonia E84.0 Cystic fibrosis with pulmonary manifestations J09.X1 Influenza due to identified novel influenza A virus with pneumonia J09.X2 Influenza due to identified novel influenza A virus with other -

Diapositivo 1

A.C. Nunes1, A. Domingues1, M. Almeida-Silva1,2, S. Viegas2, C. Viegas2 1 Escola Superior de Tecnologia e Saúde de Lisboa, Instituto Politécnico de Lisboa 2 Instituto Tecnológico e Nuclear, Instituto Superior Técnico, Universidade Técnica de Lisboa. Cork is a light, porous, impermeable material extracted from the bark of some trees. The most widely used cork is obtained from the cork tree Health Effects (Quercus suber). It is estimated that the area occupied by cork oaks in the Iberian Peninsula is around 33% in Portugal and 23% in Spain [1]. The studied articles refer two major diseases associated with this Portugal is the largest cork producing country in the world, followed by occupational setting, occupational asthma and Suberosis. Spain, and its industry is an important economical resource [2].The Occupational asthma is a disease whose origin is related to the processes used in the manufacture of cork depend on the end product to be obtained, being the production of stoppers for wine bottles the exposure to a particular factor in a workplace. Recent studies have main application. Most of the cork is stored under dark humid and identified Chrysonilia sitophila as a cause for this occupational disease moldy conditions. During the manufacturing process, workers are in the cork and logging industry [4, 5]. This fungi is a common mould exposed to an environment that is heavily contaminated with cork dust found in cork samples analyzed [6]. [3]. Due to this repeated exposure to moldy cork dust, cork workers are at risk for developing occupational lung diseases such as occupational Suberosis is the term applied to hypersensitivity pneumonitis due to asthma and Suberosis. -

Occupational Lung Diseases

Occupational Lung diseases Dr Deepak Aggarwal Dept. Of Pulmonary Medicine To be discussed…. • Pneumoconiosis • Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis PNEUMOCONIOSIS Pneumoconioses are pulmonary diseases caused by mineral dust inhalation in workplace The specific types of pneumoconioses are named by the substance inhaled (e.g., silicosis, asbestosis, anthracosis) PNEUMOCONIOSIS Mineral Dust‐Induced Lung Disease Coal dust Simple coal workers' pneumoconiosis: Coal mining macules and nodules Complicated coal workers' pneumoconiosis: PMF Silica Silicosis Sandblasting, quarrying, mining, stone cutting, foundry work, ceramics Asbestos Asbestosis pleural effusions, pleural plaques, or Mining, milling, diffuse fibrosis; mesothelioma; carcinoma of the and fabrication of ores and lung and larynx materials; installation and removal of insulation Fibrogenic pneumoconioses "true pneumoconioses" • asbestosis • berylliosis • • silicosis talcosis • kaolin pneumoconiosis. • hard metal disease • coal workers' • aluminum fibrosis, pneumoconiosis Shaver's disease Non‐fibrogenic pneumoconioses benign pneumoconioses Causes: • antimony • iron • barium • tin • boric acid • titanium • manganese • bismuth PNEUMOCONIOSIS Pathogenesis The development of a pneumoconiosis depends on (1) the amount of dust retained in the lung and airways (2) the size, shape, and buoyancy of the particles (3) solubility and physiochemical reactivity (4) the possible additional effects of other irritants (e.g., concomitant tobacco smoking) PNEUMOCONIOSIS Pathogenesis (1)The amount of dust retained -

336 Naegeli's

336 INDEX N Naegeli's Narrowing - continued - disease 287.1 - artery NEC - continued - leukemia, monocytic (M9863/3) 205.1 -- cerebellar 433.8 Naffziger's syndrome 353.0 -- choroidal 433.8 Naga sore (see also Ulcer, skin) 707.9 -- communicative posterior 433.8 Nagele's pelvis 738.6 -- coronary 414.0 - with disproportion 653.0 --- congenital 090.5 -- causing obstructed labor 660.1 --- due to syphilis 093.8 -- fetus or newborn 763.1 -- hypophyseal 433.8 Nail - see also condition -- pontine 433.8 - biting 307.9 -- precerebral NEC 433.9 - patella syndrome 756.8 --- multiple or bilateral 433.3 Nanism, nanosomia (see also Dwarfism) -- vertebral 433.2 259.4 --- with other precerebral artery 433.3 - pituitary 253.3 --- bilateral 433.3 - renis, renalis 588.0 auditory canal (external) 380.5 Nanukayami 100.8 cerebral arteries 437.0 Napkin rash 691.0 cicatricial - see Cicatrix Narcissism 302.8 eustachian tube 381.6 Narcolepsy 347 eyelid 374.4 Narcosis - intervertebral disc or space NEC - see - carbon dioxide (respiratory) 786.0 Degeneration, intervertebral disc - due to drug - joint space, hip 719.8 -- correct substance properly - larynx 478.7 administered 780.0 mesenteric artery (with gangrene) 557.0 -- overdose or wrong substance given or - palate 524.8 taken 977.9 - palpebral fissure 374.4 --- specified drug - see Table of drugs - retinal artery 362.1 and chemicals - ureter 593.3 Narcotism (chronic) (see also Dependence) - urethra (see also Stricture, urethra) 598.9 304.9 Narrowness, abnormal. eyelid 743.6 - acute NEC Nasal- see condition correct -

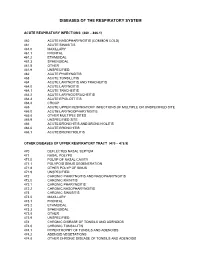

Diagnostic Code Descriptions (ICD9) Respiratory System

DISEASES OF THE RESPIRATORY SYSTEM ACUTE RESPIRATORY INFECTIONS (460 – 466.1) 460 ACUTE NASOPHARYNGITIS (COMMON COLD) 461 ACUTE SINUSITIS 461.0 MAXILLARY 461.1 FRONTAL 461.2 ETHMOIDAL 461.3 SPHENOIDAL 461.8 OTHER 461.9 UNSPECIFIED 462 ACUTE PHARYNGITIS 463 ACUTE TONSILLITIS 464 ACUTE LARYNGITIS AND TRACHEITIS 464.0 ACUTE LARYNGITIS 464.1 ACUTE TRACHEITIS 464.2 ACUTE LARYNGOTRACHEITIS 464.3 ACUTE EPIGLOTTITIS 464.4 CROUP 465 ACUTE UPPER RESPIRATORY INFECTIONS OF MULTIPLE OR UNSPECIFIED SITE 465.0 ACUTE LARYNGOPHARYNGITIS 465.8 OTHER MULTIPLE SITES 465.9 UNSPECIFIED SITE 466 ACUTE BRONCHITIS AND BRONCHIOLITIS 466.0 ACUTE BRONCHITIS 466.1 ACUTE BRONCHIOLITIS OTHER DISEASES OF UPPER RESPIRATORY TRACT (470 – 478.9) 470 DEFLECTED NASAL SEPTUM 471 NASAL POLYPS 471.0 POLYP OF NASAL CAVITY 471.1 POLYPOID SINUS DEGENERATION 471.8 OTHER POLYP OF SINUS 471.9 UNSPECIFIED 472 CHRONIC PHARYNGITIS AND NASOPHARYNGITIS 472.0 CHRONIC RHINITIS 472.1 CHRONIC PHARYNGITIS 472.2 CHRONIC NASOPHARYNGITIS 473 CHRONIC SINUSITIS 473.0 MAXILLARY 473.1 FRONTAL 473.2 ETHMOIDAL 473.3 SPHENOIDAL 473.8 OTHER 473.9 UNSPECIFIED 474 CHRONIC DISEASE OF TONSILS AND ADENOIDS 474.0 CHRONIC TONSILLITIS 474.1 HYPERTROPHY OF TONSILS AND ADENOIDS 474.2 ADENOID VEGETATIONS 474.8 OTHER CHRONIC DISEASE OF TONSILS AND ADENOIDS 474.9 UNSPECIFIED 475 PERITONSILLAR ABSCESS 476 CHRONIC LARYNGITIS AND LARYNGOTRACHEITIS 476.0 CHRONIC LARYNGITIS 476.1 CHRONIC LARYNGOTRACHEITIS 477 ALLERGIC RHINITIS 477.0 DUE TO POLLEN 477.8 DUE TO OTHER ALLERGEN 477.9 CAUSE UNSPECIFIED 478 OTHER DISEASES OF -

Respiratory Disease in Cork Workers ('Suberosis')1

Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thx.28.4.409 on 1 July 1973. Downloaded from Thorax (1973), 28, 409. Respiratory disease in cork workers ('suberosis')1 J. CORTEZ PIMENTEL and RAMIRO AVILA Department of Pathology of Sanatorio D. Carlos I and Department of Chest Diseases and Institute of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Lisbon, Portugal Pimentel, J. Cortez, and Avila, Ramiro (1973). Thorax, 28, 409-423. Respiratory disease in cork workers ('suberosis'). A clinical, immunological, and histological study of 63 workers in the cork industry with bronchopulmonary manifestations is described. From this study, it was possible to recognize three types of reaction to the inhalation of cork dust: asthma-like syndromes, extrinsic allergic alveolitis, and chronic bronchitis with bronchiec- tasis. The place ofhistological (lung biopsy and scalene node biopsy) and immunological met- hods in the diagnosis of these different forms of the disease is evaluated. The high incidence of precipitins to Penicilliumfrequentans is stressed because the antigens produced by this fungus seem to be more pathogenic than those produced by the mouldy cork itself. The histological studies have demonstrated extrapulmonary foci of disease and have also revealed for the first time, abnormalities in the lungs of symptomless subjects. Pathological changes present in the lungs of patients with the chronic form of extrinsic allergic alveolitis, long after removal from exposure to cork dust, are also described. The experimental material of Horta and Cancella (1956) is reviewed in the light ofpresentknowledge, andthe similarity between the lesions produced in animals and those found in cork workers is noted. Finally, especial im- portance is attached to the finding of cork dust within the lesions, the technique for its identifi- cation and staining being described. -

Occupational Medicine Symposia

OCCUPATIONAL MEDICINE SYMPOSIA U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION, AND WELFARE Public Health Service Center for Disease Control National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Division of Occupational Health Programs ----- - . Rockville,. ·-- --r---�--Maryland May 1975 This publication contains major papers presented at the 34th American Medical Association Congress on Occupational Health, held September 9 to 10, 1974 in Chicago, Illinois. The Congress was supported in part by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health through Contract No. CDC-99-74-30. Dr. Henry Howe was AMA Project Director and compiled the initial proceedings from the verbatim transcript. The assistance of the following individuals is gratefully acknowledged: Ernest B. Howard, M.D. William R. Barclay, M.D. Asher J. Finkel, M.D. Henry F. Howe, M.D. CDC-NIOSH David J. Sencer, M.D. Marcus M. Key, M.D. Raymond T. ~oore, M.D. A. Walter Hoover, M.D. Leo A. Sanders Marilyn K. Hutchison, M.D. HEW Publication No. (NIOSH) 75-189 FOREWORD A primary goal of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health is to promote effective health care for American working men and women. Since the passage of the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970, a growing number of family practitioners and internists have entered the part-time practice of occupational medicine. Helping these physicians to incorporate the concepts and skills of occupational medical practice into the total delivery of health services is a major consideration of the Institute's Division of Occupational Health Programs. Toward this end, NIOSH co-sponsored the AMA's 34th Annual Congress on Occupational Health and cooperated in developing the scientific program for the Congress. -

ICD-9 Diagnosis Codes Effective 10/1/2007 (V25.0) Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

ICD-9 Diagnosis Codes effective 10/1/2007 (v25.0) Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 0010 CHOLERA D/T VIB CHOLERAE 0082 AEROBACTER ENTERITIS 01104 TB LUNG INFILTR-CULT DX 0011 CHOLERA D/T VIB EL TOR 0083 PROTEUS ENTERITIS 01105 TB LUNG INFILTR-HISTO DX 0019 CHOLERA NOS 00841 STAPHYLOCOCC ENTERITIS 01106 TB LUNG INFILTR-OTH TEST 0020 TYPHOID FEVER 00842 PSEUDOMONAS ENTERITIS 01110 TB LUNG NODULAR-UNSPEC 0021 PARATYPHOID FEVER A 00843 INT INFEC CAMPYLOBACTER 01111 TB LUNG NODULAR-NO EXAM 0022 PARATYPHOID FEVER B 00844 INT INF YRSNIA ENTRCLTCA 01112 TB LUNG NODUL-EXAM UNKN 0023 PARATYPHOID FEVER C 00845 INT INF CLSTRDIUM DFCILE 01113 TB LUNG NODULAR-MICRO DX 0029 PARATYPHOID FEVER NOS 00846 INTES INFEC OTH ANEROBES 01114 TB LUNG NODULAR-CULT DX 0030 SALMONELLA ENTERITIS 00847 INT INF OTH GRM NEG BCTR 01115 TB LUNG NODULAR-HISTO DX 0031 SALMONELLA SEPTICEMIA 00849 BACTERIAL ENTERITIS NEC 01116 TB LUNG NODULAR-OTH TEST 00320 LOCAL SALMONELLA INF NOS 0085 BACTERIAL ENTERITIS NOS 01120 TB LUNG W CAVITY-UNSPEC 00321 SALMONELLA MENINGITIS 00861 INTES INFEC ROTAVIRUS 01121 TB LUNG W CAVITY-NO EXAM 00322 SALMONELLA PNEUMONIA 00862 INTES INFEC ADENOVIRUS 01122 TB LUNG CAVITY-EXAM UNKN 00323 SALMONELLA ARTHRITIS 00863 INT INF NORWALK VIRUS 01123 TB LUNG W CAVIT-MICRO DX 00324 SALMONELLA OSTEOMYELITIS 00864 INT INF OTH SML RND VRUS 01124 TB LUNG W CAVITY-CULT DX 00329 LOCAL SALMONELLA INF NEC 00865 INTES INFEC CALCIVIRUS 01125 TB LUNG W CAVIT-HISTO DX 0038 SALMONELLA INFECTION NEC 00866 INTES INFEC ASTROVIRUS 01126 TB LUNG W CAVIT-OTH -

(001-139) Includes: Diseases Generally Recogniz

ICD9 Cause of Death list 1 of 609 CLASSIFICATION OF DISEASES AND INJURIES I. INFECTIOUS AND PARASITIC DISEASES (001-139) Includes: diseases generally recognized as communicable or transmissible as well as a few diseases of unknown but possibly infectious origin Excludes: acute respiratory infections (460-466) influenza (487.-) certain localized infections Note: Categories for "late effects" of infectious and parasitic diseases are to be found at 137.- to 139.- INTESTINAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES (001-009) Excludes: helminthiases (120-129) 001 Cholera 001.0 Due to Vibrio cholerae 001.1 Due to Vibrio cholerae el tor 001.9 Unspecified 002 Typhoid and paratyphoid fevers 002.0 Typhoid fever Typhoid (fever) (infection) [any site] 002.1 Paratyphoid fever A 002.2 Paratyphoid fever B 002.3 Paratyphoid fever C 002.9 Paratyphoid fever, unspecified 003 Other salmonella infections Includes: infection or food poisoning by Salmonella [any serotype] ICD9 Cause of Death list 2 of 609 003.0 Salmonella gastroenteritis Salmonellosis 003.1 Salmonella septicaemia 003.2 Localized salmonella infections Salmonella: Salmonella: arthritis osteomyelitis meningitis pneumonia 003.8 Other 003.9 Unspecified Salmonella infection NOS 004 Shigellosis Includes: bacillary dysentery 004.0 Shigella dysenteriae Infection by group A Shigella (Schmitz) (Shiga) 004.1 Shigella flexneri Infection by group B Shigella 004.2 Shigella boydii Infection by group C Shigella 004.3 Shigella sonnei Infection by group D Shigella 004.8 Other 004.9 Unspecified 005 Other food poisoning (bacterial) Excludes: salmonella infections (003.-) toxic effect of noxious foodstuffs (988.-) ICD9 Cause of Death list 3 of 609 005.0 Staphylococcal food poisoning Staphylococcal toxaemia specified as due to food 005.1 Botulism Food poisoning due to Clostridium botulinum 005.2 Food poisoning due to Clostridium perfringens [Cl. -

Wildfires in Northern California: Emergency Department Visits, 2017

Wildfires in Northern California: Emergency Department Visits in 2017 We wish to acknowledge the HCUP Partner organization from the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD) that contributed to the HCUP State Databases used in this study. May 29, 2019 Recommended Citation: Wildfires in Northern California: Emergency Department Visits in 2017. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. ONLINE. August 19, 2019. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports.jsp. Table of Contents Overview ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 Air Quality Index ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Methods ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 Groupings of California Counties .............................................................................................................. 2 Air Quality Data ......................................................................................................................................... 4 HCUP Databases ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Conditions of Interest .............................................................................................................................. -

Particles Causing Lung Disease by Kaye H

Environmental Health Perspectives Vol. 55, pp. 97-109, 1984 Particles Causing Lung Disease by Kaye H. Kilburn* The lung has a limited number of patterns of reaction to inhaled particles. The disease observed depends upon the location: conducting airways, terminal bronchioles and alveoli, and upon the nature of inflammation induced: acute, subacute or chronic. Many different agents cause narrowing of conducting airways (asthma) and some of these cause permanent distortion or obliteration of airways as well. Terminal bronchioles appear to be particularly susceptible to particles which cause goblet cell metaplasia, mucous plugging and ultimately peribronchiolar fibrosis. Cancer is the last outcome at the bronchial level and appears to depend upon continuous exposure to or retention of an agent in the airway and failure of the affected cells to be exfoliated which may be due to squamous metaplasia. Alveoli are populated by endothelial cells, lype I or pavement epithelial cells and metabolically active cuboidal Type II cells that produce the lungs specific surfactant, dipalmytol lecithin. Disturbances of surfactant lead to edema in distal lung while laryngeal edema due to anaphylaxis or fumes may produce asphyxia. Physical retention of indigestible particles or retention by immune memory responses may provoke hyaline membranes, stimulate alveolar lipoproteinosis and finally fibrosis. This later exuberant deposition of connective tissue has been best studied in the occupational pneumoconioses especially silicosis and asbestosis. In contrast emphysema a catabolic response, appears frequently to result from leakage or release of lysosomal proteases into the lung during processing of cigarette smoke particles. The insidious and probably most important human lung disease due to particles is bronchiolar obstruction and obliteration, producing progressive impairment of air flow.