Policy Proposal: an Anti-Racist West Point

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Racism and Bad Faith

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Gregory Alan Jones for the degree ofMaster ofArts in Interdisciplinary Studies in Philosophy, Philosophy and History presented on May 5, 2000. Title: Racism and Bad Faith. Redacted for privacy Abstract approved: Leilani A. Roberts Human beings are condemned to freedom, according to Jean-Paul Sartre's Being and Nothingness. Every individual creates his or her own identity according to choice. Because we choose ourselves, each individual is also completely responsible for his or her actions. This responsibility causes anguish that leads human beings to avoid their freedom in bad faith. Bad faith is an attempt to deceive ourselves that we are less free than we really are. The primary condition of the racist is bad faith. In both awarelblatant and aware/covert racism, the racist in bad faith convinces himself that white people are, according to nature, superior to black people. The racist believes that stereotypes ofblack inferiority are facts. This is the justification for the oppression ofblack people. In a racist society, the bad faith belief ofwhite superiority is institutionalized as a societal norm. Sartre is wrong to believe that all human beings possess absolute freedom to choose. The racist who denies that black people face limited freedom is blaming the victim, and victim blaming is the worst form ofracist bad faith. Taking responsibility for our actions and leading an authentic life is an alternative to the bad faith ofracism. Racism and Bad Faith by Gregory Alan Jones A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies Presented May 5, 2000 Commencement June 2000 Redacted for privacy Redacted for privacy Redacted for privacy Redacted for privacy Redacted for privacy Redacted for privacy Acknowledgment This thesis has been a long time in coming and could not have been completed without the help ofmany wonderful people. -

Drill Sergeants Guide Cadet Cadre Through CST by Eric S

AUGUST 20, 2020 1 WWW.WESTPOINT.EDU THE AUGUST 20, 2020 VOL. 77, NO. 32 OINTER IEW® DUTY, HONOR, COUNTRY PSERVING THE U.S. MILITARY ACADEMY AND THE COMMUNITY V OF WEST POINT ® SEE PAGES 4-6 • • BACK TO CLASS AT WEST POINT The U.S. Military Academy holds its fi rst day of classes Monday. Classes were taught in person, remotely and through a hybrid system. It marked the fi rst time cadets attended classes in person since they left for spring break in March. (Top) Maj. John Morrow teaches General Psychology for Leaders while taking advantage of one of the temporary outdoor classrooms. (Above) Members of the Corps of Cadets change classes during the fi rst day of the academic year. (Left) Class of 2022 Cadet Xavier Williams attends a remote class. Photos by Brandon O'Connor/PV and Class of 2022 Cadet Paul Tan 2 AUGUST 20, 2020 NEWS & FEATURES POINTER VIEW West Point conducts a ribbon-cutting ceremony to recognize the reopening of Grant Hall at West Point Friday. The offi cial party consists of (left to right) Joe Kokolakis, president, J. Kokolakis Construction; Maria Hoagland, GM Culinary Group, U.S. Military Academy; Brig. Gen. Curtis A. Buzzard, Commandant of Cadets; Col. Tom Hansbarger, director of Cadet Activities; Maj. Matthew Pride, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, New York District Offi ce; and Frank Bloomer, deputy director, DPW, USMA. Photo by John Pellino/USMA PAO Grant Barracks, Hall reopen after renovation By Dave Conrad a media release from the ACOE. Cain said that the new air conditioning reopened Saturday, but a ribbon cutting USAG West Point Public Affairs “After the renovation, the barracks will system is probably the biggest quality-of- ceremony was held the day before bringing have a more traditional layout,” Tim Cain, life improvement, but it wasn’t the biggest together the many agencies that worked on One of West Point’s oldest barracks the project engineer, said. -

Title: a CRITICAL EXAMINATION of ANTI-INDIAN RACISM in POST

Title: A CRITICAL EXAMINATION OF ANTI-INDIAN RACISM IN POST-APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA Student Name: ANNSILLA NYAR Student No: 441715 Supervisor: DR STEPHEN LOUW Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of the Witwatersrand (Wits). Department of Political Studies Faculty of Humanities University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) 15 March 2016 1 DECLARATION The candidate hereby confirms that the dissertation submitted is her own unaided work and that appropriate credit has been accorded where reference has been made to the work of others. Signed: Annsilla Nyar Student # 441715 2 A Critical Examination of Anti-Indian Racism in Post-Apartheid South Africa Abstract: This dissertation is a critical examination of anti-Indian racism in post-apartheid South Africa. While racism presents an intractable problem for all racial groups in South Africa, this dissertation will show that Indian South Africans are especially framed by a specific racist discourse related to broad perceptions of economic exploitation within the context of redistributive and resource-allocation conflicts, political corruption, insularity and general lack of a socio-cultural ‘fit’ with the rest of South African society. This is not unique to present day South Africa and is (albeit in evolving ways) a long standing phenomenon. Key concerns addressed by the dissertation are: the lack of critical attention to the matter of anti-Indian racism, the historical origins of anti-Indian racism, the characteristics and dynamics of anti-Indian racism and its persistence in post-apartheid South Africa despite an avowed commitment of South Africa’s new post-apartheid dispensation to a non-racial society. -

DMAVA Highlights Jan

DMAVA Highlights Jan. 21, 2010 Volume 12 Number 02 108th Wing Engineers leave for deployment to Iraq Airmen of the 108th Civil Engineer Squadron say farewell to family members. More than 60 members of the 108th Civil Engineer Squadron, Coffee Express keeps ‘em going New Jersey Air National Guard, left New Jersey Dec. 27-28 for a six- month deployment to Iraq. The “Coffee Express” provides deployed Airmen and Soldiers On Jan. 8 the main body of the squadron arrived at their duty loca- with coffee and snack food. You can send packages of snacks and tion in Iraq. Lt. Col. Paul Novello, in a formal change of command cer- coffee to keep the members of the 108th Civil Engineer Squadron emony, assumed command of the 447th Expeditionary Civil Engineer- remembering home. If interested, drop an e-mail to Barbara.harbi- ing Squadron at the forward operating location. Photos by Maj. Yvonne Mays, DMAVA Public Affairs Office. [email protected] or call 609-530-7088 for the addresses. Governors official photos are ready Post extends invitation to Jewish war veterans The official photos of Gov. Chris Chris- tie are ready for the armories. Please An invitation is extended to any Soldier or Airman of the Jew- ish faith to join the Specialist Marc Seiden Post 444 of the Jewish send an e-mail to Barbara.harbison@ War Veterans. The veterans meet on the third Thursday of the njdmava.state.nj.us with the unit, address month at the Twin Rivers library located in East Windsor, N.J. Spc. -

Cadet Gray : a Pictorial History of Life at West Point As Seen Through Its

C'.jMs * V. *$'.,. yft v5sp»hV -• sp:km■&■:: -. SlKfHWt:'Yr'^ if*## w ■W.» H'• mATAA imflmt,mWw- mm ■M fwi uwJuSuU;rt”i> i ifyffiiRt >11 OT»X; w^lssii' ^;fL--„i‘. • ■•'■&»> .‘ 44 V . ir'YVV. <iVv -\\#■ • - . < •? ■ .« *5 ^'*V • *’vJ* •"•''' i\ ' p,'ii*.^55?V'..'S *'•• • ■ ’■4v YU'r '• iii#>«;•.' >v . •" S/M .'.fi'i -ft' ,' 1« ■ wafts. | if ~*^kl \ l\ % . • — CADET * . CRAY ■ A cadet officer (with chevrons) and a Plebe in "50-50” Full Dress, on the Plain at West Point. The officer’s insignia denote that he is a Distinguished Cadet, a lieu¬ tenant, and a First Classman. msm \ PICTORIAL HISTORY OF LIFE AT WEST POINT AS SEEN THROUGH ITS UNIFORMS !Y FREDERICK P. TODD, COL,, U.S.A.R. ILLUSTRATED BY FREDERICK T. CHAPMAN I i ■ ••••:1 ^ ■—1 To My Wife By the Same Author SOLDIERS OF THE AMERICAN ARMY Copyright, 1955 by STERLING PUBLISHING CO., Inc. 215 East 37 St., New York 16, N. Y. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 55-12306 This edition is published by Bonanza Books, a division of Crown Publishers, Inc. by arrangement with the original publisher, Sterling Co., Inc. Contents The United States Military Academy . What Cadet Gray Means. 11 The First Uniform . 15 Republican Styles . 19 Partridge’s Gray Uniform. 22 Cadet Dress in Thayer’s Time . 25 The West Point Band . 32 Plumes, Swords and Other Distinctions. 38 Fatigue and Foul Weather Clothing. 44 In the 1850’s and ’60’s. -

A Taste of New England

Join the Southington Adult Education United States Military Academy At West Point May 2, 2015 The United States Military Academy at West Point is proud of its reputation as a leading Developer of military recruits, educating, training and inspiring each cadet in the value Of duty, honor and country. The Corps of Cadets, West Point’s student body, numbers 4400. Each year, approximately 1000 cadets graduate to undertake commissions as Second lieutenants in the US Army. Tour Highlights RT motorcoach transportation West Point Tour Informative and exciting, there is no better way to experience the sweep of America’s history Than with a tour of West Point. View breathtaking scenery from West Point which Overlooks the Hudson River as it winds through the Hudson Highlands. Historic figures such as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Douglas MacArthur, Dwight Eisenhower and even Benedict Arnold all have a role in the story of West Point and our nation. This tour will make stops at the Main Cadet Chapel, Trophy Point, Battle Monument And the Plain. Lunch at the Thayer Hotel A Legendary Setting with Spectacular River Views! Seated on a hilltop in Upstate New York, with commanding views of the Hudson River and The United States Military Academy at West Point, the Historic Thayer Hotel is a national Historic treasure visited by past US Presidents, international leaders and celebrities. West Point Parade Review The Review is a highlight of the visitors experience at West Point. It starts with the West Point Rifle Drill Team followed by the Brigade Review—including the West Point Band. -

1 West Point Brigade Boxing Open, 6 P.M. Friday at Crest Hall

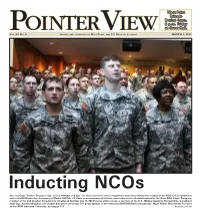

WestMarch 1,Point 2012 1 Brigade Boxing Open, 6 p.m. Friday at Crest Hall. OINTER IEW® PVOL. 69, NO. 9 SERVING THE COMMUNITY OF WEST POINT V, THE U.S. MILITARY ACADEMY MARCH 1, 2012 Inducting NCOs Sgt. 1st Class Trenton Zaragoza, Sgt. James Aldridge and Sgt. 1st Class Jennifer Lennox stood front and center during the reciting of the NCO Creed toward the end of the NCO Induction Ceremony at Mahan Hall Feb. 23. Forty noncommissioned officers were inducted into the brotherhood of the Army NCO Corps. Zaragoza, member of the 2nd Aviation Detachment, introduced Aldridge into the NCO Corps while Lennox, a member of the U.S. Military Academy Dental Clinic, introduced Staff Sgt. Josefino Majadas (not shown) during the ceremony. The guest speaker at the event was NORTHCOM Command Sgt. Major Robert Winzenried. For more on the NCO Induction Ceremony, see pages 8-9. KATHY EASTWOOD/PV 2 March 1, 2012 Commentary Pointer View Spring break safety—for a safe return Reprinted from safespringbreak.org and reapply often. Pay extra attention to ears, nose, face and shoulders. Spring break is a time for college students to let loose of all Fair skinned individuals should wear sunglasses and even the stresses and frustrations built up during the academic year. a hat. Avoid sun exposure during the hottest hours of the sun’s However, it is important to be cautious of not going to an rays and remember you can burn even when it’s cloudy. extreme during a time of frivolity. • Swimming—jumping into the water without a lifeguard Here are some steps to take to make sure you have a safe is risky. -

First Year Students' Narratives of 'Race' and Racism in Post-Apartheid South

University of the Witwatersrand SCHOOL OF HUMAN AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT Department of Psychology First year students’ narratives of ‘race’ and racism in post-apartheid South Africa A research project submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for Masters in Educational Psychology in the Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, November 2011 Student: Kirstan Puttick, 0611655V Supervisor: Prof. Garth Stevens DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own unaided work. It is submitted for the Degree of Master in Educational Psychology at the University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any other degree or examination at any other university. Kirstan Puttick November 2011 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are several people whom I would like to acknowledge for their assistance and support throughout the life of this research project: Firstly, I would like to extend my sincere thanks to my supervisor, Prof. Garth Stevens, for his guidance, patience and support throughout. Secondly, I would like to thank the members of the Apartheid Archive Study at the University of the Witwatersrand for all their direction and encouragement. Thirdly, I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to all my friends and family who have been a tremendous source of support throughout this endeavour. I would also like to thank my patient and caring partner for all his kindness and understanding. Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, I would like to thank my participants without whom this project would not have been possible. I cannot begin to express how grateful I am for the contributions that were made so willingly and graciously. -

Cadets Trace Military History in Germany

APRIL 3, 2014 1 THE APRIL 3, 2014 VOL. 71, NO. 13 OINTER IEW® DUTY, HONOR, COUNTRY PSERVING THE U.S. MILITARY ACADEMY AND THE COMMUNITY V OF WEST POINT The ® Art of WarSee Pages 10-11 MIKE STRASSER/PV Gen. Martin Women’s Team INSIDE Dempsey returns Handball hosts to alma mater; memorial & talks with ‘14. tournament. ONLINE WWW . POINTERVIEW . COM JOHN PELLINO/DPTMS/VI MIKE STRASSER/PV WWW . USMA . EDU SEE PAGE 3 SEE PAGE 6 2 APRIL 3, 2014 NEWS & FEATURES POINTER VIEW Team excels at Bataan Memorial The “Long Gray Line” team of West Point cadets came in first place at the 25th annual Bataan Memorial Death March at White Sands Missile Range, N.M., March 23. (From left) Class of 2017 Cadet Austin Willard, Class of 2015 Cadet Kevin Whitham, Class of 2014 Cadet Louis Tobergte, Class of 2015 Cadet Kyle Warren and Class of 2015 Cadet Ben Ficke competed in the Military Male Heavy Team category and finished the 26.2-mile march in 5 hours, 26 minutes. (Far left) Class of 2014 Cadet Jessica Niemiec placed fourth in the Military Female Individual Heavy division with a time of 6 hours, 30 minutes. Marchers in the heavy divisions all had a minimum of 35 pounds in their rucksacks/backpacks, which were weighed and verified at the finish line. PHOTO BY STAFF SGT. VITO BRYANT/USMA PAO Deadline looms for taxpayers By the West Point Tax Center • W-2’s for all salary income earned; • 1099-INT for all interest received on The West Point Tax Center continues to see investments and bank accounts; clients on an appointment basis Monday, Tuesday, • 1099-DIV for dividends received on stocks; Thursday and Friday from 9 a.m.-noon and 2-5 p.m. -

Avodah Racial Justice Guide

Avodah Racial Justice Guide Historically, Jews of Color have been systematically marginalized, discredited, and discounted within Jewish organizations. Still today, our Jewish institutions rarely reflect the true diversity within the Jewish community. The Jewish community is stronger and more authentically rooted in justice when everyone has an equal seat at the table. This moment calls us to do the best, most authentic, and most effective work for justice that we can. We know that there are many kinds of injustice in our world, including racism, antisemitism, and white supremacy. This guide approaches our drive towards diversity, equity, and inclusion, primarily through a lens of race; it offers ways to understand, and work against, racism in our organizations. However, we also acknowledge the ways in which racism is intertwined with other forms of oppression, and in particular how antisemitism and racism are linked through white supremacy in the United States. To do our part in dismantling these systems of oppression and building a better, more just world, we need to understand how they affect each other, and we must do true coalition building. This is a pivotal time in the Jewish community as the COVID-19 pandemic and a widespread grappling with systemic racism have changed what it means to be in community and underlined the need for deep and meaningful change. The economic implications of the pandemic have yet to be fully realized, but as organizations look to tighten their budgets, racial equity and inclusion must not only remain a line item but also a foundation for building Jewish continuity. -

Rising Yearlings Ramping up CFT Training

JULY 18, 2019 1 THE JULY 18, 2019 VOL. 76, NO. 27 ® UTY ONOR OUNTRY OINTER IEW D , H , C PSERVING THE U.S. MILITARY ACADEMY AND THE COMMUNITY V OF WEST POINT ® POINTER VIEW INSIDE & ONLINE WWW . USMA . EDU Zeroing in WWW . POINTERVIEW . COM New Commandant takes command of Corps of Cadets on Target A Class of 2022 cadet in 5th Company goes through Introduction SEE PAGE 7 to Patrolling prior to his fi eld training exercise during Cadet Field Training July 12. See Page 3 for more Cadet Field Training photos from summer training. Photo by Brandon O’Connor/PV 2 JULY 18, 2019 NEWS & FEATURES POINTER VIEW USMA hosts members of Congress on future needs By Brandon O’Connor Assistant Editor The U.S. Military Academy hosted six members of the House of Representatives for a tour July 7-9 to talk about the future needs of the academy as it works to develop future leaders for the Army. The congressional representatives were invited by Rep. Steve Womack, the chair of the Board of Visitors, to tour West Point’s training facilities and learn more about how the academy is working to prepare Soldiers to lead in future combat. “I think the least we should be able to do is ensure that the training environment they have and the resources they have with which to train our future Army leaders, young men and women from our own respective districts, are the very best we can provide,” Womack said. “I think just one quick glance around Camp Buckner, it doesn’t take you very long to figure out we can do better than this.” During their visit, the delegates had the chance to tour the training areas at Camp USMA Superintendent Lt. -

Building a Multi-Ethnic, Inclusive & Antiracist Organization

Building a Multi-Ethnic, Inclusive & Antiracist Organization Tools for Liberation Packet for Anti-Racist Activists, Allies, & Critical Thinkers For more information about our Anti-Racism Institute or to schedule an anti-racism training or consultation for your organization, please contact Nancy Chavez-Porter, Training and Community Education Director: 303-449-8623 [email protected] www.safehousealliance.org Tools for Liberation Packet Contents 1. Anti-Racism Definitions From A Human Rights Framework 3-4 2. Acts/Omissions – Overt/Covert Racism 5 3. Characteristics of Dominants and Subordinates 6 4. The Intersectionality of Oppression 7 5. The Usual Statements 8 6. A Chronicle of the Problem Woman of Color in Non-Profits 9 7. The Organizational Spiral 10 8. Characteristics of a Highly Inclusive Organization 11-12 9. Qualities of a Committed CEO 13 10. Qualities of an Anti-Racist Ally 14 These “Tools for Liberation” reflect years of hard work by staff who engage in anti- racist organizing on a daily basis, and are the intellectual property of the Safehouse Progressive Alliance for Nonviolence (SPAN). Do not reprint without permission. Please contact us for information about reusing this material. Core Reading List • Color of Violence: The Incite! Anthology . South End Press, 2006. • Race, Class, and Gender in the United States . Paula S.Rothenberg (ed). 6 th Edition.Worth, 2004 • Living Chicana Theory . Carla Trujillo (ed). Third Woman Press,1998. • Sister Outsider . Audre Lorde. The Crossing Press, 1984. • Women, Race and Class . Angela Y. Davis. Vintage Books, 1983. • Are Prisons Obsolete ? Angela Y. Davis. Seven Stories Press, 2003. • The Heart of Whiteness: Confronting Race, Racism and White Privilege .