147 EIGHTH AVENUE HOUSE, Manhattan Built C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brooklyn Transit Primary Source Packet

BROOKLYN TRANSIT PRIMARY SOURCE PACKET Student Name 1 2 INTRODUCTORY READING "New York City Transit - History and Chronology." Mta.info. Metropolitan Transit Authority. Web. 28 Dec. 2015. Adaptation In the early stages of the development of public transportation systems in New York City, all operations were run by private companies. Abraham Brower established New York City's first public transportation route in 1827, a 12-seat stagecoach that ran along Broadway in Manhattan from the Battery to Bleecker Street. By 1831, Brower had added the omnibus to his fleet. The next year, John Mason organized the New York and Harlem Railroad, a street railway that used horse-drawn cars with metal wheels and ran on a metal track. By 1855, 593 omnibuses traveled on 27 Manhattan routes and horse-drawn cars ran on street railways on Third, Fourth, Sixth, and Eighth Avenues. Toward the end of the 19th century, electricity allowed for the development of electric trolley cars, which soon replaced horses. Trolley bus lines, also called trackless trolley coaches, used overhead lines for power. Staten Island was the first borough outside Manhattan to receive these electric trolley cars in the 1920s, and then finally Brooklyn joined the fun in 1930. By 1960, however, motor buses completely replaced New York City public transit trolley cars and trolley buses. The city's first regular elevated railway (el) service began on February 14, 1870. The El ran along Greenwich Street and Ninth Avenue in Manhattan. Elevated train service dominated rapid transit for the next few decades. On September 24, 1883, a Brooklyn Bridge cable-powered railway opened between Park Row in Manhattan and Sands Street in Brooklyn, carrying passengers over the bridge and back. -

Cultural Guide for Seniors: Brooklyn PHOTOGRAPHY

ART / DESIGN ARCHITECTURE DANCE / SING THEATRE / LIVE MONUMENTS GALLERIES / ® PARKSCultural Guide for Seniors: Brooklyn PHOTOGRAPHY Acknowledgments NYC-ARTS in primetime is made possible in part by First Republic Bank and by the Rubin Museum of Art. Funding for NYC-ARTS is also made possible by Rosalind P. Walter, The Paul and Irma Milstein Foundation, The Philip & Janice Levin Foundation, Elise Jaffe and Jeffrey Brown, Jody and John Arnhold, and The Lemberg Foundation. This program is NYC-ARTS.org supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council. On multiple platforms, Thirteen/WNET’s Additional funding provided by members of NYC-ARTS aims to increase awareness of THIRTEEN. New York City’s nonprofit cultural organizations, whose offerings greatly benefit We are grateful to Megan Flood for residents and visitors—from children to adults, contributing the design of the cover of this and teenagers to senior citizens. publication. NYC-ARTS promotes cultural groups’ We are grateful for the cooperation of the activities and events to tri-state, national and cultural organizations that supplied information international audiences through nonprint media, for this guide. using new technologies as they develop. Through websites, television, mobile applications and social media, NYC-ARTS This program is supported, in part, by nurtures New York City’s position as a public funds from the New York City thriving cultural capital of the world, one that Department of Cultural Affairs. has both world renowned institutions and those that are focused on local communities. WNET 825 Eighth Avenue New York, NY 10019 http://WNET.org (212) 560-2000 Cover Design: Megan Flood Copyright © 2012 WNET Table of Contents A.I.R./Artists in Residence Gallery............................................................................. -

NYCHA Facilities and Service Centers

NYCHA Facilities and Service Centers BOROUGH DEVELOPMENT NAME ADDRESS Manhattan Baruch 595- 605 FDR Drive Staten Island Berry Houses 44 Dongan Hills Brooklyn Farragut 228 York Street Manhattan Harborview Terrace 536 West 56th Street Brooklyn Howard 1620 E N Y Avenue Manhattan Lexington 115 East 98th Steet Brooklyn Marcus Garvey 1440 E N Y Avenue Bronx Monroe 1802 Story Avenue Bronx Pelham Parkway 975 Waring Avenue Brooklyn Pink 2702 Linden Boulevard Queens Ravenswood 34-35A 12th Street Queens Ravenswood 34-35A 12th Street Brooklyn Red Hook East 110 West 9th Street Brooklyn Saratoga Square 930 Halsey Street Manhattan Washington Hts Rehab (Groups I and II) 500 West 164th Street Manhattan Washington Hts Rehab (Groups I and II) 503 West 177th Street Manhattan Wilson 405 East 105th Steet Manhattan Wise Towers/WSURA 136 West 91st Steet Brooklyn Wyckoff Gardens 266 Wyckoff Street Page 1 of 148 10/01/2021 NYCHA Facilities and Service Centers POSTCO STATUS SPONSOR DE Occupied Henry Street Settlement, Inc. Occupied Staten Island Mental Health Society, Inc. 10306 Occupied Spanish Speaking Elderly Council - RAICES Occupied NYCHA 10019 NYCHA HOLD NYCHA 11212 Occupied Lexington Children's Center 10029 Occupied Fort Greene Senior Citizens Council 11212 Vacant NYCHA Occupied Jewish Association Services For the Aged Occupied United Community Centers Occupied HANAC, Inc. 11106 Occupied HANAC, Inc. Occupied Spanish Speaking Elderly Council - RAICES Occupied Ridgewood-Bushwick Sr Citizens Council, Inc. Vacant NYCHA Occupied Provider Name Unknown Occupied -

Shot to Death at the Loft

SATURDAY • JUNE 12, 2004 Including The Bensonhurst Paper Brooklyn’s REAL newspapers Published every Saturday — online all the time — by Brooklyn Paper Publications Inc, 55 Washington St, Suite 624, Brooklyn NY 11201. Phone 718-834-9350 • www.BrooklynPapers.com • © 2004 Brooklyn Paper Publications • 16 pages • Vol. 27, No. 24 BRZ • Saturday, June 19, 2004 • FREE Shot to death at The Loft By Jotham Sederstrom Police say the June 12 shooting happened in a basement bathroom The Brooklyn Papers about an hour before the bar was to close. Around 3 am, an unidentified man pumped at least four shots into A man was shot to death early Saturday morning in the bath- Valdes, who served five years in prison after an arrest for robbery in room of the Loft nightclub on Third Avenue in Bay Ridge. 1989, according to Kings County court records. The gunman, who has Mango / Greg Residents within earshot of the club at 91st Street expressed concern thus far eluded police, may have slipped out the front door after climb- but not surprise at the 3 am murder of Luis Valdes, a Sunset Park ex- ing the stairs from the basement, say police. convict. Following the murder, Councilman Vincent Gentile voiced renewed “That stinkin’ place on the corner,” said Ray Rodland, who has lived support for legislation that would allow off-duty police officers to moon- on 91st Street between Second and Third avenues for 20 years. “Even light as bouncers — in uniform — at bars and restaurants. The bill is Papers The Brooklyn if you’re farther away, at 4 in the morning that boom-boom music currently stalled in a City Council subcommittee for public housing. -

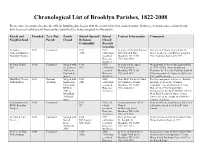

Chronological List of Brooklyn Parishes and Schools- 2012

Chronological List of Brooklyn Parishes, 1822-2008 Please note: in canonical terms, the official founding date begins with the arrival of its first resident pastor. However, in many cases, a church may have been served by priests from another parish before being assigned its own pastor. Parish and Founded Terr./Nat. Parish School Opened/ School Contact Information Comments Neighborhood Parish Closed Religious Closed/ Community Records Location St. James 1822 Territorial 1823 1973 St. James Cathedral-Basilica Site of first Catholic high school, St. Cathedral-Basilica, (CSJ) (All school 250 Cathedral Place James Academy (now Bishop Loughlin Brooklyn Heights records at Brooklyn, NY 11201 H.S.) Named a Basilica in 1982. Diocesan (718) 852-4002 Archives) St. Paul, Cobble 1838 Territorial Merged with 1838 1975 St. Paul and St. Agnes Merged with St. Peter-Our Lady of Pilar Hill St. Agnes in (SC) (All school 234 Congress St. in 1975. Oldest church building in 2007 as St. records at Brooklyn, NY 11201 Brooklyn. St. Peter/St. Paul/Our Lady of Paul and St. Diocesan (718) 624-3425 Pilar merge with St. Agnes in 2007 as St. Agnes Archives) Peter and St. Agnes. Most Holy Trinity, 1841 National Merged with 1841 2005 Most Holy Trinity-St. Mary First German parish in Diocese. Known Williamsburg (German) Immaculate (OP) (All school 138 Montrose Avenue for many years as the “German Conception records at Brooklyn, NY 11201 Cathedral.” Site of Most Holy Trinity BVM in Diocesan (718) 384-0215 H.S. (1916-1972) Merged with 2007 as Archives) Immaculate Conception BVM in 2007 as Most Holy Most Holy Trinity-St. -

143 ALLEN STREET HOUSE, 143 Allen Street, Manhattan Built C

Landmarks Preservation Commission February 9, 2010, Designation List 426 LP-2350 143 ALLEN STREET HOUSE, 143 Allen Street, Manhattan Built c. 1830-31 Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 415, Lot 23. On June 23, 2009, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation of the 143 Allen Street House and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 6). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of the law. Four people spoke in favor of designation, including a shareholder in the property and representatives of the Historic Districts Council and the Society for the Architecture of the City. Summary The Federal style row house at 143 Allen Street was constructed c. 1830-31 as a speculative investment by George Sutton, a ship captain and counting house merchant. Originally part of a group of six similar residences, it is located in the heart of what is now known as Manhattan’s Lower East Side on land that was once part of the vast country estate of James De Lancey. The area developed rapidly following the turn of the 19th century and by the 1830s had become a bustling neighborhood composed in large part of brick and brick- fronted Federal style row houses. George Sutton had established himself in the early 19th century as a captain sailing the coastal trade route between New York City and Charleston, South Carolina. He eventually became ship master in the New- York and Charleston Packet Line, and later an agent and merchant working in a counting house on the East River waterfront. -

This Brooklyn Neighborhood Is Cool — and Still Affordable by Adam Bonislawski September 26, 2018 | 7:14Pm | Updated

In search of a larger apartment with character at an affordable price, Christina Poletto and son Theodore recently moved to Sunset Park. Annie Wermiel REAL ESTATE This Brooklyn neighborhood is cool — and still affordable By Adam Bonislawski September 26, 2018 | 7:14pm | Updated Nikki Grossman had her eye on Sunset Park for some time. Formerly a resident of the Lower East Side, Grossman moved to area rental building The Hamilton in June. She says she was drawn to the 98-unit development, which opened two years ago at 968 60th St., by its amenities (which include a fitness center, landscaped roof deck and screening room) and reasonable rents (studios from $2,200, one-bedrooms from $2,350). Though less hyped than other, more celebrated Brooklyn nabes, Sunset Park’s affordable prices and low-key vibe have been luring residents from other city spots and even other counties in the state. Take Christina Poletto, 42, and her 5-year-old son Theodore, who recently relocated to the neighborhood from Rockland County. For Grossman, who grew up in nearby Gravesend, it was also a repatriation of sorts. “I had been living in Manhattan just for proximity to work, but I had been wanting to come home,” says Grossman, 40, a nurse at New York University’s main hospital. “When I learned about [The Hamilton] and all its amenities, I was very interested.” Nikki Grossman moved into The Hamilton, one of the few Sunset Park buildings to boast amenities like a gym and a screening room. Annie Wermiel Little wonder — despite a wave of commercial development and a steadily rising profile, newly built, amenity-rich apartment buildings are still a rarity in Sunset Park. -

A Chronology of 125Th Street

125th Street Chronology • 16th Century Native Americans inhabit summer village at what is now East 125th Street and the Harlem River. • 1609 Henry Hudson trades with Native Americans off the Manhattanville shoreline. • 1658 Pieter Stuyvesant founds the village of Nieuw Haarlem, part of which occupies the land at what would later become East 125th Street between First and Second avenues. • 1776 George Washington defeats the British in the Battle of Harlem Heights, driving the enemy south across what was then called the Hollow Way, later known ofOicially as West 125th Street. • 1806 Village of Manhattanville founded at an inlet along the Hudson River at what will soon become West 125th Street. 1811 The Randel Plan proposes a grid of streets blanketing Manhattan, including an East-West thoroughfare along a geological fault line thereafter known as 125th Street. • 1813 125th Street opens as one of Manhattan’s 15 major cross-town streets • 1814 Regular ferry service begins along the Harlem River from East 125th Street to downtown. • 1850s The public school at East 125th Street and Second Avenue admits it Oirst African-American student. • 1863-1872 Artist Thomas Nast plots the downfall of the Tweed Ring from his backyard studio at Fifth Avenue and 125th Street. • 1869 A group of German Jews relocates from the Lower East Side to East 125th Street and Third Avenue, establishing the core of uptown’s Jewish community. • 1889 Oscar Hammerstein opens the Harlem Opera House at 211 West 125th Street, paving the way for 125th Street’s development as an entertainment district. • 1904 The Interborough Rapid Transit’s Broadway line opens in Upper Manhattan, spanning West 125th Street with a viaduct featuring a 168.5-foot parabolic arch. -

BUNKER MENTALITY CB2 Tells Bloomie to Take Hike

INSIDE BROOKLYN’S WEEKLY NEWSPAPER Including The Downtown News, Carroll Gardens-Cobble Hill Paper and Fort Greene-Clinton Hill Paper ‘Nut’ gala raises $700G for BAM Published weekly by Brooklyn Paper Publications Inc, 26 Court St., Brooklyn 11242 Phone 718-834-9350 AD fax 718-834-1713 • NEWS fax 718-834-9278 © 2002 Brooklyn Paper Publications • 12 pages including GO BROOKLYN • Vol. 25, No. 51 BWN, DTG, PSG, MID • December 30, 2002 • FREE NEW YEAR’S BLAST! BUNKER MENTALITY CB2 tells Bloomie to take hike By Patrick Gallahue The Brooklyn Papers Calling it a hazard to Downtown Brooklyn and its residents, Community Board 2 and Councilman David Yassky this week came down strongly against the city’s plan to build a new Office of Emergency Management headquarters at 165 Cadman Plaza East, the former home of the American Red Cross. / File photo “On public safety grounds I just do not think this is a viable place for such a sensitive facility as the OEM headquarters next to ex- Plans to put the city’s Office of Emergency Management headquar- tremely sensitive, and quite possi- ters at the Red Cross building site at 165 Cadman Plaza East, have The Brooklyn Papers The Brooklyn bly, target facilities, namely the come under fire. The Brooklyn Papers / File photos Brooklyn Bridge and the federal courthouse,” Yassky said. OEM headquarters is built there. ceived a cold response from the Besides stating his position at a The OEM proposal is making its community and he pledged to re- GAP fireworks to mark 2003 public hearing before Borough way through the city’s public re- vise the design. -

Explore Chinatown New York City

1005_China_Brc_Mech_2.qxd 6/30/04 5:32 PM Page 1 Explore the Streets of Chinatown Explore the History of Chinatown 1 MOTT STREET & CANAL STREET 6 CHATHAM SQUARE 11 MAHAYANA BUDDHIST TEMPLE 2 GRAND STREET & MOTT STREET 7 COLUMBUS PARK 12 FIRST SHEARITH ISRAEL CEMETERY 3 DOYERS STREET 8 FIVE POINTS 13 EDWARD MOONEY HOUSE 4 BAXTER STREET 9 MUSEUM OF CHINESE IN THE AMERICAS ••• SUBWAY STATIONS 5 EAST BROADWAY 10 CHURCH OF THE TRANSFIGURATION P PARKING LOTS/GARAGES EXPLORE CHINATOWN NEW YORK CITY 6 Downtown Only F V E HOUSTON ST B D F V LOWER EAST SIDE / 2ND AVENUE STATION W HOUSTON ST BROADWAY / LAFAYETTE ST STATION N ST H ST ST H STANTO BY ST ET AYETTE ST N R W CROS ELIZAB MOTT ST ST MOTT LAF ST MULBERRY PRINCE ST PRINCE ST STATION PRINCE ST RIVINGTON ST AY K ST K Y ST OLK ST OLK ROOSEVELT F R RD ST RD ADW ST X OW A PARK SUFFOL F NO CH ESSE R BRO LUDL 6 BOWER O SPRING ST DELANCEY ST / SPRING ST SPRING ST STATION ESSEX ST STATION J M Z J M Z ST DELANCEY AY ON ST BOWERY STATION DW A IVAN ST O STER ST KENMARE ST R BY ST B P SULL P THOMPS W WOO E AMERICAS E GREENE ST MERCER ST CROS BROOME ST BROOME ST BROOME ST OF TH OF P B D ENUE ENUE P P GRAND ST STATION P AV GRAND ST P GRAND ST 2 1 9 A C E SEWARD PARK P CANAL ST STATION ST ST P HOWARD ST CHRYSTIE CANAL ST STATION ST D X ST X HESTER ST R P OW C ESSE P ANAL ST N R P P 6 QQW LUDL F ORCHA P ST SYTH E BROADWAY STATION P ST ALLEN LISPENARD ST CANAL ST STATION P ST ELDRIDGE FOR CANAL ST 11 P J M Z ISION ST RU VARICK ST DIV T WALKER ST 1 GERS ST P H ST ST H R ST ST R E ST E OTT ST ST OTT TE 4 ST -

For Immediate Release Going Downtown in History

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE GOING DOWNTOWN IN HISTORY: CHINATOWN NEW YORK CITY’S LANDMARKS TELL THE STORY OF A PEOPLE AND A CITY NEW YORK, NY – Not surprisingly, Chinatown New York City, one of the oldest neighborhoods in Manhattan, has several landmarks bearing the “oldest” title within its limits. The oldest Jewish cemetery can be found here, as can the oldest standing residence in New York City. Of course, Chinatown offers landmarks of a more modern breed as well. Where else in this country but Mott Street and its surrounding area can over 10 separate Asian cuisines be enjoyed? The neighborhood is a culinary capital, whose food reflects the rich and diverse history of immigrants from virtually every Eastern region in the world. Even born-and-raised New Yorkers are bound to learn something new from visiting Chinatown’s historic landmarks. A short walk through the neighborhood’s bustling streets is an explorer’s delight. After all, the history of Chinatown is the history of New York City itself, and history loves company. Following is a list of landmarks located in Chinatown New York City. • Chatham Square (cross streets) , also known as Kim Lau Square, is the site of the Kim Lau Memorial Arch. Located in the middle of the square, it was erected in 1962 in memory of the Chinese Americans who died in World War II. The square is named after the Earl of Chatham, William Pitt, who supported the American opposition to the Stamp Act, a tax on printed papers imposed on all American colonists by the British in 1765. -

32 DOMINICK STREET HOUSE, 32 Dominick Street, Manhattan Built C

Landmarks Preservation Commission March 27, 2012, Designation List 453 LP-2480 32 DOMINICK STREET HOUSE, 32 Dominick Street, Manhattan Built c. 1826; builder, Smith Bloomfield Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 5778, Lot 64 On June 28, 2011, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the 32 Dominick Street House and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 6). The hearing was duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. There were four speakers in favor of designation, including representatives of the New York Landmarks Conservancy, the Society for the Architecture of New York, the Historic Districts Council and the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. There were no speakers in opposition to designation. A letter in opposition to designation was received from the owner. Summary The 32 Dominck Street House was one of twelve Federal style brick row houses (nos. 28 to 50) built in c. 1826 on the south side of Dominick Street between Hudson and Varick Streets; and was one of the five houses (nos. 28 to 36) constructed by builder Smith Bloomfield. A secession of tenants lived in the house while owned by Bloomfield and it was sold by the executors of his estate to Mary McKindley in 1866. Her heirs conveyed it to John F. Wilson, a carpenter, in 1878. Wilson’s devisee sold it to the Church of Our Lady of Vilnius, which used it as a rectory. The church, located on Broome Street, was founded to serve the Lithuanian Catholic community and closed in 2007.