Effectiveness of Monitoring and Evaluation Activities At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inaugural Dr. Andrew Mlangeni Memorial Delivered by Minister Ronald Lamola at the University of South Africa on the 06Th of June 2021

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE AND CORRECTIONAL SERVICES Inaugural Dr. Andrew Mlangeni Memorial delivered by Minister Ronald Lamola at the University of South Africa on the 06th of June 2021 “Integrity and Revolutionary Ethics in Year of Charlotte [Manye]-Maxeke” Programme Director: Member of the Executive Council for the Gauteng Province Responsible for Sports Arts and Culture and Recreation Ms Mbali Hlophe Distinguished Guests Fellow panellists Principal and Vice Chancellor of the University of South Africa: Professor Puleng Lenkabula; The Council, Senate and Student Body of Unisa; Chairperson of Andrew and June Mlangeni Foundation: Professor Hlengiwe Mkhize our Deputy Minister responsible for Women, Youth, and People with Disabilities; Former Ambassador of South Africa to Poland Ms Febe Potigieter-Gqubule I have the honour of presenting the inaugural lecture today, the Premier of the home province of Baba Mlangeni, David Makhura could not be with us and thought it prudent that I be the one to take the baton. In the spirit of Thuma Mina I have obliged. Program Director, in preparing for this lecture, I thought if there was something we had come to learn from Andrew Mlangeni was the ability to speak truth to power no matter the costs. And it is for the reason that he remains a towering figure of history, who, while known to be very humble, is nevertheless part of the galaxy of the twentieth century revolutionaries whose legacies loom large over the horizon of South Africa’s history. “Some of our political leaders have become absolutely corrupt – they are no longer interested in improving the lives of our people. -

Annual Report 2018/19 Gauteng Deparment of Sport, Arts, Culture and Recreation: Vote 12

ANNUAL REPORT 2018/19 GAUTENG DEPARMENT OF SPORT, ARTS, CULTURE AND RECREATION: VOTE 12 GAUTENG PROVINCE Department of Sport, Arts, Culture & Recreation ANNUAL REPORT 2018/19 1 2018/19 ANNUAL REPORT 2018/19 ANNUAL REPORT GAUTENG DEPARMENT OF SPORT, ARTS, CULTURE AND RECREATION: VOTE 12 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART A: GENERAL INFORMATION ........................................................................ 8 1. DEPARTMENT GENERAL INFORMATION ...................................................................................9 2. LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS/ACRONYMS ...................................................................................... 10 3. FOREWORD BY THE MEC ........................................................................................................... 14 4. REPORT OF THE ACCOUNTING OFFICER ................................................................................ 16 5. STATEMENT OF RESPONSIBILITY AND CONFIRMATION OF ACCURACY ............................. 25 6. STRATEGIC OVERVIEW .............................................................................................................. 27 6.1 Vision ..................................................................................................................................... 27 6.2 Mission ...................................................................................................................................27 6.3 Values ................................................................................................................................... -

Export Directory As A

South African Government Provincial and Local Government Directory 2021-09-27 Table of Contents Provincial and Local Government Directory: Eastern Cape Municipalities ..................................................... 7 Alfred Nzo District Municipality ................................................................................................................................. 7 Amahlathi Local Municipality .................................................................................................................................... 7 Amathole District Municipality .................................................................................................................................. 7 Blue Crane Route Local Municipality......................................................................................................................... 8 Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality ........................................................................................................................ 8 Chris Hani District Municipality ................................................................................................................................. 8 Dr Beyers Naudé Local Municipality ....................................................................................................................... 9 Elundini Local Municipality ....................................................................................................................................... 9 Emalahleni Local Municipality ................................................................................................................................. -

06 June 2019

BUY ONE WINTER SPECIAL STARTS SPECIAL AVAILABLE TO EVERYONE!!! TOMBSTONE th & GET ONE 15 OF MAY 2019 VALID TILL 30 JUNE 2019 FREE Km/H Unveiling Package R500 off your next FREE DIGITAL R999 tombstone purchase !!! INVITATION 10 T-shirts KM/H * 50* Water bottles “make cents” 2 * Flowers R2000 Including a 7 Seater Car Quality Granite Tombstones at UNBEATABLE PRICES!!! (Upon Availability) NOW ON!!! HEAD OFFICE: SOWETO 9212 XORILE STREET, KILARNEY ORLANDO WEST 011 536 1165 / 082 802 4780 President Cyril Ramaphosa has shown PROVINCIAL COVERAGE 6 - 12 June 2019 commitment with the composition of a new Ministry of Employment and Labour which will address the challenge of President Ramaphosa reduced unemployment in the country. Hospital volunteer FREE his cabinet to 28 ministries COPY gets a car gift Weekly Mining mogul Daphne “We were pitted in a Mashile-Nkosi tough group I must be presented keys of honest,” Senong said. a white Nissan “This is was a great bakkie to thank Senong: Amajita platform for our play- Msimango and his ers to continue with selfless service to will grow their development...” the community President Cyril Ramaphosa has shown commitment with the composition of a new Ministry of Employment and from this WC Labour which will address the challenge of ...SEE STORY ON PAGE......2 unemployment in the country. ON PAGE....10 experience PAGE 12 City is aware of demolished illegal structures in Alexandra The City has ordered investigations to find out about who authorised the operation” STORY ON PAGE 2 JIET TACKLES YOUTH - TECHNICAL -

Covid-19 Regulatory Update 25May2020

Covid-19 Regulatory Update: 25 May 2020 CONTENTS CONFIRMED CASES .................................................. 2 HOUSING / HUMAN SETTLEMENTS ......................... 6 COURT ACTIONS ....................................................... 2 LEGAL PROFESSIONALS .......................................... 6 COURTS ...................................................................... 3 LOCKDOWN REGULATIONS ..................................... 7 CRIMINAL LAW AND PROCEDURE .......................... 3 SOCIAL SECURITY ..................................................... 8 DEEDS OFFICE ........................................................... 4 SPORT ......................................................................... 9 EDUCATION ................................................................ 4 TOURISM ..................................................................... 9 EMPLOYMENT LAW ................................................... 5 TRADE AND INDUSTRY ............................................. 9 FINANCIAL LAW .......................................................... 5 TRANSPORTATION .................................................. 10 HEALTH AND SAFETY ............................................... 6 TRAVEL ..................................................................... 10 Index to Covid-19 regulations and notices: https://juta.co.za/covid-19-legislation-update/2020/05/21/index/ Lexinfo Practice Management Alert This newsletter is published bi-monthly and focuses on issues such as client care, innovation, legal -

The African National Congress in Gauteng Has Congratulated

he African National Held annually the awards Armed with a wealth of experience Congress in Gauteng has recognise those who have played in the public sector, comrade Tcongratulated Comrade an active role in changing the role Ntombi is a seasoned activist who Ntombi Mekgwe for emerging as of women across sectors. It is one has close to 40 years-experience a winner in the Standard Bank of South Africa’s most prestigious serving in various structures Top Women Awards under the gender-empowerment events. of our movement during the Top Gender Empowered Public difficult period of apartheid and in Sector Leader category. Mekgwe, who received her democratic South Africa. She is accolade at a ceremony held in an ardent advocate of women’s The award is viewed as an Emperors Palace on Thursday, rights who is always fighting for affirmation of the quality and 15 August, is currently the the empowerment of women depth of women leaders within Speaker of the Gauteng across sectors of society. the ANC in Gauteng who continue Provincial Legislature and to serve tirelessly in various serves as a member of the ANC capacities across many fields, Gauteng Province’s Provincial • Mama Winnie honoured • ANC membership submission whether it be public or private Executive Committee and the underway sector, academia, business, etc. Provincial Working Committee. • Reflections of an ANC veteran • Budget Votes 2019/20 Lentswe la Gauteng / 1 @GautengANC @ancgauteng @ANCGauteng he honouring of Mama The ANC Caucus in the Gauteng “We are also convinced that It Winnie Madikizela-Mandela Provincial Legislature has was appropriate that a building Tthrough the renaming of welcomed the move by Unisa as a at a university with a long history one of the three University of historically significant step which is of student and youth activism be South Africa buildings after her is part of the transformation agenda. -

Journal of African Elections Special Issue South Africa’S 2014 Elections

remember to change running heads VOLUME 14 NO 1 i Journal of African Elections Special Issue South Africa’s 2014 Elections GUEST EDITORS Mcebisi Ndletyana and Mashupye H Maserumule This issue is published by the Electoral Institute for Sustainable Democracy in Africa (EISA) in collaboration with the Mapungubwe Institute for Strategic Reflection (MISTRA) and the Tshwane University of Technology ARTICLES BY Susan Booysen Sithembile Mbete Ivor Sarakinsky Ebrahim Fakir Mashupye H Maserumule, Ricky Munyaradzi Mukonza, Nyawo Gumede and Livhuwani L Ndou Shauna Mottiar Cherrel Africa Sarah Chiumbu Antonio Ciaglia Mcebisi Ndletyana Volume 14 Number 1 June 2015 i ii JOURNAL OF AFRICAN ELECTIONS Published by EISA 14 Park Road, Richmond Johannesburg South Africa P O Box 740 Auckland Park 2006 South Africa Tel: +27 (0) 11 381 6000 Fax: +27 (0) 11 482 6163 e-mail: [email protected] ©EISA 2015 ISSN: 1609-4700 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher Printed by: Corpnet, Johannesburg Cover photograph: Reproduced with the permission of the HAMILL GALLERY OF AFRICAN ART, BOSTON, MA, USA www.eisa.org.za remember to change running heads VOLUME 14 NO 1 iii EDITOR Denis Kadima, EISA, Johannesburg MANAGING AND COPY EDITOR Pat Tucker EDITORIAL BOARD Chair: Denis Kadima, EISA, Johannesburg Jørgen Elklit, Department of Political Science, University -

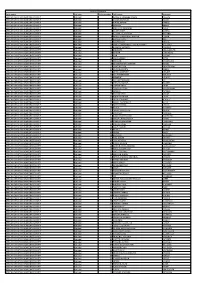

Party Name List Type Order Number Full Names Surname AFRICAN

NPE2019 Party name List type Order number Full names Surname AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 1 DULTON KEITH ADAMS AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 2 TUMISHO LESIBA MOLOKOMME AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 3 ABSALOM MAKHAZA SITHOLE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 4 ROBERT ANDREAS BENDER AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 5 LINDA MERIDY YATES AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 6 MARITI JOHN MOFOKENG AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 7 PRUDENCE VUYISWA MHLONGO AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 8 BERNICE PEARL OSA AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 9 IVAN JARDINE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 10 CHRISTIAN KARL PETER ROHLSSEN AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 11 NOSIZWE ABADA AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 12 BRIAN SIBUSISO MSIBI AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 13 BRENDON GOVENDER AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 14 TAMBO ANDREW MOKOENA AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 15 KHUTSO MOKGEHLE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 16 BEAUTY DELIWE NGWENYA AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 17 NORMAN FANA MKHONZA AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 18 DIMAKATSO FRIDAH RAMABINA AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 19 WILLEM MESHARK VAN WYK AFRICAN CHRISTIAN -

Provincial Seats Assigned

GAUTENG PROVINCE LIST Party List Rank ID Name Surname AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 1 6207105173087 DULTON KEITH ADAMS AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS Provincial: Gauteng 1 6802225585085 MALEMOLLA DAVID MAKHURA AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS Provincial: Gauteng 2 6809045469085 ANDREK LESUFI AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS Provincial: Gauteng 3 6606080789082 NOMANTU RALEHOKO AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS Provincial: Gauteng 4 7912265221084 LEBOGANG ISAAC MAILE AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS Provincial: Gauteng 5 6504020433087 NONHLANHLA FAITH MAZIBUKO AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS Provincial: Gauteng 6 6410210679085 LENTHENG HELEN MEKGWE AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS Provincial: Gauteng 7 8205305652080 MATOME KOPANO CHILOANE AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS Provincial: Gauteng 8 7006066056086 MPHO PARKS FRANKLYN TAU AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS Provincial: Gauteng 9 7301040721081 THULISWA WINLOVE KHAWE AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS Provincial: Gauteng 10 7501255338089 KGOSIENTSO DAVID RAMOKGOPA AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS Provincial: Gauteng 11 8210085755087 BOITUMELO EZRA LETSOALO AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS Provincial: Gauteng 12 6607175370085 MAPITI DAVID MATSENA AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS Provincial: Gauteng 13 6701210229081 REFILOE JOHANNAH KEKANA AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS Provincial: Gauteng 14 5708250877084 ALPHINA ANNA NDLOVANA AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS Provincial: Gauteng 15 8601315914082 LESEGO ELLIS MAKHUBELA AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS Provincial: Gauteng 16 7511025445080 BANDILE EDGAR WALLACE MASUKU AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS Provincial: Gauteng 17 6209040830086 -

Party Name List Type Order Number Idnumber Full Names Surname

NPE2019 Party name List type Order number IDNumber Full names Surname AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 1 6207105173087 DULTON KEITH ADAMS AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 2 7302225311086 TUMISHO LESIBA MOLOKOMME AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 3 6904205339085 ABSALOM MAKHAZA SITHOLE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 4 6610065081085 ROBERT ANDREAS BENDER AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 5 6302220199081 LINDA MERIDY YATES AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 6 8006295830086 MARITI JOHN MOFOKENG AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 7 6608280310081 PRUDENCE VUYISWA MHLONGO AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 8 7810230406089 BERNICE PEARL OSA AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 9 5403065155088 IVAN JARDINE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 10 7111055228082 CHRISTIAN KARL PETER ROHLSSEN AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 11 7403090279083 NOSIZWE ABADA AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 12 7604205477088 BRIAN SIBUSISO MSIBI AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 13 7805075112081 BRENDON GOVENDER AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 14 6504065973088 TAMBO ANDREW MOKOENA AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 15 8910040628085 KHUTSO MOKGEHLE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Provincial: Gauteng 16 8404150763080 BEAUTY DELIWE NGWENYA AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC -

Candidate Lists

Local Government Elections 2006 Candidate Lists Eastern Cape - DC10 - Cacadu [Western District] AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY PR List - DC Voted 1 CALITZ, MATTHEW BERNARD 2 LOUW, STIFANIS SEBASTIAAN WALTERS 3 MBAMBANI, FIKILE CHRISTOPHER 4 MAC TAGGART, DUNCAN DONALD AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS PR List - DC Voted 1 MVOKO, GERALD MLUNGISI 2 KEKANA, KHUNJUZWA EUNICE 3 DE VOS, DEON WESLEY SAM 4 LWANE, VUMILE GLADMAN 5 PLAATJIES, HEIDIE LU-ANN 6 FAXI, PHINDILE PATRICK 7 PIETERS, NONKQUBELA NTOMBOXOLO 8 WILLIAMS, OTTO MLINDI 9 VELEZANTSI, NDILEKA 10 DU PLESSIS, YVETTE MARGUERITA 11 KEPE, NOZIPHO VALENTIA 12 MBOLEKWA, KHULULEKILE CECIL 13 MASELANA, THOBEKA SUSAN 14 HOKO, VUYISILE VINCENT 15 JANTJIES, BENDIM TIRONE 16 MBEKI, MCIBOSI DAVID DEMOCRATIC ALLIANCE/DEMOKRATIESE ALLIANSIE PR List - DC Voted 1 NORTJE, ANDREAS LOUWRENS 2 VAN LINGEN, ELIZABETH CHRISTINA 3 JONES PHILLIPSON, CECIL PETER 4 COENRAAD, WILMA MILINDA 5 WHISSON, MICHAEL GEORGE INDEPENDENT DEMOCRATS PR List - DC Voted 1 LIBERTY, PETRONELLA JO-ANNE 2 KETTLEDAS, SILASTINE WAYNE PAN AFRICANIST CONGRESS OF AZANIA PR List - DC Voted 1 KOBA, MLONDOLOZI 2 GODLO, THABO ELGIN 3 BULUTA, ZALISA PATRICK UNITED DEMOCRATIC MOVEMENT PR List - DC Voted 1 DZEDZE, THANDUXOLO AUBREY Eastern Cape - DC12 - Amatole [Amatola District] AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY PR List - DC Voted 1 MONTES, VERONICA Page 1 of 122 Local Government Elections 2006 Candidate Lists AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS PR List - DC Voted 1 MLONDLENI, NTOMBEKAYA 2 MTONGANA, MTOBELE 3 SINUKA, NIKELWA ELIZABETH 4 THANDELA, NIKIWE -

Party Name List Type Order Number Full Names Surname AFRICAN

National NPE2019 Party name List type Order number Full names Surname AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 1 KENNETH RASELABE JOSEPH MESHOE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 2 STEVEN NICHOLAS SWART AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 3 WAYNE MAXIM THRING AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 4 NOSIZWE ABADA AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 5 MOKHETHI RAYMOND TLAELI AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 6 JO-ANN MARY DOWNS AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 7 KEITUMETSE PATRICIA MATANTE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 8 GRANT CHRISTOPHER RONALD HASKIN AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 9 BERNICE PEARL OSA AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 10 MZUKISI ELIAS DINGILE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 11 DAVID EUGENE MOSES JOSHUA BARUTI NTSHABELE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 12 BONGANI MAXWELL KHANYILE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 13 ANNIRUTH KISSOONDUTH AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 14 MARVIN CHRISTIANS AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 15 IVAN JARDINE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 16 LINDA MERIDY YATES AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 17 MONGEZI MABUNGANI AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 18 KGOMOTSO WELHEMINAH TISANE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 19 LANCE PATRICK GROOTBOOM AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 20 MARIE ELIZABETH SUKERS AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 21 MPHO LAWRENCE CHAUKE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY