Press Kit Jawlensky. the Landscape of the Face

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elisabeth Epstein: Moscow–Munich–Paris–Geneva, Waystations of a Painter and Mediator of the French-German Cultural Transfer

chapter 12 Elisabeth Epstein: Moscow–Munich–Paris–Geneva, Waystations of a Painter and Mediator of the French-German Cultural Transfer Hildegard Reinhardt Abstract The artist Elisabeth Epstein is usually mentioned as a participant in the first Blaue Reiter exhibition in 1911 and the Erster Deutscher Herbstsalon in 1913. Living in Munich after 1898, Epstein studied with Anton Ažbe, Wassily Kandinsky, and Alexei Jawlensky and participated in Werefkin’s salon. She had already begun exhibiting her work in Paris in 1906 and, after her move there in 1908, she became the main facilitator of the artistic exchange between the Blue Rider artists and Sonia and Robert Delaunay. In the 1920s and 1930s she was active both in Geneva and Paris. This essay discusses the life and work of this Russian-Swiss painter who has remained a peripheral figure despite her crucial role as a mediator of the French-German cultural transfer. Moscow and Munich (1895–1908) The special attraction that Munich and Paris exerted at the beginning of the twentieth century on female Russian painters such as Alexandra Exter, Sonia Delaunay, Natalia Goncharova, and Olga Meerson likewise characterizes the biography of the artist Elisabeth Epstein née Hefter, the daughter of a doc- tor, born in Zhytomir/Ukraine on February 27, 1879. After the family’s move to Moscow, she began her studies, which continued from 1895 to 1897, with the then highly esteemed impressionist figure painter Leonid Pasternak.1 Hefter’s marriage, in April 1898, to the Russian doctor Miezyslaw (Max) Epstein, who had a practice in Munich, and the birth of her only child, Alex- ander, in March 1899, are the most significant personal events of her ten-year period in Bavaria’s capital. -

The Creative Output of Alexej Von Jawlensky (Torzhok, Russia, 1864

The creative output of Alexej von Jawlensky (Torzhok, Russia, 1864 - Wiesbaden, Germany, 1941) is dened by a simultaneously visual and spiritual quest which took the form of a recurring, almost ritual insistence on a limited number of pictorial motifs. In his memoirs the artist recalled two events which would be crucial for this subsequent evolution. The rst was the impression made on him as a child when he saw an icon of the Virgin’s face reveled to the faithful in an Orthodox church that he attended with his family. The second was his rst visit to an exhibition of paintings in Moscow in 1880: “It was the rst time in my life that I saw paintings and I was touched by grace, like the Apostle Paul at the moment of his conversion. My life was totally transformed by this. Since that day art has been my only passion, my sancta sanctorum, and I have devoted myself to it body and soul.” Following initial studies in art in Saint Petersburg, Jawlensky lived and worked in Germany for most of his life with some periods in Switzerland. His arrival in Munich in 1896 brought him closer contacts with the new, avant-garde trends while his exceptional abilities in the free use of colour allowed him to achieve a unique synthesis of Fauvism and Expressionism in a short space of time. In 1909 Jawlensky, his friend Kandinsky and others co-founded the New Association of Artists in Munich, a group that would decisively inuence the history of modern art. Jawlensky also participated in the activities of Der Blaue Reiter [the Blue Rider], one of the fundamental collectives for the formulation of the Expressionist language and abstraction. -

Impressionist & Modern

Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I 10 October 2019 Lot 8 Lot 2 Lot 26 (detail) Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I Thursday 10 October 2019, 5pm BONHAMS ENQUIRIES PHYSICAL CONDITION IMPORTANT INFORMATION 101 New Bond Street London OF LOTS IN THIS AUCTION The United States Government London W1S 1SR India Phillips PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS NO has banned the import of ivory bonhams.com Global Head of Department REFERENCE IN THIS CATALOGUE into the USA. Lots containing +44 (0) 20 7468 8328 TO THE PHYSICAL CONDITION OF ivory are indicated by the VIEWING [email protected] ANY LOT. INTENDING BIDDERS symbol Ф printed beside the Friday 4 October 10am – 5pm MUST SATISFY THEMSELVES AS lot number in this catalogue. Saturday 5 October 11am - 4pm Hannah Foster TO THE CONDITION OF ANY LOT Sunday 6 October 11am - 4pm Head of Department AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 14 PRESS ENQUIRIES Monday 7 October 10am - 5pm +44 (0) 20 7468 5814 OF THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS [email protected] Tuesday 8 October 10am - 5pm [email protected] CONTAINED AT THE END OF THIS Wednesday 9 October 10am - 5pm CATALOGUE. CUSTOMER SERVICES Thursday 10 October 10am - 3pm Ruth Woodbridge Monday to Friday Specialist As a courtesy to intending bidders, 8.30am to 6pm SALE NUMBER +44 (0) 20 7468 5816 Bonhams will provide a written +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 25445 [email protected] Indication of the physical condition of +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 Fax lots in this sale if a request is received CATALOGUE Julia Ryff up to 24 hours before the auction Please see back of catalogue £22.00 Specialist starts. -

Die Brücke Der Blaue Reiter Expressionists

THE SAVAGES OF GERMANY DIE BRÜCKE DER BLAUE REITER EXPRESSIONISTS 22.09.2017– 14.01.2018 The exhibition The Savages of Germany. Die Brücke and Der DIE BRÜCKE (“The Bridge” in English) was a German artistic group founded in Blaue Reiter Expressionists offers a unique chance to view the most outstanding works of art of two pivotal art groups of 1905 in Dresden. The artists of Die Brücke abandoned visual impressions and the early 20th century. Through the oeuvre of Ernst Ludwig idyllic subject matter (typical of impressionism), wishing to describe the human Kirchner, Emil Nolde, Wassily Kandinsky, August Macke, Franz Marc, Alexej von Jawlensky and others, the exhibition inner world, full of controversies, fears and hopes. Colours in their paintings tend focuses on the innovations introduced to the art scene by to be contrastive and intense, the shapes deformed, and the details enlarged. expressionists. Expressionists dedicated themselves to the Besides the various scenes of city life, another common theme in Die Brücke’s study of major universal themes, such as the relationship between man and the universe, via various deeply personal oeuvre was scenery: when travelling through the countryside, the artists saw an artistic means. opportunity to depict man’s emotional states through nature. The group disbanded In addition to showing the works of the main authors of German expressionism, the exhibition attempts to shed light in 1913. on expressionism as an influential artistic movement of the early 20th century which left its imprint on the Estonian art DER BLAUE REITER (“The Blue Rider” in English) was another expressionist of the post-World War I era. -

Mehr Mode Rn E Fü R D As Le N Ba Ch Ha Us Die

IHR LENBACHHAUS.DE KUNSTMUSEUM IN MÜNCHEN MEHR MEHR FÜR DAS MODERNE LENBACHHAUS LENBACHHAUS DIE NEUERWERBUNGEN IN DER SAMMLUNG BLAUER REITER 13 OKT 2020 BIS 7 FEB 2021 Die Neuerwerbungen in der Sammlung Blauer Reiter 13. Oktober 2020 bis 7. Februar 2021 MEHR MODERNE FÜR DAS LENBACHHAUS ie weltweit größte Sammlung zur Kunst des Blauen Reiter, die das Lenbachhaus sein Eigen nennen darf, verdankt das Museum in erster Linie der großzügigen Stiftung von Gabriele Münter. 1957 machte die einzigartige Schenkung anlässlich des 80. Geburtstags der D Künstlerin die Städtische Galerie zu einem Museum von Weltrang. Das herausragende Geschenk umfasste zahlreiche Werke von Wassily Kandinsky bis 1914, von Münter selbst sowie Arbeiten von Künstlerkolleg*innen aus dem erweiterten Kreis des Blauen Reiter. Es folgten bedeutende Ankäufe und Schen- kungen wie 1965 die ebenfalls außerordentlich großzügige Stiftung von Elly und Bernhard Koehler jun., dem Sohn des wichtigen Mäzens und Sammlers, mit Werken von Franz Marc und August Macke. Damit wurde das Lenbachhaus zum zentralen Ort der Erfor- schung und Vermittlung der Kunst des Blauen Reiter und nimmt diesen Auftrag seit über sechs Jahrzehnten insbesondere mit seiner August Macke Ausstellungstätigkeit wahr. Treibende Kraft Reiter ist keinesfalls abgeschlossen, ganz im KINDER AM BRUNNEN II, hinter dieser Entwicklung war Hans Konrad Gegenteil: Je weniger Leerstellen verbleiben, CHILDREN AT THE FOUNTAIN II Roethel, Direktor des Lenbachhauses von desto schwieriger gestaltet sich die Erwer- 1956 bis 1971. Nach seiner Amtszeit haben bungstätigkeit. In den vergangenen Jahren hat 1910 sich auch Armin Zweite und Helmut Friedel sich das Lenbachhaus bemüht, die Sammlung Öl auf Leinwand / oil on canvas 80,5 x 60 cm erfolgreich für die Erweiterung der Sammlung um diese besonderen, selten aufzufindenden FVL 43 engagiert. -

Exhibit Order Form

40% Exhibit Discount Valid Until April 13, 2021 University of Chicago Press Books are for display only. Order on-site and receive FREE SHIPPING. EX56775 / EX56776 Ship To: Name Address Shipping address on your business card? City, State, Zip Code STAPLE IT HERE Country Email or Telephone (required) Return this form to our on-site representative. OR Mail/fax orders with payment to: Buy online: # of Books: _______ Chicago Distribution Center Visit us at www.press.uchicago.edu. Order Department To order books from this meeting online, 11030 S. Langley Ave go to www.press.uchicago.edu/directmail Subtotal Chicago, IL 60628 and use keycode EX56776 to apply the USA 40% exhibit Fax: 773.702.9756 *Sales Tax Customer Service: 1.800.621.2736 **Shipping and Ebook discount: Most of the books published by the University of Chicago Press are also Handling available in e-book form. Chicago e-books can be bought and downloaded from our website at press.uchicago.edu. To get a 20% discount on e-books published by the University of Chicago Press, use promotional code UCPXEB during checkout. (UCPXEB TOTAL: only applies to full-priced e-books (All prices subject to change) For more information about our journals and to order online, visit *Shipments to: www.journals.uchicago.edu. Illinois add 10.25% Indiana add 7% Massachusets add 6.25% California add applicable local sales tax Washington add applicable local sales tax College Art Association New York add applicable local sales tax Canada add 5% GST (UC Press remits GST to Revenue Canada. Your books will / February 10 - 13, 2021 be shipped from inside Canada and you will not be assessed Canada Post's border handling fee.) Payment Method: Check Credit Card ** If shipping: $6.50 first book Visa MasterCard American Express Discover within U.S.A. -

Alexander Von Salzmann 1874 Tbilisi (Georgia) – 1934 Leysin (Switzerland)

Alexander von Salzmann 1874 Tbilisi (Georgia) – 1934 Leysin (Switzerland) A native of Tbilisi, Alexander von Salzmann was born into a cultivated family and received a thorough upbringing and early training in art, music and drama. Fluent in four languages – Russian, German, English and French – he was often described as sensitive and amiable but at the same time reputed to be unreliable and indolent. He trained as a painter in Moscow, later moving to Munich where he enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in 1898 to study under Franz Stuck. Two years later, Wassily Kandinsky joined the same painting class. A large number of Russian artists were living and working in Munich around the turn of the twentieth century. Kandinsky, who had a strong network of contacts within Schwabing’s vibrant art world, introduced Salzmann to one of his many Russian contacts – the painter Alexej von Jawlensky. Jawlensky was romantically involved with Marianne von Werefkin, a Russian aristocrat and painter who had made the decision to interrupt her own artistic Alexander von Salzmann, Self-portrait, career to further Jawlensky’s painting. In her elegant Munich 1905 apartment Werefkin hosted a Salon which grew to be a hub of literary and artistic exchange. Salzmann soon became a regular visitor and before long was making advances to his hostess. Despite a significant age difference, they became lovers but the affair ended abruptly in 1905. Six years later Kandinsky, Jawlensky and Werefkin formed The Blue Rider, one of the leading artists’ groups of the twentieth century. Like many other Munich-based, emerging artists of the period Salzmann earned his living as an illustrator for the magazine Jugend. -

Max Beckmann Alexej Von Jawlensky Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Fernand Léger Emil Nolde Pablo Picasso Chaim Soutine

MMEAISSTTEERRWPIECREKSE V V MAX BECKMANN ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY ERNST LUDWIG KIRCHNER FERNAND LÉGER EMIL NOLDE PABLO PICASSO CHAIM SOUTINE GALERIE THOMAS MASTERPIECES V MASTERPIECES V GALERIE THOMAS CONTENTS MAX BECKMANN KLEINE DREHTÜR AUF GELB UND ROSA 1946 SMALL REVOLVING DOOR ON YELLOW AND ROSE 6 STILLEBEN MIT WEINGLÄSERN UND KATZE 1929 STILL LIFE WITH WINE GLASSES AND CAT 16 ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY STILLEBEN MIT OBSTSCHALE 1907 STILL LIFE WITH BOWL OF FRUIT 26 ERNST LUDWIG KIRCHNER LUNGERNDE MÄDCHEN 1911 GIRLS LOLLING ABOUT 36 MÄNNERBILDNIS LEON SCHAMES 1922 PORTRAIT OF LEON SCHAMES 48 FERNAND LÉGER LA FERMIÈRE 1953 THE FARMER 58 EMIL NOLDE BLUMENGARTEN G (BLAUE GIEßKANNE) 1915 FLOWER GARDEN G (BLUE WATERING CAN) 68 KINDER SOMMERFREUDE 1924 CHILDREN’S SUMMER JOY 76 PABLO PICASSO TROIS FEMMES À LA FONTAINE 1921 THREE WOMEN AT THE FOUNTAIN 86 CHAIM SOUTINE LANDSCHAFT IN CAGNES ca . 1923-24 LANDSCAPE IN CAGNES 98 KLEINE DREHTÜR AUF GELB UND ROSA 1946 SMALL REVOLVING DOOR ON YELLOW AND ROSE MAX BECKMANN oil on canvas Provenance 1946 Studio of the Artist 60 x 40,5 cm Hanns and Brigitte Swarzenski, New York 5 23 /8 x 16 in. Private collection, USA (by descent in the family) signed and dated lower right Private collection, Germany (since 2006) Göpel 71 2 Exhibited Busch Reisinger Museum, Cambridge/Mass. 1961. 20 th Century Germanic Art from Private Collections in Greater Boston. N. p., n. no. (title: Leaving the restaurant ) Kunsthalle, Mannheim; Hypo Kunsthalle, Munich 2 01 4 - 2 01 4. Otto Dix und Max Beckmann, Mythos Welt. No. 86, ill. p. 156. -

Kees Van Dongen Max Ernst Alexej Von Jawlensky Otto Mueller Emil Nolde Max Pechstein Oskar Schlemmer

MASTERPIECES VIII KEES VAN DONGEN MAX ERNST ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY OTTO MUELLER EMIL NOLDE MAX PECHSTEIN OSKAR SCHLEMMER GALERIE THOMAS MASTERPIECES VIII GALERIE THOMAS CONTENTS ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY MAX ERNST STILL LIFE WITH JUG AND APPLES 1908 6 FEMMES TRAVERSANT UNE RIVIÈRE EN CRIANT 1927 52 PORTRAIT C. 191 616 ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY MAX PECHSTEIN HOUSE WITH PALM TREE 191 4 60 INTERIEUR 1922 22 OSKAR SCHLEMMER EMIL NOLDE ARCHITECTURAL SCULPTURE R 191 9 68 YOUNG FAMILY 1949 30 FIGURE ON GREY GROUND 1928 69 KEES VAN DONGEN ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY PORTRAIT DE FEMME BLONDE AU CHAPEAU C. 191 2 38 WOMAN IN RED BLOUSE 191 1 80 EMIL NOLDE OTTO MUELLER LANDSCAPE (PETERSEN II) 1924 44 PAIR OF RUSSIAN GIRLS 191 9 88 4 5 STILL LIFE WITH JUG AND APPLES 1908 ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY oil on cardboard Provenance 1908 Studio of the artist 23 x 26 3/4 in. Adolf Erbslöh signed lower right, Galerie Otto Stangl, Munich signed in Cyrillic and Private collection dated lower left Galerie Thomas, Munich Private collection Jawlensky 21 9 Exhibited Recorded in the artist’s Moderne Galerie, Munich 191 0. Neue Künstlervereinigung, II. Ausstellung. No. 45. photo archive with the title Galerie Paul Cassirer, Berlin 1911 . XIII. Jahrgang, VI. Ausstellung. ‘Nature morte’ Galerie Otto Stangl, Munich 1948. Alexej Jawlensky. Image (leaflet). Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris; Haus der Kunst Munich, 1966. Le Fauvisme français et les débuts de l’Expressionisme allemand. No. 164, ill. p.233. Ganserhaus, Wasserburg 1979. Alexej von Jawlensky – Vom Abbild zum Urbild. No. 18, ill. p.55. -

Alexej Jawlensky's Pain

“. I CAME TO UNDERSTAND HOW TO TRANSLATE NATURE INTO COLOUR ACCORDING TO THE FIRE IN MY SOUL”: ALEXEJ JAWLENSKY’S PAINTING TECHNIQUE IN HIS MUNICH OEUVRE Ulrike Fischer, Heike Stege, Daniel Oggenfuss, Cornelia Tilenschi, Susanne Willisch and Iris Winkelmeyer ABSTRACT ingly, technological and analytical assessment is commissioned The Russian painter Alexej Jawlensky, who worked in Munich between to complement stylistic judgement with an objective critique 1896 and 1914, was an important representative of Expressionism and of materials, painting technique and the condition of question- abstract art in Germany. He was involved with the artistic group Der Blaue Reiter, whose members shared not only ideas about art but also an able items. The manifold particularities a painting may reveal interest in questions of painting technique and painting materials. This in respect to painting support, underdrawing, pigments, bind- paper aims to illuminate the working process of Jawlensky through ing media, paint application and consistency, later changes research into the characteristics of his painting technique. It examines and restorations, ageing phenomena, etc., present a wealth of the paint supports and painting materials in specific works of art from information and often a new understanding of the object. This Jawlensky’s Munich period. This technical examination, together with the evaluation of written sources reveals the manifold artistic and technologi- technology-based perspective may even significantly influence cal influences that contributed to the development and peculiarities of the art historical judgement, such as in the case of altered signa- Jawlensky’s art. Comparisons with selected works by Wassily Kandinsky ture or changes in appearance as a result of previous restoration and Gabriele Münter show the strong influence Jawlensky’s painting tech- treatments. -

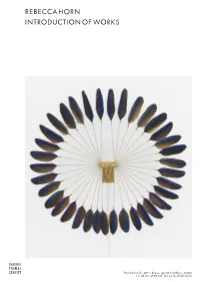

Rebecca Horn Introduction of Works

REBECCA HORN INTRODUCTION OF WORKS • Parrot Circle, 2011, brass, parrot feathers, motor t = 28 cm, Ø 67 cm | d = 11 in, Ø 26 1/3 in Since the early 1970s, Rebecca Horn (born 1944 in Michelstadt, Germany) has developed an autonomous, internationally renowned position beyond all conceptual, minimalist trends. Her work ranges from sculptural en- vironments, installations and drawings to video and performance and manifests abundance, theatricality, sensuality, poetry, feminism and body art. While she mainly explored the relationship between body and space in her early performances, that she explored the relationship between body and space, the human body was replaced by kinetic sculptures in her later work. The element of physical danger is a lasting topic that pervades the artist’s entire oeuvre. Thus, her Peacock Machine—the artist’s contribu- tion to documenta 7 in 1982—has been called a martial work of art. The monumental wheel expands slowly, but instead of feathers, its metal keels are adorned with weapon-like arrowheads. Having studied in Hamburg and London, Rebecca Horn herself taught at the University of the Arts in Berlin for almost two decades beginning in 1989. In 1972 she was the youngest artist to be invited by curator Harald Szeemann to present her work in documenta 5. Her work was later also included in documenta 6 (1977), 7 (1982) and 9 (1992) as well as in the Venice Biennale (1980; 1986; 1997), the Sydney Biennale (1982; 1988) and as part of Skulptur Projekte Münster (1997). Throughout her career she has received numerous awards, including Kunstpreis der Böttcherstraße (1979), Arnold-Bode-Preis (1986), Carnegie Prize (1988), Kaiserring der Stadt Goslar (1992), ZKM Karlsruhe Medienkunstpreis (1992), Praemium Imperiale Tokyo (2010), Pour le Mérite for Sciences and the Arts (2016) and, most recently, the Wilhelm Lehmbruck Prize (2017). -

UNSEEN WORKS of the EUROPEAN AVANT-GARDE An

Press Release July 2020 Mitzi Mina | [email protected] | Melica Khansari | [email protected] | Matthew Floris | [email protected] | +44 (0) 207 293 6000 UNSEEN WORKS OF THE EUROPEAN AVANT-GARDE An Outstanding Family Collection Assembled with Dedication Over Four Decades To Be Offered at Sotheby’s London this July Over 40 Paintings, Sculpture & Works on Paper Led by a Rare Cubist Work by Léger & an Intimate Picasso Portrait of his Secret Lover Marie-Thérèse Pablo Picasso | Fernand Léger | Alberto Giacometti | Wassily Kandinsky | Lyonel Feininger | August Macke | Alexej von Jawlensky | Jacques Lipchitz | Marc Chagall | Henry Moore | Henri Laurens | Jean Arp | Albert Gleizes Helena Newman, Worldwide Head of Sotheby’s Impressionist & Modern Art Department, said: “Put together with passion and enjoyed over many years, this private collection encapsulates exactly what collectors long for – quality and rarity in works that can be, and have been, lived with and loved. Unified by the breadth and depth of art from across Europe, it offers seldom seen works from the pinnacle of the Avant-Garde, from the figurative to the abstract. At its core is an exceptionally beautiful 1931 portrait of Picasso’s lover, Marie-Thérèse, an intimate glimpse into their early days together when the love between the artist and his most important muse was still a secret from the world.” The first decades of the twentieth century would change the course of art history for ever. This treasure-trove from a private collection – little known and rarely seen – spans the remarkable period, telling its story through the leading protagonists, from Fernand Léger, Pablo Picasso and Alberto Giacometti to Wassily Kandinsky, Lyonel Feininger and Alexej von Jawlensky.