Contact: Terms Governing Use and Reproduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Record-Mirror-1978-1

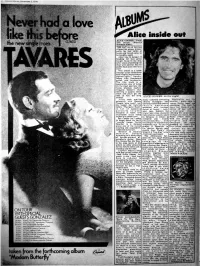

Record Mora, December 2. 1978 Alice inside out rr ALICE COOPER: 'From The Inside' (Warner Brothers K5677) t , t- THE BAT out of hell has clipped his wings, thrown sz away his last bottle of 1 booze and vowed never to be nAughty again. s Alice was In danger of A heading for that great boogie house In the sky, after years of pickling his Si liver with alcohol. But he pulled back and went on a cure. This album Is a loose a. concept of his reflections . and hospital experiences. t Apocalyptic tracks, , -k heavy with thunderous , II guitar and keyboards. The title track is a panoramic view of being on the road and how the booze troubles started. Imagine 'School's Out' meeting a quality disco track and you'll get the 'idea of how the song on the wagon sounds. ALICE COOPER: Alice now works many assorted seventies Highlights are the primarily with Bernie albums Rundgren has cocktail - piano intro to Taupin, who hasn't lost cleverly fused mid -sixties 'never Never Land' and his talent for incisive idyllic American emotional 'The Verb To lyrics. 'The Quiet Room' melodies with various Love' but 'Hello It's Me' Is full of opposing forms of heavy - rock. comes off best with Its parallels between soul; jazz, Eastern In- archetypal chorus thoughts of home and trigue and even modern utilising the vocal talents frustration about being Instrumental pieces akin of Hall and Oates, Stevie n M locked in a padded cell. to Debussy to create a Nicks (when she's not But Cooper isn't going complete 'pop - sound with her group she's to forget about his early encyclopaedia', and alright) and Rick "weirdo" Image. -

SOME KIND of WAY out by BARBARA GORMAN A

SOME KIND OF WAY OUT by BARBARA GORMAN A thesis submitted to the Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts Graduate Program in Creative Writing written under the direction of Prof. Lauren Grodstein and approved by ______________________________ Prof. Lauren Grodstein Camden, New Jersey October 2013 i THESIS ABSTRACT SOME KIND OF WAY OUT By BARBARA GORMAN Thesis Director: Prof. Lauren Grodstein Sixteen-year-old classic rock and blues guitar aficionado Drew Gilmore and his fourteen- year-old sister Cori have been helping their divorced mother Michelle cope with her advanced multiple sclerosis for the past two years to the best of their ability, but the severe sensory pain and uncontrollable muscle spasms have left Michelle, a former grocery store cashier, confined to a wheelchair most days and unable to sleep most nights. A concerned social worker and a few school staff members have begun to question whether Drew and Cori’s needs are being met at home. Drew is resistant and at times hostile toward any suggestions that Michelle may be unable to take care of them, insisting that he and Cori have plenty of help from family and friends in their working class neighborhood of Gloucester City, New Jersey, and that their father Frank, a prison guard who lives in Trenton, New Jersey, with his new wife and toddler son, does the grocery shopping and takes care of the bills. But Drew knows that things at home are far from okay, forcing things at school to a breaking point. -

A Newwave of Rock Fever

10 BERKELEY BARB, Jan. 20-26, 1978 PLATTERS A NewWave Of Rock Fever Bette the brassy babe becomes by Michael Snyder Cross Lou Reed's rock 'n' roll LOL CREME/KEVIN GODLEY heart. We saw the corpse kick Consequences (Mercury): a fragile flower. Bessie Smith's ing and thrashing throughout Mammoth, three-record boxed "Empty Bed Blues," the Ro- Welcome to a fresh start. A nettes' "Paradise," a duet with new wave, as it were. Nonse- Winterland at the Pistols' show set, directed by two former mem last weekend. We heatd and felt bers of 10 CC. Weird synthetic Tom Waits on "I Never Talk To quiturs aside, 1978's product has Strangers" (the same take that's yet to hit the racks, so we're the beat. ' Born again, brothers noises, two or three fair-to- sisters... middlin' songs (one with the on Waits' latest LP, Foreign indulging in a quasi-retrospec and Affairs) and "La Vie En Rose." tive of a few recorded goods that « * * silky voice of Sarah Vaughn) The Line and tons of garbled rapping by Midler's strongest record since went unheralded in these pages AEROSMITH-Draw her first, which was arranged by during '77. No sense in another (Columbia): They drew it, but British satirist Peter Cook. It's didn't snort it. The title cut a fascinating demo for Creme Super-Wimp Barry Manilow. His Tops-Qf-The-Year list, anyway. they absence makes Broken Blossom You can see Blair Jackson's poll is as awesome as the Stones' and Godley's instrumental inven tion, the Gizmo, in the same way twice as good by default. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 08/09/2016 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 08/09/2016 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Crazy - Patsy Cline Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Don't Stop Believing - Journey Love Yourself - Justin Bieber Shake It Off - Taylor Swift Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond My Girl - The Temptations Like I'm Gonna Lose You - Meghan Trainor Girl Crush - Little Big Town Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Ex's & Oh's - Elle King Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Black Velvet - Alannah Myles Let It Go - Idina Menzel Me Too - Meghan Trainor Baby Got Back - Sir Mix-a-Lot EXPLICIT Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals H.O.L.Y. - Florida Georgia Line Hello - Adele Sweet Home Alabama - Lynyrd Skynyrd When We Were Young - Adele Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Jackson - Johnny Cash Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Summer Nights - Grease Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Unchained Melody - The Righteous Brothers Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Livin' On A Prayer - Bon Jovi Can't Stop The Feeling - Justin Timberlake Piano Man - Billy Joel I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys All Of Me - John Legend Turn The Page - Bob Seger These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley My Way - Frank Sinatra (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Love Shack - The B-52's 7 Years - Lukas Graham Wannabe - Spice Girls A Whole New World - -

1 Most Requested 120 Songs, 7:43:33 Total Time, 489.1 MB

#1 Most Requested 120 songs, 7:43:33 total time, 489.1 MB Name Time Album Artist Ain't No Other Man 3:48 Ain't No Other Man - Single Christina Aguilera All My Life 3:42 Now 1 K-Ci & JoJo All Star 3:21 Now That's What I Call Music! Vol. 3 Smash Mouth Amazed 4:00 Lonely Grill LoneStar At Last 3:00 At Last Etta James Baby Got Back 4:21 Millennium Hip-Hop Party Sir Mix-A-Lot Billie Jean 4:54 Thriller Michael Jackson Bless The Broken Road 3:50 Feels Like Today Rascal Flatts Blister in the Sun 2:24 Add It Up (1981-1993) Violent Femmes Boot Scootin' Boogie 3:18 Brooks and Dunn: The Greatest Hits … Brooks & Dunn Brick House 3:46 20th Century Masters - The Millenni… The Commodores Brown Eyed Girl 3:03 Van Morrison Bust A Move 4:24 Millennium Hip-Hop Party Young MC Celebration 3:43 Kool and the Gang ChaCha Slide (club mix) 7:43 Casper Chicken Dance 2:39 Drew's Famous Party Music The Hit Crew Cinderella 4:25 This Moment Steven Curtis Chapman Come Away With Me 3:18 Come Away With Me Norah Jones Come On Eileen 4:15 20th Century Millennium Collection: … Dexy's Midnight Runners Cotton Eye Joe 2:55 ESPN Presents: Jock Jams, Vol. 3 Rednex Crazy 2:58 St. Elsewhere Gnarls Barkley Crazy in Love 3:56 Dangerously in Love Beyoncé Cupid Shufe 3:51 Cupid Shufe - Single Cupid Don't Cha - Alt 3:52 Pussy Cat Dolls Don't Stop the Music 4:27 Good Girl Gone Bad Rihanna Everybody Have Fun Tonight 4:47 Everybody Wang Chung Tonight - W… Wang Chung Everytime We Touch 3:18 Now 21 Cascada Faithfully 4:27 The Essential Journey [Disc 1] Journey Footloose 3:52 Kenny Loggins -

Bat out of Hell 2100 by Jim Steinman an Extended Treatment

BAT OUT OF HELL 2100 BY JIM STEINMAN AN EXTENDED TREATMENT “BAT OUT OF HELL 2100” TITLE CARDS: THE YEAR 2100 SOMEWHERE IN WHAT USED TO BE THE ISLAND OF MANHATTAN BUT WHICH SOMEHOW CHANGED... into something else... PROLOGUE: (No music at all) FADE IN: INT: A MYSTERIOUS BEDROOM (What seems to have once been a perfect bedroom for a fairy tale princess. Whites and pinks and lavenders, flowing satins and silks. Huge windows, lush layered curtains and drapes. A massive canopied bed. But now there is a pervading sense of gradual decay and encroaching ruin. Shadows loom, dust whirls, and intricate webs insinuate themselves into the patterns of the walls and floor corners. Fabrics are torn. Wood is cracked. Glass is chipped. Things are lost. It doesn’t really seem to be a room where anybody lives-- it has the slightly unreal, frozen quality of a museum exhibit that has recently been left a bit too unattended... After moving through the room we come to a woman standing close to one of the largest open windows -- There are sepulchral clouds over the moon and in the slats of light that filter through it is impossible to see her very clearly. She stands totally still, as she brushes her long golden hair, some of which hangs out over the window ledge. She looks up and out and we do too, taking in the hazy outlines of a strange city skyline -- it seems both somewhat futurist and medieval, though so much is obscured by spirals of thick multi-colored smoke and plumes of what seems to be glittering black and gold ash. -

1 Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 2 the Rolling Stones I Can't Get No Satisfaction 3 Derek and the Dominos Layla 4 Led Zeppelin St

1 Bruce Springsteen Born To Run 2 The Rolling Stones I Can't Get No Satisfaction 3 Derek And The Dominos Layla 4 Led Zeppelin Stairway To Heaven 5 The Rolling Stones Sympathy For The Devil 6 Bruce Springsteen Thunder Road 7 Queen Bohemian Rhapsody 8 The Rolling Stones Gimme Shelter 9 The Who Baba O'Riley 10 The Who Won't Get Fooled Again 11 Bob Dylan Like A Rolling Stone 12 Jimi Hendrix Along The Watch Tower 13 The Clash London Calling 14 Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 15 Chuck Berry Johnny B Goode 16 Bruce Springsteen Rosalita 17 Jimi Hendrix Purple Haze 18 Led Zeppelin Whole Lotta Love 19 Led Zeppelin Rock And Roll 20 Lynyrd Skynyrd Free Bird 21 Led Zeppelin Kashmir 22 The Kinks You Really Got Me 23 The Beatles Hey Jude 24 Janis Joplin Piece Of My Heart 25 Bruce Springsteen Jungleland 26 The Beatles Revolution 27 Them Gloria 28 Lou Reed Intro/Sweet Jane 29 The Who My Generation 30 Led Zeppelin Black Dog 31 AC/DC Back In Black 32 The Rolling Stones Cant You Hear Me Knocking 33 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 34 Aerosmith Dream On 35 The Allman Brothers Band Whipping Post 36 The Rolling Stones Paint It Black 37 The Doors Light My Fire 38 Cream Sunshine Of Your Love 39 The Eagles Hotel California 40 The White Stripes Seven Nation Army 41 The Ramones I Wanna Be Sedated 42 The Beatles Helter Skelter 43 The Beatles A Day In The Life 44 The Rolling Stones Monkey Man 45 Elvis Presley Jailhouse Rock 46 Steppenwolf Born To Be Wild 47 Guns N Roses Welcome To The Jungle 48 Tom Petty And The Heart BreakersAmerican Girl 49 Pink Floyd Comfortably Numb 50 The Rolling Stones Jumpin' Jack Flash 51 Pink Floyd Wish You Were Here 52 The Band The Weight 53 Bruce Springsteen Born In The U.S.A. -

AXS TV Canada Schedule for Mon. April 8, 2019 to Sun. April 14, 2019

AXS TV Canada Schedule for Mon. April 8, 2019 to Sun. April 14, 2019 Monday April 8, 2019 3:00 PM ET / 12:00 PM PT 6:00 AM ET / 3:00 AM PT The Big Interview Smart Travels Europe Phil Collins - Legendary singer-songwriter Phil Collins sits down with Dan Rather to talk about Stockholm and Sweden - We cruise through Stockholm’s sun-dappled archipelago, stroll through his anticipated return to the music scene, his record breaking success and a possible future the Karl Milles sculpture garden, and admire the world’s best-preserved 17th century warship, partnership with Adele. the Vasa. Then it’s off to the woodsy “Kingdom of Crystal” and the vacation island of Öland, an out-of-the-way charmer with timeless windmills, ancient ruins and glorious sand beaches. 4:00 PM ET / 1:00 PM PT Rock Legends 6:30 AM ET / 3:30 AM PT Pink Floyd - Pink Floyd, one of the most influential progressive rock bands, released The Dark Rock Legends Side of the Moon in 1973, which became their most critically and commercially successful album. The Monkees - Formed in Los Angeles in 1965 for the American television series The Monkees, the musical acting quartet was composed of Americans Micky Dolenz, Michael Nesmith and 4:30 PM ET / 1:30 PM PT Peter Tork and British actor and singer Davy Jones. Leading music critics cast fresh light on the Bachman & Turner career of The Monkees. After more than 20 years of fan demand, Randy Bachman and Fred Turner - two giants of rock ‘n’ roll - have finally reunited. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

Classic Rock

CLASSIC ROCK ✔ ✔ Alone With You The Sunnyboys Hells Bells AC/DC Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again Angles Here I Go Again Whitesnake American Pie Don McLean Highway To Hell AC/DC Back In Black AC/DC Hit Me With Your Best Shot Pat Benatar Bad To The Bone George Thorogood Hold The Line Toto Ballroom Blitz Sweet Hooked On A Feeling Blue Swede Bat Out Of Hell Meat Loaf Horror Movie Skyhooks Before Too Long Paul Kelly & The Coloured Girls Hot Blooded Foreigner Better The Screaming Jets House Of The Rising Sun The Animals Better Man Pearl Jam Hush Kula Shaker Black Betty Ram Jam (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction The Rolling Stones Black Dog Led Zeppelin I Got The Music In Me Kiki Dee Black Night (Original Single Version) Deep Purple I Got You Split Enz Bohemian Rhapsody Queen I Got You (I Feel Good) James Brown Born In The U.S.A. Bruce Springsteen I Love Rock N' Roll Joan Jett Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison I Wanna Rock and Roll All Night Kiss Build Me Up Buttercup The Foundations I Want to Break Free Queen Can't Buy Me Love The Beatles I Was Made For Lovin' You Kiss Can't Help Myself Icehouse Jessie's Girl Rick Springfield Centerfold J. Geils Band Just Like Fire Would The Saints Chained To The Wheel The Black Sorrows Khe Sanh Cold Chisel Cheap Wine Cold Chisel Knockin' On Heaven's Door Bob Dylan China Grove The Doobie Brothers Kung Fu Fighting Carl Douglas Come Back Again Daddy Cool La Bamba Los Lobos Come On Eileen Dexys Midnight Runners Lay Down Your Guns Jimmy Barnes Copperhead Road Steve Earle Lay Your Love On Me Racey Crazy Little Thing Called -

Ulkomaiset Esittäjät

Ulkomaiset esittäjät Artisti Kappale *NSYNC Bye Bye Bye 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 2 Pac Featuring Dr. Dre California Love 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Changes 2Pac Dear Mama 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 4 Non Blondes What's Up 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Feat. Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5ive We Will Rock You A Great Big World & Christina Aguilera Say Something A Great Big World Feat. Christina Say Something Aguilera A Little Night Music (Broadway Send In The Clowns Version) A1 Like A Rose A1 Take On Me Aashiqui 2 Tum Hi Ho ABBA Angels Eyes Abba Chiquitita Abba Dancing Queen ABBA Does Your Mother Know ABBA Fernando ABBA Gimme Gimme Gimme ABBA Happy New Year ABBA Hasta Manana ABBA Honey Honey ABBA I Do I Do I Do I Do I Do Artisti Kappale ABBA I Have A Dream ABBA Knowing Me Knowing You Abba Knowing Me, Knowing You ABBA Lay All Your Love On Me ABBA Mamma Mia ABBA Money Money Money ABBA One Of Us ABBA Ring Ring ABBA S.O.S ABBA S.O.S. ABBA Summer Night City ABBA Super Trouper ABBA Take A Chance On Me ABBA Thank You For The Music ABBA The Day Before You Came Abba The Name Of The Game Abba The Winner Takes It All Abba Waterloo ABBA Voulez-Vous ABC The Look Of Love AC DC Back In Black AC DC Highway To Hell AC DC Thunderstruck AC/DC Back In Black AC/DC Big Balls AC/DC Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap AC/DC For Those About -

A Beat for You Pseudo Echo a Day in the Life the Beatles a Girl Like

A Beat For You Pseudo Echo A Day In The Life The Beatles A Girl Like You Edwyn Collins A Good Heart Feargal Sharkey A Groovy Kind Of Love Phil Collins A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall Bryan Ferry A Kind Of Magic Queen A Little Less Conversation Elvis vs JXL A Little Ray of Sunshine Axiom A Matter of Trust Billy Joel A Sky Full Of Stars Coldplay A Thousand Miles Vanessa Carlton A Touch Of Paradise John Farnham A Town Called Malice The Jam A View To A Kill Duran Duran A Whiter Shade Of Pale Procol Harum Abacab Genesis About A Girl Nirvana Abracadabra Steve Miller Band Absolute Beginners David Bowie Absolutely Fabulous Pet Shop Boys Accidentally In Love Counting Crows Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus Adam's Song Blink 182 Addicted To Love Robert Palmer Adventure of a Lifetime Coldplay Aeroplane Red Hot Chili Peppers Affirmation Savage Garden Africa Toto After Midnight Eric Clapton Afterglow INXS Agadoo Black Lace Against All Odds (Take A Look At Me Now) Phil Collins Against The Wind Bob Seger Age of Reason John Farnham Ahead of Myself Jamie Lawson Ain't No Doubt Jimmy Nail Ain't No Mountain High Enough Jimmy Barnes Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine The Rockmelons feat. Deni Hines Alive Pearl Jam Alive And Kicking Simple Minds All About Soul Billy Joel All Along The Watchtower Jimi Hendrix All By Myself Eric Carmen All Fired Up Pat Benatar All For Love Bryan Adams, Rod Stewart & Sting All I Do Daryl Braithwaite All I Need Is A Miracle Mike & The Mechanics All I Wanna Do Sheryl Crow All I Wanna Do Is Make Love To You Heart All I Want