Todd Rundgren Reached a Crossroads on November 10, 1973, When His Ballad “Hello It’S Me” Rose to Number 5 on the Billboard Singles Chart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

074-183X XTC/C XTC/2 Operating Manual

OPERATING MANUAL XTC/C XTC/2 XTC/C XTC/2 Thin Film Deposition Controller IPN 074-183 OPERATING MANUAL XTC/C XTC/2 Thin Film Deposition Controller IPN 074-183X TWO TECHNOLOGY PLACE ALTE LANDSTRASSE 6 BONNER STRASSE 498 EAST SYRACUSE, NY 13057-9714 USA LI-9496 BALZERS, LIECHTENSTEIN D-50968 COLOGNE, GERMANY Phone: +315.434.1100 Phone: +423.388.3111 Phone: +49.221.347.40 Fax: +315.437.3803 Fax: +423.388.3700 Fax: +49.221.347.41429 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] VISIT US ON THE WEB AT www.inficon.com ©2001 INFICON 092304 Trademarks The trademarks of the products mentioned in this manual are held by the companies that produce them. INFICON®, CrystalSix® are trademarks of INFICON Inc. All other brand and product names are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective companies. The information contained in this manual is believed to be accurate and reliable. However, INFICON assumes no responsibility for its use and shall not be liable for any special, incidental, or consequential damages related to the use of this product. ©2001 All rights reserved. Reproduction or adaptation of any part of this document without permission is unlawful. DECLARATION OF CONFORMITY This is to certify that this equipment, designed and manufactured by: INFICON Inc. 2 Technology Place East Syracuse, NY 13057 USA meets the essential safety requirements of the European Union and is placed on the market accordingly. It has been constructed in accordance with good engineering practice in safety matters in force in the Community and does not endanger the safety of persons, domestic animals or property when properly installed and maintained and used in applications for which it was made. -

Todd Rundgren to Perform at Four Winds Casinos on June 7

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE TODD RUNDGREN TO PERFORM AT SILVER CREEK EVENT CENTER, FOUR WINDS NEW BUFFALO, ON FRIDAY, JUNE 7 CORRECTED TICKET SALE DATE: Tickets go on sale Friday, March 29 at 10 a.m. ET NEW BUFFALO, Mich. – March 26, 2019 – The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians’ Four Winds® Casinos are pleased to announce Todd Rundgren will perform at Silver Creek® Event Center on Friday, June 7, 2019 at 9 p.m. ET. Ticket prices for the show start at $29 plus applicable fees and can be purchased beginning Friday, March 29 at 10 a.m. ET by visiting FourWindsCasino.com, or by calling (800) 745-3000. Hotel rooms are available on the night of the Todd Rundgren performance and can be purchased with event tickets. As a songwriter, video pioneer, producer, recording artist, computer software developer, conceptualist, and interactive artist (re-designated TR-i), Rundgren has made a lasting impact on both the form and content of popular music. Born and raised in Philadelphia, Rundgren began playing guitar as a teenager, founded the band The Nazz, before launching a solo career. 1972's Something/Anything? prompted the press to dub him 'Rock's New Wunderkind'. It was followed by several albums and hit singles, among them I Saw The Light, Hello It's Me, Can We Still Be Friends, and Bang The Drum. As a producer, Rundgren has worked with Patti Smith, Cheap Trick, Psychedelic Furs, Meatloaf, XTC, Grand Funk Railroad, and Hall And Oates. He composed all the music and lyrics for Joe Papp's 1989 Off-Broadway production of Joe Orton's Up Against It and composed the music for a number of television series, including Pee Wee’s Playhouse and Crime Story. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

EAGLE EYE Written by John Glenn & Travis Wright

EAGLE EYE Written by John Glenn & Travis Wright March 28, 2007 FADE IN: EXT. DESERT DUNES - DAWN CLOSE ON A WOODEN STICK-FIGURE TOY, held by a SIX YEAR OLD BOY. Another BOY grabs the toy away and RUNS OFF, laughing -- CHILDREN are playing under a cluster of date palms, part of a small desert commune somewhere in the Middle East. Their MOTHERS, veiled in black, gather and talk. Bearded, turbaned MEN carrying AK-47's argue politics. A domestic, even tranquil scene of life in another part of the world... EXT. DESERT ROAD - CONTINUOUS A CARAVAN of VEHICLES RACE DOWN A HIGHWAY:. SUV's mounted with surface-to-air RPG's form a protective cordon around a BLACK MERCEDES. As the cars ROAR INTO LENS, we go.to: EXT. RIDGE ABOVE ROAD - DAWN POV THOUGH A LONG-RANGE SCOPE: the caravan as seen by a TWO- MAN SPECIAL OPS TEAM perched on a ridge. As the LEADER surveils the cars, his partner finishes assembling a two-foot UAV (Unmanned Aerial Vehicle), rigging it with EXPLOSIVES: SPECIAL FORCES LEADER We have visual onthetarget. Confirm 'go' for UAV launch. INT. PENTAGON - JOINT OPERATIONS CENTER - NIGHT SUPER: "JOINT OPERATIONS CENTER, THE PENTAGON" Sat-feeds monitor the caravan. Military brass observes: SECRETARY OF DEFENSE GEOFF CALLISTER (50's, African American; eyes with soul and a wary intelligence). Beside him: COLONEL THOMPSON (Full-Bird, decorated). COLONEL THOMPSON Alpha One, you're confirmed 'go': active UAV at GPS papa, zulu, three, zero. EXT. RIDGE ABOVE ROAD - DAWN The Ops Team activates a remote transmitter, LAUNCHING the UAV into the sky like a small ROCKET -- amazingly, its silent. -

FAHRENHEIT 451 by Ray Bradbury This One, with Gratitude, Is for DON CONGDON

FAHRENHEIT 451 by Ray Bradbury This one, with gratitude, is for DON CONGDON. FAHRENHEIT 451: The temperature at which book-paper catches fire and burns PART I: THE HEARTH AND THE SALAMANDER IT WAS A PLEASURE TO BURN. IT was a special pleasure to see things eaten, to see things blackened and changed. With the brass nozzle in his fists, with this great python spitting its venomous kerosene upon the world, the blood pounded in his head, and his hands were the hands of some amazing conductor playing all the symphonies of blazing and burning to bring down the tatters and charcoal ruins of history. With his symbolic helmet numbered 451 on his stolid head, and his eyes all orange flame with the thought of what came next, he flicked the igniter and the house jumped up in a gorging fire that burned the evening sky red and yellow and black. He strode in a swarm of fireflies. He wanted above all, like the old joke, to shove a marshmallow on a stick in the furnace, while the flapping pigeon- winged books died on the porch and lawn of the house. While the books went up in sparkling whirls and blew away on a wind turned dark with burning. Montag grinned the fierce grin of all men singed and driven back by flame. He knew that when he returned to the firehouse, he might wink at himself, a minstrel man, Does% burntcorked, in the mirror. Later, going to sleep, he would feel the fiery smile still gripped by his Montag% face muscles, in the dark. -

Todd Rundgren No World Order Mp3, Flac, Wma

Todd Rundgren No World Order mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Pop Album: No World Order Country: US Released: 1993 Style: Art Rock, Pop Rock, Prog Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1237 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1723 mb WMA version RAR size: 1149 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 799 Other Formats: TTA VOC WAV VOX MP1 VQF MMF Tracklist 1 Worldwide Epiphany 1.0 1:20 2 No World Order 1.0 0:58 3 Worldwide Epiphany 1,1 1:21 4 Day Job 1.0 4:25 5 Property 1.0 4:31 6 Fascist Christ 1.0 5:35 7 Love Thing 1.0 3:44 8 Time Stood Still 1.0 1:42 9 Proactivity 1.0 2:55 10 No World Order 1.1 6:21 11 Worldwide Epiphany 1.2 4:24 12 Time Stood Still 1.1 0:38 13 Love Thing 1.1 1:36 14 Time Stood Still 1.2 2:34 15 Word Made Flesh 1.0 4:37 16 Fever Broke 6:31 Companies, etc. Record Company – BMG Direct Marketing, Inc. – D174489 Credits Performer, Producer, Written-By – Todd Rundgren Photography By – O'Connor*, Lannen* Notes Includes leporello booklet with 16 cover variants for "No World Order". 1993 Alchemedia Productions Inc. Manufactured& Distributed By Forward, A Label of Rhino Records Inc., 10635 Santa Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90025-4900 Manufactured for BMG Direct Marketing, Inc. under License 6550 East 30th Street, Indianapolis, Indiana 46219 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Todd Todd Rundgren / TR-I - R2 71266 Rundgren / No World Order (CD, Forward R2 71266 US 1993 TR-I Album) Todd Todd Rundgren / TR-I - Waking R2 71744 Rundgren / No World Order Lite Dreams Music, R2 71744 US 1994 TR-I (CD, Album) Forward Todd -

Lightning in a Bottle

LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE A Sony Pictures Classics Release 106 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS STEVE BEEMAN LEE GINSBERG CARMELO PIRRONE 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, ANGELA GRESHAM SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 550 MADISON AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 8TH FLOOR PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 NEW YORK, NY 10022 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com 1 Volkswagen of America presents A Vulcan Production in Association with Cappa Productions & Jigsaw Productions Director of Photography – Lisa Rinzler Edited by – Bob Eisenhardt and Keith Salmon Musical Director – Steve Jordan Co-Producer - Richard Hutton Executive Producer - Martin Scorsese Executive Producers - Paul G. Allen and Jody Patton Producer- Jack Gulick Producer - Margaret Bodde Produced by Alex Gibney Directed by Antoine Fuqua Old or new, mainstream or underground, music is in our veins. Always has been, always will be. Whether it was a VW Bug on its way to Woodstock or a VW Bus road-tripping to one of the very first blues festivals. So here's to that spirit of nostalgia, and the soul of the blues. We're proud to sponsor of LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE. Stay tuned. Drivers Wanted. A Presentation of Vulcan Productions The Blues Music Foundation Dolby Digital Columbia Records Legacy Recordings Soundtrack album available on Columbia Records/Legacy Recordings/Sony Music Soundtrax Copyright © 2004 Blues Music Foundation, All Rights Reserved. -

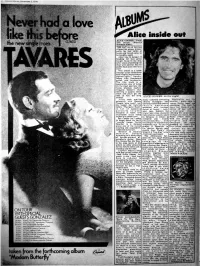

Record-Mirror-1978-1

Record Mora, December 2. 1978 Alice inside out rr ALICE COOPER: 'From The Inside' (Warner Brothers K5677) t , t- THE BAT out of hell has clipped his wings, thrown sz away his last bottle of 1 booze and vowed never to be nAughty again. s Alice was In danger of A heading for that great boogie house In the sky, after years of pickling his Si liver with alcohol. But he pulled back and went on a cure. This album Is a loose a. concept of his reflections . and hospital experiences. t Apocalyptic tracks, , -k heavy with thunderous , II guitar and keyboards. The title track is a panoramic view of being on the road and how the booze troubles started. Imagine 'School's Out' meeting a quality disco track and you'll get the 'idea of how the song on the wagon sounds. ALICE COOPER: Alice now works many assorted seventies Highlights are the primarily with Bernie albums Rundgren has cocktail - piano intro to Taupin, who hasn't lost cleverly fused mid -sixties 'never Never Land' and his talent for incisive idyllic American emotional 'The Verb To lyrics. 'The Quiet Room' melodies with various Love' but 'Hello It's Me' Is full of opposing forms of heavy - rock. comes off best with Its parallels between soul; jazz, Eastern In- archetypal chorus thoughts of home and trigue and even modern utilising the vocal talents frustration about being Instrumental pieces akin of Hall and Oates, Stevie n M locked in a padded cell. to Debussy to create a Nicks (when she's not But Cooper isn't going complete 'pop - sound with her group she's to forget about his early encyclopaedia', and alright) and Rick "weirdo" Image. -

Piano • Vocal • Guitar • Folk Instruments • Electronic Keyboard • Instrumental • Drum ADDENDUM Table of Contents

MUsic Piano • Vocal • Guitar • Folk Instruments • Electronic Keyboard • Instrumental • Drum ADDENDUM table of contents Sheet Music ....................................................................................................... 3 Jazz Instruction ....................................................................................... 48 Fake Books........................................................................................................ 4 A New Tune a Day Series ......................................................................... 48 Personality Folios .............................................................................................. 5 Orchestra Musician’s CD-ROM Library .................................................... 50 Songwriter Collections ..................................................................................... 16 Music Minus One .................................................................................... 50 Mixed Folios .................................................................................................... 17 Strings..................................................................................................... 52 Best Ever Series ...................................................................................... 22 Violin Play-Along ..................................................................................... 52 Big Books of Music ................................................................................. 22 Woodwinds ............................................................................................ -

Inside Holy Cross - Inside

Inside Holy Cross - inside VOL. XXI, NO. 86 FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 6,1987 the independent student newspaper serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s Three platforms to run for SMC student body offices By MARILYN BENCHIK stated, “No experience necessary,” Assistant Saint Mary’s Editor and said, “ So, we’re just going to go for it.” Canidates for Saint Mary’s student Class officer canidates also attended body offices attended the second pre the Thursday night meeting. Running election information meeting Thursday for senior class officer positions are: night. Julie Bennett, Ana Cote, Patti Petro, Election hopefuls were required to at and Lorie Potenti. Potenti said they are tend only one of the two sessions. The not yet sure who will run for which po first pre-election meeting was held sition. Wednesday night. Sandy Cerimele, “ All four of us have had experience election commissioner, and Jeanne Hel in working with student government in ler, student body president, set the the last three years, and we feel we guidelines for campaigning have a great senior class. We want to procedures. make next year the most memorable,” The three platforms, each consisting Petro said. P of three canidates for the offices of Cote added, “Our experience is one president, vice president for student af of the most im portant factors to be con fairs, and vice president for academic sidered. We’ve already learned to deal affairs, are: Ann Rucker, Ann Reilly, with students’ problems and the issues and Ann Eckhoff; Sarah Cook, Janel which may arise.” Hamann, and Jill Hinterhalter; Eileen Canidates for the junior class posi Hetterich, Smith Hashagen, and Julie tions of president, vice president, sec Parrish. -

SOME KIND of WAY out by BARBARA GORMAN A

SOME KIND OF WAY OUT by BARBARA GORMAN A thesis submitted to the Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts Graduate Program in Creative Writing written under the direction of Prof. Lauren Grodstein and approved by ______________________________ Prof. Lauren Grodstein Camden, New Jersey October 2013 i THESIS ABSTRACT SOME KIND OF WAY OUT By BARBARA GORMAN Thesis Director: Prof. Lauren Grodstein Sixteen-year-old classic rock and blues guitar aficionado Drew Gilmore and his fourteen- year-old sister Cori have been helping their divorced mother Michelle cope with her advanced multiple sclerosis for the past two years to the best of their ability, but the severe sensory pain and uncontrollable muscle spasms have left Michelle, a former grocery store cashier, confined to a wheelchair most days and unable to sleep most nights. A concerned social worker and a few school staff members have begun to question whether Drew and Cori’s needs are being met at home. Drew is resistant and at times hostile toward any suggestions that Michelle may be unable to take care of them, insisting that he and Cori have plenty of help from family and friends in their working class neighborhood of Gloucester City, New Jersey, and that their father Frank, a prison guard who lives in Trenton, New Jersey, with his new wife and toddler son, does the grocery shopping and takes care of the bills. But Drew knows that things at home are far from okay, forcing things at school to a breaking point. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P.