Drovers,Cattleand Dung: the Long Trail from Scotlandto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bury St Edmunds

THE BURY ST EDMUNDS IP31 2PJ TBS YARD - GREATBARTON MOT Prep Exhausts Servicing Brakes Battries Tyres - Repars Open 7 Days a Week Issue 41 November 2020 Delivered from 26/10/20 Monday - Friday 8am - 17.30 Saturday 8am - 4pm Also covering - Horringer Westley - The Fornhams - Great Barton Sundays by Appointmnet only AAdvertisingdvertising SSales:ales: 0012841284 559292 449191 wwww.flww.fl yyeronline.co.ukeronline.co.uk The Flyer #YourFuture #YourSay - West Suffolk Local Plan at open all hours exhibition A virtual exhibition at a village hall space, or over the phone on 01284 that is open all hours is part of new 757368. initiatives designed to put residents at the heart of forming a new Local Plan The Local Plan helps local communities for West Suffolk. continue to thrive in the future by setting out where homes will be built A new 10 week consultation has and supports, with other Council been launched this week on the policies) where new jobs and other Local Plan which will help shape the vital facilities are located. All West future of communities and supporting Suffolk planning decisions are judged development up to 2040. against Local Plan policies. and Options which will started on 13 and seeking comments on a variety October and will last for 10 weeks. of issues and options. This includes West Suffolk Council are now asking The Local Plan ensures the right questions such as have we identifi ed people to have their say on the initial number and types of homes are built This initial stage which will help shape the challenges correctly, and relevant Issues and Options phase which sets in the right places and through its the plan and the future of West Suffolk local issues, as well whether we have the foundations of the formation of policies supports the provision of as it develops. -

Classes and Activities in the Mid Suffolk Area

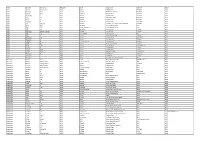

Classes and activities in the Mid Suffolk area Specific Activities for Cardiac Clients Cardiac Exercise 4 - 6 Professional cardiac and exercise support set up by ex-cardiac patients. Mixture of aerobics, chair exercises and circuits. Education and social. Families and carers welcome. Mid Suffolk Leisure Centre, Stowmarket, IP14 1LH on Monday 2-3pm, Wednesday 2.30pm-3.30pm and Friday 10.45 – 11.45am. Bob Halls 01449 674980 or 07754 522233 Red House (Old Library), Stowmarket, IP14 1BE on Friday 1.30-2.30pm. Maureen Cooling 01787 211822 3 27/02/2017 General Activities Suitable for all Clients Aqua Fit 4-6 A fun and invigorating all over body workout in the water designed to effectively burn calories with minimal impact on the body. Great for those who are new or returning to exercise. Mid Suffolk Leisure Centre, Stowmarket, IP14 1LH on Monday 2-3pm (50+), Tuesday 1-2pm and Thursday 9.10 - 9.55pm. Becky Cruickshank 01449 674980 Stradbroke Leisure Centre, IP21 5JN on Monday 12pm-12.45pm, Tuesday 1.45- 2.30pm, Thursday 11- 11.45 and 6.30-7.30pm. Stuart Murdy 01379384376. Balance Class 3 Help with posture and stability. Red Gables Community Centre, Stowmarket, IP14 1BE on Mondays (1st, 2nd and 4th) at 10.15-11am. Lindsay Bennett 01473 345350 Body Balance 4-6 BODYBALANCE™ is the Yoga, Tai Chi, Pilates workout that builds flexibility and strength and leaves you feeling centred and calm. Controlled breathing, concentration and a carefully structured series of stretches, moves and poses to music create a holistic workout that brings the body into a state of harmony and balance. -

Suffolk. · [1\Elly's Waxed Paper Manufctrs

1420 WAX SUFFOLK. · [1\ELLY'S WAXED PAPER MANUFCTRS. Cowell J. Herringswell, Mildenhall S.O HoggerJn.ThorpeMorieux,BildestonS.O Erhardt H. & Co, 9 & 10 Bond court, Cowle Ernest, Clare R.S.O Hogger William, Bildeston S.O London E c; telegraphic address, CracknellJ.MonkSoham, Wickhm.Markt Hollmgsworth Saml. Bred field, Woodbdg "Erhardt, London" Cracknell Mrs. Lucy, Redlingfield, Eye IIowardW.Denningtn.Framlnghm.R.S.O Craske S. Rattlesden, BurySt.Edmunds Howes HaiTy, Debenham, Stonham WEIGHING MACHINE MAS. Crick A. Wickhambrook, Newmarket Hubbard Wm.llessett,BurySt.Edmunds Arm on Geo. S. 34 St.John's rd. Lowestoft Crisp Jn. RushmereSt. Andrew's, Ipswich J effriesE.Sth.ElmhamSt.George,Harlstn Cross J.6 OutN0rthgate,BurySt.Edmds Jillings Thos. Carlton Colville, Lowestft Poupard Thomas James 134 Tooley Cross Uriah, Great Cornard, Sudbury Josselyn Thomas, Belstead, Ipswich street London 8 E ' Crouchen George, Mutford, Beccles J osselyn Thomas, Wherstead, Ipswich ' Crow Edward, Somerleyton, Lowestoft Keeble Geo.jun.Easton, WickhamMarket WELL SINKERS. Cullingford Frederick, Little street, Keeble Samuel William, Nacton, Ipswich Alien Frederick Jas. Station rd. Beccles Yoxford, Saxmundham · Kendall Alfred, Tuddenham St. Mary, Chilvers William John Caxton road Culpitt John, Melton, Woodbridge Mildenhall S.O Beccles & at Wangford R.S.O ' Cur~is 0. Geo.Bedfiel~, ',"ickha~Market Kent E. Kettleburgh, Wickham Market Cornish Charles Botesdale Diss Damels Charles,Burkttt slane, ~udbury Kent John, Hoxne, Scole Prewer Jn. Hor~ingsheath; Bury St. Ed Davey Da:vi_d, Peasenhall, Saxrnund~am Kerry J~~Il:• Wattisfield, Diss Youell William Caxton road Beccles Davey "\Vllham, Swan lane, Haverh1ll Kerry\\ 1lham, Thelnetham, Thetford ' ' Davy John, Stoven, Wangford R.S.O Kerry William, Wattisfield, Diss WHABFINGERS. -

Parish Mag Master

PARISH MAGAZINE Redgrave cum Botesdale and Rickinghall Village Word Search July 2012 Find the following words in the grid above Botesdale Bridewell Church Ducks Farmers Market Fen Hairdressers Hall Inferior Kitchen Manor Mid Suffolk Mobile Library Newsagents Parish Park Farm Pond Post Office Pub Redgrave Rickinghall St Botolphs Way Stream Street Superior Takeaway Tinteniac Ulfketel Village Waveney Rev’d Chris Norburn Rector of Redgrave cum Botesdale with the Rickinghalls The Rectory, Bury Road, Rickinghall, Diss. IP22 1HA Tel: 01379 898685 St Mary’s Rickinghall Inferior now has a web site http://stmarysrickinghallinferior.onesuffolk.net/ or Google: St Mary's Rickinghall Inferior When my passions rise up inside me I often find myself compelled we often call the ‘gospels’, the to speak. For me this happens when an issue close to my heart is narratives of Jesus’ life and death, being discussed by others and I feel compelled to interject. For me were only written later for the this also happens when I feel an injustice is being, or about to be benefit of those who had already perpetrated. Compulsion to speak out can be for many different accepted the gospel! They were in reasons and can sometimes take you by surprise, so there are many no sense the basis of Christianity different patterns to our compulsions to speak out. Likewise there because they were first written for are no fixed patterns for God as he speaks to us and compels us to those who had already converted to speak for him here. Christianity. The first fact in the Rev history of Christianity is that a This means that there are many different ways of bringing people number of people (Jesus’ disciples and first followers) say that they into His Kingdom. -

Babergh District Council Work Completed Since April

WORK COMPLETED SINCE APRIL 2015 BABERGH DISTRICT COUNCIL Exchange Area Locality Served Total Postcodes Fibre Origin Suffolk Electoral SCC Councillor MP Premises Served Division Bildeston Chelsworth Rd Area, Bildeston 336 IP7 7 Ipswich Cosford Jenny Antill James Cartlidge Boxford Serving "Exchange Only Lines" 185 CO10 5 Sudbury Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Bures Church Area, Bures 349 CO8 5 Sudbury Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Clare Stoke Road Area 202 CO10 8 Haverhill Clare Mary Evans James Cartlidge Glemsford Cavendish 300 CO10 8 Sudbury Clare Mary Evans James Cartlidge Hadleigh Serving "Exchange Only Lines" 255 IP7 5 Ipswich Hadleigh Brian Riley James Cartlidge Hadleigh Brett Mill Area, Hadleigh 195 IP7 5 Ipswich Samford Gordon Jones James Cartlidge Hartest Lawshall 291 IP29 4 Bury St Edmunds Melford Richard Kemp James Cartlidge Hartest Hartest 148 IP29 4 Bury St Edmunds Melford Richard Kemp James Cartlidge Hintlesham Serving "Exchange Only Lines" 136 IP8 3 Ipswich Belstead Brook David Busby James Cartlidge Nayland High Road Area, Nayland 228 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Nayland Maple Way Area, Nayland 151 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Nayland Church St Area, Nayland Road 408 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Nayland Bear St Area, Nayland 201 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Nayland Serving "Exchange Only Lines" 271 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Shotley Shotley Gate 201 IP9 1 Ipswich -

Botesdale / Rickinghall 2011

conservation area appraisal © Crown copyright All rights reserved Mid Suffolk D C Licence no 100017810 2009 Introduction The villages of Rickinghall Inferior, Rickinghall Superior and Botesdale were designated as a conservation area in 1973 jointly by East and West Suffolk County Councils and inherited by Mid Suffolk District Council at its inception in 1974. The Council has a duty to review its conservation area designations from time to time, and this appraisal examines Rickinghall and Botesdale under a number of different headings as set out in English Heritage’s new ‘Guidance on Conservation Area Appraisals’ (2006). As such it is a straightforward appraisal of Rickinghall and Botesdale’s built environment in conservation terms. This document is neither prescriptive nor overly descriptive, but more a demonstration of ‘quality of place’, sufficient for the briefing of the Planning Officer when assessing proposed works in the area. The photographs and maps are thus intended to contribute as much as the text itself. As the English Heritage guidelines point out, the appraisal is to be read as a general overview, rather than as a comprehensive listing, and the omission of any particular building, feature or space does not imply that it is of no interest in conservation terms. Text, photographs and map overlays by Patrick Taylor, Conservation Architect, Mid Suffolk District Council 2009. © Crown copyright All rights reserved Mid Suffolk D C Licence no 100017810 2009 Topographical Framework The villages of Rickinghall and Botesdale have become merged into a single settlement along about a mile of former main road six miles south-west of the Norfolk market town of Diss, in the northern part of Mid Suffolk District. -

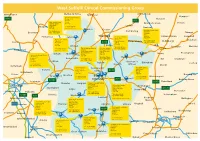

West Suffolk Commiss Map V5

West Suffolk Clinical Commissioning Group Welney Wimblington Methwold Hythe Mundford Attleborough Hempnall Brandon Medical Practice A141 31 High Street Bunwell Brandon A11 Lakenheath Surgery Suffolk 135 High Street IP27 0AQ New Buckenham Shelton Lakenheath Larling Littleport Suffolk Tel: 01842 810388 Fax: 01842 815750 Banham IP27 9EP Brandon Croxton Botesdale Health Centre Tel: 01842 860400 East Harling Back Hills Downham Fax: 01842 862078 Botesdale Alburgh Diss Prickwillow Lakenheath Thetford Dr Hassan & Partners Norfolk Pulham St Mary Redenhall 10 The Chase IP22 1DW Market Cross Surgery Stanton Mendham Ely 7 Market Place Bury St Edmunds Garboldisham Tel: 01379 898295 Dickleburgh Sutton Mildenhall A134 Suffolk Fax: 01379 890477 Suffolk IP31 2XA IP28 7EG Eriswell Euston Diss Tel: 01359 251060 Brockdish Metfield Tel: 01638 713109 The Guildhall and Barrow The Swan Surgery Fax: 01359 252328 Scole Haddenham Fax: 01638 718615 Surgery Northgate Street Lower Baxter Street Bury St Edmunds Bury St Edmunds Suffolk Botesdale Fressingfield Isleham Mildenhall Suffolk IP33 1AE Brome The Rookery Medical Centre IP33 1ET The Rookery Tel: 01284 770440 Stanton Newmarket Barton Mills Tel: 01284 701601 Fax: 01284 723565 Eye Stradbroke Suffolk Fax: 01284 702943 CB8 8NW Wicken Fordham Walsham le Ingham Gislingham Laxfield Tel: 01638 665711 Ixworth Willows Occold Cottenham Fax: 01638 561280 Victoria Surgery Fornham All The Health Centre Burwell Victoria Street Heath Road Bury St Edmunds Saints A143 Woolpit Waterbeach Suffolk SuffolkBacton IP33 3BB IP30 9QU Histon -

SCHOOL ADDRESS HEADTEACHER Phone Number Website Email

SCHOOL LIST BY TOWN SEPTEMBER 2020 ADDRESS HEADTEACHER Phone SCHOOL Website email address number Acton CEVCP School Lambert Drive Acton Sudbury CO10 0US Mrs Julie O'Neill 01787 http://www.acton.suffolk.sch.uk [email protected] 377089 Bardwell CoE Primary School School Lane Bardwell Bury St Edmunds IP31 1AD Mr Rob Francksen 01359 http://www.tilian.org.uk/ [email protected] 250854 Barnham CEVCP School Mill Lane Barnham Thetford IP24 2NG Mrs Amy Arnold 01842 http://www.barnham.suffolk.sch.uk/ [email protected] 890253 Barningham CEVCP School Church Road Barningham Bury St Edmunds IP31 1DD Mrs Frances Parr 01359 http://www.barningham.suffolk.sch.uk/ [email protected] 221297 Barrow CEVCP School Colethorpe Lane Barrow Bury St Edmunds IP29 5AU Mrs Helen Ashe 01284 http://barrowcevcprimaryschool.co.uk/ [email protected] 810223 Bawdsey CEVCP School School Lane Bawdsey Woodbridge IP12 3AR Mrs Katie Butler 01394 http://www.bawdsey.suffolk.sch.uk/ [email protected] 411365 Bedfield CEVCP School Bedfield Woodbridge IP13 7EA Mrs Martine Sills 01728 http://www.bedfieldschool.co.uk/ [email protected] 628306 Benhall: St Mary’s CEVCP School School Lane Benhall Saxmundham IP17 1HE Mrs Katie Jenkins 01728 http://www.benhallschool.co.uk/ [email protected] 602407 Bentley CEVCP School Church Road Bentley Ipswich IP9 2BT Mrs Joanne Austin 01473 http://www.bentleycopdock.co.uk/ [email protected] 310253 Botesdale : St Botolph’s CEVCP Back Hills Botesdale Diss IP22 1DW Mr -

Roll of Honour

Parish Surname First name Honours Rank Major unit Sub unit Notes Acton Aldous Frank James NULL Private Suffolk Regt 5th Batt NULL Acton Bearham W S NULL Private Bedfordshire Regt 9th Batt NULL Acton Byham G W NULL Rifleman Rifle Brigade 3rd Batt NULL Acton Chambers J NULL Private Suffolk Regt 7th Batt NULL Acton Eady W F NULL Private Middlesex Regt 8th Batt NULL Acton Finch G NULL Private Suffolk Regt 9th Batt NULL Acton Goodwin H NULL Drummer Suffolk Regt 11th Batt NULL Acton Hill H B W E NULL Private Queen's Own Royal West Kent Regt 6th Batt NULL Acton Jarvis W G NULL Sergeant Royal Field Artillery NULL NULL Acton King C G NULL Farrier Corporal Army Service Corps NULL NULL Acton King F J NULL Sergeant Suffolk Regt 9th Batt NULL Acton Munnings William George NULL Private Suffolk Regt 9th Batt NULL Acton Nice F C NULL Guardsman Scots Guards NULL NULL Acton Nice P NULL Private Bedfordshire Regt 7th Batt NULL Acton Pleasants H S NULL Private London Regt 18th Batt NULL Acton Pleasants R NULL Private Suffolk Regt 9th Batt NULL Acton Sargent H NULL Lance/Corporal Suffolk Regt 4th Batt NULL Acton Smith A T NULL Private Bedfordshire Regt 7th Batt NULL Acton Smith C M NULL Private London Regt 1st/19th Batt NULL Acton Stearns A NULL Private Suffolk Regt 9th Batt NULL Acton Stearns M W NULL Private Suffolk Regt 9th Batt NULL Acton Tyrrell NULL NULL Private Middlesex Regt 1st/7th Batt NULL Acton Woodgate H NULL Private Suffolk Regt 2nd Batt NULL Acton Woodgate J NULL Private Suffolk Regt 9th Batt NULL Acton Woodgate T NULL Private Loyal North Lancashire -

The London Gazette, September 2, 1870

4062 THE LONDON GAZETTE, SEPTEMBER 2, 1870. trustee at the Crown Bank, Norwich, on and after the said In the Matter of David Humphreys, Jnnr., Grocer, &c., 14th day of Septembtr, 1870, between the hours of eleven Welsbpool. Petition dated 12th October, 1869. o'clock in the forenoon and four o'clock in thea fternoin. HEREBY give notice, that the creditors who have No Dividend can be paid nnless the securities held by the I proved their debts under the above estate, may creditor are produced.—Crown Bank, Norwich, Isl Sep- receive a First Dividend of 8d. in the pound, upon tember, 1870. application at my office, Central Chambers, No. I7<v I. B. COAKS, Solicitor in the Bankruptcy. South Castle-street, Liverpool, on Wednesday, the 7th day of September, 1870, or any subsequent Wednesday, between Harvey's and Hudson's Bankruptcy. the hours of twelve and two o'clock. No Dividend will be In the County Court of Norfolk, holden at Norwich. paid without the production of the securities exhibited at In the Matter of Roger Allday Kerrison. of the city of the time of proving the debt. Executors and administrators Norwich, and of Cromer, Diss, East Dereham, East will be required to produce the probate of the will, or the Hading, Harleston, Hinjham, Loddon, Reepham, Swaff- letters of administration under which they claim. ham, Watton, North Walsham, and Wymondbani, in CHARLES TURNER, Official Assignee. the county of Norfolk, and of Aldborough. Bury, Botesdale, Bungay, Eye, Framlingham, Haleswortb, In the Matter of Thomas Slater, Baker and Flour Dealen Lowestuft, Saxmundham, Southwold, Stow market, Everton. -

£385,000 the Old Saddlers Market Place | Botesdale | Diss | Norfolk | IP21 1BT

Market Place Botesdale £385,000 The Old Saddlers Market Place | Botesdale | Diss | Norfolk | IP21 1BT Bury St Edmunds 17 miles, Diss 6 miles A substantial 2,500 sq ft Grade II Listed four bedroomed semi-detached village house with further potential to enlarge (STP). Study/Hall | Bar | Dining Room | Sitting Room | Kitchen/Breakfast Room | Utility Area | Downstairs Bedroom | Bathroom | Cellar | Three First Floor Bedrooms | Family Bathroom | Attached Barn | Off Street Parking | Pretty Rear Gardens The Old Saddlers The Old Saddlers is a delightful timber framed Grade II Listed property believed to date back to the early 1400s. The property presents rendered and partially jetted elevation under a pantile roof and is of timber frame construction. The accommodation extends to just over 2,500ft2. Of particular note is the sitting room with villager wood burner in chimney recess with decorate mantle (believed to have originated from Redgrave Hall). Also of Outside Location note is the fully fitted kitchen/breakfast room with opening The Old Saddlers is approached over a gravel parking area The Old Saddlers is situated within the market place of the through to a utility room. The ground floor also has the for three cars via a pedestrian gate. The rear garden is village of Botesdale. Botesdale with the adjoining village of benefit of a downstairs bedroom and bathroom. The predominately laid to lawn with mature trees and shrubs. Rickinghall offer a range of shopping facilities with primary ground floor also comprises hall/study, bar and dining There is a further area through a bricked arch which schooling, church, local chapel, garage, health centre, room. -

The Betts of Wortham in Suffolk· (B 1480-1905 by Katharine Frances Doughty ~ W ~ W ~ with Xxv Illustrations

THE BETTS OF WORTHAM IN SUFFOLK· (B 1480-1905 BY KATHARINE FRANCES DOUGHTY ~ W ~ W ~ WITH XXV ILLUSTRATIONS LONDON JOHN LANE THE BODLEY HEAD NEW YORK JOHN LANE COMP ANY MCMXII 711nibull c!r' Sp,ars, Prinlws, EdiH!n,rglt THE BETTS OF WORTHAM IN SUFFOLK : : 1480-1905 TO MY FATHER AT WHOSE SUGGESTION THIS BOOK WAS BEGUN AND WITH WHOSE HELP IT HAS BEEN FINISHED ACKNOWLEDGMENTS WISH to express my gratitude to Mr J. H. J eayes of the MSS. Department British Museum, and to Mr V. B. Redstone, Hon. Secretary of the Norfolk I and Suffolk Archac:ological Society, for help in deciphering the most ancient of the Betts' charters. The late Rev. Canon J. J. Raven, D.D., author of" The Church Bells of Suffolk," etc., also gave me most kind and valuable assistance in this respect. Mr Harold Warnes of Eye kindly allowed me to examine the rolls of the manor of Wortham Hall, and other documents under his care. To the Rev. Edmund Farrer, author of "Portraits in Suffolk Houses," I am greatly indebted for expert and friendly help. Mr G. Milner-Gibson Cullum, F.S.A., has kindly allowed me to consult his as yet unpublished Genealogical Notes. The Rev. C. W. Moule, Fellow and Librarian of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, was so good as to assist me with information respecting the" Red Book of Eye." The Rev. Sir William Hyde Parker has favoured me with some interesting suggestions. My thanks for their courtesy in permitting me to consult their parish registers, are due to the Rector of Wortham, the Rev.