2015 Bird Damage Management in Wisconsin EA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rare Birds of California Now Available! Price $54.00 for WFO Members, $59.99 for Nonmembers

Volume 40, Number 3, 2009 The 33rd Report of the California Bird Records Committee: 2007 Records Daniel S. Singer and Scott B. Terrill .........................158 Distribution, Abundance, and Survival of Nesting American Dippers Near Juneau, Alaska Mary F. Willson, Grey W. Pendleton, and Katherine M. Hocker ........................................................191 Changes in the Winter Distribution of the Rough-legged Hawk in North America Edward R. Pandolfino and Kimberly Suedkamp Wells .....................................................210 Nesting Success of California Least Terns at the Guerrero Negro Saltworks, Baja California Sur, Mexico, 2005 Antonio Gutiérrez-Aguilar, Roberto Carmona, and Andrea Cuellar ..................................... 225 NOTES Sandwich Terns on Isla Rasa, Gulf of California, Mexico Enriqueta Velarde and Marisol Tordesillas ...............................230 Curve-billed Thrasher Reproductive Success after a Wet Winter in the Sonoran Desert of Arizona Carroll D. Littlefield ............234 First North American Records of the Rufous-tailed Robin (Luscinia sibilans) Lucas H. DeCicco, Steven C. Heinl, and David W. Sonneborn ........................................................237 Book Reviews Rich Hoyer and Alan Contreras ...........................242 Featured Photo: Juvenal Plumage of the Aztec Thrush Kurt A. Radamaker .................................................................247 Front cover photo by © Bob Lewis of Berkeley, California: Dusky Warbler (Phylloscopus fuscatus), Richmond, Contra Costa County, California, 9 October 2008, discovered by Emilie Strauss. Known in North America including Alaska from over 30 records, the Dusky is the Old World Warbler most frequent in western North America south of Alaska, with 13 records from California and 2 from Baja California. Back cover “Featured Photos” by © Kurt A. Radamaker of Fountain Hills, Arizona: Aztec Thrush (Ridgwayia pinicola), re- cently fledged juvenile, Mesa del Campanero, about 20 km west of Yecora, Sonora, Mexico, 1 September 2007. -

Henslow's Sparrows: an Up-Date by Madeline J.W

59 Henslow's Sparrows: An Up-Date by Madeline J.W. Austen Introduction Knapton 119821 reported that only In Canada, Henslow's Sparrow 17 individuals in seven widely (Ammodramus henslowiil has been scattered areas across southern known to breed in Ontario and in Ontario were detected during the southwestern Quebec. In recent 1981 breeding season. In 1983, the years, Henslow's Sparrow has been known Ontario population of known to breed only in Ontario, with Henslow's Sparrows was 25 to 29 the majority of nesting sites in the individuals at 13 sites (Ontario mid-1980s being located in the Breeding Bird Atlas; Risley 19831. southern part of Hastings, Lennox During the Atlas of the Breeding Addington, and Frontenac Counties, Birds of Ontario, the Henslow's and in Prince Edward County. It also Sparrow was found in only 38 has occurred in Grey, Bruce, and squares, and in only 8% of these was Dufferin Counties. Figure 1 shows breeding confirmed (Cadman et al. the breeding distribution of 19871. At this time, it was unlikely Henslow's Sparrow in Ontario, based that the total provincial population on data from the Breeding Bird Atlas exceeded 50 pairs in any given year and the Ontario Rare Breeding Bird (Knapton 1987). The ORBBP received Program (ORBBPI. information on only 23 Henslow's This article provides an up-date Sparrow sites, seven of which were on the status of Henslow's Sparrow active during the 1986 to 1991 period. and summarizes the results of survey However, breeding site information efforts since Knapton (19861. from the Kingston area was not reported to the ORBBP. -

Early- to Mid-Succession Birds Guild

Supplemental Volume: Species of Conservation Concern SC SWAP 2015 Early- to Mid-Succession Birds Guild Bewick's Wren Thryomanes bewickii Blue Grosbeak Guiraca caerulea Blue-winged Warbler Vermivora pinus Brown Thrasher Toxostoma rufum Chestnut-sided Warbler Dendroica pensylvanic Dickcissel Spiza americana Eastern Kingbird Tyrannus tyrannus Eastern Towhee Pipilo erythrophthalmus Golden-winged Warbler Vermivora chrysoptera Gray Kingbird Tyrannus dominicensis Indigo Bunting Passerina cyanea Orchard Oriole Icterus spurius Prairie Warbler Dendroica discolor White-eyed Vireo Vireo griseus Yellow-billed Cuckoo Coccyzus americanus Yellow-breasted Chat Icteria virens NOTE: The Yellow-billed Cuckoo is also discussed in the Deciduous Forest Interior Birds Guild. Contributors (2005): Elizabeth Ciuzio (KYDNR), Anna Huckabee Smith (NCWRC), and Dennis Forsythe (The Citadel) Reviewed and Edited: (2012) John Kilgo (USFS), Nick Wallover (SCDNR); (2013) Lisa Smith (SCDNR) and Anna Huckabee Smith (SCDNR) DESCRIPTION Taxonomy and Basic Description All bird species in this guild belong to the taxonomic order Passeriformes (perching birds) and they are grouped in 9 different families. The Blue-winged, Chestnut-sided, Golden-winged, and Prairie Warblers are in the family Parulidae (the wood warblers). The Eastern and Gray Kingbirds are in the flycatcher family, Tyrannidae. The Blue Grosbeak, Dickcissel, and Indigo Bunting are in the family Cardinalidae. The Bewick’s Wren is in the wren family, Troglodytidae. The orchard oriole belongs to the family Icteridae. The Brown Thrasher is in the family Mimidae, the Yellow-billed Cuckoo belongs to the family Cuculidae, the Eastern Towhee is in the family Emberizidae, and the White-eyed Vireo is in the family Vireonidae. All are small Blue-winged Warbler birds and can be distinguished by song, appearance, and habitat preference. -

Blue Grosbeak Passerina Caerulea Lush, Low Plants, Growing in Damp Swales, Offer Prime Habitat for the Blue Grosbeak. the Grosbe

Cardinals, Grosbeaks, and Buntings — Family Cardinalidae 549 Blue Grosbeak Passerina caerulea Lush, low plants, growing in damp swales, offer prime habitat for the Blue Grosbeak. The grosbeak is primarily a summer visitor to San Diego County, locally common at the edges of riparian woodland and in riparian scrub like young willows and mule- fat. Blue Grosbeaks can also be common in grassy uplands with scattered shrubs. Migrants are rarely seen away from breeding habitat, and in winter the species is extremely rare. Breeding distribution: The Blue Grosbeak has a distri- bution in San Diego County that is wide but patchy. Areas of concentration correspond to riparian corridors and Photo by Anthony Mercieca stands of grassland; gaps correspond to unbroken chap- arral, forest, waterless desert, and extensive development. breeds up to 4100 feet elevation north of Julian (J20; up Largely insectivorous in summer, the Blue Grosbeak to nine on 1 July 1999, M. B. Stowe) and to 4600 feet at forages primarily among low herbaceous plants, native Lake Cuyamaca (M20; up to five on 10 July 2001, M. B. or exotic. So valley bottoms, where the water necessary Mulrooney). A male near the Palomar Observatory (D15) for the vegetation accumulates, provide the best habitat. 11 June–21 July 1983 (R. Higson, AB 37:1028, 1983) was Grassland is also often good habitat, as can be seen on exceptional—and in an exceptionally wet El Niño year. In Camp Pendleton (the species’ center of abundance in the Anza–Borrego Desert the Blue Grosbeak is confined San Diego County) and from Warner Valley south over as a breeding bird to natural riparian oases. -

Worcester County Birdlist

BIRD LIST OF WORCESTER COUNTY, MASSACUSETTS 1931-2019 This list is a revised version of Robert C. Bradbury’s Bird List of Worcester County, Massachusetts (1992) . It contains bird species recorded in Worcester County since the Forbush Bird Club began publishing The Chickadee in 1931. Included in Appendix A, and indicated in bold face on the Master List are bird Species which have been accepted by the Editorial Committee of The Chickadee, and have occurred 10 times or fewer overall, or have appeared fewer than 5 times in the last 20 years in Worcester County. The Editorial Committee has established the following qualifying criteria for any records to be considered of any record not accepted on the Master List: 1) a recognizable specimen 2) a recognizable photograph or video 3) a sight record corroborated by 3 experienced observers In addition, any Review Species with at least one accepted record must pass review of the Editorial Committee of the Chicka dee. Any problematic records which pass review by the Chickadee Editorial Committee, but not meeting the three first record rules above, will be carried into the accepted records of the given species. Included in Appendix B are records considered problematic. Problematic species either do not meet at least one of the qualifying criteria listed above, are considered likely escaped captive birds, have arrived in Worcester County by other than self-powered means, or are species not yet recognized as a count able species by the Editorial Committee of The Chickadee . Species names in English and Latin follow the American Ornithologists’ Union Checklist of North American Birds, 7 th edition, 59th supplement, rev. -

Monitoring Bobolink Abundance and Breeding in Response to Stewardship Andrew J

Toronto, Ontario Monitoring bobolink abundance and breeding in response to stewardship Andrew J. Campomizzi, Zoé M. Lebrun-Southcott Bird Ecology and Conservation Ontario 10 April 2019 Abstract Stewardship actions are ongoing for the federally- and provincially-threatened bobolink (Dolichonyx oryzivorus) in Ontario because of population declines. Stewardship actions in the province focus on maintaining and enhancing breeding habitat, primarily in agricultural grasslands. Unfortunately, most stewardship practices are not monitored for impacts on bobolink. We conducted low-intensity field surveys (i.e., transect surveys, point counts) and compared data with intensive monitoring (i.e., spot mapping and nest monitoring) to assess if low-intensity surveys could accurately estimate bobolink abundance and detect evidence of breeding. We monitored 36 fields (254 ha) of late-harvest hay, restored grassland, and fallow fields in the Luther Marsh Wildlife Management Area and on 4 farms in southern Ontario, Canada. Distance sampling analysis using transect surveys provided a reasonable estimate of male bobolink abundance (mean = 230, 95% CI = 187 to 282) compared to the 197 territories we identified through spot mapping. Bobolink territories occurred in 78% (n = 36) of fields and all fields with territories had evidence of nesting and fledging, based on spot mapping and nest monitoring. Neither transect surveys nor point counts accurately identified evidence of nesting or fledging in fields compared to spot mapping and nest monitoring. We recommend using transect surveys as an efficient field method and distance sampling analysis to estimate male bobolink abundance in fields managed for the species. If estimates of fledging success are needed, we recommend nest monitoring, although sub-sampling may be necessary because the method is labour intensive. -

Dickcissel Spiza Americana

Wyoming Species Account Dickcissel Spiza americana REGULATORY STATUS USFWS: Migratory Bird USFS R2: No special status USFS R4: No special status Wyoming BLM: No special status State of Wyoming: Protected Bird CONSERVATION RANKS USFWS: Bird of Conservation Concern WGFD: NSSU (U), Tier II WYNDD: G5, S1 Wyoming Contribution: LOW IUCN: Least Concern PIF Continental Concern Score: 10 STATUS AND RANK COMMENTS Dickcissel (Spiza americana) has no additional regulatory status or conservation rank considerations beyond those listed above. NATURAL HISTORY Taxonomy: There are currently no recognized subspecies of Dickcissel 1. Description: Identification of Dickcissel is possible in the field. This species is sexually dimorphic in both size (males average 10–20% larger than females) and plumage 2. Adults weigh 23–29 g, range in length from 14–16 cm, and have a wingspan of approximately 25 cm 2, 3. Adult males have a gray head with yellow eyebrows and malars, rufous shoulders, a distinct V-shaped black throat patch, yellow breast, light-gray belly, dark eyes, and gray bill and legs 2, 3. Males are unlikely to be confused with any other species in their range 2. Females have similar coloration but duller plumage overall, and noticeably lack the black throat patch 2, 3. Although similar in size and appearance to some sparrow species, female Dickcissels can be distinguished by their longer bill and pale yellow eyebrows, malars, and breast. Distribution & Range: Wyoming lies outside and to the west of the core breeding range of Dickcissel, which is centered over the prairie grasslands of the Great Plains 2. However, the species is known for its random movements into grassland environments well outside of its primary breeding range, which can lead to extreme and unpredictable annual fluctuations in distribution and abundance in those areas 2. -

Status and Occurrence of Blue Grosbeak (Passerina Caerulea) in British Columbia. by Rick Toochin and Don Cecile. Introduction An

Status and Occurrence of Blue Grosbeak (Passerina caerulea) in British Columbia. By Rick Toochin and Don Cecile. Introduction and Distribution The Blue Grosbeak (Passerina caerulea) is a beautiful passerine found breeding from northern California, west and southern Nevada, southern Idaho, south-central Montana, south-central North Dakota, southwestern Minnesota, central and north-eastern Illinois, northwestern Indiana, northern Ohio, southern Pennsylvania, and south-eastern New York; south to Georgia, and central Florida, across the Gulf States away from the coast, throughout Texas, and west to Arizona (Beadle and Rising 2006). It is found rarely breeding south to northern Baja California. This species breeds south throughout Mexico, and is a resident species in the highlands and Pacific Lowlands of Central America; and in Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua to central Costa Rica (Howell and Webb 2010). The Blue Grosbeak is a migratory species throughout its North American range and moves south from its western range into Mexico and from the eastern United States across the Gulf of Mexico, throughout Mexico and south into Central America (Beadle and Rising 2006). This species has been reported in the Bahamas, the Greater Antilles, The Cayman and Swan Islands and Bermuda (Beadle and Rising 2006). The Blue Grosbeak winters in southern Baja California and northern Mexico, along the Gulf of Mexico, and south throughout Central America to central Panama with rare individuals wintering from the Gulf Coast of Florida north to New England (Beadle and Rising 2006, Howell and Webb 2010). The Blue Grosbeak is a casual vagrant species well north of its breeding range with many records from Atlantic Canada, southern Quebec, southern Ontario, and individual records from southern Saskatchewan (Godfrey 1986), and Wisconsin (Beadle and Rising 2006). -

Birds of Allerton Park

Birds of Allerton Park 2 Table of Contents Red-head woodpecker .................................................................................................................................. 5 Red-bellied woodpecker ............................................................................................................................... 6 Hairy Woodpecker ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Downy woodpecker ...................................................................................................................................... 8 Northern Flicker ............................................................................................................................................ 9 Pileated woodpecker .................................................................................................................................. 10 Eastern Meadowlark ................................................................................................................................... 11 Common Grackle......................................................................................................................................... 12 Red-wing blackbird ..................................................................................................................................... 13 Rusty blackbird ........................................................................................................................................... -

Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF CUBA Number 3 2020 Nils Navarro Pacheco www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com 1 Senior Editor: Nils Navarro Pacheco Editors: Soledad Pagliuca, Kathleen Hennessey and Sharyn Thompson Cover Design: Scott Schiller Cover: Bee Hummingbird/Zunzuncito (Mellisuga helenae), Zapata Swamp, Matanzas, Cuba. Photo courtesy Aslam I. Castellón Maure Back cover Illustrations: Nils Navarro, © Endemic Birds of Cuba. A Comprehensive Field Guide, 2015 Published by Ediciones Nuevos Mundos www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com [email protected] Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba ©Nils Navarro Pacheco, 2020 ©Ediciones Nuevos Mundos, 2020 ISBN: 978-09909419-6-5 Recommended citation Navarro, N. 2020. Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba. Ediciones Nuevos Mundos 3. 2 To the memory of Jim Wiley, a great friend, extraordinary person and scientist, a guiding light of Caribbean ornithology. He crossed many troubled waters in pursuit of expanding our knowledge of Cuban birds. 3 About the Author Nils Navarro Pacheco was born in Holguín, Cuba. by his own illustrations, creates a personalized He is a freelance naturalist, author and an field guide style that is both practical and useful, internationally acclaimed wildlife artist and with icons as substitutes for texts. It also includes scientific illustrator. A graduate of the Academy of other important features based on his personal Fine Arts with a major in painting, he served as experience and understanding of the needs of field curator of the herpetological collection of the guide users. Nils continues to contribute his Holguín Museum of Natural History, where he artwork and copyrights to BirdsCaribbean, other described several new species of lizards and frogs NGOs, and national and international institutions in for Cuba. -

Linking Migratory Songbird Declines with Increasing Precipitation and Brood Parasitism Vulnerability

fevo-08-536769 November 21, 2020 Time: 13:24 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 26 November 2020 doi: 10.3389/fevo.2020.536769 Not Singing in the Rain: Linking Migratory Songbird Declines With Increasing Precipitation and Brood Parasitism Vulnerability Kristen M. Rosamond1, Sandra Goded1, Alaaeldin Soultan2, Rachel H. Kaplan1,3, Alex Glass3,4, Daniel H. Kim3,5 and Nico Arcilla1,3,6* 1 International Bird Conservation Partnership, Monterey, CA, United States, 2 Department of Ecology, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden, 3 Crane Trust, Wood River, NE, United States, 4 Cooperative Wildlife Research Laboratory, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL, United States, 5 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Pierre, SD, United States, 6 Center for Great Plains Studies, University of Nebraska–Lincoln, Lincoln, NE, United States Few empirical studies have quantified relationships between changing weather and migratory songbirds, but such studies are vital in a time of rapid climate change. Climate change has critical consequences for avian breeding ecology, geographic Edited by: Mark C. Mainwaring, ranges, and migration phenology. Changing precipitation and temperature patterns University of Montana, United States affect habitat, food resources, and other aspects of birds’ life history strategies. Reviewed by: Such changes may disproportionately affect species confined to rare or declining Jose A. Masero, University of Extremadura, Spain ecosystems, such as temperate grasslands, which are among the most altered and Jennifer Anne -

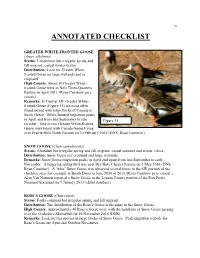

2016 Annotated Checklist of Birds on the Fort

16 ANNOTATED CHECKLIST GREATER WHITE-FRONTED GOOSE (Anser albifrons) Status: Uncommon but irregular spring and fall migrant, casual winter visitor. Distribution: Look for Greater White- fronted Geese on large wetlands and in cropland. High Counts: About 10 Greater White- fronted Geese were in Nels Three-Quarters Pasture in April 2011 (Ryan Cumbow pers. comm.). Remarks: In Central SD, Greater White- fronted Geese (Figure 15) are most often found mixed with large flocks of Canada or Snow Geese. White-fronted migration peaks in April and from late September to late Figure 15. October. One or two Greater White-fronted Geese were heard with Canada Geese flying over Prairie Hills North Pasture on 10 February 2015 (DNS, Ryan Cumbow). SNOW GOOSE (Chen caerulescens) Status: Abundant but irregular spring and fall migrant, casual summer and winter visitor. Distribution: Snow Geese use cropland and large wetlands. Remarks: Snow Goose migration peaks in April and again from late September to early November. A lingering spring bird was near Dry Hole Chester Pasture on 1 May 2014 (DNS, Ryan Cumbow). A “blue” Snow Goose was observed several times in the SW portion of the checklist area (for example at Booth Dam) in June 2010 or 2011 (Ryan Cumbow pers. comm.). Alan Van Norman reported a Snow Goose in the Lyman County portion of the Fort Pierre National Grassland on 5 January 2013 (eBird database). ROSS’S GOOSE (Chen rossii) Status: Fairly common but irregular spring and fall migrant. Distribution: The distribution of the Ross’s Goose is the same as the Snow Goose. High Counts: Approximately 40 Ross’s Geese were with the hundreds of Snow Geese passing over the Cookstove Shelterbelt on 10 November 2014 (DNS).