Chapter 2. Descriptive Statistics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

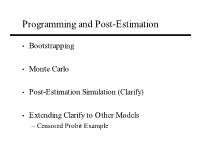

Programming in Stata

Programming and Post-Estimation • Bootstrapping • Monte Carlo • Post-Estimation Simulation (Clarify) • Extending Clarify to Other Models – Censored Probit Example What is Bootstrapping? • A computer-simulated nonparametric technique for making inferences about a population parameter based on sample statistics. • If the sample is a good approximation of the population, the sampling distribution of interest can be estimated by generating a large number of new samples from the original. • Useful when no analytic formula for the sampling distribution is available. B 2 ˆ B B b How do I do it? SE B = s(x )- s(x )/ B /(B -1) å[ åb =1 ] b=1 1. Obtain a Sample from the population of interest. Call this x = (x1, x2, … , xn). 2. Re-sample based on x by randomly sampling with replacement from it. 3. Generate many such samples, x1, x2, …, xB – each of length n. 4. Estimate the desired parameter in each sample, s(x1), s(x2), …, s(xB). 5. For instance the bootstrap estimate of the standard error is the standard deviation of the bootstrap replications. Example: Standard Error of a Sample Mean Canned in Stata use "I:\general\PRISM Programming\auto.dta", clear Type: sum mpg Example: Standard Error of a Sample Mean Canned in Stata Type: bootstrap "summarize mpg" r(mean), reps(1000) » 21.2973±1.96*.6790806 x B - x Example: Difference of Medians Test Type: sum length, detail Type: return list Example: Difference of Medians Test Example: Difference of Medians Test Example: Difference of Medians Test Type: bootstrap "mymedian" r(diff), reps(1000) The medians are not very different. -

The Cascade Bayesian Approach: Prior Transformation for a Controlled Integration of Internal Data, External Data and Scenarios

risks Article The Cascade Bayesian Approach: Prior Transformation for a Controlled Integration of Internal Data, External Data and Scenarios Bertrand K. Hassani 1,2,3,* and Alexis Renaudin 4 1 University College London Computer Science, 66-72 Gower Street, London WC1E 6EA, UK 2 LabEx ReFi, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, CESCES, 106 bd de l’Hôpital, 75013 Paris, France 3 Capegemini Consulting, Tour Europlaza, 92400 Paris-La Défense, France 4 Aon Benfield, The Aon Centre, 122 Leadenhall Street, London EC3V 4AN, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-(0)753-016-7299 Received: 14 March 2018; Accepted: 23 April 2018; Published: 27 April 2018 Abstract: According to the last proposals of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, banks or insurance companies under the advanced measurement approach (AMA) must use four different sources of information to assess their operational risk capital requirement. The fourth includes ’business environment and internal control factors’, i.e., qualitative criteria, whereas the three main quantitative sources available to banks for building the loss distribution are internal loss data, external loss data and scenario analysis. This paper proposes an innovative methodology to bring together these three different sources in the loss distribution approach (LDA) framework through a Bayesian strategy. The integration of the different elements is performed in two different steps to ensure an internal data-driven model is obtained. In the first step, scenarios are used to inform the prior distributions and external data inform the likelihood component of the posterior function. In the second step, the initial posterior function is used as the prior distribution and the internal loss data inform the likelihood component of the second posterior function. -

What Is Bayesian Inference? Bayesian Inference Is at the Core of the Bayesian Approach, Which Is an Approach That Allows Us to Represent Uncertainty As a Probability

Learn to Use Bayesian Inference in SPSS With Data From the National Child Measurement Programme (2016–2017) © 2019 SAGE Publications Ltd. All Rights Reserved. This PDF has been generated from SAGE Research Methods Datasets. SAGE SAGE Research Methods Datasets Part 2019 SAGE Publications, Ltd. All Rights Reserved. 2 Learn to Use Bayesian Inference in SPSS With Data From the National Child Measurement Programme (2016–2017) Student Guide Introduction This example dataset introduces Bayesian Inference. Bayesian statistics (the general name for all Bayesian-related topics, including inference) has become increasingly popular in recent years, due predominantly to the growth of evermore powerful and sophisticated statistical software. However, Bayesian statistics grew from the ideas of an English mathematician, Thomas Bayes, who lived and worked in the first half of the 18th century and have been refined and adapted by statisticians and mathematicians ever since. Despite its longevity, the Bayesian approach did not become mainstream: the Frequentist approach was and remains the dominant means to conduct statistical analysis. However, there is a renewed interest in Bayesian statistics, part prompted by software development and part by a growing critique of the limitations of the null hypothesis significance testing which dominates the Frequentist approach. This renewed interest can be seen in the incorporation of Bayesian analysis into mainstream statistical software, such as, IBM® SPSS® and in many major statistics text books. Bayesian Inference is at the heart of Bayesian statistics and is different from Frequentist approaches due to how it views probability. In the Frequentist approach, probability is the product of the frequency of random events occurring Page 2 of 19 Learn to Use Bayesian Inference in SPSS With Data From the National Child Measurement Programme (2016–2017) SAGE SAGE Research Methods Datasets Part 2019 SAGE Publications, Ltd. -

Basic Econometrics / Statistics Statistical Distributions: Normal, T, Chi-Sq, & F

Basic Econometrics / Statistics Statistical Distributions: Normal, T, Chi-Sq, & F Course : Basic Econometrics : HC43 / Statistics B.A. Hons Economics, Semester IV/ Semester III Delhi University Course Instructor: Siddharth Rathore Assistant Professor Economics Department, Gargi College Siddharth Rathore guj75845_appC.qxd 4/16/09 12:41 PM Page 461 APPENDIX C SOME IMPORTANT PROBABILITY DISTRIBUTIONS In Appendix B we noted that a random variable (r.v.) can be described by a few characteristics, or moments, of its probability function (PDF or PMF), such as the expected value and variance. This, however, presumes that we know the PDF of that r.v., which is a tall order since there are all kinds of random variables. In practice, however, some random variables occur so frequently that statisticians have determined their PDFs and documented their properties. For our purpose, we will consider only those PDFs that are of direct interest to us. But keep in mind that there are several other PDFs that statisticians have studied which can be found in any standard statistics textbook. In this appendix we will discuss the following four probability distributions: 1. The normal distribution 2. The t distribution 3. The chi-square (2 ) distribution 4. The F distribution These probability distributions are important in their own right, but for our purposes they are especially important because they help us to find out the probability distributions of estimators (or statistics), such as the sample mean and sample variance. Recall that estimators are random variables. Equipped with that knowledge, we will be able to draw inferences about their true population values. -

Practical Meta-Analysis -- Lipsey & Wilson Overview

Practical Meta-Analysis -- Lipsey & Wilson The Great Debate • 1952: Hans J. Eysenck concluded that there were no favorable Practical Meta-Analysis effects of psychotherapy, starting a raging debate • 20 years of evaluation research and hundreds of studies failed David B. Wilson to resolve the debate American Evaluation Association • 1978: To proved Eysenck wrong, Gene V. Glass statistically Orlando, Florida, October 3, 1999 aggregate the findings of 375 psychotherapy outcome studies • Glass (and colleague Smith) concluded that psychotherapy did indeed work • Glass called his method “meta-analysis” 1 2 The Emergence of Meta-Analysis The Logic of Meta-Analysis • Ideas behind meta-analysis predate Glass’ work by several • Traditional methods of review focus on statistical significance decades testing – R. A. Fisher (1944) • Significance testing is not well suited to this task • “When a number of quite independent tests of significance have been made, it sometimes happens that although few or none can be – highly dependent on sample size claimed individually as significant, yet the aggregate gives an – null finding does not carry to same “weight” as a significant impression that the probabilities are on the whole lower than would often have been obtained by chance” (p. 99). finding • Source of the idea of cumulating probability values • Meta-analysis changes the focus to the direction and – W. G. Cochran (1953) magnitude of the effects across studies • Discusses a method of averaging means across independent studies – Isn’t this what we are -

Statistical Power in Meta-Analysis Jin Liu University of South Carolina - Columbia

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 12-14-2015 Statistical Power in Meta-Analysis Jin Liu University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Educational Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Liu, J.(2015). Statistical Power in Meta-Analysis. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3221 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATISTICAL POWER IN META-ANALYSIS by Jin Liu Bachelor of Arts Chongqing University of Arts and Sciences, 2009 Master of Education University of South Carolina, 2012 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Educational Psychology and Research College of Education University of South Carolina 2015 Accepted by: Xiaofeng Liu, Major Professor Christine DiStefano, Committee Member Robert Johnson, Committee Member Brian Habing, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Senior Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Jin Liu, 2015 All Rights Reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my thanks to all committee members who continuously supported me in the dissertation work. My dissertation chair, Xiaofeng Liu, always inspired and trusted me during this study. I could not finish my dissertation at this time without his support. Brian Habing helped me with R coding and research design. I could not finish the coding process so quickly without his instruction. I appreciate the encouragement from Christine DiStefano and Robert Johnson. -

Descriptive Statistics Frequency Distributions and Their Graphs

Chapter 2 Descriptive Statistics § 2.1 Frequency Distributions and Their Graphs Frequency Distributions A frequency distribution is a table that shows classes or intervals of data with a count of the number in each class. The frequency f of a class is the number of data points in the class. Class Frequency, f 1 – 4 4 LowerUpper Class 5 – 8 5 Limits 9 – 12 3 Frequencies 13 – 16 4 17 – 20 2 Larson & Farber, Elementary Statistics: Picturing the World , 3e 3 1 Frequency Distributions The class width is the distance between lower (or upper) limits of consecutive classes. Class Frequency, f 1 – 4 4 5 – 1 = 4 5 – 8 5 9 – 5 = 4 9 – 12 3 13 – 9 = 4 13 – 16 4 17 – 13 = 4 17 – 20 2 The class width is 4. The range is the difference between the maximum and minimum data entries. Larson & Farber, Elementary Statistics: Picturing the World , 3e 4 Constructing a Frequency Distribution Guidelines 1. Decide on the number of classes to include. The number of classes should be between 5 and 20; otherwise, it may be difficult to detect any patterns. 2. Find the class width as follows. Determine the range of the data, divide the range by the number of classes, and round up to the next convenient number. 3. Find the class limits. You can use the minimum entry as the lower limit of the first class. To find the remaining lower limits, add the class width to the lower limit of the preceding class. Then find the upper class limits. 4. -

Flood Frequency Analysis Using Copula with Mixed Marginal Distributions

Flood frequency analysis using copula with mixed marginal distributions Project Report, Aug. 2007 Project Report August 2007 - 1 - Flood frequency analysis using copula with mixed marginal distributions Project Report, Aug. 2007 Prepared by and - 2 - Flood frequency analysis using copula with mixed marginal distributions Project Report, Aug. 2007 Abstract...................................................................................................................7 I. Introduction......................................................................................................8 II. Nonparametric method of estimating marginal distribution.................................14 II.1 Univariate kernel density estimation...........................................................14 II.2 Orthonormal series method.......................................................................17 III. The copula function.........................................................................................19 IV. Multivariate flood frequency analysis................................................................23 IV.1 Details of the case study............................................................................25 IV.2 Associations among flood characteristics.....................................................26 IV.3 Marginal distributions of flood characteristics..............................................29 IV.3.1 Parametric estimation.........................................................................30 IV.3.2 Nonparametric estimation...................................................................32 -

Formulas Used by the “Practical Meta-Analysis Effect Size Calculator”

Formulas Used by the “Practical Meta-Analysis Effect Size Calculator” David B. Wilson George Mason University April 27, 2017 1 Introduction This document provides the equations used by the on-line Practical Meta- Analysis Effect Size Calculator, available at: http://www.campbellcollaboration.org/resources/effect_size _input.php and http://cebcp.org/practical-meta-analysis-effect-size-calculator The calculator is a companion to the book I co-authored with Mark Lipsey, ti- tled “Practical Meta-Analysis,” published by Sage in 2001 (ISBN-10: 9780761921684). This calculator computes four effect size types: 1. Standardized mean difference (d) 2. Correlation coefficient (r) 3. Odds ratio (OR) 4. Risk ratio (RR) In addition to computing effect sizes, the calculator computes the associated variance and 95% confidence interval. The variance can be used to generate the w = 1=v weight for inverse-variancep weighted meta-analysis ( ) or the standard error (se = v). 2 Notation Notation commonly used through this document is presented below. Other no- tation will be defined as needed. 1 Formulas for “Practical Meta–Analysis Online Calculator” d Standardized mean difference effect size n1 Sample size for group 1 n2 Sample size for group 2 N Total sample size s1 Standard deviation for group 1 s2 Standard deviation for group 2 s Full sample standard deviation se1 Standard error for the mean of group 1 se2 Standard error for the mean of group 2 sgain Gain score standard deviation X1 Mean for group 1 X2 Mean for group 2 Xij Mean for subgroup i of group j ∆1 -

Categorical Data Analysis

Categorical Data Analysis Related topics/headings: Categorical data analysis; or, Nonparametric statistics; or, chi-square tests for the analysis of categorical data. OVERVIEW For our hypothesis testing so far, we have been using parametric statistical methods. Parametric methods (1) assume some knowledge about the characteristics of the parent population (e.g. normality) (2) require measurement equivalent to at least an interval scale (calculating a mean or a variance makes no sense otherwise). Frequently, however, there are research problems in which one wants to make direct inferences about two or more distributions, either by asking if a population distribution has some particular specifiable form, or by asking if two or more population distributions are identical. These questions occur most often when variables are qualitative in nature, making it impossible to carry out the usual inferences in terms of means or variances. For such problems, we use nonparametric methods. Nonparametric methods (1) do not depend on any assumptions about the parameters of the parent population (2) generally assume data are only measured at the nominal or ordinal level. There are two common types of hypothesis-testing problems that are addressed with nonparametric methods: (1) How well does a sample distribution correspond with a hypothetical population distribution? As you might guess, the best evidence one has about a population distribution is the sample distribution. The greater the discrepancy between the sample and theoretical distributions, the more we question the “goodness” of the theory. EX: Suppose we wanted to see whether the distribution of educational achievement had changed over the last 25 years. We might take as our null hypothesis that the distribution of educational achievement had not changed, and see how well our modern-day sample supported that theory. -

Chapter 10 -- Chi-Square Tests

Contents 10 Chi Square Tests 703 10.1 Introduction . 703 10.2 The Chi Square Distribution . 704 10.3 Goodness of Fit Test . 709 10.4 Chi Square Test for Independence . 731 10.4.1 Statistical Relationships and Association . 732 10.4.2 A Test for Independence . 734 10.4.3 Notation for the Test of Independence . 740 10.4.4 Reporting Chi Square Tests for Independence . 750 10.4.5 Test of Independence from an SPSS Program . 752 10.4.6 Summary . 763 10.5 Conclusion . 764 702 Chapter 10 Chi Square Tests 10.1 Introduction The statistical inference of the last three chapters has concentrated on statis- tics such as the mean and the proportion. These summary statistics have been used to obtain interval estimates and test hypotheses concerning popu- lation parameters. This chapter changes the approach to inferential statistics somewhat by examining whole distributions, and the relationship between two distributions. In doing this, the data is not summarized into a single measure such as the mean, standard deviation or proportion. The whole dis- tribution of the variable is examined, and inferences concerning the nature of the distribution are obtained. In this chapter, these inferences are drawn using the chi square distribu- tion and the chi square test. The ¯rst type of chi square test is the goodness of ¯t test. This is a test which makes a statement or claim concerning the nature of the distribution for the whole population. The data in the sam- ple is examined in order to see whether this distribution is consistent with the hypothesized distribution of the population or not. -

Mean, Median, Mode, Geometric Mean and Harmonic Mean for Grouped Data

Practical.3 Measures of central tendency – mean, median, mode, geometric mean and harmonic mean for grouped data Arithmetic mean or mean Grouped Data The mean for grouped data is obtained from the following formula: Where x = the mid-point of individual class f = the frequency of individual class N = the sum of the frequencies or total frequencies. Short-cut method Where A = any value in x N = total frequency c = width of the class interval Example 1 Given the following frequency distribution, calculate the arithmetic mean Marks : 64 63 62 61 60 59 Number of Students : 8 18 12 9 7 6 1 Solution X f fx d=x-A fd 64 8 512 2 16 63 18 1134 1 18 62 12 744 0 0 61 9 549 -1 -9 60 7 420 -2 -14 59 6 354 -3 -18 60 3713 -7 Direct method Short-cut method Here A = 62 Example 2 For the frequency distribution of seed yield of sesamum given in table calculate the mean yield per plot. Yield per 64.5-84.5 84.5-104.5 104.5-124.5 124.5-144.5 plot in(in g) No of 3 5 7 20 plots 2 Solution Yield ( in g) No of Plots (f) Mid X fd 64.5-84.5 3 74.5 -1 -3 84.5-104.5 5 94.5 0 0 104.5-124.5 7 114.5 1 7 124.5-144.5 20 134.5 2 40 Total 35 44 A=94.5 The mean yield per plot is Median Grouped data In a grouped distribution, values are associated with frequencies.