The Entertaining Way to Behavioral Change: Fighting HIV with MTV∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Until That Song Is Born”: an Ethnographic Investigation of Teaching and Learning Among Collaborative Songwriters in Nashville

“UNTIL THAT SONG IS BORN”: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC INVESTIGATION OF TEACHING AND LEARNING AMONG COLLABORATIVE SONGWRITERS IN NASHVILLE By Stuart Chapman Hill A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Music Education—Doctor of Philosophy 2016 ABSTRACT “UNTIL THAT SONG IS BORN”: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC INVESTIGATION OF TEACHING AND LEARNING AMONG COLLABORATIVE SONGWRITERS IN NASHVILLE By Stuart Chapman Hill With the intent of informing the practice of music educators who teach songwriting in K– 12 and college/university classrooms, the purpose of this research is to examine how professional songwriters in Nashville, Tennessee—one of songwriting’s professional “hubs”—teach and learn from one another in the process of engaging in collaborative songwriting. This study viewed songwriting as a form of “situated learning” (Lave & Wenger, 1991) and “situated practice” (Folkestad, 2012) whose investigation requires consideration of the professional culture that surrounds creative activity in a specific context (i.e., Nashville). The following research questions guided this study: (1) How do collaborative songwriters describe the process of being inducted to, and learning within, the practice of professional songwriting in Nashville, (2) What teaching and learning behaviors can be identified in the collaborative songwriting processes of Nashville songwriters, and (3) Who are the important actors in the process of learning to be a collaborative songwriter in Nashville, and what roles do they play (e.g., gatekeeper, mentor, role model)? This study combined elements of case study and ethnography. Data sources included observation of co-writing sessions, interviews with songwriters, and participation in and observation of open mic and writers’ nights. -

Wirecast for Youtube User Guide

Mac 1.1 User’s Guide %FDFNCFS 3 Contents Preface 7 Copyright Notice 7 Customer Support 7 Introduction 9 Introduction 9 Wirecast for YouTube Features 10 Getting Started 10 Two Ways to Use Wirecast for YouTube 10 Subject Is Operator 10 Subject Plus Operator 10 Main Window 11 Preview 14 Getting Started 15 Introduction 15 Creating a Live Event 16 The Main Window 16 What is a Shot? 16 Adding a Shot 17 Transitions and Go Button 18 Transitions 18 The Go Button 20 Creating Composite Shots 23 Composite Shots 23 Title Overlays 24 Live Streaming 27 Setup a YouTube Event 27 Sign in to YouTube 27 Connect to YouTube 30 4 Contents Adding Media 33 Introduction 33 Source Media Panels 34 Adding Media Files 35 Adding Cameras 36 Adding Composite Sources 36 Adding Overlays 38 Adding Desktop Shots 38 GIF and Transparency 38 Movies 39 Problems Showing Movie Types 39 MPEG-1 Audio 39 AVI Video 39 Windows Media 39 Real Media 39 Using Overlays 41 Introduction 41 Adding Media Overlays 42 Adding Title Overlays 42 Using Audio Controls 45 Introduction 45 The Audio Panel 46 Assigning Audio sources 47 Master Audio 48 Streaming 49 Introduction 49 Live Streaming 50 Setup a YouTube Event 50 Sign in to YouTube 50 Connect to YouTube 53 Flash Log Files 54 User Interface 55 Introduction 55 Wirecast for YouTube Menu 56 File Menu 56 Sources Menu 56 Window Menu 57 Tools Menu 57 Help Menu 57 Keyboard Short-cuts 57 December, 2012 Wirecast for YouTube User’s Guide | 96822 Contents 5 Using the Source Settings 61 Introduction 61 Topics 61 Overview 62 System Devices 63 Desktop Presenter -

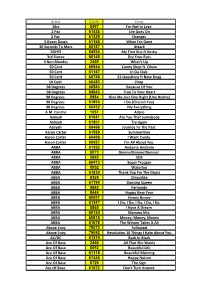

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Broadcasters and the Broadcasters and the Internet

Broadcasters and the Broadcasters and the Internet Internet EBU Members’ Internet Presence Distribution Strategies Online Consumption Trends Social Networking and Video Sharing Communities November 2007 European Broadcasting Union Strategic Information Service (SIS) L’Ancienne-Route 17A CH-1218 Grand-Saconnex Switzerland Phone +41 (0) 22 717 21 11 Fax +41 (0)22 747 40 00 www.ebu.ch/sis European Broadcasting Union l Strategic Information Service Broadcasters and the Internet EBU Members' Internet Presence Distribution Strategies Online Consumption Trends Social Networking and Video Sharing Communities November 2007 The Report Staff This report was produced by the Strategic Information Service of the EBU. Editor: Alexander Shulzycki Production Editor: Anna-Sara Stalvik Principal Researcher: Anna-Sara Stalvik Special appreciation to: Danish Radio and Television (DR) Swedish Television (SVT) Swedish Radio (SR) Cover Design: Philippe Juttens European Broadcasting Union Telephone: +41 22 717 2111 Address: L'Ancienne-Route 17A, 1218 Geneva, Switzerland SIS web-site: www.ebu.ch/director_general/sis.php SIS contact e-mail: [email protected] BROADCASTERS AND THE INTERNET TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................. 1 OVERVIEW .............................................................................................................................1 1. The general Internet landscape: usage, websites, advertising ............................................ -

The Entertaining Way to Behavioral Change: Fighting Hiv with Mtv

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES THE ENTERTAINING WAY TO BEHAVIORAL CHANGE: FIGHTING HIV WITH MTV Abhijit Banerjee Eliana La Ferrara Victor H. Orozco-Olvera Working Paper 26096 http://www.nber.org/papers/w26096 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 July 2019 This research is part of the entertainment-education program of the World Bank’s Development Impact Evaluation Department (DIME), part of the Development Economics Research Group. We thank Oriana Bandiera, Michael Callen, Ruixue Jia, Gaia Narciso, Ricardo Perez-Truglia, Devesh Rustagi and seminar participants at IIES, LSE, Toulouse, Trinity College Dublin, University of Bonn, UCLA, UC San Diego, University of Manheim, University of Oslo, University of Amsterdam, University of Southern California, Yale, UPF, PSE, Wharton and BREAD 2018 conference for helpful comments. Laura Costica and Edwin Ikuhoria did a superb job as research and field coordinators. Tommaso Coen, Viola Corradini, Dante Donati, Francesco Loiacono, Awa Ambra Seck, Sara Spaziani and Silvia Barbareschi provided excellent research assistance. This study was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the World Bank i2i Trust Fund. La Ferrara acknowledges financial support from ERC Advanced Grant ASNODEV. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2019 by Abhijit Banerjee, Eliana La Ferrara, and Victor H. Orozco-Olvera. All rights reserved. -

Karaoke with a Message – August 16, 2019 – 8:30PM

Another Protest Song: Karaoke with a Message – August 16, 2019 – 8:30PM a project of Angel Nevarez and Valerie Tevere for SOMA Summer 2019 at La Morenita Canta Bar (Puente de la Morena 50, 11870 Ciudad de México, MX) karaoke provided by La Morenita Canta Bar songbook edited by Angel Nevarez and Valerie Tevere ( ) 18840 (Ghost) Riders In The Sky Johnny Cash 10274 (I Am Not A) Robot Marina & Diamonds 00005 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 17636 (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 15910 (I Want To) Thank You Freddie Jackson 05545 (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees 06305 (It's) A Beautiful Mornin' Rascals 19116 (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon 15128 (Keep Feeling) Fascination Human League 04132 (Reach Up For The) Sunrise Duran Duran 05241 (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay Otis Redding 17305 (Taking My) Life Away Default 15437 (Who Says) You Can't Have It All Alan Jackson # 07630 18 'til I Die Bryan Adams 20759 1994 Jason Aldean 03370 1999 Prince 07147 2 Legit 2 Quit MC Hammer 18961 21 Guns Green Day 004-m 21st Century Digital Boy Bad Religion 08057 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 00714 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band 01379 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 14375 3 Strange Days School Of Fish 08711 4 Minutes Madonna 08867 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake 09981 4 Minutes Avant 18883 5 Miles To Empty Brownstone 13317 500 Miles Peter Paul & Mary 00082 59th Street Bridge Song Simon & Garfunkel 00384 9 To 5 Dolly Parton 08937 99 Luftballons Nena 03637 99 Problems Jay-Z 03855 99 Red Balloons Nena 22405 1-800-273-8255 -

Section 3: Safe Driving

Slow down as you approach toll plazas. Be extra cautious as you approach, enter, and depart toll plazas. There may be other drivers changing lanes and/or toll employees crossing the lanes. Section 3: Some toll roads have high speed lanes reserved for vehicles Safe Driving with E-ZPass transponders. Do not enter those lanes unless you have a transponder. However, if you do enter one of those lanes by mistake, do not stop. Stopping is unsafe and could cause a rear-end crash. Cameras will photograph the car’s license plate number and the registered vehicle’s owner will be billed for the toll. A painted curb means that you must follow special rules to park there. Check with the locality for specific meanings. Generally, the colors on the curb mean: White — Stop only long enough to pick up or drop off passengers. Yellow — Stop only long enough to load or unload. Stay with your car. Red — Do not stop, stand or park. Every time you get behind the wheel, you accept responsibility for your actions. You must obey Virginia’s traffic laws, and ensure the safety of you, your passengers, and other motorists, pedestrians and bicyclists on the roadways. In this section you’ll learn about: Hand Position Hand position Sit straight but relaxed and place your hands on the steering Speed limits wheel. If your steering wheel were a clock, your hands should Stopping be at the 8 o’clock and 4 o’clock positions. Hold the wheel Yielding the right-of-way with your fingers and thumbs. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Crush Garbage 1990 (French) Leloup (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue 1994 Jason Aldean (Ghost) Riders In The Sky The Outlaws 1999 Prince (I Called Her) Tennessee Tim Dugger 1999 Prince And Revolution (I Just Want It) To Be Over Keyshia Cole 1999 Wilkinsons (If You're Not In It For Shania Twain 2 Become 1 The Spice Girls Love) I'm Outta Here 2 Faced Louise (It's Been You) Right Down Gerry Rafferty 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue The Line 2 On (Explicit) Tinashe And Schoolboy Q (Sitting On The) Dock Of Otis Redding 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc The Bay 20 Years And Two Lee Ann Womack (You're Love Has Lifted Rita Coolidge Husbands Ago Me) Higher 2000 Man Kiss 07 Nov Beyonce 21 Guns Green Day 1 2 3 4 Plain White T's 21 Questions 50 Cent And Nate Dogg 1 2 3 O Leary Des O' Connor 21st Century Breakdown Green Day 1 2 Step Ciara And Missy Elliott 21st Century Girl Willow Smith 1 2 Step Remix Force Md's 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 1 Thing Amerie 22 Lily Allen 1, 2 Step Ciara 22 Taylor Swift 1, 2, 3, 4 Feist 22 (Twenty Two) Taylor Swift 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 22 Steps Damien Leith 10 Million People Example 23 Mike Will Made-It, Miley 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan Cyrus, Wiz Khalifa And 100 Years Five For Fighting Juicy J 100 Years From Now Huey Lewis And The News 24 Jem 100% Cowboy Jason Meadows 24 Hour Party People Happy Mondays 1000 Stars Natalie Bassingthwaighte 24 Hours At A Time The Marshall Tucker Band 10000 Nights Alphabeat 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan 24 Hours From You Next Of Kin 1-2-3 Len Berry 2-4-6-8 Motorway Tom Robinson Band 1234 Sumptin' New Coolio 24-7 Kevon Edmonds 15 Minutes Rodney Atkins 25 Miles Edwin Starr 15 Minutes Of Shame Kristy Lee Cook 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash 16th Avenue Lacy J Dalton 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 18 And Life Skid Row 29 Nights Danni Leigh 18 Days Saving Abel 3 Britney Spears 18 Til I Die Bryan Adams 3 A.M. -

DOCTEUR DE L'université DE BORDEAUX Functionalization Of

THÈSE PRÉSENTÉE POUR OBTENIR LE GRADE DE DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITÉ DE BORDEAUX ÉCOLE DOCTORALE DES SCIENCES CHIMIQUES SPÉCIALITÉ: Polymères Par Jérémie GRANGE Functionalization of Polyisoprene : Toward the mimic of Natural Rubber Fonctionnalisation de Polyisoprène : Vers un modèle du caoutchouc naturel Sous la direction de : Dr. Frédéric PERUCH et Pr. Stéphane GRELIER Co-encadrant : Dr. Rachid MATMOUR Soutenue le 23 janvier 2018 Membres du jury : Mme. PASETTO, Pamela Maître de conférences, Université du Maine Rapporteur M. CAILLOL, Sylvain Chargé de recherche CNRS, Université de Montpellier Rapporteur M. MATMOUR, Rachid Docteur, Michelin (MFPM) Examinateur M. BONFILS, Frédéric Chercheur, CIRAD Examinateur M. PERUCH, Frédéric Directeur de recherche CNRS, Université de Bordeaux Co-directeur M. GRELIER, Stéphane Professeur, Université de Bordeaux Co-directeur M. CARLOTTI, Stéphane Professeur, Bordeaux INP Président Pendant la rédaction de ce manuscrit, les titres suivants ont été écoutés: A Perfect Circle Chez Vous Flume Rose Le Père Never Be Like You Blue Charlie Foals Imagine L’Anticonformisme London Thunder Adham Shaikh Bon Iver Night Swimmers Water Prayer Holocene Albatross Air Skinny love Mountain At My Gates Alpha Beta Gaga Brigitte Inhaleur Sexy Boy Battez-vous Spanish Sahara Alanis Morissette Ma Benz’ Two Step Twice King Of Pain BRNS GoGo Penguin Alt-J Many Chances All Res Tessellate Interlude Hopopono Archive Slow Heart Branches Break Stay Tribal Bruce Springsteen Good Charlotte The False Foundation Streets of Philadelphia The Anthem -

Karaoke List

Artist Code Song 10cc 8497 I'm Not In Love 2 Pac 61426 Life Goes On 2 Pac 61425 Changes 3 Doors Down 61165 When I'm Gone 30 Seconds To Mars 60147 Attack 3OH!3 84954 My First Kiss ft Kesha 3rd Storee 60145 Dry Your Eyes 4 Non Blondes 2459 What's Up 50 Cent 60944 Candy Shop ft. Olivia 50 Cent 61147 In Da Club 50 Cent 60748 21 Questions ft Nate Dogg 50 Cent 60483 Pimp 98 Degrees 60543 Because Of You 98 Degrees 84943 True To Your Heart 98 Degrees 8984 Give Me Just One Night (Una Noche) 98 Degrees 61890 I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees 60332 My Everything A.M. Canche 1051 Adoro Aaliyah 61681 Are You That Somebody Aaliyah 61801 Try Again Aaliyah 60468 Journey To The Past Aaron Carter 61588 Summertime Aaron Carter 60458 I Want Candy Aaron Carter 60557 I'm All About You ABBA 61352 Andante Andante ABBA 8073 Gimme!Gimme!Gimme! ABBA 2692 SOS ABBA 60413 Super Trooper ABBA 8952 Waterloo ABBA 61830 Thank You For The Music ABBA 8369 Chiquitita ABBA 61199 Dancing Queen ABBA 8842 Fernando ABBA 8444 Happy New Year ABBA 60001 Honey Honey ABBA 61347 I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do ABBA 8865 I Have A Dream ABBA 60134 Mamma Mia ABBA 60818 Money, Money, Money ABBA 61678 The Winner Takes It All Above Envy 79073 Followed Above Envy 79092 Revolution 10 Things I Hate About You AC/DC 61319 Back In Black Ace Of Base 2466 All That She Wants Ace Of Base 8592 Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 61118 Beautiful Morning Ace Of Base 61346 Happy Nation Ace Of Base 8729 The Sign Ace Of Base 61672 Don't Turn Around Acid House Kings 61904 This Heart Is A Stone Acquiesce 60699 Oasis Adam