Corky: Called the Meeting to Order, Noted NOAA Was Not Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FISHING � June 24, 2005 Texas’ Premier Outdoor Newspaper Volume I, Issue 21 � Sharks in the Gulf See Page 8 $1.75

FISHING * June 24, 2005 Texas’ Premier Outdoor Newspaper Volume I, Issue 21 * Sharks in the Gulf See page 8 $1.75 www.lonestaroutdoornews.com INSIDE HUNTING NEWS Rock-solid opportunity awaits savvy jetty fishermen By John N. Felsher t Sabine Pass, two rock jetties dating back to 1900 extend into the Gulf of Mexico at the Texas-Louisiana state line, creating a fish magnet for reds, sheepshead and black drum. A Like artificial reefs, jetties attract many types of fish because they pro- vide outstanding cover for various species. Crabs and shrimp crawl over the rocks. Small fish congregate to feed upon algae growing on the rocks and plank- ton stacked there by currents. Of course, big fish gather where they find bait. The Texas Parks and Wildlife The East Jetty, on the Louisiana side of the pass, extends for about 4.7 miles. Commission has once again Since Texas Point thrusts farther out into the Gulf, the West Jetty runs 4.1 miles. closed the state’s borders to Between the rocks, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers maintains the channel at imported deer. See page 6 Continued on page 11 Nationally known outdoor writer Bob Brister dies. Brister wrote for the Houston Chronicle and Field & Stream. He was 77. See page 6 FISHING NEWS Game wardens are using thermal imaging devices to help them HERE COMES THE SUN: Anglers try their luck at daybreak on a Texas jetty fishing for species such as trout, reds and sheepsheads. catch illegal fishing activity. See page 9 Alligators move in on anglers Ducks call Texas home populations in Texas have been Call them bluegills or bream. -

Florida Fishing Regulations

2009–2010 Valid from July 1, 2009 FLORIDA through June 30, 2010 Fishing Regulations Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission FRESHWATER EDITION MyFWC.com/Fishing Tips from the Pros page 6 Contents Web Site: MyFWC.com Visit MyFWC.com/Fishing for up-to- date information on fishing, boating and how to help ensure safe, sus- tainable fisheries for the future. Fishing Capital North American Model of of the World—Welcome .........................2 Wildlife Conservation ........................... 17 Fish and wildlife alert reward program Florida Bass Conservation Center ............3 General regulations for fish management areas .............................18 Report fishing, boating or hunting Introduction .............................................4 law violations by calling toll-free FWC contact information & regional map Get Outdoors Florida! .............................19 1-888-404-FWCC (3922); on cell phones, dial *FWC or #FWC Freshwater fishing tips Specific fish management depending on service carrier; or from the pros..................................... 6–7 area regulations ............................18–24 report violations online at Northwest Region MyFWC.com/Law. Fishing license requirements & fees .........8 North Central Region Resident fishing licenses Northeast Region Nonresident fishing licenses Southwest Region Lifetime and 5-year licenses South Region Freshwater license exemptions Angler’s Code of Ethics ..........................24 Methods of taking freshwater fish ..........10 Instant “Big Catch” Angler Recognition -

Official Rules of Competition

OFFICIAL RULES OF COMPETITION C1. The following rules shall apply to all Bassmaster Elite and Bassmaster Classic events except that (i) rules for special tournaments may differ from those contained herein and (ii) these rules may be changed by B.A.S.S. immediately upon notice by B.A.S.S. to its members which notice may be published on the B.A.S.S. Internet site at www.bassmaster.com. Interpretation and enforcement of these rules shall be left exclusively to the Tournament Director or his/her designee at a tournament. In the event of a rule violation, the Tournament Director or rules committee may impose such sanctions, as deemed appropriate by them, including, without limitation, disqualification, and forfeiture of prizes, entry fee and prohibition from participation in subsequent tournaments. Subject to the appeal process set forth in paragraph 22, below, the decision of the Tournament Director, his/her designee, or the rules committee shall be final in all matters. Elite Series Pros are required to police themselves each competition day and must sign a Rules Adherence Form. If a pro has a concern regarding his catch he should not sign off on rules adherence, weigh his fish, and consult with rules officials immediately after weigh in. Anglers who sign off to full adherence and later found guilty of a rules violation MAY BE DISQUALIFIED from the tournament. Anglers not signing official score card will not start next official competition day unless directed by tournament officials. Penalties for rules violations may include the following: (a) reduction of competition hours as determined by the Tournament Director (b) loss of one or more fish in question. -

Eddies Reflections on Fisheries Conservation Departments Headwaters 3 American Fishes 10 Watermarks 4 Meanders 30 Eddies Pioneers 8 Vol

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Winter 2008 Eddies Reflections on Fisheries Conservation Departments Headwaters 3 American Fishes 10 Watermarks 4 Meanders 30 Eddies Pioneers 8 Vol. 1, No. 4 Headwaters Publisher Features Gary Frazer, Assistant Director U.S.Fish and Wildlife Service No Trout Left A Whole Different Partnerships get it done for Fisheries Conservation Fisheries and Habitat Conservation Behind–12 Animal–22 By Gary Frazer Mike Stempel Ben Ikenson Editor management agencies. Similarly, activities in uplands Craig Springer far removed from any pool-riffle-run complex influence stream fish habitats, so partnerships with landowners, Contributing writers A Scout’s Mission to Pharmaceuticals regulators, and construction agencies accomplish long- Lee Allen Marilyn O’Leary term conservation. That notion is articulated in the story Angela Carrillo Scott Robinson Save the Mojave Tui for Fish–24 Dave Erdahl Ashley Spratt Craig Springer “Southeast Aquatic Resources Partnership” by Scott Chub–14 Robinson and Marilyn O’Leary. They discuss coordinated Doug Grassian E. Peter Steenstra Bob Mazzuca Ben Ikenson Mark Steingraeber fisheries conservation over a 14-state area. Joyce Johnson Mike Stempel Abigail Lynch Judy Toppins Sport Fish Restoration United Front Against “Many hands make light work,” wrote English scribe Madeleine Lyttle Jenny Walker Program–16 Invasives–26 John Heywood in 1546. Light work comes from good Mark Madison Stephanie West Joyce Johnson Ashley Spratt Bob Mazzuca Mary Jane Williamson partnerships. During my time in Missouri, we created Howard Frank Mosher what I considered a genuinely good partnership with USFWS the Missouri Department of Conservation, the Natural Editorial Advisors The Southeast S.H.A.R.E. -

Eddies Reflections on Fisheries Conservation

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Summer 2009 Eddies Reflections on Fisheries Conservation 45560_USGP.indd 1 9/4/09 4:14:20 AM Departments Headwaters 3 American Fishes 10 Watermarks 4 Meanders 30 Eddies Pioneers 8 Vol. 2, No. 2 Publisher Features Bryan Arroyo, Assistant Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Dancing with What’s B’low–24 Fisheries and Habitat Conservation Reservoirs–12 Ryck Lydecker Dr. Karl Hess Executive Editor Stuart Leon, Ph.D. Deputy Editor Richard Christian Jurassic Pork–16 The Relevance Craig Springer of Creel Surveys Editor to Fisheries Craig Springer Conservation–26 Contributing writers Bob Wattendorf Meredith Bartron Thomas McCoy Reservoirs on Barry Bolton Michael Montoya the American John Bryan Jeffery Powell Dan Burleson Randi Sue Smith Landscape–20 Dr. Karl Hess Joe Starinchak Chris Horton Chris Horton Denise Wagner David Klinger Bob Wattendorf Sarah Leon Stephanie West Ryck Lydecker Editorial Advisors Mark Brouder, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Ryck Lydecker, Boat Owners Association of the United States Mark Maskill, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Hal Schramm, Ph.D., U.S. Geological Survey Michael Smith, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (retired) Denise Wagner, Wonders of Wildlife Museum Assistant Regional Directors – Fisheries Dan Diggs, Pacific Region John Engbring, Pacific Southwest Region Jaime Geiger, Ph.D., Northeast Region Linda Kelsey, Southeast Region Mike Oetker, Southwest Region LaVerne Smith, Alaska Region Mike Stempel, Mountain–Prairie Region Mike Weimer, Great Lakes–Big Rivers Region Springer Contact For subscription information visit our web site, Craig www.fws.gov/eddies, email [email protected], Reservoirs provide tremendous angling opportunities call 505 248-6867, or write to: throughout the U.S. -

Copyrighted Material

bindex.qxp 8/15/06 10:46 AM Page 303 INDEX Page numbers in italics indicate photos. ABC, 22, 203. See also ESPN Scott and, 146–151 Abu Garcia, 152 tournament rules, 264–270, 272 Alabama Web site of, 56 bass fishing popularity in, 240 See also ESPN; individual names of events 2007 Citgo Bassmaster Classic, 302 bass Deep Sea Fishing Rodeo, 137–138 bass fishing popularity, 239–244 River Classic, 171–174 black bass, 124, 129, 146, 209 Water Improvement Commission, 154 fish classification and, 121–128 Alan, Keith, 226, 229, 278 habitat of, 125, 127, 131 2005 Bassmaster Classic, 37, 41, 49–56, spawning by, 247–254, 267–270, 276, 59, 63–65, 67, 71, 79–81, 109–113, 298–299 115–118 See also sportfishing 2006 Bassmaster Classic, 255, 257, 262, Bass Anglers Sportsman Society 287, 289 (BASS), 147, 151–157. See also BASS All-American Invitational Bass Tourna- bass boats, 197–202. See also boats; individ- ments, 148–151 ual names of manufacturers Allegheny River, 21, 21, 25, 28–30, 38, 76 Bass Boss (Boyle), 160, 166 All Things Considered (National Public BassCenter (ESPN) Radio), 20 2005 Bassmaster Classic, 43, 62, 63, 67, American Fisheries Society (AFS), 133–134 69, 82, 84–85, 95, 267 American Sportfishing Association (ASA), 2006 Bassmaster Classic, 271, 284, 294 209–212 See also ESPN Anderson, Lou, 28–30, 99 bassfan.com, 293, 296–297 Argenas, Aaron, 105, 105–106, 116 Bass Federation, 153–155, 283 Argenas, Nick, 105, 105–106 Bassmaster Classic, 143 Arledge, Roone, 100 inception of (1971), 158–166, 159, 162, Art of Angling, The (Brookes), 124–125 164 location -

MARKETPLACE 2021 Bassmaster Marketplace National Advertising Rates

2021 MARKETPLACE 2021 Bassmaster Marketplace National Advertising Rates 515,000 RATE BASE 9x/year FREQUENCYRATE BASE: 500,000 FREQUENCY: 9x/year Bassmaster Magazine Launched in 1968 as the membership magazine of the Bass Anglers Sportsman Society, Bassmaster is the ultimate authority on bass fishing for anglers of every skill level. Each issue is a must-read for a broad community of fishing enthusiasts covering topics such as: The Worldwide Authority On Bass Fishing Classic Preview 2020 • How-to fishing techniques • The latest new gear options and gear overviews • Suggestions of the best places to fish • Interviews with pro anglers • The science behind fishing and more 2021 RATES 1971 2020 Unit Size 1X 3X 6X 9X Page Page $9,930 $9,630 $9,220 $8,730 ◗ Legends Look Back ◗ Fan-a-palooza Largemouth 1/₂ $5,450 $5,290 $5,060 $4,790 ◗ Favorite Moments Smallmouth 1/₄ $2,720 $2,650 $2,540 $2,410 Crappie 1/₈ $1,370 $1,320 $1,270 $1,200 Who Will Win On Breaking Down The Big G? Guntersville Shad 1/₁₆ $690 $660 $630 $590 All orders are noncancelable after closing date. No penalty for ads that bleed. MARKETP 2021 Bassmaster Marketplace Advertising Due Dates Estimated Advertising Ad Material Inserts Begin In-Home Closing Due Due Mailing (Start) Jan/Feb 11/18/20 11/20/20 12/04/20 12/20/20 1/05/21 Classic Preview 1/04/21 1/06/21 1/15/21 1/31/21 2/13/21 March 1/25/21 1/28/21 2/05/21 2/21/21 3/06/21 April 2/15/21 2/18/21 2/26/21 3/14/21 3/27/21 May 3/15/21 3/23/21 4/02/21 4/18/21 5/01/21 June 4/14/21 4/16/21 4/30/21 5/16/21 5/29/21 July/Aug 5/12/21 5/14/21 -

Sixty-Second Annual Report (2011) of the Gulf States Marine

The GULF STATES MARINE FISHERIES COMMISSION is an organization of the five states whose coastal waters are the Gulf of Mexico. This Compact, authorized under Public Law 81‑66, was signed by the representatives of the Governors of the five Gulf States on July 16, 1949, at Mobile, Alabama. The Commission’s principal objectives are the conservation, development, and full utilization of the fishery resources of the Gulf of Mexico to provide food, employment, income, and recreation to the people of these United States. GULF STATES MARINE FISHERIES COMMISSION Sixty‑Second Annual Report (2011) to the Congress of the United States and to the Governors and Legislators of Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas Presented in compliance with the terms of the Compact and State Enabling Acts Creating such Commission and Public Law 66‑81st Congress assenting thereto. Edited by: Debora K. McIntyre and Steven J. VanderKooy Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission 2404 Government St. Ocean Springs, Mississippi 39564 (228) 875‑5912 www.gsmfc.org Preserving the Past ▪ Planning the Future ▪ A Cooperative Effort Charles H. Lyles Award The Charles H. Lyles Award is awarded annually by the Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission (GSMFC) to an individual, agency, or organization which has contributed to the betterment of the fisheries of the Gulf of Mexico through significant biological, industrial, legislative, enforcement, or administrative activities. The recipient is selected by the full Commission from open nominations at the spring March meeting. The selection is by secret ballot with the highest number of votes being named the recipient. The recipient is awarded the honor at the annual meeting in October. -

2021 Elite Series Rules

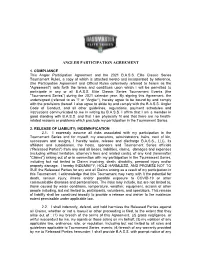

ANGLER PARTICIPATION AGREEMENT 1. COMPLIANCE This Angler Participation Agreement and the 2021 B.A.S.S. Elite Classic Series Tournament Rules, a copy of which is attached hereto and incorporated by reference, (the Participation Agreement and Official Rules collectively referred to herein as the “Agreement”) sets forth the terms and conditions upon which I will be permitted to participate in any or all B.A.S.S. Elite Classic Series Tournament Events (the “Tournament Series”) during the 2021 calendar year. By signing this Agreement, the undersigned (referred to as “I” or “Angler”), hereby agree to be bound by and comply with the provisions thereof. I also agree to abide by and comply with the B.A.S.S. Angler Code of Conduct, and all other guidelines, regulations, payment schedules and instructions communicated to me in writing by B.A.S.S. I affirm that I am a member in good standing with B.A.S.S. and that I am physically fit and that there are no health- related reasons or problems which preclude my participation in the Tournament Series. 2. RELEASE OF LIABILITY; INDEMNIFICATION 2.1. I expressly assume all risks associated with my participation in the Tournament Series and for myself, my executors, administrators, heirs, next of kin, successors and assigns, I hereby waive, release and discharge B.A.S.S., LLC, its affiliates and subsidiaries, the hosts, sponsors and Tournament Series officials (“Released Parties”) from any and all losses, liabilities, claims, damages and expenses (including without limitation, attorney’s fees and related costs), of any kind (hereinafter “Claims”) arising out of or in connection with my participation in the Tournament Series, including but not limited to Claims involving, death, disability, personal injury and/or property damage. -

Bassmasterâ Tournament Trail

Official Rules Bassmaster Opens Effective January 1, 2021 Participation Agreement Angler Participation Agreement and Release of Liability HAVING ACQUAINTED MYSELF WITH THE RULES AND REQUIREMENTS IN THIS BOOKLET, I HAVE SIGNED AND DATED THE PARTICIPATION AGREEMENT. I WILL MAIL OR FAX THE COMPLETED PARTICIPATION AGREEMENT AND COMPLETE THE ONLINE ENTRY FORM BY THE DEADLINE DATES PROVIDED BY B.A.S.S. MY REGISTRATION IS NOT COMPLETE UNTIL B.A.S.S. ACKNOWLEDGES RECEIPT AND ACCEPTANCE OF ALL REQUIRED DOCUMENTS. THE TOURNAMENT DIRECTOR RESERVES THE RIGHT TO REJECT MY APPLICATION FOR ANY REASON AND, UPON SUCH REJECTION, TO REFUND THE DEPOSIT OR ENTRY FEE. P1. COMPLIANCE WITH RULES By signing this agreement, I (also referred to as “Angler”) hereby agree to be bound by and comply with all Tournament Rules, the Code of Conduct, payment schedules and all other guidelines and regulations in the 2020 Bassmaster Opens rules or otherwise communicated to me in writing by B.A.S.S. I also certify that I am a member in good standing with B.A.S.S., I am physically fit and that there are no health-related reasons or problems which preclude my participation in the tournament series. P2. RELEASE OF LIABILITY; INDEMNIFICATION 2.1. I expressly assume all risks associated with my participation in the tournament series and for myself, my executors, administrators, heirs, next of kin, successors and assigns, I hereby waive, release and discharge B.A.S.S., LLC, its affiliates and subsidiaries, the hosts, sponsors and tournament series officials (“Released Parties”) from any and all losses, liabilities, claims, damages and expenses (including without limitation, attorneys fees and related costs), of any kind (hereinafter “Claims”) arising out of or in connection with my participation in the tournament series, including but not limited to Claims involving, death, disability, personal injury and/or property damage. -

Angler Flirts with World Bass Record

ADVENTURE Fly-fishing on the Guadalupe * March 24, 2006 Texas’ Premier Outdoor Newspaper Volume 2, Issue 15 * See Page 19 www.lonestaroutdoornews.com INSIDE FISHING Angler flirts with world bass record By Darlene McCormick Escondido, Calif., March 20 when he If the catch meets International Sanchez landed what could be the world-record Game Fish Association requirements, largemouth bass. Weakley’s fish would break the 74-year- The fish weighed in at 25.1 pounds old record. The reigning record large- California’s Mac Weakley and his on a hand-held Berkley digital scale, mouth bass, weighing 22 pounds, 4 longtime fishing buddies ended their said Weakley, 32, of Carlsbad, Calif., in ounces, was caught in 1932 by George quest for fishing’s Holy Grail on a rainy a phone interview. Perry at Georgia’s Montgomery Lake. Monday morning with a white rat- “We’ve been after that fish and two But there’s a catch to this fish story: A lack of a true winter has the tlesnake jig. other fish for years. It’s crazy. It’s been a Weakley foul-hooked the bass behind notoriously picky walleye biting Weakley was bed-fishing near the wild day — a really, really, wild day,” he 25-1 POUNDS: Mike Winn holds the fish Mac early this year at Lake Meredith. handicapped pier at Dixon Lake in said. See Record, Page 10 Weakley caught. Photo by Mac Weakley. Even so, lake guides say the fish are still fussy about what they go after. See Page 8 Think you’ve caught a record- breaking fish but all you’ve got to weigh it on is a hand-held scale. -

This Is Bass

THISTHIS ISIS BASSBASS THIS IS BASS Providing quality multimedia entertainment to avid outdoor consumers. • Part of the ESPN family since 2001, BASS is a multimedia company that is the definitive authority on the sport of bass fishing. • 40 years strong, BASS is the industry leader and the brand bass fishing fans look to for the latest tips, techniques and tournament news. • BASS is a lifestyle brand that is comprised of: - A membership organization - A tournament sports league - Multi-media platforms. Television Internet Publications 2 MEMBERSHIP ORGANIZATION • BASS offers a Membership Program that is currently over 500,00 members strong. - Anglers who join BASS can take advantage of exclusive member benefits. In addition to receiving 11 issues of Bassmaster magazine, members receive tournament eligibility, decals and patches for their boats and jerseys, opportunities to access extended content via our BASS Insider membership, boat theft insurance policy, hotel and car rental discounts and chances to win free products each month. • Included in the 500,000+ member base are about 21,000 BASS Federation Nation Club members – the most active group of BASS members. - Responsible for donating over 28,000 volunteer hours to help with conservation projects. - Support approximately 1,500 youth events reaching over 150,000 children each year. • BASS Life Members consist of 60,000 avid anglers. Life member benefits include an endless subscription of Bassmaster and BASS Times as well as special benefits such as access to the Life Member Lounge, a gift bag and special seating credentials each year at the Bassmaster Classic. 3 TOURNAMENT SPORTS LEAGUE Recognizing the spirit of competition, BASS provides tournament platforms for anglers at all skill levels.