Roger L'estrange and the Huguenots: Continental Protestantism and the Church of England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rıchard Hooker: an Introductıon to Hıs Lıfe and Thought Torrance KIRBY

İslâmÎ İlİmler derGİsİ, yıl 11 cİlt 11 sayı 2 Güz 2016 (69/81) rıchard hOOker: an ıntrOductıOn tO hıs lıfe and thOuGht Torrance KIRBY, McGill University, Montreal, Canada Abstract Richard Hooker (1554-1600) Richard Hooker was born in Devon, near Exeter in April 1554; he died at Bishopsbourne, Kent on 2 November 1600. From 1579 to 1585 he was a Fellow of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, and read the Hebrew Lecture at the University during this period. In 1585 Queen Elizabeth I appointed him Master of the Temple Church at the Inns of Court where he engaged in a preaching struggle with his assistant, Walter Travers. Their disagreement over the theological and political assumptions of the reformed Church of England as defined by the Act of Uniformity of 1559 and the Book of Common Prayer led to Hooker’s composition of his great work Of the Lawes of Ecclesiasticall Politie (1593). The treatise consists of a lengthy preface which frames the polemical context, fol- lowed by eight books. The first four books address what he terms “gen- eral meditations”: (1) the nature of law in general, (2) the proper uses of the authorities of reason and revelation, (3) the application of the latter to the government of the church and (4) objections to practices inconsistent with the continental “reformed” example. The final four address the more “particular decisions” of the Church’s constitution: (5) public religious duties as prescribed by the Book of Common Prayer (1559), (6) the power of ecclesiastical jurisdiction, (7) the authority of bishops and (8) the supreme authority of the Prince in both church and commonwealth, and hence their unity in the Christian state. -

Nicolas Lamoignon De Basville, Intendant Du Languedoc De 1685 À 1718 : Une Longévité Rare

Académie des Sciences et Lettres de Montpellier 1 Séance du 16 novembre 2020 Nicolas Lamoignon de Basville, intendant du Languedoc de 1685 à 1718 : une longévité rare Valdo PELLEGRIN Maître de conférences honoraire à l’Université de Montpellier MOTS-CLÉS : Lamoignon de Basville, intendant, Montpellier, Louis XIV, monuments, dragonnades, camisards, Brousson. RÉSUMÉ : L’intendant Nicolas Lamoignon de Basville (1648-1724) réside à Montpellier de 1685 à 1718 dans l’hôtel d’Audessan. Après une description de cet hôtel nous évoquons la jeunesse, les études de Basville, son mariage et ses amitiés parisiennes, puis ses débuts comme avocat au parlement de Paris et sa nomination comme intendant du Poitou. En 1685, il est nommé par le roi intendant du Languedoc à la suite d’Henri d’Aguesseau qui refuse de dragonner les protestants nombreux dans la province. Le roi lui confie comme mission prioritaire d’éradiquer le protestantisme en Languedoc. Basville aura à gérer le difficile conflit de la guerre des camisards et un débarquement anglais à Sète, en 1710. Sur le plan de l’urbanisme et de l’architecture, il supervise la construction de la porte du Peyrou et l’installation de la statue équestre de Louis XIV quelques semaines avant son départ à la retraite en 1718. Mais jusqu’au bout, Basville n’a rien perdu de sa combativité contre les protestants. C’est lui qui a inspiré en 1724, année de sa mort, l’édit de Louis XV redoublant de sévérité vis-à-vis des protestants. L’histoire retiendra surtout la lutte implacable de Basville vis-à-vis des protestants du Languedoc. -

The Theology of the French Reformed Churches Martin I

The Theology of the French Reformed Churches REFORMED HISTORICAL-THEOLOGICAL STUDIES General Editors Joel R. Beeke and Jay T. Collier BOOKS IN SERIES: The Christology of John Owen Richard W. Daniels The Covenant Theology of Caspar Olevianus Lyle D. Bierma John Diodati’s Doctrine of Holy Scripture Andrea Ferrari Caspar Olevian and the Substance of the Covenant R. Scott Clark Introduction to Reformed Scholasticism Willem J. van Asselt, et al. The Spiritual Brotherhood Paul R. Schaefer Jr. Teaching Predestination David H. Kranendonk The Marrow Controversy and Seceder Tradition William VanDoodewaard Unity and Continuity in Covenantal Thought Andrew A. Woolsey The Theology of the French Reformed Churches Martin I. Klauber The Theology of the French Reformed Churches: From Henri IV to the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes Edited by Martin I. Klauber Reformation Heritage Books Grand Rapids, Michigan The Theology of the French Reformed Churches © 2014 by Martin I. Klauber All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any man ner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Direct your requests to the publisher at the following address: Reformation Heritage Books 2965 Leonard St. NE Grand Rapids, MI 49525 6169770889 / Fax 6162853246 [email protected] www.heritagebooks.org Printed in the United States of America 14 15 16 17 18 19/10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 [CIP info] For additional Reformed literature, request a free book list from Reformation Heritage Books at the above regular or e-mail address. -

From Oppression to Freedom

FROM OPPRESSION TO FREEDOM John Jay and his Huguenot Heritage The Protestant Reformation changed European history, when it challenged the Roman Catholic Church in the 16th century. John Calvin was a French theologian who led his own branch of the movement. French Protestants were called Huguenots as a derisive Conflict Over the term by Catholics. Protestant Disagreements escalated into a series of religious wars Reformation in seventeenth-century France. Tens of thousands of Huguenots were killed. Finally, the Edict of Nantes was issued in 1598 to end the bloodshed; it established Catholicism as the official religion of France, but granted Protestants the right to worship in their own way. Eighty-seven years later, in 1685, King Louis XIV issued the Edict of Fontainebleau, which reversed the Edict of Nantes, and declared the public practice of Protestantism illegal. Louis regarded religious pluralism as an obstacle to his achieving complete power over the French people. By his order, Huguenot churches were demolished, Huguenot schools were The Revocation of closed, all newborns were required to be baptized as Roman Catholics, and it became illegal for the the Edict of Nantes Protestant laity to emigrate or remove their valuables from France. A View of La Rochelle In La Rochelle, a busy seaport on France’s Atlantic coast, the large population of Huguenot merchants, traders, and artisans there suffered the persecution that followed the edict. Among them was Pierre Jay, an affluent trader, and his family. Pierre’s church was torn down. In order to intimidate him into converting to Catholicism, the government quartered unruly soldiers called dragonnades in his house, to live with him and his family. -

Introduction

Introduction The Other Voice [Monsieur de Voysenon] told [the soldiers] that in the past he had known me to be a good Catholic, but that he could not say whether or not I had remained that way. At that mo- ment arrived an honorable woman who asked them what they wanted to do with me; they told her, “By God, she is a Huguenot who ought to be drowned.” Charlotte Arbaleste Duplessis-Mornay, Memoirs The judge was talking about the people who had been ar- rested and the sorts of disguises they had used. All of this terrified me. But my fear was far greater when both the priest and the judge turned to me and said, “Here is a little rascal who could easily be a Huguenot.” I was very upset to see myself addressed that way. However, I responded with as much firmness as I could, “I can assure you, sir, that I am as much a Catholic as I am a boy.” Anne Marguerite Petit Du Noyer, Memoirs The cover of this book depicting Protestantism as a woman attacked on all sides reproduces the engraving that appears on the frontispiece of the first volume of Élie Benoist’s History of the Edict of Nantes.1 This illustration serves well Benoist’s purpose in writing his massive work, which was to protest both the injustice of revoking an “irrevocable” edict and the oppressive measures accompanying it. It also says much about the Huguenot experience in general, and the experience of Huguenot women in particular. When Benoist undertook the writing of his work, the association between Protestantism and women was not new. -

The Reception of Hobbes's Leviathan

This is a repository copy of The reception of Hobbes's Leviathan. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/71534/ Version: Published Version Book Section: Parkin, Jon (2007) The reception of Hobbes's Leviathan. In: Springborg, Patricia, (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Hobbes's Leviathan. The Cambridge Companions to Philosophy, Religion and Culture . Cambridge University Press , Cambridge , pp. 441-459. https://doi.org/10.1017/CCOL0521836670.020 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ jon parkin 19 The Reception of Hobbes’s Leviathan The traditional story about the reception of Leviathan was that it was a book that was rejected rather than read seriously.1 Leviathan’s perverse amalgamation of controversial doctrine, so the story goes, earned it universal condemnation. Hobbes was outed as an athe- ist and discredited almost as soon as the work appeared. Subsequent criticism was seen to be the idle pursuit of a discredited text, an exer- cise upon which young militant churchmen could cut their teeth, as William Warburton observed in the eighteenth century.2 We need to be aware, however, that this was a story that was largely the cre- ation of Hobbes’s intellectual opponents, writers with an interest in sidelining Leviathan from the mainstream of the history of ideas. -

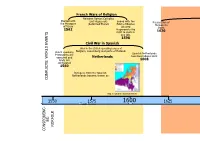

Refugee Timeline for Workshop

French Wars of Religion Between Roman Catholics Started with and Huguenots Ended with the the Massacre Persecution of (Reformed French Edict of Nantes Huguenots of Vassy Allowed starts 1562 Hugeneouts the 1620 right to work in any job. 1598 Civil War in Spanish War in the Dutch speaking areas of Belgium, Luxemburg and parts of Holland. Dutch speaking Spanish Netherlands Protestants are becomes independent executed and Netherlands lands are 1608 confiscated 1560 Refugees from the Spanish Netherlands became known as CONFLICTS: WORLD EVENTS Map showing the Spanish Nether- 1550 1575 1600 1625 Tudor Period ES: NORFOLK CONSEQUENC- French Persecution of Huguenots (Reformed French Protestants) The Dragonnades King Louis XIV of France encouraged soldiers to abuse French Protestants and destroy or steal their possessions. He wanted Huguenot families to leave France or convert to Catholicism. Edict of Fontainebleau Louis IX of France reversed the Edict of Nantes which stopped religious freedom for Protestants. 1685 King Louis XIV France French Flag before the French Revolution 1650 1675 170 1725 1750 1775 Stuart Period Russian persecution Ends with the Edict of of Jews Versailles which The Italian Wars of allowed non-Catholics to practice their Started with the May Laws. religion and marry Independence 1882 without becoming Jews forced to Catholic Individual states become live in certain 1787 independent from Austria and unite areas and not allowed in specific schools French Revolution or to do specific jobs. Public rebelled against the king and religious leaders. Resulted in getting rid of the King 1789-99 French Flag after the French Revolution Individual states which form 1775 1800 1825 1850 1875 1900 Georgian Period Victorian Period Russian persecution Second World War Congolese Wars Syrian Civil Global war involved the vast Repeal of the May Conflict involving nine African War majority of the world's nations. -

The Historic Episcopate

THE HISTORIC EPISCOPATE By ROBERT ELLIS THOMPSON, M.A., S.T. D., LL.D. of THE PRESBYTERY of PHILADELPHIA PHILADELPHIA tEfce Wtstminmx pre** 1910 "3^70 Copyright, 1910, by The Trustees of The Presbyterian Board of Publication and Sabbath School Work Published May, 1910 <§;G!.A265282 IN ACCORDANCE WITH ACADEMIC USAGE THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO THE PRESIDENT, FACULTY AND TRUSTEES OF MUHLENBERG COLLEGE IN GRATEFUL RECOGNITION OF HONORS CONFERRED PREFACE The subject of this book has engaged its author's attention at intervals for nearly half a century. The present time seems propitious for publishing it, in the hope of an irenic rather than a polemic effect. Our Lord seems to be pressing on the minds of his people the duty of reconciliation with each other as brethren, and to be bringing about a harmony of feeling and of action, which is beyond our hopes. He is beating down high pretensions and sectarian prejudices, which have stood in the way of Christian reunion. It is in the belief that the claims made for what is called "the Historic Episcopate" have been, as Dr. Liddon admits, a chief obstacle to Christian unity, that I have undertaken to present the results of a long study of its history, in the hope that this will promote, not dissension, but harmony. If in any place I have spoken in what seems a polemic tone, let this be set down to the stress of discussion, and not to any lack of charity or respect for what was for centuries the church of my fathers, as it still is that of most of my kindred. -

Inventing a French Tyrant: Crisis, Propaganda, and the Origins of Fénelon’S Ideal King

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository INVENTING A FRENCH TYRANT: CRISIS, PROPAGANDA, AND THE ORIGINS OF FÉNELON’S IDEAL KING Kirsten L. Cooper A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2013 Approved by: Jay M. Smith Chad Bryant Lloyd S. Kramer © 2013 Kirsten L. Cooper ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kirsten L. Cooper: Inventing a French Tyrant: Crisis, Propaganda, and the Origins of Fénelon’s Ideal King (Under the direction of Jay M. Smith and Chad Bryant) In the final decades of the seventeenth century, many voices across Europe vehemently criticized Louis XIV, the most well-known coming from the pen of François Fénelon from within Versailles itself. There were, however, many other critics of varied backgrounds who participated in this common discourse of opposition. From the 1660s to the 1690s the authors of these pamphlets developed a stock of critiques of Louis XIV that eventually coalesced into a negative depiction of his entire style of government. His manner of ruling was rejected as monstrous and tyrannical. Fénelon's ideal king, a benevolent patriarch that he presents as an alternative to Louis XIV, was constructed in opposition to the image of Louis XIV developed and disseminated by these international authors. In this paper I show how all of these authors engaged in a process of borrowing, recopying, and repackaging to create a common critical discourse that had wide distribution, an extensive, transnational audience, and lasting impact for the development of changing ideals of sovereignty. -

Les Mots Et Les Choses: the Obscenity of Pierre Bayle

Les mots et les choses: the obscenity of Pierre Bayle van der Lugt, Mara Date of deposit 12/02/2019 Document version Author’s accepted manuscript Access rights © Modern Humanities Research Association 2018. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. This is the author created, accepted version manuscript following peer review and may differ slightly from the final published version. Citation for van der Lugt, M. (2018). Les mots et les choses: the obscenity of published version Pierre Bayle. Modern Language Review, 113(4), 714-741 Link to published https://doi.org/10.5699/modelangrevi.113.4.0714 version Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: https://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ LES MOTS ET LES CHOSES : THE OBSCENITY OF PIERRE BAYLE ‘Pourquoi se gêner dans un Ouvrage que l'on ne destine point aux mots, mais aux choses…?’ - Pierre Bayle, Éclaircissement sur les Obscénités. Why bother with words in a work devoted to things? asks Pierre Bayle, early modern philosopher and troublemaker extraordinaire. That is: why should the author of an historical-critical dictionary, which deals with things and acts and events, with the content of words rather than with words themselves, concern himself with such a trivial matter as the politeness of style?1 This question, of the relationship between words and things, and the responsibilities of authors using words to describe things, is at the centre of Bayle’s curious semi-provocative semi-apologetic essay or Éclaircissement sur les Obscénités. It is also part of an age-old argument attributed to the Cynics and sometimes the Stoics, which would become a locus communis for early modern discussions of obscenity. -

An Efficient System of Espionage Which, A

ORGANIZA TION OF THE REFORMED CHURCH 27 an efficient system of espionage which, a decade later, smashed the Cinq-Mars conspiracy and incidentally gave Sedan to France; by the creation of provincial intendants in 1637 with overriding financial, judicial and police powers, and responsible to the king and his chief minister alone; and by a steady process of attrition, aided by the sale of offices, which gradually transformed the feudal aristocracy into a noblesse de cour lacking real influence and dependent on the monarchy for continued favours.2 In foreign policy, Richelieu turned the Thirty Years' War into a contest between Bourbon and Hapsburg, and with Protestant help gave France a new Rhine frontier. In the struggle with Spain, the king’s chief officer of state was able to secure the Pyrenees border and gain a foothold in northern Italy.3 This was Mazarin’s inheritance after Richelieu's death in 1642. On the European front, with the aid of the young Conde against the Spaniards at Rocroi and with that of the Protestant Turenne in Germany, he gained for France a leading place in Europe in the years following the Peace of Westphalia in 1648. The war with Spain continued until the Peace of the Pyrenees in 1659, after France, with Cromwell’s support, had successfully invaded the Spanish Netherlands. At this treaty, the Pyrenean border was finally determined and the province of Artois ceded by Spain, thus providing the French with an additional barrier to foreign incursions in the vulnerable north-east.4 At home, Mazarin’s pressing need to finance an aggressive foreign policy sparked off the series of civil wars from 1648 until 1652 known collectively as the Fronde. -

A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (M-S)

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2009-05-01 A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (M-S) Gary P. Gillum [email protected] Susan Wheelwright O'Connor Alexa Hysi Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Gillum, Gary P.; O'Connor, Susan Wheelwright; and Hysi, Alexa, "A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (M-S)" (2009). Faculty Publications. 11. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/11 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 1462 MACHIAVELLI, NICCOLÒ, 1469-1527 Rare 854.318 N416e 1675 The Works of the famous Nicolas Machiavel: citizen and Secretary of Florence. Written Originally in Italian, and from thence newly and faithfully Translated into English London: Printed for J.S., 1675. Description: [24], 529 [21]p. ; 32 cm. References: Wing M128. Subjects: Political science. Political ethics. War. Florence (Italy)--History. Added Author: Neville, Henry, 1620-1694, tr. Contents: -The History of florence.-The Prince.-The original of the Guelf and Ghibilin Factions.-The life of Castruccio Castracani.-The Murther of Vitelli, &c. by Duke Valentino.-The State of France.- The State of Germany.-The Marriage of Belphegor, a Novel.-Nicholas Machiavel's Letter in Vindication of Himself and His Writings. Notes: Printer's device on title-page. Title enclosed within double line rule border. Head pieces. Translated into English by Henry Neville.