Identification of Sterile, Noninvasive Cultivars of Japanese Spirea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ontogenetic Studies on the Determination of the Apical Meristem In

Ontogenetic studies on the determination of the apical meristem in racemose inflorescences D i s s e r t a t i o n Zur Erlangung des Grades Doktor der Naturwissenschaften Am Fachbereich Biologie Der Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz Kester Bull-Hereñu geb. am 19.07.1979 in Santiago Mainz, 2010 CONTENTS SUMMARY OF THE THESIS............................................................................................ 1 ZUSAMMENFASSUNG.................................................................................................. 2 1 GENERAL INTRODUCTION......................................................................................... 3 1.1 Historical treatment of the terminal flower production in inflorescences....... 3 1.2 Structural understanding of the TF................................................................... 4 1.3 Parallel evolution of the character states referring the TF............................... 5 1.4 Matter of the thesis.......................................................................................... 6 2 DEVELOPMENTAL CONDITIONS FOR TERMINAL FLOWER PRODUCTION IN APIOID UMBELLETS...................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Introduction...................................................................................................... 7 2.2 Materials and Methods..................................................................................... 9 2.2.1 Plant material.................................................................................... -

Illustration Sources

APPENDIX ONE ILLUSTRATION SOURCES REF. CODE ABR Abrams, L. 1923–1960. Illustrated flora of the Pacific states. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA. ADD Addisonia. 1916–1964. New York Botanical Garden, New York. Reprinted with permission from Addisonia, vol. 18, plate 579, Copyright © 1933, The New York Botanical Garden. ANDAnderson, E. and Woodson, R.E. 1935. The species of Tradescantia indigenous to the United States. Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. Reprinted with permission of the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University. ANN Hollingworth A. 2005. Original illustrations. Published herein by the Botanical Research Institute of Texas, Fort Worth. Artist: Anne Hollingworth. ANO Anonymous. 1821. Medical botany. E. Cox and Sons, London. ARM Annual Rep. Missouri Bot. Gard. 1889–1912. Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis. BA1 Bailey, L.H. 1914–1917. The standard cyclopedia of horticulture. The Macmillan Company, New York. BA2 Bailey, L.H. and Bailey, E.Z. 1976. Hortus third: A concise dictionary of plants cultivated in the United States and Canada. Revised and expanded by the staff of the Liberty Hyde Bailey Hortorium. Cornell University. Macmillan Publishing Company, New York. Reprinted with permission from William Crepet and the L.H. Bailey Hortorium. Cornell University. BA3 Bailey, L.H. 1900–1902. Cyclopedia of American horticulture. Macmillan Publishing Company, New York. BB2 Britton, N.L. and Brown, A. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British posses- sions. Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York. BEA Beal, E.O. and Thieret, J.W. 1986. Aquatic and wetland plants of Kentucky. Kentucky Nature Preserves Commission, Frankfort. Reprinted with permission of Kentucky State Nature Preserves Commission. -

Virginia Spiraea Recovery Plan

VIRGINIA SPIRAEA (Spiraea virginiana Britton) Recovery Plan U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region Five Virginia Spiraea (Spiraea virginiana Britton) Recovery Plan Prepared by: Douglas W. Ogle Associate Professor of Biology Virginia Highlands Community College Abingdon, VA 24210 for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region Five One Gateway Center Newton Corner, MA 02158 APPROVED: Drez{or,2 egion Five DATE: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY VIRGINIA SPIRAEA RECOVERY PLAN Current Status: Virginia spiraea (Spiraea virginiana) consists of 31 stream populations in seven states from West Virginia and Ohio to Georgia, down from 39 populations in eight states. The plant is threatened by small population size, a paucity of sexual reproduction and dispersal, and manipulation of riverine habitat. The species was listed as threatened on June 15, 1990. Habitat Requirements: S. virginiana typically is found in disturbed sites along rivers and streams. The species requires disturbance sufficient to inhibit arboreal competition, yet without scour that will remove most organic material or clones. Recovery Objective: To delist the species. Recovery Criteria: Delisting will be considered when: (1) three stable populations are permanently protected in each drainage where populations are currently known, (2) stable populations are established on protected sites in each drainage where documented vouchers have been collected, (3) potential habitat in the states with present or past collections has been searched for additional populations, and (4) representatives of each genotype are cultivated in a permanent collection. Recovery Strategy: Protect the known populations and their habitat, and restore rangewide distribution. Understand the environmental tolerances and genetic diversity of the species to ensure long-term reproductive viability. -

(GISD) 2021. Species Profile Spiraea Japonica. Available

FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Spiraea japonica Spiraea japonica System: Terrestrial Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Plantae Magnoliophyta Magnoliopsida Rosales Rosaceae Common name Japanese meadowsweet (English), Japanese spiraea (English) Synonym Spiraea bumalda , Burv. Spiraea japonica , var. alpina Maxim. Similar species Spiraea viginiana, Spiraea betulifolia Summary Spiraea japonica is a deciduous, perennial shrub native to Asia that has been introduced to the United States as an ornamental. It aggressively invades disturbed areas and forms dense stands that outcompete native species. Spiraea japonica is found growing along streams, rivers, forest edges, roadsides and fields. It often spreads locally when its hardy seeds are transported along watercourses and in fill dirt. view this species on IUCN Red List Species Description S. japonica is a deciduous shrub that grows 1.2m to almost 2m in height and about the same in width. It has slender erect stems that are brown to reddish-brown, round in cross-section and sometimes hairy. The leaves are generally an ovate shape about 2.5cm to 7.5cm long, have toothed margins, and alternate along the stem. The seeds measure about 2.5mm in length and are found in small lustrous capsules (Remaley, 1998). Clusters of rosy-pink flowers are found at the tips of the branches (flowers are white to rosy-pink for natural populations native to Asia). S. japonica is naturally variable in form and there are many varieties of it in the horticulture trade. (Nine varieties have been described within the species so far, and southwest China is the center for biodiversity of the species (Zhang et al. -

Spiraea Japonica USDA Plants Code

NEW YORK NON -NATIVE PLANT INVASIVENESS RANKING FORM Scientific name: Spiraea japonica USDA Plants Code: SPJA Common names: Japanese spiraea Native distribution: Eastern Asia Date assessed: April 3, 2009; edited May 15, 2009 Assessors: Steve Glenn, Gerry Moore Reviewers: LIISMA SRC Date Approved: April 29, 2009 Form version date: 3 March 2009 New York Invasiveness Rank: Moderate (Relative Maximum Score 50.00-69.99) Distribution and Invasiveness Rank ( Obtain from PRISM invasiveness ranking form ) PRISM Status of this species in each PRISM: Current Distribution Invasiveness Rank 1 Adirondack Park Invasive Program Not Assessed Not Assessed 2 Capital/Mohawk Not Assessed Not Assessed 3 Catskill Regional Invasive Species Partnership Not Assessed Not Assessed 4 Finger Lakes Not Assessed Not Assessed 5 Long Island Invasive Species Management Area Not Present Insignificant 6 Lower Hudson Not Assessed Not Assessed 7 Saint Lawrence/Eastern Lake Ontario Not Assessed Not Assessed 8 Western New York Not Assessed Not Assessed Invasiveness Ranking Summary Total (Total Answered*) Total (see details under appropriate sub-section) Possible 1 Ecological impact 40 ( 20 ) 6 2 Biological characteristic and dispersal ability 25 (22 ) 17 3 Ecological amplitude and distribution 25 ( 25 ) 21 4 Difficulty of control 10 ( 10 ) 4 Outcome score 100 ( 77 )b 48a † Relative maximum score 62.34 § New York Invasiveness Rank Moderate (Relative Maximum Score 50.00-69.99) * For questions answered “unknown” do not include point value in “Total Answered Points Possible.” If “Total Answered Points Possible” is less than 70.00 points, then the overall invasive rank should be listed as “Unknown.” †Calculated as 100(a/b) to two decimal places. -

Population Genetics and Breeding Ecology of the Rare Clonal Shrub, Spiraea Virginiana (Rosaceae)

Population Genetics and Breeding Ecology of the Rare Clonal Shrub, Spiraea virginiana (Rosaceae) A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Department of Biological Sciences of the College of Arts and Sciences by Jessica R. Brzyski M.S. Biology Georgia Southern University, December 2006 Committee Chair: T. M. Culley, Ph.D. i ABSTRACT Two of the most prevalent reasons cited for the decrease in species abundance are the loss and modification of habitat and the impact from invasive species. Riparian species face both of these challenges, being in a habitat that experiences abundant water flow modifications and experiencing a degree of disturbance which is often desired by invasive species. As a result, riparian habitat contains high levels of biodiversity, and also a high frequency of rare species. Therefore, the goal of my research was to identify genetic and reproductive factors that may be hindering population growth of rare riparian species. Spiraea virginiana can be classified as a characteristic riparian shrub, is considered rare throughout its natural range, and it is suggested to be negatively impacted by competition with the invasive S. japonica. Using this study species, I examined the extent of both clonal growth and sexual reproduction, and seed germination potential using field and laboratory methods. Genetic analyses show that S. virginiana is highly clonal and populations are isolated from one another. Genetic data also indicate that S. virginiana is likely to have been rare for an extended time period rather than recently so. -

Vascular Plant Inventory

VASCULAR PLANT INVENTORY AND PLANT COMMUNITY CLASSIFICATION FOR CARL SANDBURG HOME NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE Report for the Vertebrate and Vascular Plant Inventories: Appalachian Highlands and Cumberland/Piedmont Networks Prepared by NatureServe for the National Park Service Southeast Regional Office February 2003 NatureServe is a non-profit organization providing the scientific knowledge that forms the basis for effective conservation action. A NatureServe Technical Report Prepared for the National Park Service under Cooperative Agreement H 5028 01 0435. Citation: White, Jr., Rickie D. 2003. Vascular Plant Inventory and Plant Community Classification for Carl Sandburg Home National Historic Site. NatureServe: Durham, North Carolina. © 2003 NatureServe NatureServe 6114 Fayetteville Road, Suite 109 Durham, NC 27713 919-484-7857 International Headquarters 1101 Wilson Boulevard, 15th Floor Arlington, Virginia 22209 www.natureserve.org National Park Service Southeast Regional Office Atlanta Federal Center 1924 Building 100 Alabama St., S.W. Atlanta, GA 30303 404-562-3163 The view and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not consitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. This report consists of the main report along with a series of appendices with information about the plants and plant communities found at the site. Electronic files have been provided to the National Park Service in addition to hard copies. Current information on all communities described here can be found on NatureServe Explorer at www.natureserve.org/explorer. Cover photo: Close-up of a flower of the pink lady’s slipper (Cypripedium acaule) in an oak-hickory forest at Carl Sandburg Home National Historic Site. -

Diversity and Evolution of Rosids

Diversity and Evolution of Rosids . roses, currants, peonies . Eudicots • continue survey through the eudicots or tricolpates • vast majority of eudicots are Rosids (polypetalous) and Asterids core (sympetalous) eudicots rosid asterid Eudicots • unlike Asterids, Rosids (in orange) now represent a diverse set of families *Saxifragales • before examining the large Rosid group, look at a small but important order of flowering plants - Saxifragales Paeonia Sedum *Saxifragales • small group of 16 families and about 2500 species sister to Rosids • ancient lineage from 120 mya and underwent rapid radiation Paeonia Sedum *Saxifragales • part of this ancient radiation may involve this small family of holo-parasites - Cynomoriaceae *Saxifragales • they generally can be identified by their two or more separate or semi-fused carpels, but otherwise quite variable Paeonia Sedum Paeoniaceae 1 genus / 33 species • like many of these families, Paeonia exhibits an Arcto-Tertiary distribution Paeoniaceae 1 genus / 33 species • small shrubs with primitive features of perianth and stamens • hypogynous with 5-8 separate carpels developing into follicles Cercidiphyllaceae 1 genus / 2 species • small trees (kadsura-tree) restricted to eastern China and Japan . • . but fossils in North America and Europe from Tertiary Cercidiphyllaceae 1 genus / 2 species • unisexual, wind-pollinated but do produce follicles Hamamelidaceae 27 genera and 80 species - witch hazels • family of trees and shrubs in subtropical and temperate areas but only 1 species in Wisconsin - witch -

Species of Conservation Concern Process) Wayne National Forest 13700 US Highway 33 Nelsonville, OH 45764

United States Department of Agriculture At-Risk Species Draft Assessment Supplemental Report Wayne National Forest Forest Wayne National Forest Plan Service Forest Revision June 2019 Prepared By: Richard Gardner Patrick Mercer (Federally Listed Plants & Plant Species of (Federally Listed Wildlife) Conservation Concern Process) OWayne National Forest Ohio Department of Natural Resources 13700 US Highway 33 2045 Morse Road Nelsonville, OH 45764 Columbus, OH 43229 Forest Service (Wildlife Species of Conservation Concern Process) Wayne National Forest 13700 US Highway 33 Nelsonville, OH 45764 Responsible Official: Forest Supervisor Carrie Gilbert Cover Photo: The federally endangered running buffalo clover Trifolium( stoloniferum). USDA photo by Kyle Brooks The use of trade or firm names in this publication is for reader information and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture of any product or service. In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. -

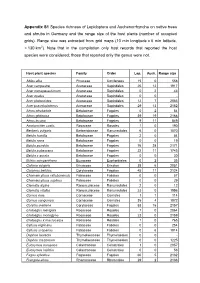

Appendix S1 Species Richness of Lepidoptera and Auchenorrhyncha on Native Trees and Shrubs in Germany and the Range Size of the Host Plants (Number of Occupied Grids)

Appendix S1 Species richness of Lepidoptera and Auchenorrhyncha on native trees and shrubs in Germany and the range size of the host plants (number of occupied grids). Range size was extracted from grid maps (10 min longitude x 6 min latitude, ≈ 130 km 2). Note that in the compilation only host records that reported the host species were considered; those that reported only the genus were not. Host plant species Family Order Lep. Auch. Range size Abies alba Pinaceae Coniferales 15 0 558 Acer campestre Aceraceae Sapindales 25 12 1917 Acer monspessulanum Aceraceae Sapindales 0 2 43 Acer opalus Aceraceae Sapindales 0 0 - Acer platanoides Aceraceae Sapindales 12 7 2083 Acer pseudoplatanus Aceraceae Sapindales 29 13 2152 Alnus alnobetula Betulaceae Fagales 0 2 54 Alnus glutinosa Betulaceae Fagales 39 19 2168 Alnus incana Betulaceae Fagales 9 11 849 Amelanchier ovalis Rosaceae Rosales 1 0 190 Berberis vulgaris Berberidaceae Ranunculales 6 0 1070 Betula humilis Betulaceae Fagales 2 0 54 Betula nana Betulaceae Fagales 0 0 19 Betula pendula Betulaceae Fagales 76 28 2171 Betula pubescens Betulaceae Fagales 22 11 1745 Betula x aurata Betulaceae Fagales 0 0 30 Buxus sempervirens Buxaceae Euphorbiales 0 2 35 Calluna vulgaris Ericaceae Ericales 38 6 2051 Carpinus betulus Corylaceae Fagales 45 11 2124 Chamaecytisus ratisbonensis Fabaceae Fabales 0 0 57 Chamaecytisus supinus Fabaceae Fabales 0 0 29 Clematis alpina Ranunculaceae Ranunculales 2 0 12 Clematis vitalba Ranunculaceae Ranunculales 23 0 1556 Cornus mas Cornaceae Cornales 1 1 114 Cornus sanguinea -

Evolution of Rosaceae Fruit Types Based on Nuclear Phylogeny in The

Evolution of Rosaceae Fruit Types Based on Nuclear Phylogeny in the Context of Geological Times and Genome Duplication Yezi Xiang,1,† Chien-Hsun Huang,1,† Yi Hu,2 Jun Wen,3 Shisheng Li,4 Tingshuang Yi,5 Hongyi Chen,4 Jun Xiang,*,4 and Hong Ma*,1 1State Key Laboratory of Genetic Engineering and Collaborative Innovation Center of Genetics and Development, Ministry of Education Key Laboratory of Biodiversity and Ecological Engineering, Institute of Plant Biology, Center of Evolutionary Biology, School of Life Sciences, Fudan University, Shanghai, China 2Department of Biology, the Huck Institutes of Life Sciences, the Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 3The Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 4Hubei Collaborative Innovation Center for the Characteristic Resources Exploitation of Dabie Mountains, Hubei Key Laboratory of Economic Forest Germplasm Improvement and Resources Comprehensive Utilization, School of Life Sciences, Huanggang Normal College,Huanggang,Hubei,China 5Plant Germplasm and Genomics Center, Germplasm Bank of Wild Species, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, China †These authors contributed equally to this work. *Corresponding authors: E-mails: [email protected]; [email protected] Associate editor: Hongzhi Kong Abstract Fruits are the defining feature of angiosperms, likely have contributed to angiosperm successes by protecting and dis- persing seeds, and provide foods to humans and other animals, with many morphological types and important ecological and agricultural implications. Rosaceae is a family with 3000 species and an extraordinary spectrum of distinct fruits, including fleshy peach, apple, and strawberry prized by their consumers, as well as dry achenetum and follicetum with features facilitating seed dispersal, excellent for studying fruit evolution. -

Insular Ecosystems of the Southeastern United States: a Regional Synthesis to Support Biodiversity Conservation in a Changing Climate

U.S. Department of the Interior Southeast Climate Science Center Insular Ecosystems of the Southeastern United States: A Regional Synthesis to Support Biodiversity Conservation in a Changing Climate Professional Paper 1828 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover photographs, left column, top to bottom: Photographs are by Alan M. Cressler, U.S. Geological Survey, unless noted otherwise. Ambystoma maculatum (spotted salamander) in a Carolina bay on the eastern shore of Maryland. Photograph by Joel Snodgrass, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. Geum radiatum, Roan Mountain, Pisgah National Forest, Mitchell County, North Carolina. Dalea gattingeri, Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park, Catoosa County, Georgia. Round Bald, Pisgah and Cherokee National Forests, Mitchell County, North Carolina, and Carter County, Tennessee. Cover photographs, right column, top to bottom: Habitat monitoring at Leatherwood Ford cobble bar, Big South Fork Cumberland River, Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area, Tennessee. Photograph by Nora Murdock, National Park Service. Soil island, Davidson-Arabia Mountain Nature Preserve, Dekalb County, Georgia. Photograph by Alan M. Cressler, U.S. Geological Survey. Antioch Bay, Hoke County, North Carolina. Photograph by Lisa Kelly, University of North Carolina at Pembroke. Insular Ecosystems of the Southeastern United States: A Regional Synthesis to Support Biodiversity Conservation in a Changing Climate By Jennifer M. Cartwright and William J. Wolfe U.S. Department of the Interior Southeast Climate Science Center Professional Paper 1828 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Director U.S.