DRAFT Strategy Paper Protection Interventions in Response to Internal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Splintered Warfare Alliances, Affiliations, and Agendas of Armed Factions and Politico- Military Groups in the Central African Republic

2. FPRC Nourredine Adam 3. MPC 1. RPRC Mahamat al-Khatim Zakaria Damane 4. MPC-Siriri 18. UPC Michel Djotodia Mahamat Abdel Karim Ali Darassa 5. MLCJ 17. FDPC Toumou Deya Gilbert Abdoulaye Miskine 6. Séléka Rénovée 16. RJ (splintered) Mohamed Moussa Dhaffane Bertrand Belanga 7. Muslim self- defense groups 15. RJ Armel Sayo 8. MRDP Séraphin Komeya 14. FCCPD John Tshibangu François Bozizé 9. Anti-Balaka local groups 13. LRA 10. Anti-Balaka Joseph Kony 12. 3R 11. Anti-Balaka Patrice-Edouard Abass Sidiki Maxime Mokom Ngaïssona Splintered warfare Alliances, affiliations, and agendas of armed factions and politico- military groups in the Central African Republic August 2017 By Nathalia Dukhan Edited by Jacinth Planer Abbreviations, full names, and top leaders of armed groups in the current conflict Group’s acronym Full name Main leaders 1 RPRC Rassemblement Patriotique pour le Renouveau de la Zakaria Damane Centrafrique 2 FPRC Front Populaire pour la Renaissance de la Centrafrique Nourredine Adam 3 MPC Mouvement Patriotique Centrafricain Mahamat al-Khatim 4 MPC-Siriri Mouvement Patriotique Centrafricain (Siriri = Peace) Mahamat Abdel Karim 5 MLCJ Mouvement des Libérateurs Centrafricains pour la Justice Toumou Deya Gilbert 6 Séleka Rénovée Séléka Rénovée Mohamed Moussa Dhaffane 7 Muslim self- Muslim self-defense groups - Bangui (multiple leaders) defense groups 8 MRDP Mouvement de Résistance pour la Défense de la Patrie Séraphin Komeya 9 Anti-Balaka local Anti-Balaka Local Groups (multiple leaders) groups 10 Anti-Balaka Coordination nationale -

Operations • Repatriation Movements

Update on Key Events in the Central African Republic From 10 to 26 February 2020 Operations • Repatriation movements UNHCR CAR has resumed its activities of voluntary repatriation of Central African refugees from the various countries of asylum. It is hosting a convoy of 250 people from the Lolo camp in Cameroon, today, 26 February 2020. Voluntary repatriation of Central African refugees from Cameroon UNHCR Also the last week, a convoy of 94 households including 151 returnees was welcomed at Bangui airport from Brazzaville. All these people received, after their arrival, monetary assistance and certificates of loss of documents for adults. UNHCR is also continuing preparations for the resumption of voluntary repatriation of refugees from the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Cameroon. • Fire alerts in this dry season are becoming more and more recurrent at the various IDP sites, particularly in Kaga Bandoro, Batangafo and Bambari. These fires are sometimes due to poor handling of household fires. To minimize the risk of fire, UNHCR is currently conducting awareness campaigns at IDP sites. This awareness raising focused on the different mechanisms for fire management and strengthening the fire prevention strategy. In response, UNHCR provided assistance in complete NFI kits to 26 fire-affected households at the Bambari livestock site. Kaga-Bandero : le 16 /02/ 2020 au site de lazare, l’incendie provoqué par le feu de cuisson. 199 huttes et des biens appartenant aux Personnes déplacées ont été consumés. Photo UNHCR • M'boki and Zemio: UNHCR, in partnership with the National Commission for Refugees (NRC), organized a verification and registration operation for refugees residing in Haut- Mbomou. -

Emergency Telecommunications Cluster

Central African Republic - Conflict ETC Situation Report #13 Reporting period 01/08/2016 to 31/01/2017 These Situation Reports will now be distributed every two months. The next report will be issued on or around 31/03/17. Highlights • The Emergency Telecommunications Cluster (ETC) continues to provide vital security telecommunications and data services to the humanitarian community in 8x operational areas across Central African Republic (C.A.R.): Bangui, Bambari, Kaga- Bandoro, Bossangoa, Zemio, N'Dele, Paoua and Bouar. • A new ETC Coordinator joined the operation in mid-January 2017. • The ETC has requested US$885,765 to carry out its activities to support humanitarian responders until the end of June 2017. • The ETC is planning for the transition of long-term shared Information and Communications Technology (ICT) services from the end of June this year. Fred, ETC focal point in Bambari, checking the telecommunications equipment. Situation Overview Photo credit: ETC CAR The complex humanitarian and protection crisis affecting Central African Republic since 2012 shows no sign of abating. The country continues to suffer from instability and an estimated 2.2 million people will be in need of humanitarian assistance in 2017, including 1.1 million children. By the end of 2016, an estimated 420,000 people were internally displaced due to the ongoing conflict, with an additional 453,000 having sought refuge in neighbouring countries. Page 1 of 6 The ETC is a global network of organizations that work together to provide shared communications services in humanitarian emergencies Response The ETC is providing shared internet connectivity services and security telecommunications to the response community in 8x sites across the country: Kaga-Bandoro and Bossangoa, managed by United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF); Zemio, managed by United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR); N'Dele, managed by UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA); and Bambari, Bangui, Bouar and Paoua, managed by the World Food Programme (WFP). -

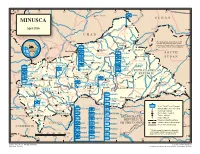

MINUSCA T a Ou M L B U a a O L H R a R S H Birao E a L April 2016 R B Al Fifi 'A 10 H R 10 ° a a ° B B C H a VAKAGA R I CHAD

14° 16° 18° 20° 22° 24° 26° ZAMBIA Am Timan é Aoukal SUDAN MINUSCA t a ou m l B u a a O l h a r r S h Birao e a l April 2016 r B Al Fifi 'A 10 h r 10 ° a a ° B b C h a VAKAGA r i CHAD Sarh Garba The boundaries and names shown ouk ahr A Ouanda and the designations used on this B Djallé map do not imply official endorsement Doba HQ Sector Center or acceptance by the United Nations. CENTRAL AFRICAN Sam Ouandja Ndélé K REPUBLIC Maïkouma PAKISTAN o t t SOUTH BAMINGUI HQ Sector East o BANGORAN 8 BANGLADESH Kaouadja 8° ° SUDAN Goré i MOROCCO u a g n i n i Kabo n BANGLADESH i V i u HAUTE-KOTTO b b g BENIN i Markounda i Bamingui n r r i Sector G Batangafo G PAKISTAN m Paoua a CAMBODIA HQ Sector West B EAST CAMEROON Kaga Bandoro Yangalia RWANDA CENTRAL AFRICAN BANGLADESH m a NANA Mbrès h OUAKA REPUBLIC OUHAM u GRÉBIZI HAUT- O ka Bria Yalinga Bossangoa o NIGER -PENDÉ a k MBOMOU Bouca u n Dékoa MAURITANIA i O h Bozoum C FPU CAMEROON 1 OUHAM Ippy i 6 BURUNDI Sector r Djéma 6 ° a ° Bambari b ra Bouar CENTER M Ouar Baoro Sector Sibut Baboua Grimari Bakouma NANA-MAMBÉRÉ KÉMO- BASSE MBOMOU M WEST Obo a Yaloke KOTTO m Bossembélé GRIBINGUI M b angúi bo er ub FPU BURUNDI 1 mo e OMBELLA-MPOKOYaloke Zémio u O Rafaï Boali Kouango Carnot L Bangassou o FPU BURUNDI 2 MAMBÉRÉ b a y -KADEI CONGO e Bangui Boda FPU CAMEROON 2 Berberati Ouango JTB Joint Task Force Bangui LOBAYE i Gamboula FORCE HQ FPU CONGO Miltary Observer Position 4 Kade HQ EGYPT 4° ° Mbaïki Uele National Capital SANGHA Bondo Mongoumba JTB INDONESIA FPU MAURITANIA Préfecture Capital Yokadouma Tomori Nola Town, Village DEMOCRATICDEMOCRATIC Major Airport MBAÉRÉ UNPOL PAKISTAN PSU RWANDA REPUBLICREPUBLIC International Boundary Salo i Titule g Undetermined Boundary* CONGO n EGYPT PERU OFOF THE THE CONGO CONGO a FPU RWANDA 1 a Préfecture Boundary h b g CAMEROON U Buta n GABON SENEGAL a gala FPU RWANDA 2 S n o M * Final boundary between the Republic RWANDA SERBIA Bumba of the Sudan and the Republic of South 0 50 100 150 200 250 km FPU SENEGAL Sudan has not yet been determined. -

Security Sector Reform in the Central African Republic

Security Sector Reform in the Central African Republic: Challenges and Priorities High-level dialogue on building support for key SSR priorities in the Central African Republic, 21-22 June 2016 Cover Photo: High-level dialogue on SSR in the CAR at the United Nations headquarters on 21 June 2016. Panellists in the center of the photograph from left to right: Adedeji Ebo, Chief, SSRU/OROLSI/DPKO; Jean Willybiro-Sako, Special Minister-Counsellor to the President of the Central African Republic for DDR/SSR and National Reconciliation; Miroslav Lajčák, Minister of Foreign and European Affairs of the Slovak Republic; Joseph Yakété, Minister of Defence of Central African Republic; Mr. Parfait Onanga-Anyanga, Special Representative of the Secretary-General for the Central African Republic and Head of MINUSCA. Photo: Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs of the Slovak Republic The report was produced by the Security Sector Reform Unit, Office of Rule of Law and Security Institutions, Department of Peacekeeping Operations, United Nations. © United Nations Security Sector Reform Unit, 2016 Map of the Central African Republic 14° 16° 18° 20° 22° 24° 26° AmAm Timan Timan The boundaries and names shown and the designations é oukal used on this map do not implay official endorsement or CENTRAL AFRICAN A acceptance by the United Nations. t a SUDAN lou REPUBLIC m u B a a l O h a r r S h Birao e a l r B Al Fifi 'A 10 10 h r ° a a ° B b C h a VAKAGA r i CHAD Sarh k Garba Sarh Bahr Aou CENTRAL Ouanda AFRICAN Djallé REPUBLIC Doba BAMINGUI-BANGORAN Sam -

Central African Republic: Population Displacement January 2012

Central African Republic: Population Displacement January 2012 94,386 internally displaced persons (IDPs) in 5,652 the Central African Republic (CAR), where close SUDAN 24,951 65,364 Central to 21,500 were newly displaced in 2012 1,429 African refugees 71,601 returnees from within CAR or Birao neighboring countries 12,820 CHAD 6,880 6,516 Vakaga 19,867 refugees from Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo and 225 11,967 asylum-seekers of varying nationalities reside in Ouanda- the CAR and 152,861 Central African refugees 12,428 Djallé Ndélé are living in neighboring countries 3,827 543 Bamingui- 85,092 Central 7,500 Bangoran African refugees 8,736 1,500 2,525 Kabo 812 Ouadda 5,208 SOUTH SUDAN Markounda Bamingui Haute-Kotto Ngaoundaye 500 3,300 Batangafo Kaga- Haut- Paoua Bandoro Mbomou Nana- Nana-Gribizi Koui Boguila 20 6,736 Bria Bocaranga Ouham Ouham Ouaka 5,517 Djéma 1,033 Central 2,3181,964 5,615 African refugees 3,000 Pendé 3,287 2,074 1,507 128 Bossemtélé Kémo Bambari 1,226 Mbomou 800 Baboua Obo Zémio Ombella M'Poko 1,674 Rafaï Nana-Mambéré 5,564 Bakouma Bambouti CAMEROON 6,978 Basse- Bangassou Kotto Mambéré-Kadéï Bangui Lobaye Returnees Mongoumba Internally displaced persons (IDPs) 1,372 Central Refugees Sangha- African refugees Figures by sub-prefecture Mbaéré Returnee DEMOCRATIC movement REPUBLIC OF THE IDP camp IDP CONGO CONGO Refugee camp Refugee 0 50 100 km Sources: Various sources compiled by OCHA CAR Due to diculty in tracking spontaneous returns, breakdown of refugee returnees and IDP returnees is not available at the sub-prefectural level. -

Security Council Distr.: General 15 October 2018

United Nations S/2018/922* Security Council Distr.: General 15 October 2018 Original: English Situation in the Central African Republic Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. In its resolution 2387 (2017), the Security Council extended the mandate of the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) until 15 November 2018 and requested that I report on its implementation. The present report is submitted pursuant to that resolution. 2. Further to my initiative to reform peacekeeping and my Action for Peacekeeping initiative, I asked Juan Gabriel Valdés to lead an independent strategic review of MINUSCA. He undertook that review from June until September 2018, with 15 multidisciplinary experts from various agencies in the United Nations System, and visited the Central African Republic from 2 to 15 July. He consulted with a wide range of stakeholders, including President Faustin-Archange Touadéra, Prime Minister Simplice Sarandji and members of his Government, representatives of the National Assembly and main political parties, armed groups, civil society, women and youth groups, religious leaders and the Central African population, as well as memb ers of the diplomatic community, including the African Union, the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), the European Union, MINUSCA and the United Nations country and humanitarian teams. In addition to Bangui, the team visited Bambari, Bangassou, Bouar, Bria and Kaga Bandoro, and sought consultations in Addis -

Central African Republic Report of the Secretary-Gen

United Nations S/2020/545 Security Council Distr.: General 16 June 2020 Original: English Central African Republic Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. By its resolution 2499 (2019), the Security Council extended the mandate of the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) until 15 November 2020 and requested me to report on its implementation every four months. The present report provides an update on major developments in the Central African Republic since the previous report of 14 February 2020 (S/2020/124), including the impact of the outbreak of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19), which was officially declared in the Central African Republic on 14 March. II. Political situation Political developments 2. The political environment was marked by increased mobilization ahead of the presidential and legislative elections scheduled for December 2020, contributing to tensions between political stakeholders. The Special Representative of the Secretary- General for the Central African Republic and Head of MINUSCA, Mankeur Ndiaye, with his good offices and political facilitation mandate, engaged with national stakeholders and international partners to encourage constructive and inclusive political dialogue to preserve fragile gains. 3. On 11 February, 14 opposition parties formed the Coalition de l’opposition démocratique with the proclaimed objective of ensuring free, fair, inclusive and timely elections. The coalition includes the parties Union pour le renouveau centrafricain of the former Prime Minister, Anicet-Georges Dologuélé; the Kwa Na Kwa of the former President, François Bozizé; the Convention républicaine pour le progrès social of the former Prime Minister, Nicolas Tiangaye; the Chemin de l’espérance of the former President of the National Assembly, Karim Meckassoua; and the Be Africa Ti E Kwe of the former Prime Minister, Mahamat Kamoun. -

Assessment of Conflict Dynamics in Mercy Corps' Area of Intervention

Assessment of Conflict Dynamics in Mercy Corps’ Area of Intervention (Nana-Mambéré Prefecture) Thierry Vircoulon Independent consultant, Research Associate to the French Institute for International Affairs and Professor at the university of Sciences- Po (Paris) August 2017 Table of contents List of Acronyms ....................................................................................................................... 3 1) Introduction and Acknowledgements ................................................................................ 4 2) Executive Summary .......................................................................................................... 5 3) List of Recommendations .................................................................................................. 8 4) Understanding the local context ........................................................................................ 9 5) Conflict Analysis of the Bouar Region ............................................................................. 14 6) Consequences of the conflict .......................................................................................... 25 7) Recommendations .......................................................................................................... 33 8) Annexes .......................................................................................................................... 36 Mission schedule ................................................................................................. -

Central African Republic Situation Update WFP Response in Numbers

Central African Republic Situation Update CHAD The security situation in Bangui has calmed down on Wednesday and residents were slowly reappearing on the streets. Some shops, restaurants and markets have also reopened. A UN Map goes here curfew is in place in Bangui from 9.00 to 16.00. The situation has remained calmed this morning. In Bossangoa, the tension has eased since the Situation Report #19 13 December 2013 December 13 #19 Report Situation French troops arrived and began disarming armed groups. Area of clashes In Bouar, there are persistent rumours of an attack by the anti-Balaka group, tensions remain high. Central African Republic WFP Response Food Assistance Since 08 December, WFP has distributed 325 metric tons of food to 68,389 people in Bangui. As of 12 December, about 13,000 people have been assisted In numbers in Bossangoa. Central African Republic Republic African Central On 12 December, WFP assisted a total of 19,303 beneficiaries with 107 metric tons of food 127,000 people displaced in Bangui nationwide. In Bangui, WFP distributed emergency food rations to 8,000 IDPs in St Charles (38 mt), (OCHA, 11 December) 4,000 people in the PK5 neighbourhood (19 mt) and 533,000 people displaced in CAR food for hot meals to feed 410 orphans at Voix du Coeur (ongoing). In Bossangoa, 1,840 people were (OCHA, 09 December) assisted with 27 mt of food at Le Eveché and 1,217 people with 18 mt of food at Libertè. Emergency school feeding is being carried out in the Before the outbreak of violence on Bouar area and 3,836 children were assisted with 05 December: 10 mt of food. -

OCHA CAR DRAFT Snapshot

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC Overview of incidents affecting humanitarian workers April 2021 CONTEXT Incidents from A decline in security incidents affecting humanitarian organizations was recorded in April 1 January to 30 April 2021 (34 incidents against 53 recorded in March). However, the civilian population remains the first victim of the renewed tensions and violence observed in several prefectures since the end of 2020. 202 BiBiraorao 124 The prefectures of Nana-Gribizi (7 incidents), Ouham (6 incidents), and Bamingui-Bamoran (5 incidents) were the most affected this month. Ndélé Theft, robbery, looting, threats, and assaults accounted for half of the incidents (16 out of 11 34), while the other half were interferences and restrictions. Markounda Bamingui Kabo Bamingui2 31 5 Kaga-Kaga- 2 Batangafo Bandoro 9 humanitarians were injured in April 2021. Paoua Batangafo Bandoro 2 7 6 1 2850 1 BriaBria Bocaranga 5Mbrès Djéma . 3 Bakala Ippy 38 2 Bossangoa Bouca 7 BBozoumozoum Bouca 1 3 2 Dekoa 1 BabouaBouar 21 28 4 DEATH INJURED Bouar 11 INCIDENTS 2 Bossangoa Sibut Grimari Bambari 42 2 Bambari BakoumaBakouma Bogangolo 3 32 Zémio Obo Bambouti 1 21 5 Zemio 5 Bossembélé 1 Ndjoukou 7 2 1 1 Damara Kouango 4 5 Carnot Boali 7 1612 Amada-Gaza 2 Carnot 1 2 Gambo 2 1 1 Bimbo 2 61,4% 1 2 Bangassou 202 1 11 1 1 Boda Mbaiki Mobaye Jan - Apr 2021 Jan - Apr 2021 Jan - Apr 2021 2 Kembe 1 Mongoumba X # OF NCIDENTS Satema Alindao 0 1 - 2 Bangui PERCENTAGE OF INCIDENTS BY TYPE NUMBER OF INCIDENTS Bangui 3- 4 16 5 - 9 Murder (1) Hostilities (2) Kaga-Bandoro 28 -

OCHA Graphics Style Book (Pdf)

Contents Design • Paper Dimensions • Landscape Orientation • Margins and Columns • Other Page Elements • Fonts • Colours • OCHA logo Representing Data • Tables • Bar Charts • Line Charts • Pie Charts • Surface-Area Charts • Matrices Representing Geography • Elements of a Map Style COUNTRY • A4 Basemaps • Example Map Styles R • Effective Use of Shaded Relief iv e OCEAN r • World Thematic Mapping • Chlorapleth Mapping Capital 250 km Photography • Placement • Quality • News Value and Timeliness • Copyright • Metadata OCHA Graphics Style Book - October 2011 1 Introduction Purpose Designing good infographics The Graphics Style Book is for OCHA staff A good infographic can be hard to design as it who focus on information management (IM) and requires gathering lots of information to create an geographic information systems (GIS). appealing graphic. Here are some tips on how to design a good infographic: It will help IM/GIS officers improve the quality of their information products and deliver consistent 1. Define key messages visual design across OCHA. The book explains best practices in design and describes different ways to Your visual products need to tell a story. Consider represent information. the audience and determine the purpose of the product. Is it for planning, advocacy or analysis? Templates and styles used in this book are available on OCHAnet, under the “Communications 2. Collect data and Public Advocacy” section: http://ochanet. Collect information that will allow you to portray unocha.org/CA/Advocacy/ key messages, convey facts and grab users’ attention. For additional information, please contact: 3. Sketch the information United Nations Office for the Coordination of Hu- Draw a sketch on paper using pencils; plan the manitarian Affairs space for text, charts, pictures, etc.