Take My Breath Away Transformations in the Practices of Relatedness and Intimacy Through Australia’S 2019–2020 Convergent Crises

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Helena Mace Song List 2010S Adam Lambert – Mad World Adele – Don't You Remember Adele – Hiding My Heart Away Adele

Helena Mace Song List 2010s Adam Lambert – Mad World Adele – Don’t You Remember Adele – Hiding My Heart Away Adele – One And Only Adele – Set Fire To The Rain Adele- Skyfall Adele – Someone Like You Birdy – Skinny Love Bradley Cooper and Lady Gaga - Shallow Bruno Mars – Marry You Bruno Mars – Just The Way You Are Caro Emerald – That Man Charlene Soraia – Wherever You Will Go Christina Perri – Jar Of Hearts David Guetta – Titanium - acoustic version The Chicks – Travelling Soldier Emeli Sande – Next To Me Emeli Sande – Read All About It Part 3 Ella Henderson – Ghost Ella Henderson - Yours Gabrielle Aplin – The Power Of Love Idina Menzel - Let It Go Imelda May – Big Bad Handsome Man Imelda May – Tainted Love James Blunt – Goodbye My Lover John Legend – All Of Me Katy Perry – Firework Lady Gaga – Born This Way – acoustic version Lady Gaga – Edge of Glory – acoustic version Lily Allen – Somewhere Only We Know Paloma Faith – Never Tear Us Apart Paloma Faith – Upside Down Pink - Try Rihanna – Only Girl In The World Sam Smith – Stay With Me Sia – California Dreamin’ (Mamas and Papas) 2000s Alicia Keys – Empire State Of Mind Alexandra Burke - Hallelujah Adele – Make You Feel My Love Amy Winehouse – Love Is A Losing Game Amy Winehouse – Valerie Amy Winehouse – Will You Love Me Tomorrow Amy Winehouse – Back To Black Amy Winehouse – You Know I’m No Good Coldplay – Fix You Coldplay - Yellow Daughtry/Gaga – Poker Face Diana Krall – Just The Way You Are Diana Krall – Fly Me To The Moon Diana Krall – Cry Me A River DJ Sammy – Heaven – slow version Duffy -

GIORGIO MORODER Album Announcement Press Release April

GIORGIO MORODER TO RELEASE BRAND NEW STUDIO ALBUM DÉJÀ VU JUNE 16TH ON RCA RECORDS ! TITLE TRACK “DÉJÀ VU FEAT. SIA” AVAILABLE TODAY, APRIL 17 CLICK HERE TO LISTEN TO “DÉJÀ VU FEATURING SIA” DÉJÀ VU ALBUM PRE-ORDER NOW LIVE (New York- April 17, 2015) Giorgio Moroder, the founder of disco and electronic music trailblazer, will be releasing his first solo album in over 30 years entitled DÉJÀ VU on June 16th on RCA Records. The title track “Déjà vu featuring Sia” is available everywhere today. Click here to listen now! Fans who pre-order the album will receive “Déjà vu feat. Sia” instantly, as well as previously released singles “74 is the New 24” and “Right Here, Right Now featuring Kylie Minogue” instantly. (Click hyperlinks to listen/ watch videos). Album preorder available now at iTunes and Amazon. Giorgio’s long-awaited album DÉJÀ VU features a superstar line up of collaborators including Britney Spears, Sia, Charli XCX, Kylie Minogue, Mikky Ekko, Foxes, Kelis, Marlene, and Matthew Koma. Find below a complete album track listing. Comments Giorgio Moroder: "So excited to release my first album in 30 years; it took quite some time. Who would have known adding the ‘click’ to the 24 track would spawn a musical revolution and inspire generations. As I sit back readily approaching my 75th birthday, I wouldn’t change it for the world. I'm incredibly happy that I got to work with so many great and talented artists on this new record. This is dance music, it’s disco, it’s electronic, it’s here for you. -

October 2018 Supplementary Piano Solos

OCTOBER 2018 SACRED PIANO JAZZ An Impressionist-Style Service Essential Solos Series Piano Methods Alfred’s Basic Adult Piano Course: Popular Hits, Level 2 Arr. Tom Gerou Favorite popular hits correlated page-by-page with Alfred’s Basic Adult Piano Course and Alfred’s Basic Adult All-in- One Course. Titles: As Time Goes By (from Casablanca) • City of Stars (from La La Land) • Fever (Peggy Lee) • Firework (Katy Perry) • Happy Together (The Turtles) • Havana (Camila Cabello) • Sorry (Justin Bieber) • You’ll Be Back (from the Broadway musical Hamilton) • and more. 00-44698 | Level 2 | $9.99 UPC: 038081508146 | ISBN-13: 978-1-4706-2734-8 Alfred’s Basic Adult Piano Course: Popular Hits, Level 1 Arr. Tom Gerou Titles: Don’t Stop Believin’ (Journey) • James Bond Theme • Let It Go (from Walt Disney’s Frozen) • The Rose (Bette Midler) • Star Wars® (Main Theme) • Take My Breath Away (Berlin) • Try to Remember (from The Fantasticks) • You Raise Me Up (Josh Groban) • and many more. 00-44697 | Level 1 | $9.50 UPC: 038081508139 | ISBN-13: 978-1-4706-2733-1 Fall Stock Order Season Order $1,500 by December 7, 2018 to receive: Maximum stock order discount 90 days dating Ordering online? Use promo code FALL18. * Offer valid for one qualifying Alfred Music Stock Order ($1,500 net minimum). Price and availability subject to change without notice. Maximum discount restrictions apply to select titles and product lines. Additional restrictions may apply. Contact your Account Rep for more information. Order today! (800) 292-6122 | [email protected] | alfred.com Page 4 – this will be a full page ad for Lang Lang. -

![[ KARAOKE - 70-80'S by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 476 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0158/karaoke-70-80s-by-artist-no-of-tunes-476-450158.webp)

[ KARAOKE - 70-80'S by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 476 ]

[ KARAOKE - 70-80'S by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 476 ] 10CC >> I'M NOT IN LOVE {K} 10CC >> RUBBER BULLETS {K} 1927 >> IF I COULD {K} ABBA >> DANCING QUEEN {K} ABBA >> FERNANDO {K} ABBA >> GIMME GIMME GIMME {K} ABBA >> HONEY HONEY {K} ABBA >> I DO I DO I DO I DO I DO {K} ABBA >> MAMMA MIA {K} ABBA >> MONEY MONEY MONEY {K} ABBA >> RING RING {K} ABBA >> S O S {K} ABBA >> WATERLOO {K} AC DC >> BACK IN BLACK {K} AC DC >> DIRTY DEEDS DONE DIRT CHEAP {K} AC DC >> HIGHWAY TO HELL {K} AC DC >> IT'S A LONG WAY TO THE TOP {K} AC DC >> JAILBREAK {K} AC DC >> ROCK N ROLL AIN'T NOISE POLLUTION {K} AC DC >> T N T {K} AC DC >> WHO MADE WHO {K} AC DC >> YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT LONG {K} ADAM ANT >> ANT MUSIC {K} AEROSMITH >> DUDE ( LOOKS LIKE A LADY ) {K} AIR SUPPLY >> ALL OUT OF LOVE {K} ALICE COOPER >> DEPARTMENT OF YOUTH {K} ALICE COOPER >> SCHOOL'S OUT {K} ALTERED IMAGES >> HAPPY BIRTHDAY {K} ALVIN STARDUST >> MY COO CA CHOO {K} AMERICA >> SISTER GOLDEN HAIR {K} AMII STEWART >> KNOCK ON WOOD {K} ANGELS >> AM I EVER GOING TO SEE YOUR FACE AGAIN {K} ANGELS >> NO SECRETS {K} AUSTRALIAN CRAWL >> BOYS LIGHT UP {K} AUSTRALIAN CRAWL >> ERROL {K} B J THOMAS >> RAINDROPS KEEP FALLIN' ON MY HEAD {K} B52'S >> LOVE SHACK {K} B52'S >> PRIVATE IDAHO {K} B52'S >> ROAM {K} B52'S >> ROCK LOBSTER {K} BACHMAN TURNER OVERDRIVE >> TAKIN' CARE OF BUISINESS {K} BACHMAN TURNER OVERDRIVE >> YOU AIN'T SEEN NOTHING YET {K} BANANARAMA >> I WANT YOU BACK {K} BARRY BLUE >> DANCING ON A SATURDAY NIGHT {K} BARRY WHITE >> CAN'T GET ENOUGH OF YOUR LOVE BABY {K} BARRY WHITE >> YOU'RE THE -

Members Only 2016 List with Logo-Top 40

song list Artist Song A-Ha Take on Me Ace of Base The Sign Adele Rolling In The Deep Aerosmith I Don't Want To Miss A Thing B.O.B. Beautiful Girls Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) Bangles Eternal Flame Belinda Carlisle Heaven is a Place on Earth Berlin take my breath away Beyonce Single Ladies Billy Idol Dancin’ with Myself Bon Jovi You Give Love a Bad Name Bon jovi Livin’ on a Prayer Britney Spears Toxic Bruno Mars Treasure Bruno Mars Uptown Funk Bryan Adams Summer of 69 Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe Cee-lo Green Forget You Cher Turn Back Time Chrissie Hynde Stand By You Cutting Crew I Just Died in Your Arms Tonight Cyndi Lauper Time after Time Cyndi Lauper Girls just wanna have fun Cyndi Lauper Girls Just Want to Have Fun Daft Punk Get Lucky Def Leppard Photograph Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar on Me DNCE Cake By The Ocean Duran Duran Hungry like the Wolf Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud Eddie Money Take Me Home Tonight Elvis Presley Can't Help Falling in Love Eric Clapton Wonderful Tonight Frank Sinatra The Way You Look Tonight Gnarls Barkley Crazy Guns + Roses Sweet Child of Mine !8 Hall+ Oates You Make My Dreams Hall+ oates Maneater Huey Lewis + The News Power Of Love Human League Don't You Want Me Irene Cara What a Feelin' J. Geils Band Centerfold Joan Jett I Love Rock + Roll John Legend All Of Me Journey Any Way You Want It Journey Don’t Stop Believing Justin Timberlake Can't Stop the Feeling Justin Timberlake Suit & Tie Katrina + the Waves Walking on Sunshine Katy Perry California Gurls Katy Perry Teenage Dream Ke$ha Tik Tok Kenny Loggins Footloose kim wilde Keep me hanging on Kim Wilde Kids in America Lady Antebellum Need You Now Lady Gaga Just Dance Loverboy Workin For the Weekend Madonna Medley (Vogue, Borderline, Holiday, Lucky Star, Get into the Groove) Maroon 5 Sugar Maroon 5 Sunday Morning Marvin Gaye Let's Get it On Meghan Trainor All About that Bass Michael Buble Everything Michael Buble Save The Last Dance For Me Michael Jackson Billie Jean Michael Jackson P.Y.T. -

Top500 Final

1. MICHAEL JACKSON Billie Jean 2. EAGLES Hotel California 3. BON JOVI Livin’ On A Prayer 4. ROLLING STONES Satisfaction 5. POLICE Every Breath You Take 6. ARETHA FRANKIN Respect 7. JOURNEY Don’t Stop Believin’ 8. BEATLES Hey Jude 9. GUESS WHO American Woman 10. QUEEN Bohemian Rhapsody 11. MARVIN GAYE I Heard It Through The Grapevine 12. JOAN JETT I Love Rock And Roll 13. BEE GEES Night Fever 14. BEACH BOYS Good Vibrations 15. BLONDIE Call Me 16. FOUR SEASONS December 1963 (Oh, What A Night) 17. BRYAN ADAMS Summer Of 69 18. SURVIVOR Eye Of The Tiger 19. LED ZEPPELIN Stairway To Heaven 20. ROY ORBISON Pretty Woman 21. OLIVIA NEWTON JOHN Physical 22. B.T.O. Takin’ Care Of Business 23. NEIL DIAMOND Sweet Caroline 24. DON McLEAN American Pie 25. TOM COCHRANE Life Is A Highway 26. BOSTON More Than A Feeling 27. MICHAEL JACKSON Rock With You 28. ROD STEWART Maggie May 29. VAN HALEN Jump 30. ELTON JOHN/ KIKI DEE Don’t Go Breaking My Heart 31. FOUR SEASONS Big Girls Don’t Cry 32. FLEETWOOD MAC Dreams 33. FIFTH DIMENSION Aquarius/Let The Sunshine In 34. HALL AND OATES Maneater 35. NEIL YOUNG Heart Of Gold 36. PRINCE When Doves Cry 37. EAGLES Lyin’ Eyes 38. ARCHIES Sugar, Sugar 39. THE KNACK My Sharona 40. BEE GEES Stayin’ Alive 41. BOB DYLAN Like A Rolling Stone 42. AMERICA Sister Golden Hair 43. ALANNAH MYLES Black Velvet 44. FRANKI VALLI Grease 45. PAT BENATAR Hit Me With Your Best Shot 46. EMOTIONS Best Of My Love 47. -

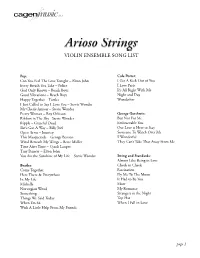

Violin Ensemble Song List

VIOLIN ENSEMBLE SONG LIST Pop: Cole Porter: Can You Feel The Love Tonight – Elton John I Get A Kick Out of You Every Breath You Take – Police I Love Paris God Only Knows – Beach Boys It’s All Right With Me Good Vibrations – Beach Boys Night and Day Happy Together – Turtles Wunderbar I Just Called to Say I Love You – Stevie Wonder My Cherie Amour – Stevie Wonder Pretty Woman – Roy Orbison George Gershwin: Ribbon in The Sky –Stevie Wonder But Not For Me Ripple – Grateful Dead Embraceable You She’s Got A Way – Billy Joel Our Love is Here to Stay Open Arms – Journey Someone To Watch Over Me This Masquerade – George Benson S’Wonderful Wind Beneath My Wings – Bette Midler They Can’t Take That Away From Me Time After Time – Cyndi Lauper Tiny Dancer – Elton John You Are the Sunshine of My Life – Stevie Wonder Swing and Standards: Almost Like Being in Love Beatles: Cheek to Cheek Come Together Fascination Here There & Everywhere Fly Me To The Moon In My Life It Had to Be You Michelle More Norwegian Wood My Romance Something Strangers in the Night Things We Said Today Top Hat When I’m 64 When I Fall in Love With A Little Help From My Friends page 1 Broadway & Hollywood: International Classics: All I Ask of You (Phantom of the Opera) Al Di La Anything Goes Amour Around the World in 80 Days Arrivederchi Roma As Time Goes By (Casablanca) Autumn Leaves Days of Wine & Roses Besame Mucho Edelweiss (The Sound of Music) Black Orpheus Can You Read My Mind (Superman) Danny Boy 42nd Street Girl from Ipanema I Could Have Danced All Night (My Fair Lady) La Vie En Rose I’ll Take Romance (Rogers & Hammerstein) Meditation I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face (My Fair Lady) My Wild Irish Rose Lara’s Theme (Dr. -

Music List by Year

Song Title Artist Dance Step Year Approved 1,000 Lights Javier Colon Beach Shag/Swing 2012 10,000 Hours Dan + Shay & Justin Bieber Foxtrot Boxstep 2019 10,000 Hours Dan and Shay with Justin Bieber Fox Trot 2020 100% Real Love Crystal Waters Cha Cha 1994 2 Legit 2 Quit MC Hammer Cha Cha /Foxtrot 1992 50 Ways to Say Goodbye Train Background 2012 7 Years Luke Graham Refreshments 2016 80's Mercedes Maren Morris Foxtrot Boxstep 2017 A Holly Jolly Christmas Alan Jackson Shag/Swing 2005 A Public Affair Jessica Simpson Cha Cha/Foxtrot 2006 A Sky Full of Stars Coldplay Foxtrot 2015 A Thousand Miles Vanessa Carlton Slow Foxtrot/Cha Cha 2002 A Year Without Rain Selena Gomez Swing/Shag 2011 Aaron’s Party Aaron Carter Slow Foxtrot 2000 Ace In The Hole George Strait Line Dance 1994 Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus Foxtrot/Line Dance 1992 Ain’t Never Gonna Give You Up Paula Abdul Cha Cha 1996 Alibis Tracy Lawrence Waltz 1995 Alien Clones Brothers Band Cha Cha 2008 All 4 Love Color Me Badd Foxtrot/Cha Cha 1991 All About Soul Billy Joel Foxtrot/Cha Cha 1993 All for Love Byran Adams/Rod Stewart/Sting Slow/Listening 1993 All For One High School Musical 2 Cha Cha/Foxtrot 2007 All For You Sister Hazel Foxtrot 1991 All I Know Drake and Josh Listening 2008 All I Want Toad the Wet Sprocket Cha Cha /Foxtrot 1992 All I Want (Country) Tim McGraw Shag/Swing Line Dance 1995 All I Want For Christmas Mariah Carey Fast Swing 2010 All I Want for Christmas is You Mariah Carey Shag/Swing 2005 All I Want for Christmas is You Justin Bieber/Mariah Carey Beach Shag/Swing 2012 -

Retro-80S-Hits.Pdf

This document will assist you with the right choices of music for your retro event; it contains examples of songs used during an 80’s party. Song Artist Greece 2000 18 If I Could 1927 That's When I Think Of You 1927 I Ran A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing ( If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls Take On Me A Ha Poison Arrow ABC The Look Of Love ABC When Smokey Sings ABC Who Made Who AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC Stand & Deliver Adam & The? Ant Music Adam Ant Goody Two Shoes Adam Ant Classic Adrian Gurvitz Janie's Got A Gun Aerosmith Rag Doll Aerosmith Manhattan Skyline A-Ha Take On Me A-Ha Love Is Alannah Myles Poison Alice Cooper Love Resurrection Alison Moyet Don't Talk To Me About Love Altered Images Take It Easy Andy Taylor Japanese Boy Aneka Obession Animotion Election Day Arcadia Sugar Sugar Archies 0402 277 208 | [email protected] | www.djdiggler.com.au | 21 Higgs Ct, Wynnum West, Queensland, Australia 4178 Downhearted Australian Crawl Errol Australian Crawl Reckless Australian Crawl Shutdown Australian Crawl Things Don't Seem Australian Crawl Love Shack B52's Roam B52's Strobelight B52's Tarzan Boy Baltimora I Want You Back Bananarama Venus Bananarama Heaven Is A Place On Earth Belinda Carlisle Mad About You Belinda Carlisle Imagination Belouis Some Sex I'm A Berlin Take My Breath Away Berlin Key Largo Bertie Higgins In A Big Country Big Country Look Away Big Country Hungry Town Big Pig Lovely Day Bill Withers Dancing With Myself Billy Idol Flesh For Fantasy Billy Idol Hot In The City Billy Idol Rebel Yell Billy -

TOP HITS of the EIGHTIES by YEAR 1980’S Top 100 Tracks Page 2 of 31

1980’S Top 100 Tracks Page 1 of 31 TOP HITS OF THE EIGHTIES BY YEAR 1980’S Top 100 Tracks Page 2 of 31 1980 01 Frankie Goes To Hollywood Relax 02 Frankie Goes To Hollywood Two Tribes 03 Stevie Wonder I Just Called To Say I Love You 04 Black Box Ride On Time 05 Jennifer Rush The Power Of Love 06 Band Aid Do They Know It's Christmas? 07 Culture Club Karma Chameleon 08 Jive Bunny & The Mastermixers Swing The Mood 09 Rick Astley Never Gonna Give You Up 10 Ray Parker Jr Ghostbusters 11 Lionel Richie Hello 12 George Michael Careless Whisper 13 Kylie Minogue I Should Be So Lucky 14 Starship Nothing's Gonna Stop Us Now 15 Elaine Paige & Barbara Dickson I Know Him So Well 16 Kylie & Jason Especially For You 17 Dexy's Midnight Runners Come On Eileen 18 Billy Joel Uptown Girl 19 Sister Sledge Frankie 20 Survivor Eye Of The Tiger 21 T'Pau China In Your Hand 22 Yazz & The Plastic Population The Only Way Is Up 23 Soft Cell Tainted Love 24 The Human League Don't You Want Me 25 The Communards Don't Leave Me This Way 26 Jackie Wilson Reet Petite 27 Paul Hardcastle 19 28 Irene Cara Fame 29 Berlin Take My Breath Away 30 Madonna Into The Groove 31 The Bangles Eternal Flame 32 Renee & Renato Save Your Love 33 Black Lace Agadoo 34 Chaka Khan I Feel For You 35 Diana Ross Chain Reaction 36 Shakin' Stevens This Ole House 37 Adam & The Ants Stand And Deliver 38 UB40 Red Red Wine 1980’S Top 100 Tracks Page 3 of 31 39 Boris Gardiner I Want To Wake Up With You 40 Soul II Soul Back To Life 41 Whitney Houston Saving All My Love For You 42 Billy Ocean When The Going -

BSE 2019 Repertoire List

Boston String Ensemble Repertoire List: CLASSICAL 'Tis the Gift to be Simple (A traditional American shaker tune) Amazing Grace Bach: Air Bach: Arie “Mein glaubiges Herze” Bach: Arioso Bach: Bist du bei mir Bach: Double Concerto 2 mvt Bach: Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring Bach: My Heart Ever Faithful Bach: Prelude from English Suite No. 3 Bach: Sheep may Safely Graze Bach: Wachet Auf Bach-Gounod: Ave Maria Be Thou My Vision Beethoven: Fur Elise Beethoven: Menuett from the Septet Op. 20 Beethoven: Ode to Joy Boccherini: Menuett Brahms: Menuetto from Serenade No. 1 Bruch: Adagio from Violin Concerto No. 1 Charpentier: Te Deum Chopin: Nocturne in Eb Clarke: Trumpet Voluntary Corelli: Pastorale from Concerto Grosso Op. 6, No. 8 Debussy: The Girl with the Flaxen Hair Debussy: Le Petit Negre Delibes: Flower Duet from “Lakme” Dvorak: Humoresque Dvorak: Serenade Op. 44 Fiocco: Allegro Franck: Panis Angelicus Great Is Thy Faithfulness Gluck: Dance of the Blessed Spirits Gounod: Ave Maria Graham-Lovland: You Raise Me Up Grieg: Gavotte from Holberg Suite Op. 40 Handel: Alla Hornpipe Handel: “All We Like Sheep” from The Messiah Handel: Aria from “Xerxes” Handel: Entance of the Queen of Sheba Handel: Halleluia Chorus Handel: La Rejouissance Handel: Largo Handel: Largo from Violin Sonata in D Major Handel: March Handel: Overture from Royal Fireworks Handel: Passacaglia Handel: Water Music Handel: Where’er You Walk from “Semele” Hasse: Canzona Haydn: Serenade Hellmark: - You Deserve The Glory How Great Thou Art Irish Cradle Song Lo! How a Rose E’er Blooming Liszt: Liebestraum Mascagni: Cavalleria Rusticana “Intemezzo” Massenet: Meditation from “Thais” Mendelssohn: Canzonetta from the Quartet Op. -

Christina Aguilera Ain't That a Kick in the Head- Dean Martin Ain't

A Thousand Years- Christina Perri Building A Mystery- Sarah McLachlan Busta Move- Young MC Ain’t No Other Man- Christina Aguilera California Girls- Katy Perry Ain’t That A Kick In The Head- Dean Martin California Love- Tupac Shakur Ain’t Too Proud To Beg- Temptations Call Me Maybe- Carly Rae Jepsen All I Want Is You- U2 Car wash- Rose Royce All Night Long- Lionel Richie Celebration- Kool and the Gang All Of Me- John Legend Chain of Fools- Aretha Franklin All Right Now- Free Club Can’t Handle Me- Flo Rida All Star- Smashmouth Cold Shot- Stevie Ray Vaughn American Boy- Estelle Come Fly With Me- Frank Sinatra American Girl- Tom Petty Counting Stars- One Republic Applause- Lady Gaga Crash- Dave Matthews Band Are You Gonna Be My Girl- Jet Crazy In Love- Beyonce Are You Gonna Go My Way- Lenny Kravitz Crazy- Gnarls Barkley At Last- Etta James Dancin’ With Myself- Billy Idol Bad Bad Leroy Brown- Jim Croce Dangerous- Akon Babylon- David Gray DJ Got Us Falling In Love- Usher Bad Girls- Donna Summers Domino- Jessie J Bad Romance- Lady Gaga Don’t Know Why- Norah Jones Badfish- Sublime Don’t Stop Believing- Journey Barracuda- Heart Don’t Stop Till You Get Enough- Michael Jackson Beast Of Burden- Rolling Stones Don’t You Want Me Baby- Human League Beautiful Day- U2 Down On The Corner- CCR Before He Cheats- Carrie Underwood Dreams- Fleetwood Mac Believe- Cher Dynamite- Taio Cruz Best Day Of My Life- American Authors Empire State Of Mind- Jay-Z/Alicia Keys Big Girls Don’t Cry- Fergie Every Breath You Take- The Police Billie Jean- Michael Jackson Everything-