If Truth Be Known

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evogenesis.Pdf

EvoGenesis Easy answers to evolution The ultimate answer to evolution and the crisis in creationism John Thomas 1 2 CONTENTS PART 1 EVOGENESIS- THE REAL ORIGIN OF SPECIES 1.1 The Genesis Alternative 1.2 An Overview Of EvoGenesis PART 2 WHERE DARWIN WENT WRONG 2.1 The Darwin Delusion 2.2 Evolution Fails Fossil Test 1 2.3 Evolution Fails Fossil Test 2 2.4 Jean Baptiste Lamarck 2.5 The Origin of Variation 2.6 A Brief History of Complexity 2.7 Complexity Within Complexity 2.8 Every Body Needs a Bauplan 2.9 Neo-Darwinism 2.10 Cuvier the Catastrophist 2.11 The Self-developing Genome 2.12 Another Look at Natural Selection 2.13 The Missing Link 2.14 Faith, Assumption and Dogma 2.15 Darwin's Personal Agenda 2.16 The Birth of Geology 2.17 Rocks & Fossils 2.18 Dinosaurs and Dragons 2.19 Radiometric Dating 2.20 The Curse of Evolution PART 3 A CLOSER LOOK AT THE GENESIS ACCOUNT OF CREATION 3.1 Questions & Answers 3.2 In the Beginning 3.3 Chaos! 3.4 Day One- A Special Light 3.5 Day Two - Waters above & Waters below 3.6 Day Three - The Dry Land, the Sea & Plants 3.7 Day Four - The Sun, the Moon & Stars 3.8 Day Five- Fish & Birds 3.9 Day Six - Cattle, Creeping Things and Beasts 3.10 Day Six - Man 3.11 Day Six- Everything was Good 3.12 Eden 3.13 The Flood of Noah - Some Questions 3.14 The Ark 3.15 The Deluge 3.16 The Aftermath Conclusions 3 4 PREFACE HISTORY REPEATING History, we are told, has a habit of repeating itself. -

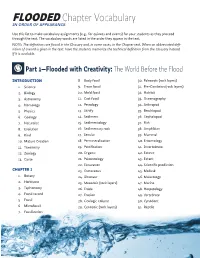

Chapter Vocabulary in ORDER of APPEARANCE

FLOODED Chapter Vocabulary IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE Use this list to make vocabulary assignments (e.g., for quizzes and exams) for your students as they proceed through the text. The vocabulary words are listed in the order they appear in the text. NOTE: The definitions are found in the Glossary and, in some cases, in the Chapter text. When an abbreviated defi- nition of a word is given in the text, have the students memorize the technical definition from the Glossary instead, if it is available. FLOODED WITH Part 1 CREATIVITY The World Before the Flood Part 1—Flooded with Creativity: The World Before the Flood INTRODUCTION 8. Body fossil 30. Paleozoic (rock layers) 1. Science 9. Trace fossil 31. Pre-Cambrian (rock layers) 2. Biology 10. Mold fossil 32. Habitat 3. Astronomy 11. Cast fossil 33. Oceanography 4. Nomology 12. Petrology 34. Arthropod 5. Physics 13. Lithify 35. Brachiopod 6. Geology 14. Sediment 36. Cephalopod 7. Naturalist 15. Sedimentology 37. Fish 8. Evolution 16. Sedimentary rock 38. Amphibian 9. Kind 17. Secular 39. Mammal 10. Mature Creation 18. Permineralization 40. Entomology 11. Taxonomy 19. Petrification 41. Invertebrate 12. Zoology 20. Organic 42. Extinct 13. Curse 21. Paleontology 43. Extant 22. Excavation 44. Scientific prediction CHAPTER 1 23. Cretaceous 45. Mollusk 1. Botany 24. Dinosaur 46. Malacology 2. Herbivore 25. Mesozoic (rock layers) 47. Marine 3. Taphonomy 26. Erode 48. Herpetology 4. Fossil record 27. Erosion 49. Vertebrate 5. Fossil 28. Geologic column 50. Cynodont 6. Microfossil 29. Cenozoic (rock layers) 51. Reptile 7. Fossilization 52. Ornithischian 85. Gymnosperm 20. -

Critical Analysis of Article "21 Reasons to Believe the Earth Is Young" by Jeff Miller

1 Critical analysis of article "21 Reasons to Believe the Earth is Young" by Jeff Miller Lorence G. Collins [email protected] Ken Woglemuth [email protected] January 7, 2019 Introduction The article by Dr. Jeff Miller can be accessed at the following link: http://apologeticspress.org/APContent.aspx?category=9&article=5641 and is an article published by Apologetic Press, v. 39, n.1, 2018. The problems start with the Article In Brief in the boxed paragraph, and with the very first sentence. The Bible does not give an age of the Earth of 6,000 to 10,000 years, or even imply − this is added to Scripture by Dr. Miller and other young-Earth creationists. R. C. Sproul was one of evangelicalism's outstanding theologians, and he stated point blank at the Legionier Conference panel discussion that he does not know how old the Earth is, and the Bible does not inform us. When there has been some apparent conflict, either the theologians or the scientists are wrong, because God is the Author of the Bible and His handiwork is in general revelation. In the days of Copernicus and Galileo, the theologians were wrong. Today we do not know of anyone who believes that the Earth is the center of the universe. 2 The last sentence of this "Article In Brief" is boldly false. There is almost no credible evidence from paleontology, geology, astrophysics, or geophysics that refutes deep time. Dr. Miller states: "The age of the Earth, according to naturalists and old- Earth advocates, is 4.5 billion years. -

Apologetic Resources

APOLOGETIC RESOURCES A Young Earth ministry perspective, namely contrasting Scripture to true science now and during the ages. By Dr. Jim Pagels [email protected] 9/2016 Editor Dr. John Fricke, Emeritus Professor of Biology, Concordia University, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Copyright This book is offered as an educational resource on a no cost basis. Contents are not to be reproduced for the purpose of sale. Note that all Scriptural passages are taken from the English Standard Version. 1 I HAVE NO GREATER JOY THAN TO HEAR THAT MY CHILDREN WALK IN THE TRUTH III JOHN 1:4 Forward - Although there is much young Earth information available from commercial sources and on the internet, it was the impression of this writer that no resource that deals with basic topical issues correlating the young Earth philosophy and science exists for professional church workers. To this end, Apologetic Resources is being offered. Intended Audience – The intended audience of this reference material is primarily use by professional church workers, i.e., teachers, pastors, youth workers, etc., namely those who choose to uphold the literal interpretation of Genesis and the inerrancy of Holy Scripture. The focus in this regard is Young Earth Creationism and the catastrophic nature of the global Genesis Flood keeping in mind that Genesis 1-11 is foundational to most of the significant doctrines of Holy Scripture. Of course, laymen may well also find this reference a valuable resource. There is obviously a realistic interplay between Scripture, apologetics and true science. The goal of this document is to provide clarity to this interaction. -

Download January 2020

INSTITUTE FOR CREATION RESEARCH ICR.org JANUARY 2020 ACTSVOL. 49 NO. 1 FACTS & Homo naledi : Another Failed Evolutionary Ape-Man page 10 The Plan to Replace God page 14 Survival of the Fittest and Evolution’s Death Culture page 17 Do Earth’s Rocks Look Old? page 20 2020 - 50 CreationYears1970 Research of $24.99 BHMMFOMC HENRY M. MORRIS Hardcover Dr. Henry M. Morris, founder of the Institute for Creation Research, spent a lifetime investigating scientific evidence that confirms the Bible. In Henry M. Morris: Father of Modern Creationism, you’ll see how God used this humble man to boldly proclaim the veracity of His Word. Dr. Morris’ work rebuilt Christians’ confidence in the accu- racy of the Bible and turned many toward Christ for the first time. LITTLE CREATION BOOKS You and Me Space Noah’s Ark 6 Days of Dinosaurs Fish Have Always $5.99 • BYAMBB $5.99 • BSBB $5.99 • BNABB Creation $5.99 • BDBB Been Fish $5.99 • B6DOCBB $5.99 • BFHABFBB SCIENCE FOR KIDS $24.99 Buy the whole set and save $10! $35.96 God Made Gorillas, PSFK4 God Made You Dinosaurs: God’s Mysterious Creatures $7.99 Space: God’s Majestic Handiwork BGMGGMY Animals by Design: Exploring Unique Creature Features Earth: Our Created Home $8.99 $8.99 BDGMC BSGMH Big Plans for Henry A Little Book with a Big Plan Henry Plush Toy $8.99 $8.99 $8.99 • BBPFH $12.99 • GHTH BABDEUCF BEOCH Buy both for $15.99 • PBPFH Call 800.628.7640 or visit ICR.org/store | Please add shipping and handling to all orders. -

Contentious Fossils Cies As the Result of Degradation And/Or a Review of Cross-Breeding.1 Bone of Contention: Is Evolution True? 2

Book Reviews Contentious fossils cies as the result of degradation and/or A review of cross-breeding.1 Bone of Contention: Is Evolution True? 2. Just what do the fossils Third edition prove? by Sylvia Baker Published by Biblical Crea- The three evolution-inspired ex- tion Society, UK. 2003 pectations of the fossil record, listed in the previous edition, have now been reduced to just two. The following Philip Bell statement has been dropped: ‘c. We should, of course, expect to This new-look edition of a popular find the rock strata themselves in and helpful booklet is described as the order given by the geological containing new material throughout column, with the oldest at or near the bottom, and the most recent at its pages. With the exception of one 2 illustration of corals, which appeared the top.’ on page 31 of the previous edition Perhaps this is to diffuse espoused by Steven Robinson in a potential criticism that creationist 3 (published by AiG), all the illustrations symposium in this Journal in 1996, but arguments about ‘out-of-place’ fossils from that edition are reproduced here, which (in my view) has been soundly represent a ‘straw man’ perspective of 4 and mostly in the same place in the text, refuted since, again in this journal. To the rocks, not held by paleontologists. giving the superficial appearance that be fair, Baker does not insist that the Alternatively, it could represent an very little has changed. word—machah in the Hebrew—must acknowledgement that the stratigraphic However, there are indeed a mean ‘blot out, without trace’. -

Chapter 3: the Age of the Earth, the Fossil Record and Noah's Flood

Chapter 3: The age of the earth, the fossil record and Noah’s flood. A week later, Xiao Wang and Xiao Li returned to Professor Ho‘s office, arguing heatedly as they entered. ―Good afternoon boys!‖ Professor Ho greeted them happily, standing up behind his desk, which was strewn with books as always. ―What is it you‘re discussing?‖ Xiao Wang nodded in greeting and launched in: ―Professor Ho, I‘ve been researching what you‘ve discussed with us. I have to admit, I‘m something of an ‗intelligent design‘ theorist now. But I still have a big problem with your Bible cr- eationism. Scientists have found fossils in rock layers which show evolution happened for millions of years—‖ Xiao Li cut in: ―I already told him, Professor Ho, that that just means God used evolution! Evolution is God‘s tool- box.‖ Xiao Wang shook his head. ―That‘s ridiculous! I‘ve read the book of Genesis and it doesn‘t look in the least bit like evolution. The fossil record of evolution is a long, bloody process of struggle, death and change. If there was evolution, you don‘t need a God as a Creator!‖ ―You‘d still need a Creator!‖ countered Xiao Li. ―Life didn‘t start by itself, and animals wouldn‘t change into new forms by themselves by accident. Professor Ho proved that to us already. You still need God to drive evolution for- ward.‖ ―If there‘s a ‗god,‘ behind evolution, then he‘s sloppy and cruel. The fossil record looks nothing like the story of the Garden of Eden!‖ Xiao Li forced a look of patient wisdom onto his face. -

From the Joggins Formation, Cumberland Basin, Nova Scotia

The Age of the Earth The Age of the Earth • Present Christ 2,000 years • Christ Abraham 2,000 years • Abraham Adam ? Genesis 5, 11 Adam 130 Seth 105 Enosh 90 Kenan 70 Mahalalel 65 Jared 162 Enoch 65 Methuselah 187 Lamech 182 Noah 500 Shem 100 Arpachshad 35 Shelah 30 Eber 34 Peleg 30 Reu 32 Serug 30 Nahor 29 Terah 70 Abram 1946 The Age of the Earth • Present Christ 2,000 years • Christ Abraham 2,000 years • Abraham Adam 2,000 years 6,000 years Allowing wiggle room: 6,000–12,000 years Polystrate fossils Polystrate fossil (tree with roots) From the Joggins Formation, Cumberland Basin, Nova Scotia. Rygel, M.C. Polystrate fossils “There is no doubt that this type of fossil was formed relatively quickly; otherwise it would have decomposed while waiting for strata to slowly accumulate around it” (Scott Huse, The Collapse of Evolution). Circular reasoning in the geologic column Didier Descouens Circular reasoning in the geologic column • Niles Eldredge: “Paleontologists cannot operate this way. There is no way simply to look at a fossil and say how old it is unless you know the age of the rocks it comes from…And this poses something of a problem: if we date the rocks by their fossils, how can we then turn around and talk about patterns of evolutionary change through time in the fossil record?” (Time Frames, 1985). Circular reasoning in the geologic column • Thomas S. Kemp: “A circular argument arises: Interpret the fossil record in the terms of a particular theory of evolution, inspect the interpretation, and note that it confirms the theory. -

Creation V. Evolution

CREATION V. EVOLUTION: WHat THEY won’T TELL YOU IN BioloGY ClaSS What Christians Should Know About Biblical Creation Daniel A. Biddle, Ph.D. (editor) Copyright © 2014 by Genesis Apologetics, Inc. E-mail: [email protected] Genesis Apologetics, Inc. P.O. Box 1326 Folsom, CA 95763-1326 CREATION V. EVOLUTION: What They Won’t Tell You in Biology Class What Christians Should Know About Biblical Creation by Daniel A. Biddle, Ph.D. (editor) Printed in the United States of America ISBN 9781628717761 All rights reserved solely by the author. The author guarantees all contents are original and do not infringe upon the legal rights of any other person or work. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the permission of the author. The views expressed in this book are not necessarily those of the publisher. Unless otherwise indicated, Bible quotations are taken from the HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved. The “NIV” and “New International Version” trademarks are reg- istered in the United States Patent and Trademark Office by the International Bible Society. Use of either trademark requires the permission of the International Bible Society. www.xulonpress.com Dedication o my wife, Jenny, who supports me in this work. To my children Makaela, Alyssa, Matthew, and Amanda, and Tto your children and your children’s children for a hundred generations—this book is for all of you. To Dave Bisbee and Mark Johnston, who planted the seeds and the passion for this work. -

Debunking Evolution: What Every Christian Student Should Know

DEBUNKING EVOLUTION: WHAT EVERY CHRISTIAN STUDENT SHOULD KNOW A Six-lesson Video-based Training Program for Christian Students Daniel A. Biddle, Ph.D. (editor) Copyright © 2016 by Genesis Apologetics, Inc. E-mail: [email protected] http://www.genesisapologetics.com: A 501(c)(3) ministry equipping youth pastors, parents, and students with Biblical answers for evolutionary teaching in public schools. DEBUNKING EVOLUTION: WHAT EVERY CHRISTIAN STUDENT SHOULD KNOW A Six-lesson Video-based Training Program for Christian Students by Daniel A. Biddle, Ph.D. (editor) Printed in the United States of America ISBN-13: 978-1533064387 ISBN-10: 1533064385 Unless otherwise indicated, Bible quotations are taken from the HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved. The “NIV” and “New International Version” trademarks are registered in the United States Patent and Trademark Office by the International Bible Society. Use of either trademark requires the permission of the International Bible Society. Dedication To my wife, Jenny, who supports me in this work. To my children Makaela, Alyssa, Matthew, and Amanda, and to your children and your children’s children for a hundred generations—this book is for all of you. To Dave Bisbee and Mark Johnston, who planted the seeds and the passion for this work. We would like to acknowledge Answers in Genesis (www.answersingenesis.org), the Institute for Creation Research (www.icr.org), and Creation Ministries International (www.creation.com). Much of the content herein has been drawn from (and is meant to be in alignment with) these Biblical Creation ministries. -

Fossil Evidence Evaluated

Fossil Evidence Evaluated By Robert S. Westcott • We have discussed the mechanics of genetics and the specificity of producing the dictated organisms from the basic 20 amino acids. These amino acids are placed in the exact position to comprise the puzzle pieces that become puzzle pieces to successively larger picture puzzles until the whole organism is completed according to its specific kind. Our master molecule, DNA, determines exactly which organism will be produced, and the process continues from life to life with very few variations in the exact genetic instructions. • Now we will turn to an inspection of fossil evidences of past life and objectively evaluate whether the history of organisms preserved as fossils supports the evolutionist claims. • How did life first come into being? • Do the records of fossils actually support the theory of organic evolution? • What are the limitations to the production of new forms of life? • If so, how far does the mechanism of evolution extend in producing the variations that we see in fossils and in living plants and animals? You see this argument in the teachings of evolutionists. • “Fossil remains begin to prove beyond doubt that organisms had lived on the Earth much earlier than the believers in special creation had thought. Furthermore, the fossil records revealed a wonderfully consistent trend: in general, the older the fossils, the simpler they tended to be in structure. The complex forms tended to be more recent in origin.” • • “This discovery pointed to a process of gradual development of complexity. For example, when geologists examined the sides of a gorge, such as the Grand Canyon, they found fossils of complex plants and animals only near the top.” • “As they examined fossils at greater depth in the gorge, the fossils were of simpler types. -

Polystrate Trees: Flood Burial Or Not?

Polystrate Trees: Flood Burial or Not? Polystrate Tree Question Polystrate trees are fossilised trees or parts of trees that pass through many layers of rock, i.e. poly – many, strata – layers. For many years Creation Research has presented these as evidence for rapid catastrophic formation of fossils and rock layers. In response to this, we recently received the following question: I have recently returned from New Guinea were I have seen trees being buried where they grew, by silica rich springs in a volcanic zone. Surely if this is happening while we watch, then this is a good explanation of polystrate trees rather than rapid catastrophic flooding? Can you explain? John Mackay has studied polystrate trees in many locations around the world. Below is his answer, with real examples from actual field geological research. Mineral Spring Preservation I have seen many trees in rich mineral spring areas that are being buried where they grow, but they are readily distinguishable from the far more widespread polystrate fossil trees and here’s how. Since they are growing on the spot, and being buried on the spot, their whole environment is being buried from the roots up. So, whenever you excavate any such tree fossilised in this manner, then any soil, roots, the base of the tree, surrounding grasses, any fallen leaves from the tree (or nearby trees) are also entombed, and while the tree remains alive you get a blow by blow preserved environmental record as the fossil tree forms. Check out my pictures of mineral spring fossilised trees, and note their features.